That Bill Haywood, born in 1869 to a hardscrabble existence of white settlers in s still contested West, grew up to become a tough and imposing man is not surprising. That this giant of a hard rock miner became a deeply empathetic and kind, indomitable warrior for all of the oppressed, is. One of the great figures of the U.S. and international workers’ movement, Haywood’s life story complicates many of the myths and realities of American history. Serialized in the Daily Worker in what would become the remarkable first chapter of his autobiography, Haywood describes his first 15 years of life in Salt Lake City, Utah where criminal speculation, religious hypocrisy, violent dispossessions, and racist lynchings were de rigueur. These memoirs finished in Haywood’s Moscow exile, a sort of Socialist Western and an extraordinary read.

‘Boyhood Among the Mormons’ by William D. Haywood from the Daily Worker. Vol. 5 Nos. 315-318. January 5-9, 1929.

My father was of an old American family, so American that if traced back it would probably run to the Puritan bigots or the cavalier pirates. Neither case would give me reason for pride. He was born near Columbus, Ohio, and with his parents migrated to Iowa, where they lived at Fairfield. His brother and cousins were soldiers in the Civil War; all of them were killed or wounded. My father, when a boy, made his way across the prairies to the West. He was a pony express rider. There was no railroad across the country then and letters were carried by the Pony Express, which ran in relays, the riders going at full speed from camp to camp across the prairies, desert and mountains from St. Jo, Missouri, to San Francisco on the Pacific coast.

My mother, of Scotch-Irish parentage, was born in South Africa. She embarked with her family at Cape of Good Hope for the shores of America. They had disposed of everything, pulled up by the roots, and left her birthplace to make their way to California. The gold excitement had reached the furthest corners of the earth. People without the slightest knowledge of what they would have to contend with were leaving for the West. There were no palatial steamships in those days; it meant months of dreary, dangerous voyage in a sailing vessel. The danger was not past when they landed in port; there was still the train ride of eighteen hundred miles, and then the long trip across the plains and mountains in covered wagons drawn by oxen. There was the constant dread of accident, of sickness, and of the hostile Indians, red men who had been forced in self-protection to resent the encroachment of the whites.

On the way across the prairies, my uncle, then a small boy, was lost. The family did not know what had become of him. They searched the long wagon-train in vain. He was in none of the prairie schooners, he was not among the stock drivers who drove the extra oxen, cows and mules. The train could not stop and one family could not drop behind alone to search the boundless prairies. They gave him up for lost and went on with the wagon train, grieving for him. When they pulled down Emigrant Canyon, they saw the beautiful Salt Lake Valley. The dead sea, Great Salt Lake, spread out in front of them. To the right lay the new city of Zion, which had been founded by the Mormons in 1847. Here the family abandoned the wagon-train because of sickness and had to wait for the train following with the hope that my uncle had been picked up and brought along. It was but a few days after their arrival that my grandmother, walking along the street, saw her son with a basket of apples on his arm. She gathered him up, apples and all, and took him home to his sisters. He had gone with the train ahead and had reached the city a week or two earlier.

My grandmother started a boarding house in Salt Lake City. My father boarded there and met my mother. He was then a very young man; when they married, he was about twenty-two and my mother was a girl of fifteen. I was born on the fourth of February, 1869, before a railroad spanned the continent.

I have but one remembrance of my father. It was on my third birthday. He took me from the house and set me up on a high board fence, which he climbed over, lifting me down on the other side. We went through an alley-way to Main Street, then to a store where he bought me a new velvet suit, my first pants. We called on many of his friends on the way home, and I was loaded with money, oranges and candy. My father died shortly afterward at a place called Camp Floyd, now known as Mercur. When my mother learned of his illness she started for Camp Floyd, taking me with her, but before her arrival he had died of pneumonia and was buried. When we visited his grave, I remember digging down as far as my arm could reach.

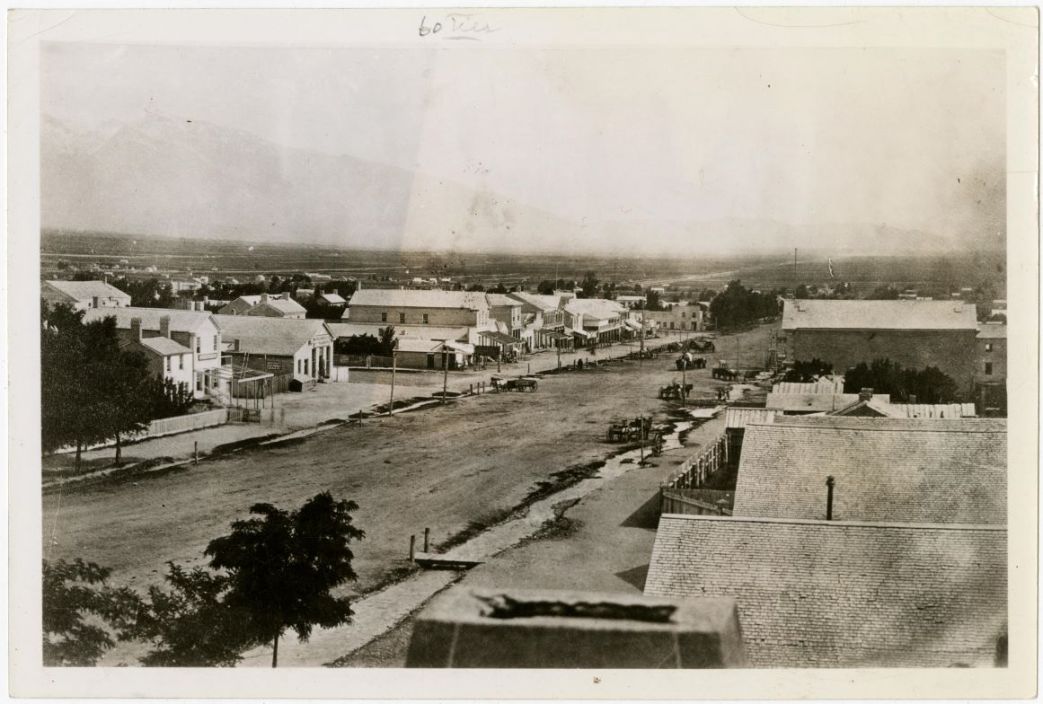

Salt Lake City is built in a bend of the Wasatch range. To the east the mountains rise high and stark, to the north is Ensign Peak, near the top of which is a tiny cave that has been explored by all the adventurous youngsters of the town. To the southwest, in the Oquirrh Mountains, lies much of the wealth of Utah. Here are the mining camps of Stockton, Ophir, Mercur, and Bingham Canyon, where is the great Utah copper mine. To the immediate west is the Great Salt Lake, whose waters are so dense with salt that no animal life can survive.

On the islands in the Salt Lake are nests of thousands of seagulls, which are sacred in Utah because of the fact that during a plague of grasshoppers the gulls fed upon the pests, eating millions. They would swallow as many grasshoppers as they could hold, then spew them up and swallow more, and in this way the sea-gulls helped to save a part of the farmers’ crop, the total loss of which would have meant starvation for the Mormons.

Salt Lake valley is threaded by the Jordan River, and to the north are warm and hot springs. The grandeur of the scenery and the beauty of the city itself were counteracted by the bad feeling generated by the Mormon Church. Especially was this true during my boyhood days, when the atmosphere was still charged with the Mountain Meadow Massacre, the destruction of the Aiken party, and the threats of the Mormons against the Apostates. These threats were thundered from the lips of Brigham Young, Hyde, Pratt, and other church officials. Of course, they did not make the impression on me that they did on older people, though I remember distinctly some of the features of the trial of John D. Lee, who was a leader of the Mormons and Indians who killed nearly a hundred and fifty men, women and children at Mountain Meadow. The massacre occurred after Lee had got the emigrants to surrender their arms. Lee himself and other Mormons had a bitter hatred against these particular emigrants, who were from Arkansas and Missouri, where the so-called Mormon prophet, Joseph Smith, and his brother Hyrum had been murdered in the jail at Carthage, Missouri. I remember seeing a picture of John D. Lee sitting upon his coffin before he was executed at Mountain Meadow. The laws of Utah Territory provided that when a man was sentenced he could take his choice of the means of execution, either shooting or hanging. John D. Lee chose shooting, and was taken from the county seat where he was tried, to Mountain Meadow, the scene of his crime, which undoubtedly had been instigated by others higher in authority. But twenty years passed by between the massacre and the execution in 1877.

It was at about this time that I first saw Brigham Young, the president of the Mormon Church, on the street, although I had seen him before in the Tabernacle, and had heard him deliver his vigorous sermons against apostacy. A short time later he died, supposedly from eating green corn; but rumors were current that he had poisoned himself. If these rumors were true, it was probably because of John D. Lee’s conviction and the demand on the part of the Gentiles, as all non-Mormons were called, for the arrest and trial of Brigham Young in connection with the massacre, at the time of which he had been governor of the Territory, and United States Indian Agent The Mormons had sensibly cultivated friendly relations with the Indians, and they undoubtedly prevented the massacre of another party of emigrants who came through at about the same time.

The house where I was born was built of adobe, on First South Street, between West Temple and First West. It was divided into four apartments, two on the ground floor and two above. The interesting feature of this house was the family who lived above us, a woman who had been a widow with two grown daughters. At the time of which I write they were all married to the same man, so that the daughters were wives of their own stepfather. Polygamy has always been a religious tenet of the Mormon Church.

Some four years after the death of my father, my mother remarried, and we went to a mining camp called Ophir, to live. Ophir Canyon was steep. On the right the mountains were precipitous, broken with gulches. On the left were lower hills. The canyon widened where the town was built, giving room enough for two or three streets. Lion hill was at the head of the canyon. Over the mountain back of our house was Dry Canyon, where the Hidden Treasure mine was located. At this and other mines of the camp my stepfather worked. The ridge near the Hidden Treasure was strewn with great bowlders of copper pyrites. The Miners’ Delight mine was a tunnel with some open works which were the playground of the boys of the camp. There we found many beautiful crystals which we loved to collect.

Mrs. Whitehead was my first teacher. The schoolhouse at Ophir was built at the upper end of the town and was little more than a lumber shack. From the windows in the late winter we could see the snow slides coming down the mountain side from which all the timber had been cut. The first winter a slide filled the canyon below the town, through which a tunnel had to be cut for the stage to come through, and to let the water out. At the noon recess Mrs. Whitehead would appoint a monitor who would report to her how we behaved in her absence. One day Johnnie O’Neill and I were reported for fighting, and when school was called to order, he was called up and given a whipping with the ruler. I ran pell-mell for the door and home, where I told my mother that I was not going to school any more because the teacher was going to whip me for fighting, and there hadn’t been any fight. That night my mother took me to Mrs. Whitehead’s house and I told them I guessed I knew when I was fighting and when we were wrestling. The matter was patched up and I went back to school the next day. However, Johnnie O’Neill and I had many a fight, both before and after this wrestling match.

One morning I was going to school, which was only a short distance from our house, when I saw Mannie Mills across the street pull his gun from his pocket and shoot at Slippery Dick, who was walking just ahead of me. Dick also began shooting and they exchanged several shots when Mills fell on his face, dead. Several people ran up to him. Slippery Dick blew into the barrel of his sixshooter, put it in his pocket and walked away. I followed him until he went into a nearby saloon. That was the first time I saw a shooting scrape. It was not the only one that occurred in Ophir, which was regarded as one of the wildest mining camps in the West. Another day I went to the scene of a shooting scrape and saw two members of the Turpin family and another man lying dead on the ground.

There was an explosion one night under a corner of Duke’s hotel. The next morning I was in front of Lawrence’s store when a woman, called “Old Mother” Bennet, came walking down the street muttering something about “burning down the town.” A man who was sitting on the edge of the sidewalk jumped to his feet and struck her in the face. It was Johnny Duke, the owner of the hotel. This woman and her man had bragged about planting the powder, and after the incident on the sidewalk both were arrested and the Vigilance Committee drove them down the canyon that very afternoon.

Another day two schoolmates of mine were playing in the livery barn. They were in the room where the hostler slept and found a pistol under the pillow. Accidentally, Pete Bethel pulled the trigger and killed Willie Duke. When I heard the shot I ran to the stable and found Willie dead. I saw the blood running out of his head. Little Pete Bethel was scared speechless.

These scenes of blood and violence happened when I was seven years old. After the talk of massacres and killings at Salt Lake City, I accepted it all as a natural part of life.

It was an event when the Dutch shoemaker’s family arrived in the camp. A day or two after their arrival I was playing down by the creek near the shoemaker’s house when I saw a little girl in the shadow of a clump of willows. Going over to her, I found that she was very pretty, with cheeks like big red apples. When I spoke to her she only smiled. I took her hand, then I kissed her and she seemed to like that. Some one called, her mother, I guessed. Breaking away from me she ran to the house, smiling back at me over her shoulder. The next day I went back and there she was, dipping up a bucket of water from the creek. I went up quietly and put my arms around her, when she turned and scratched my face, spat at me and lifted the bucket as though to throw the water over me. I ran away, not knowing what had come over her. Later I found that it was not she at all; it was her twin sister.

Most of the boys in the camp had slingshots. I was going to make one for myself. I was back of the house trying to cut a handle from a scrub-oak, when the knife slipped and penetrated my eye. They sent me to Salt Lake immediately for medical attention, and for months I was kept in a dark room. But the sight was gone.

When I returned to Ophir, school was closed and I did my first work in a mine. I was then a little past nine years of age. It was with my stepfather, who was doing the assessment work at the Russian mine.

School opened again, and I went another term. This time Professor Foster was the teacher, a stern-looking old Mormon from Tooele, but an excellent teacher. He taught me to understand history, to dig under and back of what was written. He was a lanternjawed, gray-mustached old man with gray eyes, and I never saw him whip a child.

Hardly a week passed without a fight with some boy or other, who would call me “Squint-eye” or “Dick Dead-eye,” because of my blind eye. I used to like to fight.

After this term of school the family returned to Salt Lake City. Zion, as the Mormons called the city, was intended originally as the capital of an empire of the Mormon Church. When gold was discovered in California, the emigrants swarmed through Utah on their way to the gold fields of the West. Some dropped off at Salt Lake City and stayed, but curiously enough, in spite of the stampede for gold, no Mormons joined in the rush or left their territory.

The Temple Block, where the Tabernacle, the Assembly Hall, the Endowment Houses and the Temple were enclosed within high walls, was the heart of the city; around it everything centered. In the Tabernacle, where eight thousand people could gather, I heard Adelina Patti sing one night when I was a young boy. I have never forgotten it.

The city was built with wide streets that were numbered from the Temple Block. Along the gutters ran streams of mountain water which was used to water the gardens with which every house was surrounded.

The population was divided. Mormons were the dominant factor. The others, even the Jews, were known as Gentiles. The Mormons controlled most of the business and all of the farms. Many of the larger enterprises, factories and farms, were owned by the church, which maintained tithing offices, a newspaper and an historian’s office. The Gentiles of the Territory were miners, business men, saloon keepers, lawyers and politicians. The Deseret News was the official paper of the Mormons, while the Salt Lake Tribune spoke for the Gentiles. Against the Gentiles there was a bitter antipathy, as the older Mormons could not forget the outrages they had suffered, their property that had been destroyed, the killing of their leaders, their final abandonment of the states where they had lived, and their search for a new home where they could be safe from persecution, and which was now being invaded by their old-time enemies. That spirit of bitterness has somewhat died down with the newer generation, but when I was a boy it was at its height.

We lived for years near the house that was my birthplace, in different rented houses, always surrounded by polygamous families; the Taylors, the Evanses, the Cannons. John Taylor, one time president of the Church of Latter Day Saints, as the Mormons call their church, lived across the street from us. He had eight wives in one half block. Next door to our house was one of several families of William Taylor, a brother of the president, and the first house from theirs was the home of Porter Rockwell. He had the reputation of being a Danite, or one of the Destroying Angels, an associate of the notorious Bill Hickman. Concerning these Destroying Angels, it was said that their function was to avenge the church by doing away with such offenders as apostates. Rockwell was a mysterious being to the boys of the neighborhood, most of whom were Mormons. All had heard of the terrible things that he and Hickman were accused of, through rumors and whispers in their families. There was nothing definite, but enough to arouse the curiosity of the youngsters so that when we saw Porter Rockwell on the street, with his long gray beard, gray shawl, gray slouch hat, and iron gray hair falling over his shoulders, we would run along in front of him, staring back at his not unkindly face. After Porter Rockwell died, some boys in the neighborhood thought it would be a good joke to haunt the big house where he had lived alone. One who worked in a drug store got some phosphorus, which we put on a sheet. We tied the sheet to a rope, and pulled it from the house to the barn. Breaking into the house, we rattled pieces of iron and crockery in an old keg, shook the windows and did other things to make a noise, so that one passing could not fail to notice the disturbance. The ghostly sheet and the continuous racket on dark nights gave the house the reputation of being haunted. All the boys who belonged to the gang were initiated with different hair-raising stunts.

The Sisters’ Academy of the Sacred Heart was in the next block. They had a little building adjoining the girls’ school where some small boys from the adjacent mining camps were boarded and given their first education. There were some day-scholars. Though not a Catholic, I was admitted to the school, where a nun called Sister Sylva was our teacher.

During vacation time my uncle Richard came to visit us from one of the near-by mining camps. Reading an advertisement one day in the paper that a boy was wanted on a farm, he talked it over with my mother, with the result that I was bound out to John Holden. For a period of six months at one dollar a month and board I was to be boy-of-all-work on the farm. There I milked two cows, fed the calves, cleaned out the stable, but my main job was driving a yoke of oxen.

One day I was in the field harrowing while Holden was plowing. A tooth of the harrow turned up a nest of field mice. They were curious little things. I had never seen the like before, and got down on my knees to examine them more closely. They were red, with no hair on their bodies. Their eyes were closed. The nest was a neat little home all lined with what seemed to be wool. It seemed only a few minutes that I looked at them, when all of a sudden I felt a smarting whip-lash across my body. Holden had crossed the field, picked up the bull-whip I had dropped, and struck me without saying a word. I jumped up and ran straight to the house, gathered up my few belongings, tied them into a bundle and started for home. As I crossed the fields some distance from Holden I sang out: “Good-by, John!” I walked to the city some ten miles distant. This was my first strike.

When I got home and told my mother that I had quit, because Holden had struck me with the whip, she was angry at the abuse, but was afraid of what he might do on account of the paper that she had signed, which was an indenture binding me to work for him. Holden came to our house the next day, my mother scolded him for daring to strike me with a whip. He admitted to having a bad temper and promised never to do it again, so I went back with him and served my time. Holden was a cruel man, cruel to his horses, cruel to his oxen, cruel to his wife, who often used to say that “it would be better to be an old man’s darling than a young man’s slave.”

My next job was working for Mrs. Paxton, who had a small store. I ran errands and chopped kindling wood which she sold in packages. Her son, Clem Horseley, was chief usher in the Salt Lake Theater, and he added a little to the small wage of a dollar and a half a week that I was getting from his mother by giving me a job as an usher at fifty cents a night when there were shows at the theater. Besides showing people to their seats, we also acted as claquers, starting or increasing the applause at the end of each act. This job gave me an opportunity to see many plays that I should otherwise have missed. I became interested in the plays and tragedies of Shakespeare, as Booth and Barrett appeared in Salt Lake City while I was working in the theater. I later became an ardent reader of Shakespeare. All sorts of shows were given at this theater; I saw everything from home talent to the stars that stopped over on their way to the coast. There were opera companies, oriental jugglers, and boxing exhibitions given here, although the theater was the property of the Mormon Church.

Then I got a job with old John C. Cutler. He was a good man to work for. His store was a fruit commission house. He was a fine, red-cheeked old man with a white beard, good-tempered and genial, who had many old cronies who visited him in the store. I once heard them discussing their different marital relations. Old man Cutler had two wives. The older one, the mother of four prominent Mormons of Utah, lived in Salt Lake City, the younger one in South Cottonwood. He remarked that he had yet another wife, a buxom lass who had a fine baby, but he added: “I don’t know where she is now.” Why he laughed when he said this, I never did understand. This old man would occasionally get stuck with consignments of grapes, bananas or other perishable fruit. He would turn these in to the tithing office of the church, where I would deliver them. Once in a while he would say to me, “William, do you think you can sell that fruit?” Once he sold me ten or twelve bunches of bananas at twenty-five cents a bunch, which I quickly disposed of at a dollar and a half a bunch; another time it was tomatoes at twenty-five cents a bushel; of these my mother and other women in the neighborhood made ketchup.

I used to go swimming with Joe and Heber Cutler in the Jordan River. I was caught with a cramp once and would have drowned if Joe had not come to my aid. I tried to repay this one night, when a warehouse back of John Cutler’s store caught fire. I knew the boys were sleeping in the store, and a rumor was going through the crowd that there was powder in the warehouse. I ran up the street to rout them out, when I heard the explosion. The broken glass dropped out of the windows of the stores like a waterfall, but I got through uninjured. The Cutler boys had been awakened and had already escaped from the store, and the fire was soon extinguished.

When I was about twelve I ran a fruit stand on Elephant Corner for old man Reese. Around dinner time one day I heard some shooting down the street and saw a crowd gathering in front of Griggs’ restaurant. I ran down to see what the trouble was. Two policemen were bringing a Negro out of the restaurant. From what the crowd said I understood that he had killed one policeman and the watermaster, and had wounded another policeman.

The policemen, with the crowd following, started toward Second South Street. I wondered why they did not go the shortest way to the jail; the route they took was nearly a block longer. As they went along Second South Street, a grocer left his store and joined the crowd, folding up his apron and tucking it into his belt as he walked along. This man, whose name I did not know, shouted: “Get a rope!” I thought to myself, “What do they want with a rope? The police have got him fast.”

The crowd was increasing and getting more excited at every step. The added distance increased the number of the mob. As the jail was reached, I could see the prisoner and the policemen on the steps that led up to the door. It seemed to me that the policemen, instead of pushing the Negro into the prison, pushed him into the hands of the mob. I did not see him again until I had crowded in under the arms of the mob, which was then standing hushed as though stricken with awe. Then I saw the Negro hanging by the neck in the wagon shed. His face was ghastly, and although he was light colored, it was turning blue, with the eyes and tongue sticking out horribly. I looked at the swinging figure and thought over and over, “What have they done — what have they done — ” It was as though a weight of cold lead settled in my stomach.

The leaders of the mob were not satisfied with the death of the man. Some one cried out: “Drag him out and quarter him! Hang him to a telegraph pole!” They dragged the limp body by the neck to the corner of the street, where Mayor Wells drove up and read the riot act, ordering them to return the body at once to the jail. This was my first realization of what the insane cruelty of a mob could mean. I learned then, too, that the mob was not composed only of those who would be willing themselves to do the dreadful deed that was done, but many were there out of curiosity to see what was going to be done. Each one there lent the strength of his presence to the leaders. I don’t think more than three or four men there really wanted to kill that man.

A messenger boy has the opportunity to see things and know people intimately, and working as a messenger boy I had this chance. It put me in touch with all the leading citizens of Salt Lake City. People were not guarded in what they said before a young boy, and I heard their business plans, their scandals and their political schemes. In this way I came to know of the plans that were being matured against the Mormons, which finally resulted in the passage of the Edmunds Act, which forbade polygamy. In opposition to this plan, a scheme was framed up by the Mormons, who employed a woman and brought her to the city, established her in a house which was supplied with convenient peep-holes, and invitations were sent out to prominent Gentiles to visit the lady, who had with her some interesting young friends. Through a mistake, some invitations were also sent to Mormons, and the affair created a scandal in the city, on both sides, many would-be dignified and prominent men being involved.

I went one term to St. Mark’s School. As I look back at it, it seems to me I must have been a queer pupil. In some of my studies I received excellent marks, in others I could make no headway. For history and geography I went up to the highest class in the school. My liking for these studies and my ability in them came, I am sure, from the earlier teaching I had received from old Professor Foster. In mathematics I went to the class below; in other studies I held with the regular class.

The term at St. Mark’s was the last of my school days. About this time I made up my mind to change my name from William Richard Haywood, Richard being the name of the uncle who had bound me out to the farmer and whom I therefore did not like, to my father’s name, William Dudley Haywood. My mother concluded that this could be done if I was confirmed in church. She was an Episcopalian. This was the last time that I attended a church service.

I heard Ben Tillman, Senator from South Carolina, lecture in Salt Lake City, and it was from him that I got my first outlook on the rights of the Negroes. In the course of the lecture he showed his bitter antipathy toward the Negro as a man and as a race. A Negro sitting beside me asked him a question; his reply was a ferocious and insulting attack, with reflections on the colored man’s mother. He referred to his questioner as a “saddle-colored son of Satan,” and went on to tell him what his mother must have been for the Negro to have been the color he was; this because the Negro obviously was of mixed blood. I looked at the Negro, and his pained expression caused me forever after to feel that he and his kind were the same as myself and other people. I saw him suffering the same resentment and anger that I should have suffered in his place; I saw him helpless to express this resentment and anger. I feel that Ben Tillman’s lectures must have made many other people feel as I did. It seemed to me that I could look right into the breast of old Tillman and see his heart that was rotten with hate.

I met other public characters when I was a bellboy in the Continental Hotel and the Walker House. One evening a tall, dignified man, sitting with his feet against availing in front of the hotel, asked me as I passed: “My boy, do you know who I am?” “No, who are you?” said I. He answered: “I am the world-renowned Beerbohm Tree, the great English actor!” I looked at him; I didn’t know what he was driving at.

I met more interesting people, whom I could better understand. There was a Lightning Calculator, who stopped at the hotel; my lack of ability in arithmetic caused me to think he was one of the world’s wonders. Then there was John L. Sullivan, who came through with a boxing combination; with him was Slade, a big Maori who came over to fight him, but Sullivan could lick a corral full like him. Sullivan I liked better than any of the rest. His show was at the Walker Opera House, in which I had a good seat. I saw him box with Herbert Slade, and knock out a man who tried to win the thousand dollars that he was giving to any one who would stand up against him during four rounds.

Dr. Zuckertort, the great chess player, stopped at the Walker House, and while there played simultaneously seventeen games blindfolded, which I thought a most remarkable feat. It so inspired me that I started then and there to learn chess.

While I was working at the Continental I was suddenly taken sick with typhoid pneumonia. I did not go back to my job at the Continental, and after my recovery my mother and I decided that I should learn a trade. In the house next to us was a family named Pierpoint. The man was a boiler maker, whose father owned a foundry and boiler shop. My mother spoke to the old man about me becoming an apprentice; but when they talked about drawing up the necessary papers I rebelled. I did not want to be bound out again as I had been to John Holden, where I could not quit until a certain term was served. My stepfather was then superintendent of the Ohio Mine and Milling Company in Humboldt County, Nevada. He decided that he could use me there. I bought an outfit in Salt Lake City, consisting of overalls, jumper, blue shirt, mining boots, two pairs of blankets, a set of chessmen, and a pair of boxing gloves. My mother fixed up a big lunch, mostly of plum pudding. She said: “You will be back in a few weeks.” Bidding my little sweetheart and my family good-by, I left for Nevada. I was then fifteen years old.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist.