Cyril V. Briggs, former leader of the African Blood Brotherhood and founding Black Communist, introduces Nat Turner to a new generation of revolutionaries on the anniversary of his 1831 execution.

‘Nat Turner, Negro Champion and Martyr’ by Cyril V. Briggs from the Daily Worker. Vol. 6 No. 209. November 7, 1929.

Put to Death By the Bourgeoisie of the South, November 11, 1831.

On November 11th, when the bourgeois democratic state celebrates its victory in the “war to make the world safe for democracy,” the Negro masses of America whose experience with bourgeois “democracy” has been bitter in the extreme, will do well to seek inspiration, not in a victory which means nothing to them and which, in spite of their part in it, did not help to better their condition one iota, but rather in an event of tremendous significance to them as an oppressed group under bourgeois democracy.

It was on November 11th in 1831, that the daring Nat Turner was put to death by the white slave-holders of Virginia following the collapse of the slave revolt he led.

John Brown invaded Virginia with 19 men, and with the expressed resolution to take no life but in self defense, Nat Turner, more resolute and capable, attacked Virginia from within, with only six men and with the determination to spare no life of the slave-owning class until slavery was completely crushed.

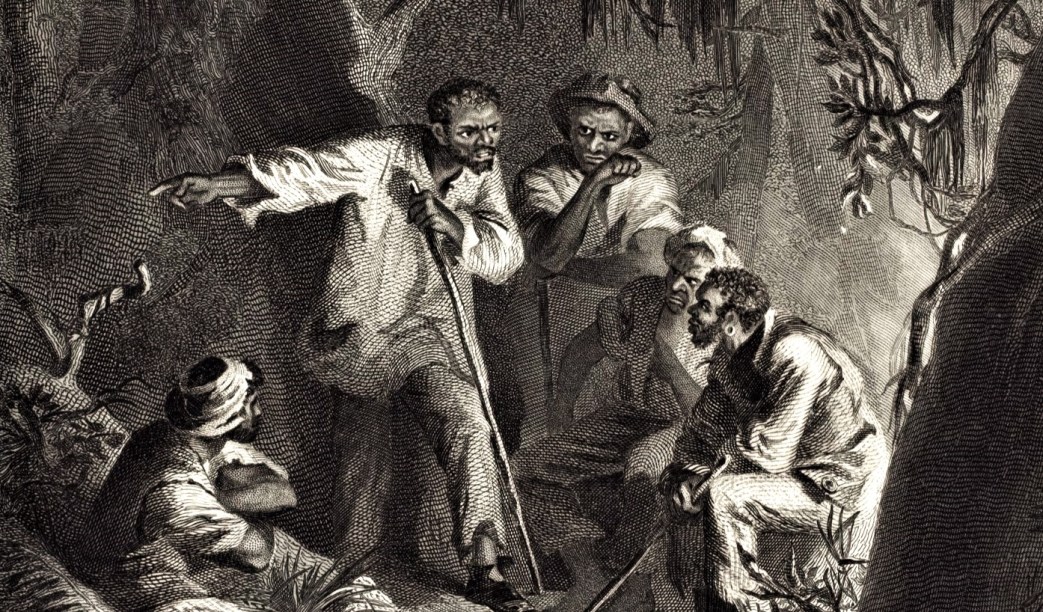

Upon the night of August 31, 1831, Nat Turner with his six followers set out upon their mission from the woods on the plantation of Joseph Harrison. As swift and stealthy as the Arab and white slave traffickers on their murderous missions through Africa, the black men passed from plantation to plantation, from house to house of the oppressors, not pausing, not hesitating, in the grim work of retribution. In one thing they were more humane than white and Arab raiders of African towns and homes: there was no gratuitous outrage beyond the death-blow itself, no insult, no mutilation; but in every house they entered, that blow fell on man, woman and child, no member of the white ruling class was spared. They entered only the homes of the plantation owners and overseers. The poor whites they didn’t molest. From every house they took arms and munitions. On every plantation they found willing recruits; these tortured slaves, so obsequious before their cruel masters the day before, so prompt to sing and dance and clown before his northern visitors, were all eager to chance their lives in the battle for liberty. Eagerly they grasped musket and sword, eagerly they followed the daring revolutionary.

The white slave-owners and their families quaked with fear in memory of wrongs inflicted upon the insurrected slaves, of Negroes savagely beaten, of many wantonly murdered. Remembering countless Negro women habitually polluted–the sisters and wives of the insurrectionists–the whites feared for their women a fate worse than death. But this fear was needless.

With a force of sixty adherents, Nat Turner judged it time to strike at the county seat, Jerusalem. This plan was eminently wise, and the revolt would have had a different history had not other counsel prevailed. Three miles on the way to Jerusalem, the insurrectionists had to pass a plantation owned by a man named Parker. Some of the men wished to stop here. Nat Turner was opposed to this, feeling that any delay might prove ruinous to his plans. Finally, however, he yielded, and it proved fatal. During the stop, a party of thirty armed white slave owners came up suddenly, dispersed the small guard at the gates and attacked the main body of the revolutionaries. The slaves responded to this attack with a volley of shots and a reckless charge on their armed masters, whereupon the latter broke and fled. Pursued they were saved from annihilation only by falling in with. another band of whites. Turner, faced with overwhelming odds, withdrew his men in perfect order. Later that night, however, he was attacked by superior forces and most of his men scattered. With only a few men left, Turner agreed that it was best for these to scatter and try to enlist more of the slaves for a fresh offensive.

At the outset, all his plans had succeeded; everything had gone as he predicted; the slaves had responded eagerly to his call; the master class had proved itself cowardly and incapable in the face of the revolt. Had he not been persuaded to pause at Parker’s plantation, he would have been master of Jerusalem with its huge stores of arms and munitions and would have been able to arm great numbers of slaves. His capture of Jerusalem would have further demoralized the slave holders. His exploits had already caused utter demoralization, not only in Virginia, but throughout the slave-holding section. Finally, if pressed, he could have taken refuge in the Dismal Swamp and there sustained his force indefinitely against the enemy, while he rallied additional forces to the cause of liberation.

All sorts of rumors filled the air and were reflected in the news- papers of that day. Reports flew thick and fast; the militia was said to be in retreat before the revolutionaries; the regulars had been defeated; thousands of slaves had joined the revolt. Blind panic took possession of the guilty white slave owners. Only with the arrival of U.S. troops and naval detachments did they recover from their scare, and then not completely until the capture of Nat Turner.

Nor was the range of these insurrectionary alarms confined to Virginia. Every slave-holding state was in the throes of terror! In Delaware there were arbitrary arrests and executions of slaves suspected of militancy. In North Carolina, many slave owners fled with their families to the swamps. In Alabama, the master-class trembled at the report of a joint conspiracy of two wronged races: the Indians and the Negroes. In Tennessee, in Kentucky, terror manifested itself in widespread arrests and murders of slaves. In Maryland, in Georgia, it was the same. But the greatest terror was in Louisiana. Captain Alexander, an English tourist, arriving at New Orleans at the beginning of September, found the whole city in tumult. Reports flew thick and fast of Negro uprisings throughout the South. And the state of mind of the master class was not helped by the reports which were constantly arriving of insurrections in Brazil and the West Indies.

The fact of thousands of white men in arms in all the slave state did not inspire the master class with any great sense of security. “Had not the blow been struck before by only seven men? Was not Nat Turner still at large?”

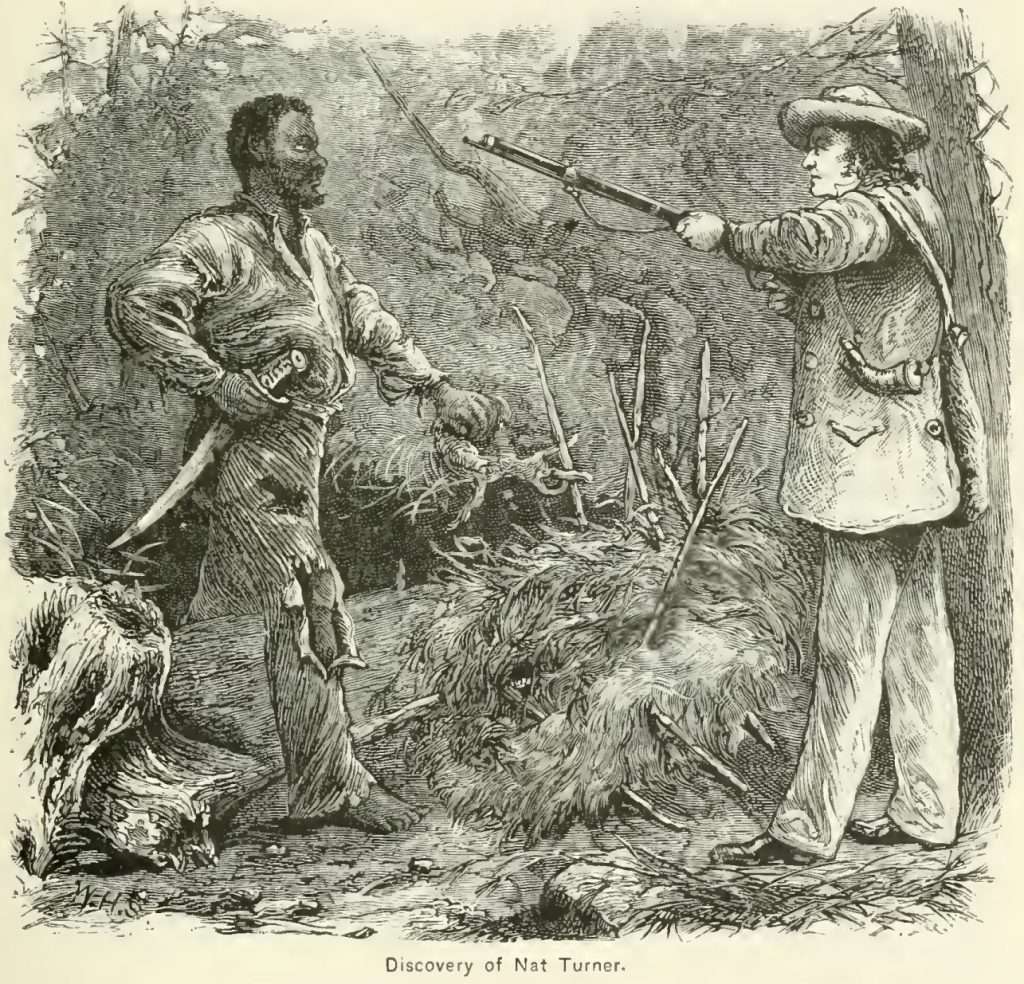

Meanwhile, the main cause of demoralization of the master class, the daring leader of the Virginia insurrection, was made the object of the most desperate search. Thousands of men hunted him in groups of one hundred and more. Huge rewards were offered for his capture. Several times the slave owners breathed with premature relief as false reports of his capture appeared. It was not, however, until October 15th that his whereabouts were discovered, and so able was he in concealing or in defending himself as the need might be, that it was not until October 30th that he was finally captured.

With Nat Turner captured, the slave owners launched a bloody reign of terror against the Negro slaves. Negroes were murdered in cold blood irrespective of whether they had taken part in the revolt. The slave owners were actuated by the usual motive of the ruling class of discouraging future rebellions against their exploitation by striking terror into the hearts of the slave-or working class. It was a reign of terror as ruthless, and as purposeful as that which the French ruling class wreaked upon the French workers following the collapse of the heroic Paris Commune.

Most of the revolted slaves refused to surrender, preferring to die fighting, to accepting the fate in store for those who fell into the hands of the enraged master class. Of those captured, many were tortured to death, maimed, and subjected to nameless atrocities. Any slave who showed the slightest spirit, or was noted for intelligence, was put to death by the slave owners who were in terror at the thought that there might be other, Nat Turners among their slaves.

Nat Turner took his capture with the utmost equanimity. Cool and fearless to the last, he made no denial of his leadership of the revolt, but like a good revolutionary he utilized the courts of the master class as a tribunal from which to thunder his denunciations against the op- pressors of his race. He was sentenced to death on the 5th of November, 1831, and was executed six days later, in November 11. Even his enemies record that “he met his death with perfect composure,’ that “he betrayed no emotion, and even hurried the executioner in the performance of his duty.” Not by the slightest movement of limb or muscle did he give any satisfaction to the huge crowd of sadistic slave holders who gathered to witness the “execution.”

Unlike the Negro petty-bourgeois misleaders of today, Nat Turner sought no personal advancement nor affirmed loyalty to a system under which his race was oppressed. He was “no soft-tongued apologist” in defending the rights of his race, but like the fearless Frederick Douglas, an uncompromising fighter against the ruling class of the day, the slave owners, he was a revolutionary fighter, in every sense of the term. When he struck for the liberty of his enslaved race he struck without fear, without hesitation. He sought the absolute destruction, the annihilation of the class responsible for the sufferings of his race. He struck at this class “without a throb of compunction, a word of exultation, or an act of outrage.” And he knew the use of terror to strike fear into the hearts of the enemy class.

While his plans did not succeed, Nat Turner nevertheless made his mark upon American history, and particularly upon the history of the oppressed Negro masses of America and upon the abolition movement. The famous hand of abolitionists, whose fearless eloquence prepared the white masses of the North for the move of the northern industrialists against southern competition through the price-cutting slave system, were but the unconscious mouthpieces of Nat Turner and other famous slave insurrectionists.

The Negro masses, whose oppression today, more than sixty years after “emancipation” is in many respects mere deadly than under chattel slavery, should strive to keep our revolutionary traditions alive as an example in the present phase of that long struggle our race has waged for real emancipation. The names of Nat Turner, of Gabriel, of Denmark Vesey, and of that famous revolutionary of Haiti, Toussaint L’Ouverture, should be indelibly engraved upon the consciousness of every Negro throughout the world. The revolutionary lives and deeds of our heroes must be made the example and guides for the prosecution of the struggle against the vicious capitalist system under which we suffer today as wage-slaves and exploited tenants.

Celebrate November 11 as Nat Turner Day!

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1929/1929-ny/v06-n209-NY-nov-07-1929-DW-LOC.pdf