Fred Isler looks at conditions for workers in the Puget Sound town of Bellingham, Washington.

‘Slavery in Bellingham’ by Fred Isler from Industrial Worker. Vol. 3 No. 12. June 15, 1911.

BELLINGHAM A SLAVE PEN–WORKERS WORN OUT WITH TOIL—PREACHERS GRINDING WELCOME IN MILLS TO PREACH CONTENTMENT TO WORKERS–AGITATORS BARRED.

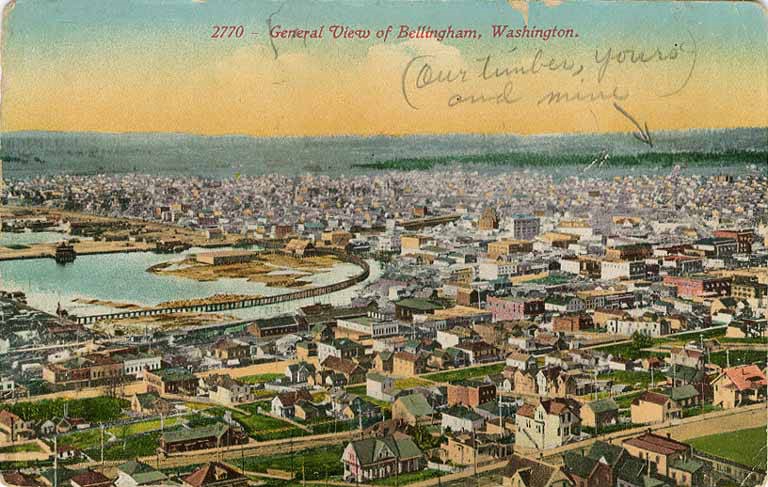

Bellingham, the “Metropolis and City of Lights” of Northern Puget Sound, is, without a doubt, one of the worst Hell holes of Capitalism along the Sound.

Several slave pens, otherwise known a’s saw mills, are doing business there and for the convenience of the mill owners, the safety of the lumber, and to keep the horde of hungry slaves from pestering the foreman with applications for jobs, and last but not least to prevent labor agitators from coming in contact with the slaves, the masters have surrounded their property with high fences.

The wages of the common laborers, slaving in the mills, range all the way from $1.50 to $2.00 for a shift of 10 to 13 hours.

As a result of receiving such a magnificent remuneration in return for the hardest of hard labor, those modern “Knights of misery” can only afford to feed on the cheapest kind of food, wear the scantiest of clothing and pass their earthly existence in the most dilapidated of shacks.

Through hard work and poor grub, the slaves generally develop their hands, feet and back, to the detriment of their brains and belly. They are mostly thin, emaciated and hump backed; their stomachs have a tendency to shrink instead of expand. A slick, fat and well dressed slave is quite a novelty, almost a curiosity. The mills of Bellingham cannot boast of having many.

Every now and then new machinery is installed in the bull pens, at other times they have to “clean up.” During that time the slaves are given a vacation without pay. Sometimes a mill will, during the busy season, shut down for several days at a time. In the winter time the masters will close the pen for one or two months, and while waiting for the reopening of the gates, the slaves have enough leisure time to sit and ponder on the beauties of capitalism. During that time the coffee and doughnut joints are well patronized.

Some of the mill owners, not satisfied with working their slaves to death, they sometimes take a notion to post some insulting notices round their mills and the following is a sample: NOTICE.

“When you work for a man, in Heaven’s name work for him.”

“If he gives you enough wages to buy bread and butter speak well of him.”

“Don’t loaf. You are getting paid to work.”

“You are part of the machinery, you ought to be proud of it.”

“Employees finding time to visit other employees and thus preventing them from working, please call at the office for your time.”

The above is posted at the office and also on the fence of Loggie’s mill, one of the most notorious sweat boxes in the city. In the yards of that mill, men are rustling lumber and loading cars for the princely salary of $1.50 per day. Those working as night firemen are getting $2.00 for a shift of 13 hours. The block pilers working on a ten block table are paid at the rate of $1.75 per day. To fill that job at Loggie’s a man must combine the speed of a racehorse, the quickness of a monkey and the strength of a mule. Twelve men quit that particular job during the space of two weeks, as they couldn’t stand the strain. During my stay in Bellingham, I never heard a slave speak well of Loggies, neither have I seen one boasting of being proud to be a part of his machinery. The whip of hunger and the lack of organization are the means by which those unfortunates are driven to slave for that slave herder.

Labor agitators are not welcome in the mills. They must keep from trespassing on “private” property. However when the workers come out to eat the contents of their dinner pails the agitator can talk to them.

While men who are trying to enlighten the mill workers on the subject of organization must stay out, the long faced, hypocritical sky-pilot is always welcome and received with open arms by the boss. That worthy makes a specialty of imposing upon the slaves at the noon hour. It is not enough for them to get hell all day while working, even when they have a short respite to enable them to eat their scanty meal, they must learn all about an imaginary Hell to come. With that object in view preachers visit the mills once a week. It would take too much space to describe some of the sermons of that dealer of celestial wings, however, some of the gems of wisdom peddled by the pilot are worthy of notice, and this is a sample:

“When you work you must do an honest day’s work for your boss.”

“A man working ten hours a day for two dollars has no kick coming; he is getting a good remuneration for services rendered.”

Amen.

That kind of bunk is music to the ears of the boss and sometimes to add more “decorum” to the bum show, the boss pretends to listen attentively to the squeaking of the heavenly messenger. Many of the workers hate the sight of the bible pounder.

Bellingham, like most of the Western Cities can boast of several “pluck’ the sucker” organizations, such as the Chamber of Commerce, the Young Men’s Commercial Club, Boosters’ Club, etc.; all these outfits are trying to boom a city of starvation wages, deserted houses, empty stores and the grave yard. At half past eight o’clock in the evening the streets are deserted. The reason is simple. The wave of purification following the visit of Billy Sunday has made the town dry and the slaves have to go to bed early so as to recuperate from the result of their grinding toil.

Stone and Webster is building an electrical line out of Bellingham, and with the understanding that the home guards would be employed in preference to outsiders, the business men of the town subscribed a huge sum of money; However the contractors have given so far the preference to men shipped by the employment offices. As a result the home guards are feeling sore.

The sentiment for Industrial Unionism is growing amongst the workers of the Northern part of Puget Sound. A strong agitation must be kept up there until every town, no matter how small has a strong Local. We can’t afford to rest upon our past work. Agitators and organizers should follow one after the other so as to keep things stirring. Those thousands of underpaid workers must be organized in the I.W.W. That’s their only salvation. The boss is uneasy when he knows that some agitator is in town. At the street meetings held in Bellingham during the last few weeks several of the basses were attentive listeners. They know well enough that in the future when the slaves are organized industrially, they will have to get off their backs.

The Industrial Union Bulletin, and the Industrial Worker were newspapers published by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) from 1907 until 1913. First printed in Joliet, Illinois, IUB incorporated The Voice of Labor, the newspaper of the American Labor Union which had joined the IWW, and another IWW affiliate, International Metal Worker.The Trautmann-DeLeon faction issued its weekly from March 1907. Soon after, De Leon would be expelled and Trautmann would continue IUB until March 1909. It was edited by A. S. Edwards. 1909, production moved to Spokane, Washington and became The Industrial Worker, “the voice of revolutionary industrial unionism.”

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrialworker/iw/v3n12-w116-jun-15-1911-IW.pdf