Remarkable working class solidarity shown in this press statement by the over 1000 striking miners on their experience being rounded up by gun thugs in Bisbee, Arizona, placed on box cars and forcibly deported 175 miles away to the empty New Mexico desert. The deportations were part of a wave of murder, arrests, mob violence, and repression that hit the workers’ movement that summer.

‘Statement of Exiled I.W.W. Miners’ from Solidarity. Vol. 8 No. 394. July 28, 1917.

THE BLOT ON “DEMOCRACY”–Thrilling Story of the Bisbee Deportation Told by Press Committee of the Exiled I.W.W. Miners–Homes Broken Into, Men Robbed, Women Assaulted, Stores Closed Down–Mob Law Rampant When Bisbee’s Corporation Thugs Deport Union Men for Refusing to Scab–STRIKE UNBROKEN–MINERS MORE DETERMINED TO WIN THAN EVER

I.W.W. Detention Camp, Columbus, N.M., July 21, 1917. July 12, 1917, is the day that we will remember for a lifetime. The master class, beaten at their own game of law and order, lost no time in using other methods which suited them better. The mines of Bisbee were practically shut down; the mine owners of Wall street were losing thousands and thousands of dollars daily and hourly. Parts of the mines were caving in, but rather than grant the workers their modest and just demands they resorted to mob rule. The happenings of the last few days have been of great educational value not only to the 4,500 striking miners of Bisbee, but to slaves all over the world.

Small business men, inflamed by the local kept press and the corporation’s howls, and of course as they considered their economic interest to be with the masters instead of with the advancing proletariat, they lined up against the miners. Also the broken-down faithful slaves who had been scabbing lined up at the crack of the whip with bankers, lawyers and high-salaried managers. Of course all the white-collared slaves were in the “lawn order” bunch of self-styled “patriotic citizens.”

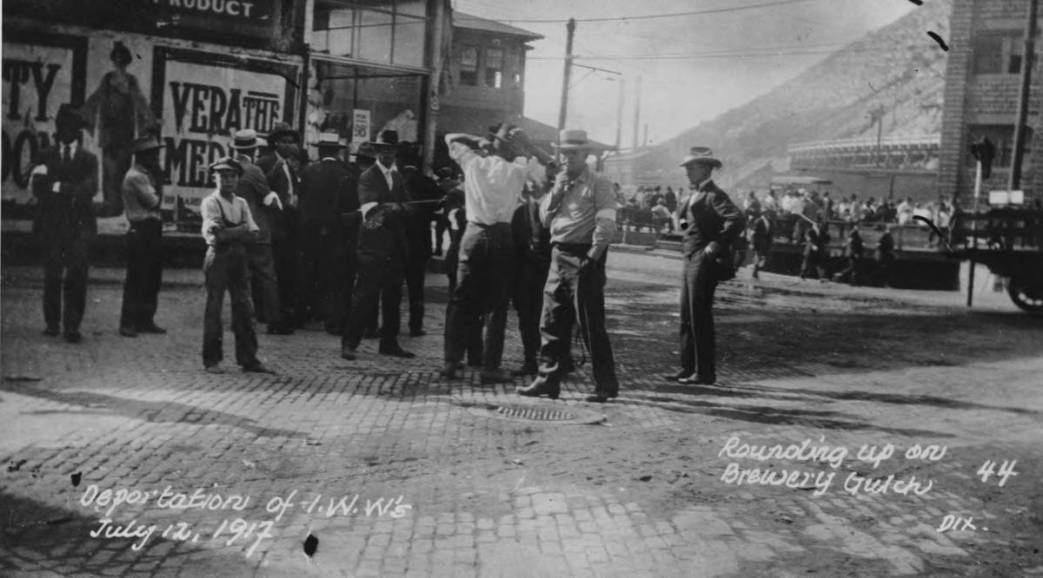

These were the people who did the masters’ dirty work. Business men from Tombstone and Douglas came into Bisbee in the small hours of the morning, altogether forming a posse of 1,200. They were deputized by the servile sheriff, who was determined to serve his master well. Some were deputized by telephone; they wore white handkerchiefs around their arms. Many wore big tin stars, of which they were very proud. Most all of them had either six-shooters or automatic pistols, and also carried a high-power rifle or a riot pump gun.

This deputized mob representing “law and order” started out about 5 a.m. on their campaign of terrorism and anarchy. They rounded up men of every description, as they appeared on the street one by one. Not satisfied with that, gangs of 20 and 30 commenced to raid and ransack private houses. They dragged married men from their beds. One man was dragged from his wife, who bore a child two hours after he was deported. Many women were beaten and insulted. Money and clothes were stolen openly. We learned a great lesson in “law and order.” Two restaurants were closed by order of the Sheriff’s legal mob; the proprietors, cooks, waiters and dishwashers were driven to the cattle cars at rifle points. A prominent lawyer was also corralled, and anyone who openly sympathized with the miners or showed any tendencies of being a thinking human being was rounded up and herded in the Post Office square, which was surrounded by hundreds of the vigilantes, many of whom were nervous Y.M.C.A. boys, who kept their fingers on the triggers, while their knees were shaking.

The miners were taken altogether by surprise, and not being armed took the situation philosophically. We had been peaceful and orderly since the beginning of the strike. They had instilled the doctrine of law and order into us night and day. But we were disillusionized on that memorable day, July 12th. The sight of these human hounds with rides leveled taught us a lesson long to be remembered by all the working class. The corporations, beaten and on their last legs, threw off the mask of respectability and assumed their true character of murderous thugs. Several women are badly beaten and many of the men have cut and bruised heads. Two were killed, a gunman and a fellow worker. The Fellow Worker’s name was Brew; he worked at the Dean mine before the strike.

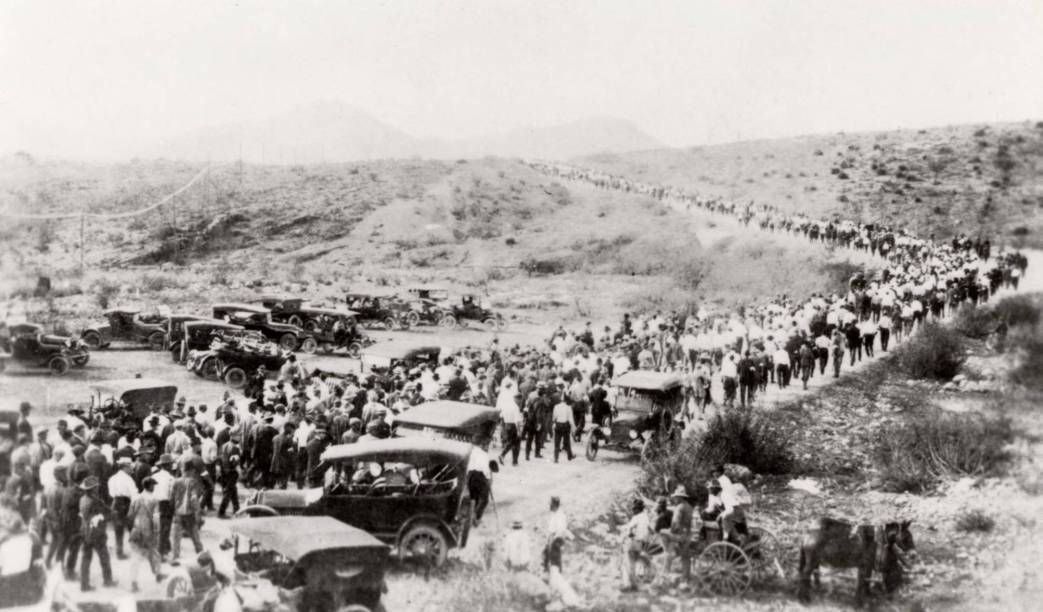

After they had got enough of us together, we marched down the Canyon to Warren, lined on each side with the scaly snakes. We then were herded into the ball park at Warren, and then we started to cheer. This was probably one of the greatest exhibitions of solidarity ever shown. Fellow Workers made speeches in Spanish and English amidst the roaring cheers. The air was blue with curses, and we swore to stick together whatever might happen. Guns were aimed at the workers; women and young and old were shouting defiance at the human monsters who were breaking up their homes. It seemed for a few minutes as if the social revolution was on. We were defenseless, but our spirit was unbroken.

Another bunch was marched into the park amidst deafening hurrahs. We replied with wild cheers; hats went up in the air, and the thousand deputies again leveled their guns. A never dying working class solidarity there and then formed in all our hearts. We had learned that the master class only uses law and order methods when that suits them beat.

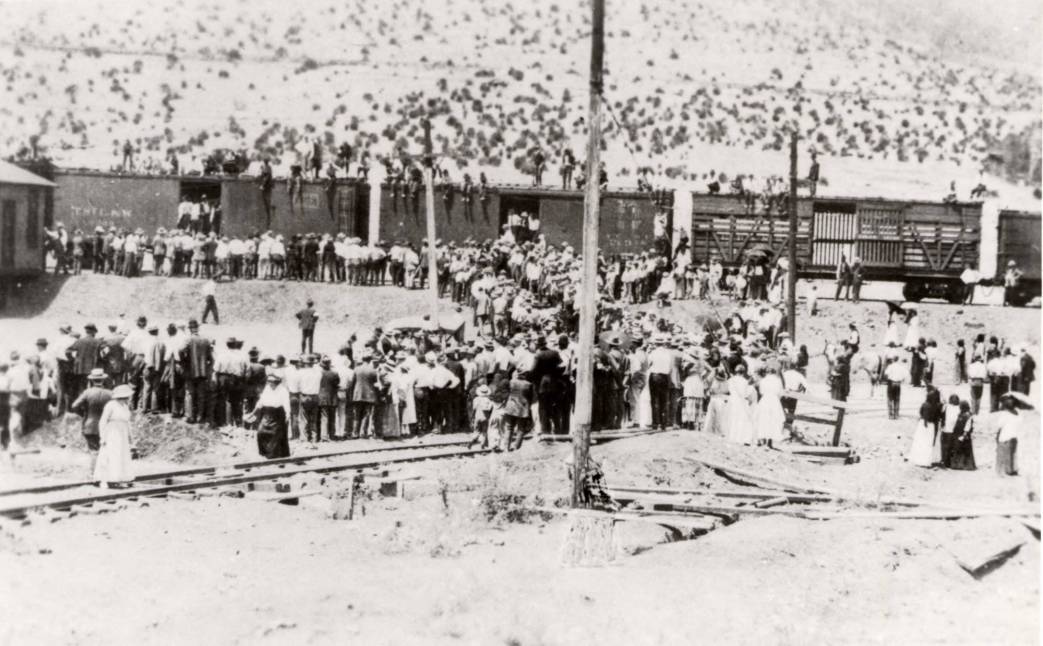

The Sheriff of Cochise County, upon whom the responsibility for the whole affair fell, sent unarmed men over to our side of the park to parley with us. They announced that any of us who would go back to work would be released. In answer to the question, an ear-splitting chorus of “No” was heard for minutes. Our solidarity was complete: only three or four weakened out of thirteen hundred. After a few hours a train of 24 cars, mostly box cars and a few cattle cars, backed up the hill from Douglas. We formed in bunches of about fifty and were loaded into these, cheering and singing “Hold the Fort.”

Many of the men had lived in Bisbee for years, had wives and children; many had property and money in the bank. But in this mad frenzy of “law and order” all were loaded in the hot and filthy box cars. About 600 gunmen got on the top, and the union scabs hauled the train away.

We passed through Douglas, where a number of vigilantes were on hand with more rifles, to guard against our getting off the train. All telegraph and telephone service was censored. The manager of the Western Union Telegraph Co. said afterwards that he thought that it was an army captain who ordered him not to send any messages relating to the wholesale deportation. It turned out that the man who played censor was the manager of the Copper Queen smelter in Douglas, and when questioned he said that he was acting on authority of the Sheriff. The Sheriff who was elected as “the working-man’s friend” tried to shift the blame on someone else; he was one of those who “captured” the union hall.

The day before the raid the Mayor of Bisbee, who is a foreman in the employ of the C. & A. Co., said that he hoped we would lose, and he issued orders denying us the use of the City Park. The propaganda of the One Big Union was (and is) spreading like wildfire throughout Arizona; the workers were beginning to wonder why the copper barons should enjoy all the good things of life, while the workers who produce everything were not even given a decent living. The corporations were desperate; the slaves were getting wise. Little did the masters know that their inhuman treatment of us and our wives would help our cause and be the means of issuing hundreds more red cards to the now awakened slaves, who realize that their only hope is to organize, and organize right in the One Big Union.

The train rolled on until we reached Columbus, N.M., 174 miles from Bisbee. There the vigilantes left us and went up town; they thought that we would scatter to the mesquite and disband; they did not take into consideration the fact that we were organized. We remained in the cars, and pretty soon the gunmen came back. The authorities in Columbus had arrested the head gunmen and the railroad superintendent who was in charge of our train for bringing us forcibly into Columbus in defiance of all law. They told the other gunmen to leave town immediately and take the train back with them. So the engine coupled on the tall end and started back west again. At Hermanas the gunmen left us and caught a train back to Bisbee. We with our 24 box cars were ditched there in the desert. No water and no food, there was much suffering amongst us. Hermanas has a population of about ten people, besides a company of soldiers stationed there. The soldiers had only enough provisions on hand for themselves, and so could not help us. We laid out in the hot desert sun all the next day, Friday, with nothing to eat. The soldiers furnished us with plenty of water, and by evening a car of provisions came from the government Quartermaster corps at El Paso. There was no one to “guard” us all the time we were on the desert at Hermanas, but only a very few men left out of the whole bunch. We were determined to stick together. No one was forced to stay, but we all agreed to stick together. We had speeches and singing, and cries of “Viva la huelga” came from our Mexican Fellow Workers.

Next morning a troop of soldiers came from Douglas, and they coupled on our box cars, and we came into Columbus again, Here the federal government took us in charge and we pitched tents in the refugee camp. We are now here awaiting further orders. Up to this date the vigilantes are still active in and around Bisbee in defiance of law and our constitutional rights. Governor Campbell has appealed for federal troops in Bisbee, as all the state troops are in government service.

PRESS COMMITTEE

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1917/v8-w394-jul-28-1917-solidarity.pdf