Becoming a ‘basic industry’ around World War One, Leon Platt provides this major survey of the history and political economy of the rubber industry.

‘The World Struggle for Rubber’ by Leon Platt from The Communist. Vol. 6 Nos. 2 & 3. April & May, 1927.

1. RUBBER: ITS ORIGIN AND HISTORY.

RUBBER is one of the raw materials, which has assumed importance for all countries. Like the fight for coal, iron, or oil, the struggle for rubber has disturbed the relations between the great powers. The beginnings of the epoch of the regime of rubber are to be found in the late world war.

The development of the motor car, the tires of which alone consume four-fifths of the rubber import, has accelerated the development of the rubber industry. To this can be added the 32,000 articles in the United States that are partly or wholly made of rubber, as well as the 51 million miles of insulated telephone and telegraph wires.

Rubber was a peaceful industry. Rubber was a product that grew in tropical jungles. Few concerns were engaged in its collection. To the outside world it was connected with heroism and danger, and looked on as an adventure to the rubber seekers. Not until recently did we have a rubber question. The first open conflict for the control of rubber occurred between England and America. This conflict has emphasized the fact that, unlike coal, iron, or oil, the area in which rubber can be produced is limited. The countries lying in the tropical belt ten degrees north and south of the equator are alone suitable for rubber growing.

Besides the particular geographical position of the rubber producing countries, there must also be exceptional climatic conditions to make rubber growing possible. This is characteristic of rubber more than of any other raw material.

The scarcity of the wild rubber supply for our industries forced us to seek other sources. We began to plant rubber like coffee, tobacco, etc. At present there are two sources that supply the world’s rubber. One, the rubber obtained from plantations, the other, wild rubber. As recently as 1905, most of the world’s rubber supplies were of wild rubber, which was collected from the trees of the Amazon region of South America and from that part of Africa known as the Belgian Congo. The world’s total rubber production in 1905 was 54,494 tons. Of this, plantation rubber constituted only 174 tons or one-third of one per cent, while of wild rubber there were 59,320 tons or 99 and two-thirds of one per cent.

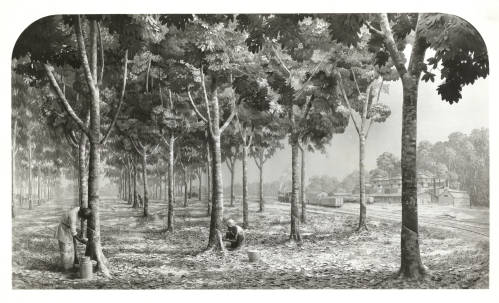

In 1925, the composition of the world’s rubber supply was different. Of the total rubber production of 505,000 tons, 35,000 tons or 6.3% was wild rubber, while plantation rubber amounted to 470,000 tons or 93.7%. With the change in the composition of the world’s rubber supply also changed the place where rubber was produced. Now the main sources of supply are the Straits Settlements and the Dutch East Indies.

There is another way in which rubber differs from other raw materials. The deposits of oil, coal or iron bear profits as soon as exploited. But returns from rubber plantations is a question of years. To clear the jungle so as to make it fit for rubber plantations takes one or two years. After the rubber trees are planted it requires five or six years till the trees reach maturity ready for tapping. So it takes six to eight years to make rubber a paying proposition.

Another factor necessary for rubber planting is cheap labor at the rate of 10c to 25c per day. This is not because the selling price of rubber does not permit a decent living wage. (Rubber on the New York market is sold 300% above the cost of production.)

The assurance of the invested capital as well as interest is achieved by the rubber imperialists through the permanent control of the rubber producing countries. They make the laws fit their policies of exploitation, allow the plantation owners an unlimited ownership of land, and shape the immigration laws so that they will not seek the Chinese coolies from plantation areas to compete with native labor. Southern Chinese and Indian coolies are hired by contract for a period of three years, becoming virtually the property of the plantation owners.

As the Bankers’ Association Journal of August, 1922, said, there must not be “Any political meddlings in the rubber producing country.” In other words, a country where rubber is produced must be subjected to the control of the world power, whose capital is invested in the plantations, and any discontent or movement for national independence cannot be tolerated.

2. CONTROL OVER THE RUBBER PRODUCING AREA.

In the struggle for rubber two important groups are playing the dominant role: 1. The owners of the rubber plantations which are monopolized by English capital. 2. The rubber manufacturers, of which the American are the most important, consuming 75.6% of the world’s rubber.

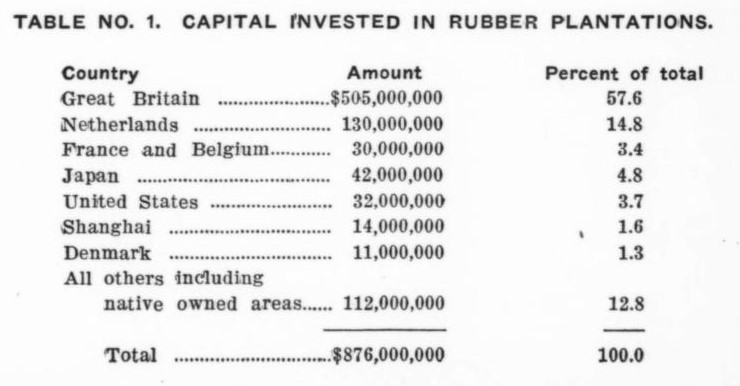

Although America is the world’s largest rubber consumer, American capital controls an unimportant fraction of the world’s rubber plantations, as can be seen from the table given below.

America does not produce nor control rubber, but it is very important for her industries. It is like sisal, manganese, potash, nitrates, etc…for the supply of which she depends upon other countries. From the viewpoint of American imperialism the control of that product is urgent. Rubber is essential for certain important instruments of war, and the monopoly of a product of such importance is menacing to the United States. Great Britain controls 75% of the world’s rubber, the United States consumes as much. This makes America’s needs of rubber dependent upon Great Britain.

The investments of the United States in rubber plantations are insignificant when compared with the British or with the financial resources of the United States. Actually, British capital invested in rubber plantations is more than $505,000,000. For 26% of the capital invested in the Dutch East Indies plantations is British capital, making a total of $538,000,000 of British capital invested in rubber plantations. The importance of the British rubber plantation is, that 69% of the 75% of the world’s planted acreage controlled by Great Britain lies in the territory of the British possessions and is under the protection of the British flag. (Map)

3. THE WORLD’S PRODUCTION OF RUBBER.

With the development of the automotive industry, came the increased production of rubber. For a long period in its history rubber was used chiefly for articles other than automobile tires. As recently as 1910, the rubber from Brazil and the Belgian Congo represented 91% of the world’s total supplies. The reasons why these two countries lost their predominance in the rubber world are:

1. The wild rubber trees, to which access was easily gained, curtailed their production.

2. The exploitation of the natives reached such a stage, that the latter refused to gather rubber under the existing conditions of labor.

3. The excessive export duties levied by Brazil and the cultivation of a new product—coffee—of which Brazil now a monopoly.

4. The decline in price, and the unsuccessful competition with plantation rubber.

The increased production of rubber naturally comes from the increased planted area as well as from the increased productivity of each planted acre. In 1920, in the whole Middle East, 120,000 acres were planted with “Havia Brazilian.” During the period of 1906-1920 the planted acreage increased on the average of 250,000 acres yearly. According to the India Rubber Journal of January 16, 1925, the planted area increased to 4,915,000 acres. In 1910 the yield per acre was 157 pounds, today it is 346 pounds in the British Malayan estates and 334 in the Dutch East Indies.

4. WORLD CONSUMPTION OF RUBBER.

The industry that consumes the largest share of the world’s rubber is the tire industry. In 1911, America produced 209,974 automobiles; raw rubber consumed by the automobile industry in the same year was 3,300 tons or 10% of the rubber imported into the United States. In 1925 we produced 4,175,365 automobiles and raw rubber consumed for tires was 320,380 tons or 83% of the total rubber imported into the United States, which is approximately 66% of the world’s consumption for all purposes. The increased consumption of rubber manifests itself, not only in the automotive industry, but in other industries as well. The increased consumption of rubber is not due to America alone, although America has the largest automotive industry. Out of the world’s total of 24,564,574 automobiles, 19,964,347 or 85% are in the United States. The increased consumption of rubber is also true of other countries.

A factor in the increased American demand of crude rubber in the last two years was the wholesale adoption of the balloon tire, which requires from one-fourth to one-third more rubber than the high pressure type. The production of balloon tires during 1925 was equal to more than one-half the output of cord and fabric tires combined. Another factor is the increased production of buses. The rubber consumed by one bus is equal to that used in twelve passenger cars.

5. THE IMPORTANCE OF RUBBER.

The importance of rubber can be analyzed for two periods. 1—In time of peace. 2—In time of war.

At the beginning of this article we gave a general view of the uses of rubber. In the United States a few very important industries depend on that raw material. One of these is the automobile industry, one of our largest national enterprises depending on rubber for its tires.

The importance of the automobile is well known. Not only does the automobile serve our local needs, but lately it has begun to compete successfully with railway and street car transportation. Each of the 20 million automobiles in the United States requires five tires yearly. The average yearly rate of increase of automobiles since 1920 is 20%. Here we have stressed only the importance of the automobile in time of peace. How about wartime?

“It was the use of motor transportation on a large scale which enabled Marshal Foch to hammer the enemy army into fragments.” (Delaise, Oil and Its Influence on Politics, p. 29.)

How did this come about?

“During the defense of Verdun, situated at the end of a wretched railway, the destruction of many railway lines and the inadequacy of the system behind the front, led the generals to transport their troops more and more frequently by motor lorry.” (De La Tremerye, The World Struggle for Oil.)

The importance of the automobile for war purposes is here clearly emphasized. The automobile is not the only product which depends on rubber. There are other instruments of war in which rubber is essential. Airplane bomb cushions, tires and gas protectors, respirators and helmets for airmen, suits for men on submarines and battleships, hose and tubing for gas attacks, trench pumps, ships, airplane, vacuum cleaners, insulated and water proof material, etc.

“The vital part which all raw materials play in war was amply demonstrated by Germany’s predicament during the last conflict, and rubber was one of the things needed most.” (The World’s Work, February, 1926. Rubber, an International Problem.)

How and where did the United States get its rubber to satisfy its war needs? Harvey Firestone answers this question:

“Mr. Firestone declared that during the war the United States could not get a pound of rubber except by the consent of the British Government.” (Far Eastern Review, January, 1924.)

But in case of war with Great Britain, where will the United States get its rubber? It is in this problem that the whole story of rubber is involved. As H.N. Whitford, special agent of the Crude Rubber Department of the United States Department of Commerce, said: “In time of war the conditions might be such that the United States would be cut off entirely from its supplies.”

The problem before the United States at present, is to grow rubber to supply its war needs in time of peace as well as in time of war.

6. THE CONDITIONS OF THE RUBBER PLANTATION WORKERS IN THE MIDDLE EAST (Straits Settlements and Dutch East Indies).

The workers employed on the rubber plantations are Chinese and Indian coolies. They work under the system of indentured labor. The Chinese coolies are recruited in Southern China and hired by a contract which they do not sign nor understand, for a period of from two to three years. The daily wage of the rubber plantation workers in the Dutch East Indies is fourteen cents (American currency) for men, and twelve cents for women.

The aims and character of the system of indentured labor are:

“According to the coolie contract the laborers are subject to laws which compel them to work and prevent them leaving the estate until the expiration of the contract…The laborer is looked on as a pawn to be moved at the will of the administrators.” (United States Department of Commerce Trade Information Bulletin No. 27. Rubber Plantations in the Dutch East Indies and British Malay.)

It should be noted that the League of Nations approved the principle of indentured labor in several tropical countries.

The system of indentured labor makes it extremely difficult for the colonial workers to free themselves from the yoke of British and Dutch imperialism. In the Dutch East Indies the labor ordinance provides that the inciting of laborers to desert by furnishing lodging, or engaging of workmen who have no letter of discharge or similar document showing them to be free of liability for service to others, is punishable by a fine of 200 guilders ($72) or one month’s imprisonment; natives violating the above provisions are punishable by a fine of 50 guilders ($18) or one month’s labor on public works without wages. (United States Department of Commerce Trade Promotion Series No. 2. The Plantation Rubber Industry in the Middle East.)

How do the American rubber imperialists threaten the plantation workers in the Middle East? The largest American owner of rubber plantations in the Middle East is the United States Rubber Company, controlling about 117,000 acres. Below is a brief account of the conditions under which the colonial workers toil on the American rubber plantations.

“The indentured system is still in vogue, and it is hoped in the interest of both laborer and planter that the present system will not be interfered with by legislature. The coolies agree to enter the service …. fora period of three years at a fixed wage. If they break the contract and abscond, their employer is protected by his agreement by their arrest and return to the estate.” (Annals, March, 1924.)

The United States Rubber Company employs on its rubber plantations a force of 20,000 men, paying them a daily wage, for men 19c gold, for women 17c. The net profit of the United States Rubber Company in 1925 was $17,309,870.

7. THE CONDITIONS OF THE RUBBER WORKERS IN THE AMAZON REGION.

The conditions of the rubber workers in South America should be considered in two periods.

1—Labor conditions before the world war.

2—Labor conditions after the world war.

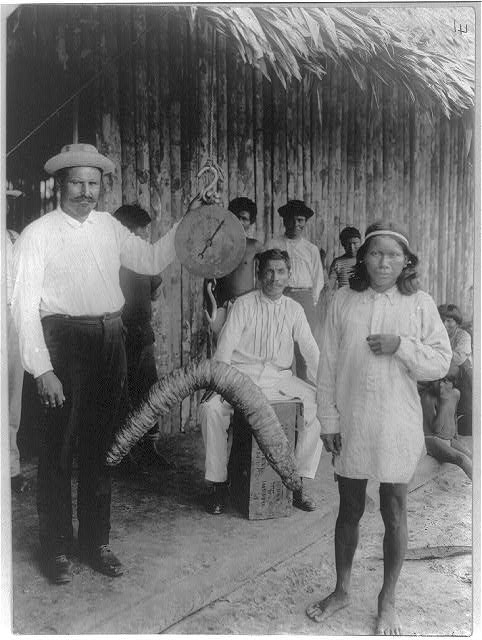

Although the conditions of labor differ but slightly in these two periods, yet for a definite reason we must analyze these two periods separately. Up to the end of the first period Brazil was one of the largest producers of rubber and the labor conditions were determined by the rubber-gathering concerns. The Indian workers were not employed on plantations, for no rubber trees were planted in Brazil. The trees grew in a wild state around the Amazon Valley, and the natives had to penetrate the jungle to gather the milky white “Latex.” They perfromed this work unwillingly. They were forced to gather the rubber under the threat of death. Whole communities of Indian workers were murdered by the rubber pirates—the Peruvian Amazon Company (a British concern). This is what the British ambassador wrote to the United States secretary of state, May 8, 1911:

“…there is no exaggeration in the accusations of Mr. Hardenbur (author of “The Lords of the Devils Paradise.”—L.P.) In one district, for instance, 40,000 of a population of 50,000 Indians have been either killed outright or tortured to death.” (U.S. 62nd Congress, 3rd Session House Document 1366, Slavery in Peru, p. 119.)

In some cases the Indian was engaged as a laborer and paid in kind. The Indian was forced to take a worthless article for which an exorbitantly high price was charged, and repay with services in rubber gathering. The rubber companies make it impossible for the Indian to repay his debt. By advancing him more goods, he continually served the company.

“Say what you will it is nothing more nor less than forced labor, whether it is secured and kept by the rifle or by a system of peonage based on the advances of merchandise…” (I.B.I.D., p. 60.)

What are the conditions under which the workers collect rubber today? This question has a two-fold importance.

1—These conditions are not limited to the rubber industry. The same conditions prevail on the Brazilian coffee plantations.

2—The Amazon region was recommended by the United States Department of War as the second place where the development of rubber plantations by American capital is advised.

The United States Department of Commerce appointed a special commission to study the possibilities of growing rubber in South America. The commission reported.

“As explained elsewhere in the report, the wage system is not in practice in the American rubber industry. The rubber worker Is paid according to the amount of rubber he collects. This is placed to his credit and against it are debited the initial advances made to him for transportation. working tools and other supplies and all other subsequent purchases at the company store. If he has a favorable balance at the end of the year he may receive the amount in cash, but it is common to laborers to continue indefinitely in debt to their employer.” (United States Department of Commerce Trade Promotion Series No. 23.)

The basic wage in that region is 25-27 cents per day.

8 THE CONDITIONS OF THE RUBBER WORKERS IN BELGIAN CONGO.

The natives of the Belgian Congo, inhabiting a country which is situated in the rubber belt, met with the same fate as the Indian workers of the Amazon region. The rubber industry in the Belgian Congo was in the same state as in South America.

The activities of the rubber imperialists were first known to the outside world, through their operation in the Belgian Congo. What was said regarding the atrocities of the Peruvian Amazon Company in the Putmayo region, holds good for the rule of King Leopold and the Congo Rubber Company in which he held controlling interest. Rubber was to the Negro what it was to the Amazon Indian.

“The natives of the exploited rubber zones are crushed, broken, sick unto death of the very name of rubber…. ‘RUBBER IS DEATH’ HAS BECOME THE MOTTO OF THE RACES.” (E.D. Morell, Red Rubber, p. 150.) .

Under this system $68,573,320 worth of raw materials (95% of rubber and the balance of ivory, has been forced out of the Congo natives for six years. The profits of the Congo Rubber Company for that period have amounted to $3,650,000 on a paid-up capital of under $50,000; each share of a nominal value of $100 having received in that period dividends totaling $1,475.

9. UNITED STATES RUBBER PLANTATIONS IN LIBERIA

AS was already shown the world’s rubber plantations are under A the control of foreign capital. The United States controls an insignificant part of the world’s rubber and is dependent on foreign supply. In the last year many attempts were made by the United States rubber manufacturers to produce their own rubber and free themselves of foreign monopoly. Commissions were sent to all countries of the rubber belt to investigate the possibilities of rubber growing. One of these commissions visited Liberia, and reported favorably on the possibilities of future rubber production in that country.

Harvey Firestone took the initiative in the development of rubber plantations in Liberia. This marks the beginning of the entry of American imperialism into the exploitation of foreign rubber fields on a large scale. Liberia is a little black republic with a population of two million. It is situated on the Atlantic coast of South West Africa. Mr. Firestone obtained from the Liberian government a concession of a million acres, to be exploited for rubber plantations. This little country is in a very backward stage, having only fifty miles of roads and although situated on the Atlantic coast it has no big ports to accommodate big vessels. To develop the million acre concession Mr. Firestone will employ 350,000 Liberians. He will develop the country’s commercial and industrial resources. In addition to that, arrangements have been made for the floatation of a five million dollar loan to the government of Liberia.

Why did Mr. Firestone pick on Liberia for rubber plantations? According to the New York Times of June 17, 1925, the reasons are the following:

1. The Liberian will work for less than the laborer in Malay. The labor cost will be 50 per cent less than in the Malay Peninsula.

2. The United States has a moral protectorate if not a direct protectorate over Liberia.

No interpretations are necessary to the above. The United States rubber trust wants to make the little negro republic an American colony. The following factors will successfully accomplish their aims:

The provisions of the loan include supervision of the country’s custom receipts and in fact supervision over the entire financial regime with American experts acting in the most important capacities. Direct colonization and military supervision of the country’s affairs. The following was recommended by Dr. Johnson, minister to Liberia (1918-1922):

“An American naval base and coaling station should be established on the Liberian coast…is essential to the success of the Firestone concession in Liberia.” (Rubber Age, Nov. 10, 1925.)

At present Liberia is virtually considered an American protectorate. According to the plans of the American rubber imperialists Liberia will completely lose its political and economic independence.

As regards the conditions under which the 350,000 will toil on the American plantations this can be said: According to Mr. Firestone the native Liberian will work for less than the native Malayan. He can get all the labor he wants for 24c per day. The cost of living in Liberia is not less than in the Malayan Peninsula, but the wages of the Liberian worker will be less than the Malayan. We know the conditions of labor in the Middle East, now we can see what are the conditions of the Liberian rubber workers.

10. RUBBER AND THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS

In 1928 the United States congress appointed a commission to investigate the possibilities of rubber growing in the Philippine Islands. In addition to that Mr. Firestone made a personal investigation regarding the same matter. It was reported that the Philippines are suitable for rubber production, especially the Mindao islands where 1,500,00 acres could be utilized for rubber plantations. It was stated that in exploiting the Philippines full possibilities of rubber growing, the islands could supply America’s needs of rubber in a period of 6 to 8 years. However up to the present time no rubber plantations on a large scale were exploited by American capital. This can be explained for two reasons:

1. An important and necessary factor in the development of rubber plantations is an abundant supply of cheap labor. The wages of the Filipino laborer is relatively higher than the Liberian and Chinese coolie. In the Middle East the question is solved by importing Chinese coolies to work on the rubber plantations. The Philippine legislature not wanting to lower the standards of living of the Philippine workers to the status of a coolie, prohibited the immigration of oriental labor into the Philippine Islands:

2. The rubber plantations in the Middle East embrace areas of hundreds of thousands of acres. This privilege the American capitalists cannot enjoy in the Philippine Islands. According to the Jones law the jurisdiction over the land is intrusted into the hands of the Philippine legislature, which has limited the ownership of and by individuals or corporations to 2,500 acres. The passage of these laws by the Philippine legislature, and its resistance to the attempted changes, are given by Manuel Quezon, president of the Philippine Senate.

“The reasons for our attitude (against changing the land laws. L, P.) are both political and social. Politically we fear that the ownership of large tracts of lands by American capital would increase the opposition to our further independence and perhaps actually prevent congress from granting it.”

Unfortunately the Philippine Islands are blessed with rich natural resources and their soil is suitable for rubber plantations of which America is in such great need. To break the stubborn resistance of the “uncivilized” Filipinos who do not want to be exploited by American capitalism. The American imperialists suggest the following:

“Mr. Hariman (president of the Hariman National Bank) holds that two important legal steps are all that is necessary to insure the cultivation of rubber in the Philippines on a large scale. The first he said is to convert the islands into a territory of the sort that was made out of Hawaii, Porto Rico, Panama and Alaska. American capital, the New York banker asserts, would flow into the Philippines as soon as territorial status guarantees stability of government.

“The second step, Mr. Hariman says, would be the change of the Philippine land laws, so that unlimited acquisition of territory would be available for the rubber industry’s needs.” (Science Monitor, Nov. 1, 1925.)

Today there is a bill before congress, introduced by representative Bacon of New York, which would secede the Mindanao Islands, Hawaiian, Bazila and Lulu Archipelago from the Philippines, and put them under direct American control.

Under the pretext of developing the industrial and natural resources of the islands, President Coolidge sent a personal representative to the Philippines. Colonel Thompson, president of the TodStambough Iron Ore Co. and a member of the “Ohio Gang” in his official report, accepted by President Coolidge, published in the New York Times on December 23, 1926, the status of the islands was definitely defined. No longer can the Filipino people have any illusions of getting their immediate independence. The second of his twelve proposals reads:

“That the granting of absolute independence to the Philippines be postponed for some time to come…”

In general Colonel, Thompson’s report accomplishes the wishes of Mr. Harriman, and turns the Philippine Islands into a territory like which we made of Porto Rico, Alaska, Panama, etc.…In his third proposal he recommends that the United States government creates a special department—a colonial office to rule the Philippines as well as all our other over sea possessions. The tenth proposal is:

“That the Philippine legislature should amend the Philippine land laws…so as to bring about such conditions as will attract capital and business experience for the development of the production of rubber, coffee and other tropical products, some of which are now controlled by monopolies.”

However, the most vivid expression of dollar diplomacy is said in the twelfth proposal.

“That the Philippine government withdraw from private business at an earliest possible date.”

Although this recommendation, was already accomplished by the act of the Governor General Leonard Wood, in abolishing the Philippine control board on November 10, 1926. This body where the Filipinos were in a majority control all government owned corporations including the Philippine National Bank, Manila Railroad Company, National Development Company, National Coal Company and other corporations. Governor General Wood will now be able to transfer these Philippine owned corporations into the hands of Wall Street.

11. THE AMERICAN RUBBER INDUSTRY.

America being the world’s largest consumer of raw rubber is naturally the world’s largest producer of rubber goods. Not only is the United States rubber industry the world’s largest, but it is also, one of our most important national industrial enterprises. In 1923 were registered 529 establishments producing rubber products, of a total value of $958,517,034, employing 137,868 wage earners. In 1925, 150 establishments were producing automobile tires consuming 330,000 tons of rubber as against 268,446 tons in 1924, an increase of nearly 14 per cent. In the tire production 120,000 factory workers were employed. The largest rubber producing center in the United States is Akron, Ohio, known as the “rubber city”. Then comes the rubber shoe and boot industry. In 1925, were registered 25 establishments producing boots and shoes in the United States. The number of wage earners employed was 24,999. The total value of the product produced in 1925, was $115,934,854.

Besides the production for the home market, the United States does a great export business. The export of products in 1925 amounted to $51,343,898. In addition to the large rubber industry in the United States, American capital controls the rubber industry of Canada. In 1924, Canada produced $57,411,446 worth of rubber manufactures. Of the principal 28 rubber factories in the Dominion of Canada, 18 are owned and operated by American capital as subsidiaries of American rubber concerns. The 18 factories produced 75 per cent of the total amount of rubber goods manufactured in the Dominion of Canada.

The rubber industry here is highly concentrated. These who practically control the industry are the “Big Five”: The United States Rubber Co., Goodyear Rubber Co., Goodrich Rubber Co., Firestone Rubber & Tire Co. and Fisk Rubber Co. The combined business of the “Big Five” for the year 1925 was $712,681,748 with a net profit after payment of taxes and preferred dividends, but before common dividends of $70,027,379.

12. LABOR CONDITIONS IN THE UNITED STATES RUBBER INDUSTRY.

The wages of the American rubber workers do not demonstrate that the workers share in the present day American prosperity. According to the census of manufacturers of 1923 the average yearly wage earned by an American rubber worker is $1,321 or $25 per week. The average for women workers in 1924 was $16.09 per week. This is a general view of the conditions of the rubber workers. The United States Department of Labor made an investigation on the industrial poisons used in the rubber industry, the following was revealed through that investigation.

In the rubber industry of the United States are employed a great number of women and girls. In the manufacture of small articles and footwear the women workers form 50 per cent to 60 per cent of the force. In the manufacture of tires the majority of workers are men, with a great number of young boys. The men and women employed in the rubber industry are for the most part unskilled and a great number of them are of foreign birth. With the exception of certain crafts the workers earn their wages on the piece work rate.

Regarding the conditions of the rubber workers the following is reported:

“The working day is usually ten hours, sometimes twelve hours. The night shift is 12 to 12% hours. In rare instances there are three shifts of 8 hours each.” (U.S. Department of Labor Statistics Bulletin No. 179. Industrial Poisons Used in the Rubber Industry.)

Now regarding the sanitary conditions and health protection.

“American rubber factories, even those who are in other respects admirably constructed and managed, are almost without exception lacking the proper protection of workmen against poisons. In consequence the industry is much unhealthful in this country than need to be.” (I.B.I.D., p. 5.)

Although this investigation was made in 1915 the conditions of the American rubber workers has not changed. In the first six months of 1924, 1602 accidents occurred in the rubber industry. The employers of the large factories in Akron have established sick and death benefit societies, other aid organizations, quarter of a century service pin clubs, branches of the Y.M.C.A., sports’ clubs and other schemes of Company unionism. Some plants like the Goodyear, Goodrich, Firestone have established plans and profit sharing through stock ownership. All this is a substitute for real trade unions and a decent living wage. As stated by the employers the purpose of the pension and stock ownership is to obtain efficient service. The employee owned stock in the United States Rubber Co. amounts to $6,521,935 while the total assets of the company are $322,955,786.61.

13. ANGLO-AMERICAN RELATIONS AND THE RUBBER CONFLICT

The Stevenson Restriction Act aroused great indignation among the American rubber manufacturers. Official protest was made by the United States government. A wide publicity campaign was launched through the country. Public opinion was aroused on the charge, that the British producers demand exorbitant profits from the American consumers. That the American automobiles will soon be found useless for the lack of rubber tires, etc., etc. The one to champion the cause of the American Rubber Trust was Mr. Hoover, secretary of the United States Department of Commerce. As a matter of fact it was not the American Rubber manufacturers who suffered from the high price of raw rubber. At least their increased profits do not show that. The increased price of rubber tires and all other rubber articles followed in proportion to, and in some cases exceeded the increased price of raw rubber. Four reasons can explain the rubber alarm raised in this country by the rubber trust.

1. In case of war with Great Britain the United States will be cut from its rubber supplies.

2. The desire of the American Rubber manufacturers to grow their own rubber under the American flag or in countries where investments would be safe.

3. Secretary Hoover’s political motives.

4. The possibility for Great Britain for repaying her war debts from the profits of high priced rubber.

The first are undisputable facts. It shows that America and England will not for long remain on good terms. The ambitions of Mr. Hoover for the next presidential elections are very well known. The pretext for protecting the American rubber users against the British foreign monopoly as well as against the other foreign monopolies on raw materials widely «sed in the United States, will add greatly to the popularity of the commerce secretary.

It was charged by the investigation of the Interstate Commerce Commission that the United States overpaid $300,000,000 for the rubber used in 1925. To break the British and all other foreign monopolies the American Bankers will withhold loans to these countries.

The high tariff wall that was created by the United States against foreign made commodities is also charged as a kind of restriction act against the industries of foreign countries. It was worthwhile to recall the fact, that the same Washington officials who now denounce the voluntary restriction of rubber output in the British possessions were endeavoring in 1922 to force the Cuban sugar planters to curtail production in order that the domestic beet and cane growers might exact higher prices. At the time when this article is written the Southern Bankers’ Federation recommends the restriction of the cotton acreage in all parts of the cotton belt, to prevent the decline in the price of cotton, which was resulted from the great cotton crop. The restriction of production is not only prescribed to Great Britain it is a common characteristic of all capitalist monopolies and trustification of industry.

14. THE PRICES OF RUBBER AND THE STEVENSON RESTRICTION ACT.

At the beginning we emphasized the difference of rubber from all other important raw materials in respect to production, profit yielding, etc.…There is yet another characteristic of rubber not possessed by any other raw material. This is the price.

In the last decade simultaneously with the increased production and consumption of the important raw materials followed the increased price of these raw materials. The reverse was in the case of rubber. While commodities as a whole advanced from an index of 100 in 1913 to 242 in 1920 the price of rubber dropped from the index of 100 to 41.

To illustrate this fact more clearly we will compare the price with oil, in as much as the increased consumption and production of both is due to a common factor.

The reason for this is found in the fact that up to 1913 rubber production was not really an industry. Rubber gathering was more an adventure. And the price of it was not determined by any economic factor. The average price of rubber during the war years was 58c per pound. Such prices brought great returns.

The period of high prices was followed by a great expansion of rubber plantations in the Dutch East Indies and the British producing territories. As a result of overproduction and because of the after war crisis in the capitalist economic machine the price of rubber declined to 22c in 1922. This was a threat to the British plantation owners. His Majesty’s Government, therefore appointed a commission to help to save the industry. A plan was adopted by the Colonial Office (known as the Stevenson Plan) which restricted the export of rubber. The provisions of the plan were as follows: Rubber exported from the territories under the British Flag in excess of 60 per cent based on the production of 1920 will be taxed on a gradual basis up to 24c per pound. Rubber exported under 60 per cent will be taxed 4c per pound. The purpose of this export restriction according to the British Government is to keep the price of rubber at 30c to 36c per pound. The true fact was that during some periods in 1925 the price was $1.10 per pound. At present the restriction is lowered to 80 per cent of the 1920 production.

15. PROFITS IN THE RUBBER INDUSTRY.

According to Harvey Firestone, the rubber industry is the best paying enterprise. The returns of the various rubber companies demonstrate that the dividends paid are as high as in steel, oil and other well paying industries. The profits in the rubber industry are classified into two categories.

1. Profits from the rubber plantations.

2. Profits from the rubber manufacturing concerns.

The average price of rubber during the three years of existence of the restriction act, was 32¢ per pound. The periodically increased price of the raw product reflected itself on the increased price of tires and other rubber goods at a rate of 60 to 65 per cent. The cost of production of raw rubber varies with the different territories. A pound of rubber produced in Ceylon costs 13.4c, in Malay 15.1c, in the Dutch East Indies 17.4c, in Borneo 16.5c. The selling price of rubber price on the New York market today is 44c per pound. pound.

Beginning with 1909 the annual profits of the plantation owners over a period of 14 years was 26 per cent on the issued capital. During that period the issued capital was earned three and half times. For the year 1925 the Malay planters declared a dividend of 50 per cent. The British Rubber companies according to the London Financier paid an average yearly dividend of 200 per cent for the period of 1910-1920.

The profits of the American Rubber companies are of the same rate as of the British plantation owners, of which we can be convinced the yearly reports of the leading rubber concerns in the United States.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘The Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March, 1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v06n02-apr-1927-communist.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v06n03-may-1927-communist.pdf