The first in Vern Smith’s ‘Sea Power’ serial looks at the the ship in economies up to the Renaissance.

‘Sea Power–Capitalism Comes in Ships’ by Vern Smith from the Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 2 No. 6. October, 1924.

Those germs of capitalism referred to by Marx and Engels and other historical materialists as having existed long before the real reign of capital are almost all of them incubated in the holds of ships.

The ship, even the earliest ship, fulfills completely the requirements that Engels lays down as necessary in the machinery which is well enough developed to be the basis of a machine made capitalist structure of society.

In the sense in which a ship is a producer of capitalism, and in the sense in which I have used the word here, a larger structure than a one-man-power boat or canoe is meant.

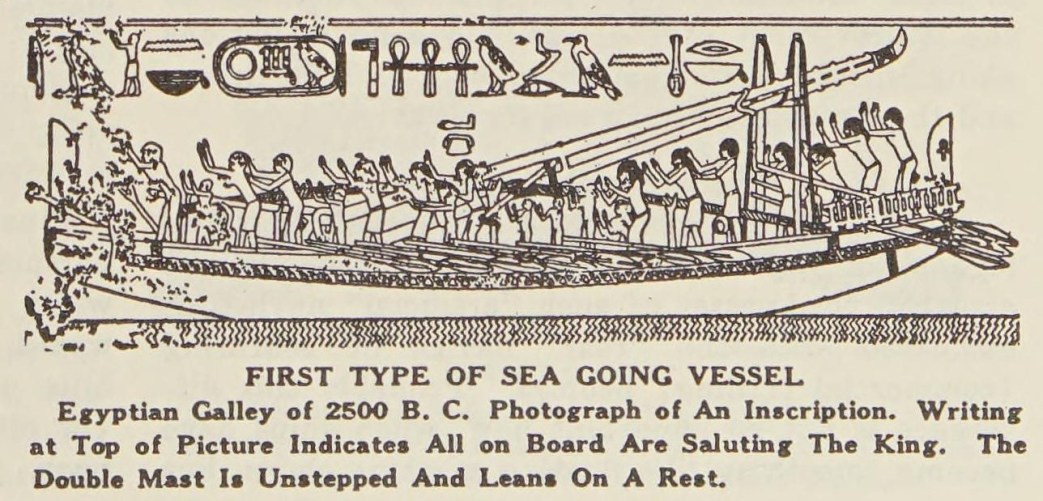

The ship as early as 3,000 B.C., was a social machine, with a crew, and a certain amount of division of labor between navigators, sailors, oarsmen, pilots, military officers, and soldiers. In this respect of requiring a crew to manage it, the men who work upon it producing none of them a personal product, but all co-operating to a common end, producing a common product, namely an ocean voyage by the whole ship, even an Egyptian galley simulated the most modern of machines for large scale manufacture. There was “social production coupled with private distribution of profit and product”—co-operation in production, with the owner of the tool, not the workers who operated it, getting the product.

Could It Have Been Better?

There is no way to tell whether, if ships had been invented during periods of primitive communism, they might not have been managed communistically, “for use and not for profit,” nor whether there might not have been ship meetings of all the workers on board, and ship committees directing all but the technical aspects of the common work, and directing the ends, even to the technical navigation, steering, etc. creeks Something of this sort exists among the joint stock junks on Chinese rivers, where the boat is divided into compartments and various merchants (some of them deckhands on the junk) store their own product in their own compartments, having each of them an even say as to the course of the voyage, the ultimate destination, etc. I do not know whether this situation improves working conditions for the merchant sailors or not, but it seems as though it should. Of course, they are still merchants, and not primarily workers, and their scheme is not much like what the class-conscious workers of today are trying to achieve. But it seems to have, like so many of the customs and social arrangements of the Chinese, an echo in it of earlier, tribal, communal life, in which classes did not count for much if they existed at all.

As a matter of fact, shipping appeared in Europe, Africa and Western Asia only after the class system was developed, after the military and the priesthood were very much in evidence as the defenders of landed aristocracy, and after division of labor and handicrafts had gone to the point where the merchant was able to function, and to make money.

The ship developed essentially as a trading instrument, a thing in which to carry goods from city to city up and down the great river of Egypt. A raft would float products of southern Egypt down to the mouth of the Nile, but something more was required to go the other way, against the current, and this meant keels, hulls, rudders, oars and sails.

The Sword Writes Its History

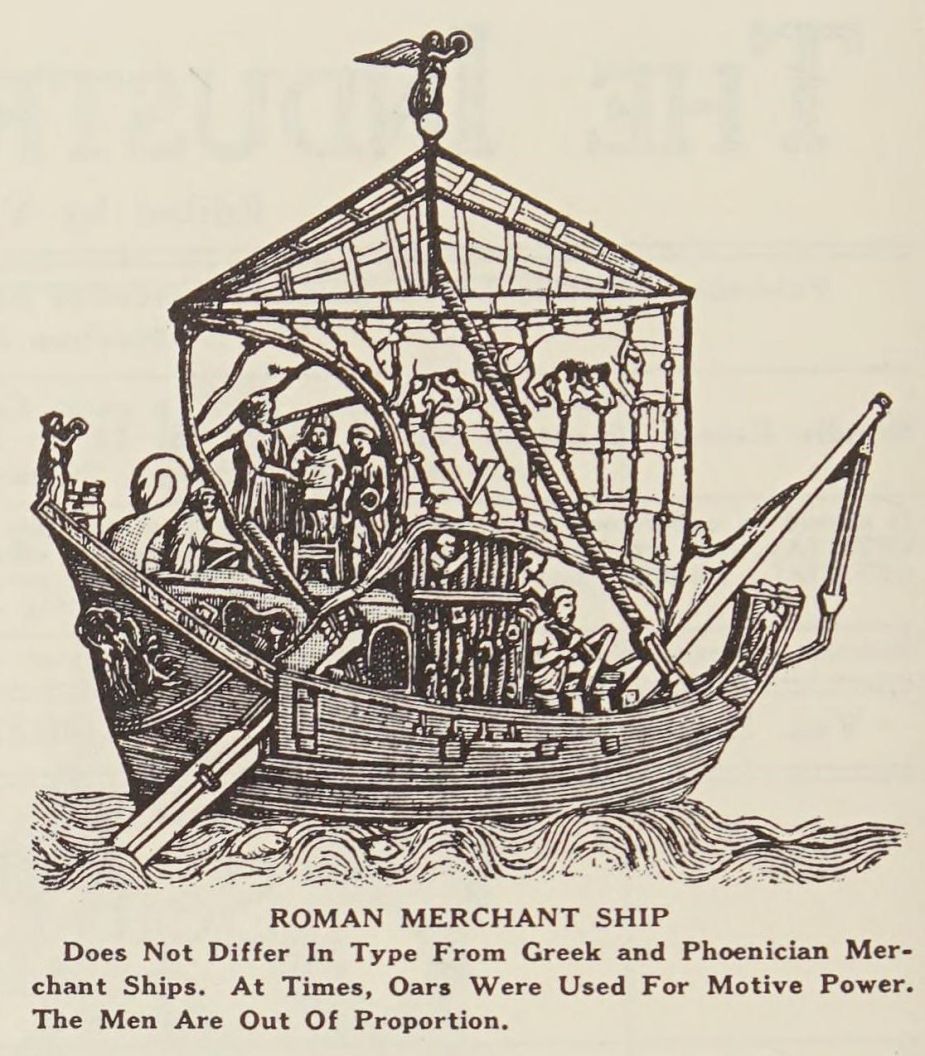

The importance of the ship for military purposes was soon discovered, and the military aspects of the ancient galley have been so overdescribed, and so much emphasized, at the expense of the peaceful commerce of the time, that one conducting research into ancient navigation would get the impression that the navies of Egypt, Phoenicia, Greece, Rome and Carthage were entirely war vessels, loaded down with nothing but oarsmen and soldiers, sitting packed like sardines, and with mighty little room for cargo.

This is an error, due to the fact that history for so long a time has been military history, and nothing more. There was plenty of merchant shipping in the ancient times, depending much more on the sail than on oars, though using man-power also, as an auxiliary force. The Greek friezes, and some of the vases (reproductions of which can be seen in the art museums) show long, narrow, many-oared war vessels in pursuit of relatively shorter, wider waisted, fewer-oared merchant ships.

Indeed, the war galley is merely a modification of the merchant ship of the period, as a study of the cargo boats of the Egyptians and Phoenicians will prove. It is interesting in this connection to observe that it was those countries which had long rivers, or short strips of sea, as their easiest means of communication which carried on and evolved shipping. It was not the most warlike nations, even those which bordered on the sea. Assyria and Persia, the most military nations of ancient times, reached the ocean, but since they were great continental powers, depending on agriculture for their sustenance, and on beasts of burden for their internal communications, they added nothing to the improvement of the ship, made no inventions along this line, and depended on the Phoenicians and the Greeks for their military navies.

Where Merchants Rule

All the authorities of the U.S. Naval War College, headed by Mahan himself, have insisted on the essential weaknesses of such “artificial”? navies, as compared with the “real” navies of seafaring (commercial trading) peoples. Probably this difference is not so important now, when ships have become something like floating machine shops, but it was important in its day, and shows that the ship is the merchant’s invention; he started it, used it, and developed a capitalist society around it. It is quite impossible to imagine the landed aristocrat taking to the water, and abandoning his fortresses and his slave agriculturists for the uncertain life of a tramp captain—and if he did such a thing, he would become a merchant of the seas, anyway. The great naval powers of antiquity were those nations in which handicrafts were fairly well developed, and which had natural harbors, or were for some reason forced to rely on water for communication between parts of their empire. Egypt and its river has been mentioned. There was China and its two big rivers. There was Phoenicia (Tyre and Sidon) with their good harbors and their position impregnable except by sea. There was Greece, a mass of islands, little peninsulas, and bad mountainous roads, except for the water ways.

Then comes Carthage, a good harbor, with a narrow strip of fertile ground around it, and nothing but desert back of that. Of course the Carthaginians were a commercial people from the first, being a colony of the Phoenicians. The practice of founding colonies on the islands and distant mainlands, followed by Tyre and the Grecian states, increased the necessity of shipping, for communication and for trade, and reacted to develop the ship itself, as it went on longer and longer voyages.

Finally there are the shipping towns of the northern part of Italy, Venice, Genoa, and Pisa, which made themselves independent through their wealth, gained in shipping, and introduced banking, bills of exchange, government by the bourgeois (or citizens), class war between the rich and the poor, and other capitalistic customs, at a time (1300-1500 A.D.) when the rest of Europe was still pretty much in the feudal period.

Forms and Facts

As proof of the fact that the ship and societies founded on sea-borne commerce are capitalistic, even in a world still largely aristocratic or feudal, it is only necessary to consider their form of government.

It is obvious that the republican (or parliamentary—no real difference between them—) form of government is peculiarly adapted to a commercial, capitalistic people. Where votes are to be the basis of political power, money counts most, and certain arts of the politicians, remarkably like those of a salesman, count secondly. This gives the men with money, especially if they be at the same time business men used to clinching bargains, the real rule of the country; whereas, if birth counted most, and military prowess counted secondly, as in a monarchy or despotism, the possession of money would not necessarily be of immediate advantage in the securing of political power.

Aristocracy and despotism in general are therefore the typical forms of government of landlord states, and republics and parliamentary governments are the typical forms of capitalistic states, even as democracies, the assemblies of the whole people, are the typical forms of government of primitive communities, or tribes.

Now which are the great republics of history? Modern western Europe and American states, of course, are either republican or parliamentary in form, since all are capitalistic. The only exceptions are the military despotisms of the Fascisti, etc., and that is something else, the breakdown of the state apparatus of capitalism, its decay.

Of the feudal states none were republican or parliamentary except just those Italian cities we have mentioned as sea-powers. There were also some German city states, sea-powers themselves in a small way or given over to manufacturing commodities for sea-trading.

Of the older states, Rome, the Macedonian Empire, Assyria, Persia, the Eastern Asiatic states, all these were aristocratic, agricultural empires— none was republican, except that Rome preserved some of the forms of republicanism from primitive communism through her traders’ wars with Carthage, and gave them up when she turned to an agricultural empire.

On the other hand, Carthage, the Greek colonies (independent), the Greek cities, and Phoenicia were all part of the time or all of the time republics, which shows that the capitalist class, the merchants especially, were a strong influence.

Two Phases of Renaissance

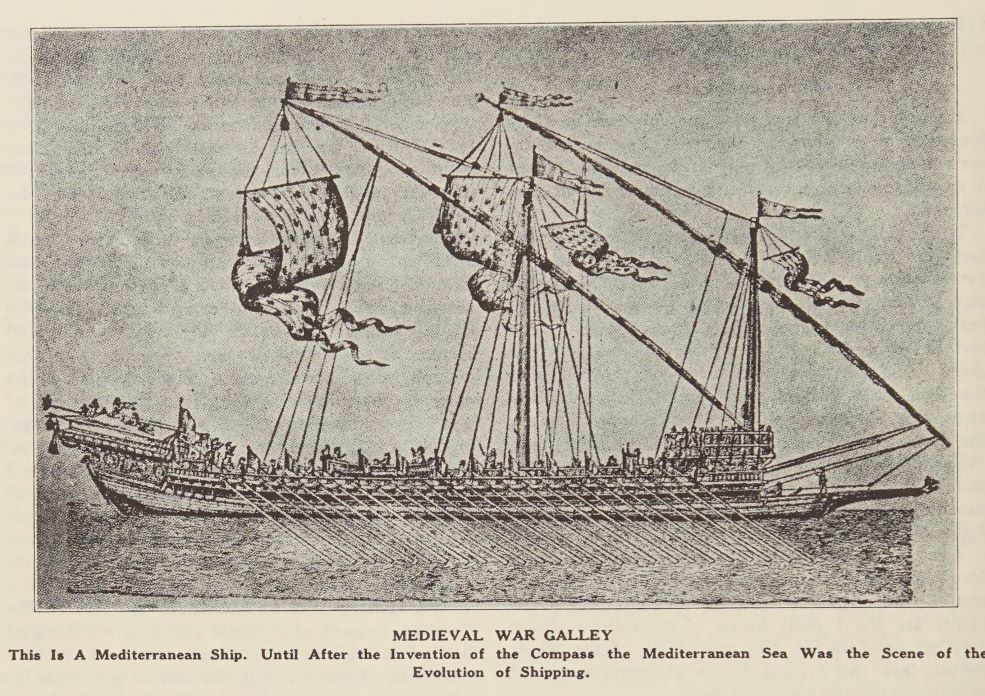

Let us now return to the later middle ages, the period of the renaissance. It is well to be explicit about this renaissance, for there were two phases, the first not much recognized, not as much as it deserves to be. Everybody knows about the second period, the magnificent outburst of art and letters, of scientific discovery and exploration. That second period was about 1400 to 1500 A. D. But there was an earlier renaissance, which caused the second. It was the revival of invention, as a social force. In fact, it was certain inventions, useful to shipping, and especially useful to navigation, that made the turn from the feudalism of the Teutonic peoples to modern capitalism.

The record of written history from earliest times down to the present, is a story of peoples who start as tribes, with economic classes of little importance, settle down and begin to farm, develop classes, weaken themselves militarily thereby, and succumb to some freer, fresher tribesmen, who then go through the same process. From the time of the pyramids (say 3500 B. C.) to the first glimmer of renaissance (roughly 1100 A. D.), there were no essential, primal invention. There were no new principles discovered. There was a certain amount of development, to be sure, but no single invention of a useful instrument was made to compare in its effects with the invention of the bow and arrow, fire, steam locomotion, or the electric motor. The life of the French or German or English serf in the twelfth century was so similar to the life of the Egyptian peasant of pyramid times, if we think of the tools used, and the methods employed for production of necessities, and the mental processes involved, and was so similar to the life of the intervening peasants of Babylonia, Persia, Greece and Rome, that a description of the social economy of one is almost a perfect ‘description of the social economy of any other. One had no tool and knew nothing that the others did not have and know. Agriculture was non-progressive. The land was far more conservative than the sea, though little real progress was made there, during this period.

Our Forefathers Were Failing

In the twelfth century the Teutonic class society of Europe, which had reared itself on the downtrodden remnants of the Latin class society of Rome, Gaul and Britain, was tottering into its period of decadence. It might have lasted on, slowly degenerating as the Roman Empire lasted and degenerated, for five hundred or a thousand years, but would have sooner or later collapsed before some fresh blooded swarm of, perhaps Slavs or Mongols. The Huns, a Mongolian people, seemed to be hitting it hardest about the time of the first crusades, which is about the time of that revival of invention which preceded what is usually called “The Renaissance.”

Now this first renaissance, which changed the course of history, and threw social evolution out of its rut, bringing in capitalism, as a transition stage from primitive communism to the industrial commonwealth of the future, was chiefly due to the ship. In order to explain just how and why, it is necessary to take a brief glance at the evolution of the ship itself.

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.