The head of the Red International of Labour Unions reviews eight years of the impact of the Russian Revolution on the workers’ movement.

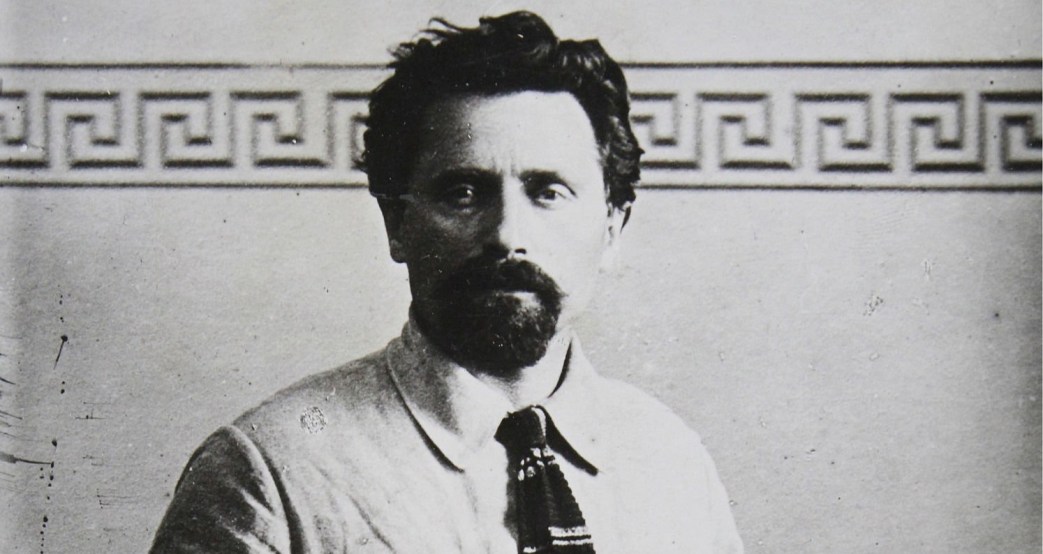

‘The International Labour Movement and the October Revolution (1917-1925)’ by A. Losovski from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 5 No. 78. November 3, 1925.

Not more than eight years have passed since the working class of Russia took the power into its own hands. Eight years is a short time, nevertheless in this period as much has happened as would suffice for centuries of so-called peaceful evolution. We must bear in mind that the October revolution took place at the very height of the war. At that time it was not clear which side would be victorious. The war reached its highest tension and, regardless of the enormous losses, the great majority of workers engaged in the Labour movement in the countries at war, was held in bondage by war ideology and the new doctrine of patriotism.

The fresh wind of the February revolution penetrated the atmosphere of the embittered war of the seething cauldron of nationalism and of the extreme degeneration of the leading centre of the socialist parties and trade unions. Even the February revolution stimulated hopes among the broad masses of workers in all countries.

This revolution is the beginning of the end of the war. The more however the February revolution, under the leadership of the Mensheviki and the social revolutionaries, assumed an Entente aspect, the more it continued to juggle with the same phrases with which in Europe the “defenders of civilisation”, Briand, Lloyd George, Henderson, Thomas and others juggled, the more keen grew the interest of the broad masses of the workers in the revolution. The socialists of the Entente Powers tried to send a special delegation to Russia in order to “persuade” the Russian revolution to fulfil the military and financial responsibilities which the Czarist regime had undertaken. The ray of peace which had shone forth, was once more extinguished, for the February revolution which had platonically pronounced itself in favour of peace without annexations and contributions, actually continued the foreign policy of Nicholas II. and his Prime Minister Stürmer.

The autumn of 1917 was very hard on all fronts. This was what caused the October revolution to break out, and its slogans: Peace, Control by the Workers, the land for the people, formed the starting point of the development of not only the revolutionary but also the political and trade union movement of the whole world.

As is well known, the October revolution did not meet with an equal reception from the workers of the different countries at war. The social patriots of the Central Powers endeavoured to make use of the October revolution to forward the interests of their imperialist State, whilst the leaders of the Labour movement in the Entente countries raised such a hue and cry against the October revolution because they anticipated that it would weaken the military strength of their countries.

But this social patriotic estimation of the October revolution could not be understood by the broad masses of the workers. In this revolution they instinctively recognised something akin to themselves and, regardless of the unprecedented agitation against Soviet Russia in the first months after October, regardless of the flood of lies and calumnies which were unexampled in their shamelessness, the broad masses of the workers had an understanding for the revolution and especially for the peace policy of the newly formed Soviet State.

The masses did not know what was actually happening in Soviet Russia, they knew no details, but, in the measure that the whole bourgeoisie and the imperialist Press hurled thunderbolts at the revolution and reported on our crimes (seizure of the banks, factories, works and of the land, shooting down of members of the bourgeoisie and of officers of high rank etc.), the interest of the working masses in our “crimes”, began to grow. This was so far no conscious acceptance of the tasks and aims of the revolution, it was merely the class instinct which led the masses of workers to support those who were so decidedly opposed to the bourgeoisie.

The October revolution forced the international Labour movement to take up a definite attitude for or against revolution by force, for or against the dictatorship of the proletariat and, since 1917, the fight between the different tendencies within the international Labour movement has continued under the banner of the fight for or against Soviet Russia. It was just this question which caused an opposition to be formed. Later on the Communist Parties developed out of this opposition, and the struggle in the trade unions raged round the question of Soviet Russia. For or against Soviet Russia, that is the wedge which since 1917 has been driven into the Labour movement, whilst clearness, determination and firmness have grown in proportion as the Soviet Union has progressed, and a real revolutionary Labour movement has crystallised which is, ideologically and politically connected with the hegemony of the revolution, the Russian proletariat and the C.P. of Russia.

As has already been said, there were no Communist Parties in 1917. Outside Russia, Poland, Bulgaria and the Spartacus Union in Germany, there was no political Party of any great significance, which was ideologically and politically allied to Bolshevism. The October revolution however promoted the formation of these Communist Parties and, with the development of our revolution and the formation of political groups within the organised Labour movement, the practical question arose of creating an international centre for uniting all international revolutionary Labour movements. This centre was created in March 1919 in the form of the Communist International, which was made possible by the work of the Zimmerwald Left.

During the first Congress of the Comintern, Communist Parties did not exist in all countries. At that time, indistinct op- positional ideas, which had not yet ripened into conscious communism, held sway among the broad masses. The formation of the Comintern favoured the further ideological and organisatory development of the international communist movement and the intensification of the fight within the Labour movement against class collaboration.

A year after the Comintern came into being (in July 1920), the question of the unity of the whole revolutionary and trade union movement arose which resulted in the creation of the International Trade Union Council which subsequently became the Red International of Labour Unions. These two Internationals at first leaned on the creator of the October revolution, the working class of the Soviet Union. The formation of the Comintern and of the R.I.L.U. gave the signal for intensifying the ideological struggle within the Labour movement and for transforming the ideological political groups into independent Communist Parties. The revolutionary tactics adopted by the R.I.L.U. in the trade union movement served as a too! for the ideological rapprochement of all who were in favour of class war in the trade unions. The formation and development of the Comintern and of the R.I.L.U. could not have taken place without that very October revolution. Thus one of the first results of the October revolution was the creation of international, political and trade union organisations which set themselves the same tasks as the October revolution.

The connection between the international Labour movement and the October revolution can be seen from the fact that even the leaders of the reformist Labour movement were compelled, though only formally, to take the part of protecting the Russian revolution, when international imperialism threatened existence of Soviet Russia. The 2nd and the Amsterdam International did not speak against intervention because they shared in any degree the aims and tasks of the Bolshevist Party, but because the workers who belonged to their organisations, feeling instinctively their relationship with the Russian revolution, exercised on the leading elements a pressure which took the form of more or less definite or indefinite resolutions of protest.

The October revolution brought the international Labour movement practically face to face with those questions which for many decades had only been raised theoretically. Socialism, the rule of the proletariat, these questions had been discussed for decades by word of mouth and in print, but in the abstract. Debates had been carried on as to in what way the working class would pass from capitalism to socialism, what would be the character of the time of transition etc. Some theorists of the 2nd International had endeavoured to show the “way to power”. Up to then, as long as all this remained in the domain of theory, a number of theorists of the 2nd International, who afterwards became renegades, had declared themselves in favour of revolutionary methods of fighting. The most characteristic example in this respect is Kautsky, who had shown the way to power fairly correctly, but only at a time when the working class was far removed from power. When however the working class was practically faced by this question, the said theorist beat a retreat and began to work out a new theory to the effect that a period of coalition governments must lie between a capitalist and a socialist society, and that the dictatorship of the proletariat is contrary to the doctrines of Marx.

The working class had not regarded the problem of power as a practical task. The socialist party propagated the idea of the conquest of power, spoke of the transition from capitalism to socialism, but no one pictured to himself how all this was to be carried out. The October revolution faced the question of power in practice, and gave the answer as to how it could be carried out. The October revolution demonstrated that the working class cannot achieve power without the forcible overthrow of the bourgeoisie, without civil war, without an unrelenting fight for power, without harnessing all their forces, and all the talk of conquering economic and political power without a revolutionary fight is merely deceiving the masses of workers. The October revolution showed this in practice, it was an object lesson.

Has the international proletariat benefitted from this lesson? Only to a certain extent, for social democracy which, after the defeat of Germany, came into power in many countries, continued its policy of an understanding with the bourgeoisie, the policy of peaceful transition from capitalism to socialism, which led to the re-establishment of the power of the bourgeoisie and to the most violent reaction. A characteristic example in this respect is the German revolution; it brought the German bourgeoisie into power, and this led the German Republic from Scheidemann to Hindenburg. Social democracy set itself the task of maintaining the whole apparatus of the bourgeois State, of maintaining production without interruption, of coming to an understanding with the “living forces” of the old society; this whole reformist idyl however ended in the “living forces” returning to power and driving back social democracy.

The value of the two kinds of tactics can be compared from the example of German social democracy and of the C.P. of Russia. The C.P. of Russia, which seized the power, used its political power for the establishment of the economic power of the proletariat; social democracy, which succeeded to power, limited itself to mere political reforms, to the extension of so- called democracy, without touching the economic mechanism of Germany. What did this lead to? It led to the bourgeoisie, in whose hands the whole enormous economic apparatus was left, taking possession of the apparatus of State as well, i.e. bringing politics into harmony with economics.

The “practical” politicians of social democracy took for granted that the socialist party, having acquired power, should begin by establishing an equality of economic rights between the workers and the capitalists, and that it is possible to abolish class war by working out an ideal constitution. But the embittered resistance of the bourgeoisie and the class war, masked by democratic phrases, showed the international bourgeoisie that economics and politics are one indivisible whole, and that he who wished to keep his hold on political power, can only do so if he has control of all the means of power in the country in question and of all the key positions in the field of industry, finance and agriculture.

The second example which proved the correctness of the tactics of the C.P. of Russia in the October revolution, was the taking over of the government by the so-called Labour Government of Macdonald. Thanks to the interplay of the written and unwritten English constitution, MacDonald assumed the Government. His was a minority government, supported by the liberal bourgeoisie. This “Labour” Government preserved everything, down to the last tiny screw of the old imperialist mechanism of the British World Empire. This policy of defending stolen goods was called constructive socialism and was contrasted to destructive Bolshevism.

The English Labour party, for whom parliamentary order and the democratic vocabulary are a symbol of faith, have shown in practice that a power which does not overstep the limits of the bourgeois constitution is not worth a farthing. A number of social democratic governments in smaller countries (Belgium, Sweden, Denmark etc.) proved also that these governments were and are nothing but managing clerks of the ruling classes who, at the moment in question, consider it advantageous to bring the social democratic government to the fore, in order that, with the support of a certain number of the workers, it may hold the Labour movement within the bounds of the law.

Thus, in the course of eight years, both methods, the social democratic and the bolshevist have had their opportunity of showing what they are worth. The October revolution, armed with military and economic weapons, stood the test, it repulsed the attack of the Russian and the international counter-revolution. It subjected the whole economic apparatus of the country to the interests of the working masses and, at the end of eight years of revolution, Soviet Russia is striding forwards under the banner of economic progress.

The social democratic tactics have not stood this test, for everything that was built up by the social democratic leaders, led in the end to the return to power of the bourgeoisie and to further enslavement of the working masses. This parallel carrying through of two kinds of tactics and of two policies, of which one was carried out with complete bolshevist consistency and the other with complete social democratic adaptability, placed before the workers of the whole world the practical question as to which of these two kinds of tactics is better and corresponds more with the interests of the working class.

The correctness of a line of tactics is determined by the results. We have seen the results of social democratic tactics, we can also see the results of bolshevist tactics. After a period of pauperization, caused by the intensified civil war, we are wit- nesses of an enormous development of national economy, of a great advance in the economic prosperity of the broadest masses of the people. To put it briefly, we are witnesses of an enormous, actually creative development of the Soviet country. The October revolution is already beginning to reward a hundredfold the efforts which were exerted in the fight against the bourgeoisie at home and abroad.

Thus, the old European and American Labour movement has in front of its eyes, in the form of Soviet Russia, a socialist fact, which must be reckoned with. If Marx could say of the Paris Commune that its greatest merit was that it existed, the same can be said with even more justification of Soviet Russia. Soviet Russia has been in existence for eight years, and the mere fact of its existence proves the correctness of the Bolshevist policy which was the basis for the creation of a united International Communist Party and of a revolutionary Trade Union International.

This however does not exhaust the influence of the October revolution. The defeat of Czarism, followed by the defeat of the landed proprietors and the bourgeoisie, the embittered fight of the workers and peasants of the Soviet Union against world imperialism, have excited the warmest sympathies of the working classes of the colonial and semi-colonial countries. Soviet Russia has become the centre of attraction for the whole of oppressed mankind.

The national freedom movements of the Near, the Middle and the Far East, recognise in Soviet Russia their natural ally and defender. The Labour movement of all colonial and semi-colonial countries feels itself drawn to Soviet Russia, independently of the currents and tendencies within its ranks there is, in those countries, much that is not clear, much undeveloped and insufficient self-consciousness. Why and whence this sympathy? Because the October revolution has hitherto been the banner both of social and national liberation, because it has been the incarnation of all forms of the liberation of mankind from slavery. It is therefore natural that the most miserable of all the pariahs, the most oppressed layers of the oppressed peoples feel more attracted to the Soviet Union than any others. Thus, the Soviet Union has become the ideological and political centre point of all national and social efforts to obtain freedom.

Only eight years have passed altogether, but in the meantime the whole international bourgeoisie has concerned itself with nothing but the question of how to stop the growth of communism and how to render innocuous the Soviet Union which has grown so exuberantly. In 1917, war was on the tapis. The Labour parties and trade unions were a blind tool in the hands of imperialism. On the social front peace ruled, but now Communism, the communist danger, is on the agenda of all countries. In spite of a number of defeats, the self-consciousness of the working class has grown. This is what disturbs the peace of mind of statesman of all countries; even where everything was comparatively quiet until quite recently, the Communist Party has become the bogey of the ruling classes.

The position in England is most characteristic in this respect. The working class of England has, for many decades been the most conservative group of the international Labour movement. Well organised economically, it has remained extraordinarily backward in the field of political fights and of setting itself class task. And now this same English Labour movement is causing the English bourgeoisie alarm, is upsetting it because fairly strong bonds have been tied between the English and the Soviet trade unions, which bind the working class of both countries more closely every day, and all this regardless of the endeavours of the bourgeoisie and of the Right wing of the Labour movement.

Why does the working class of Soviet Russia attract the Labour movement of England? Because the Labour movement in England, which has suffered a number of serious defeats and has passed through the experience of the Macdonald Government, cannot but turn its attention to the economic success which has resulted from the free development of all the creative forces of the working masses in our country, because Soviet Russia is a telling example of how the power must be won by force. Sympathy for Soviet Russia has grown in the last year or two, because Soviet Russia itself has grown. This is a fact of which there can be absolutely no doubt.

It is only in the last few years that we have had a well developed international Communist Party, a revolutionary Trade Union International which rivals the influence of the Amsterdam International, a strong swing to the Left of the whole English Labour movement, an enormous growth of the Labour movement in all colonial and semi-colonial countries, especially in China, and violent fermentation among the masses who are faced by the practical question of a further fight for real and unmistakable power.

The October revolution carried the question of power into the masses. This is not a theory, but practice overflowing with life, not an abstract consideration of socialism but an attempt at a real, practical approach to it, this is not a threat to overthrow the bourgeoisie, it is its actual overthrow. This is not a dream of the creation of a State of our own, but the actual construction of our own State, this is a proof that the working class has become a class for itself. What else has the October revolution demonstrated? It has shown that the working class can get on without the bourgeoisie, without landed proprietors, whereas social democracy is making efforts to prove that the working class cannot exist without the bourgeoisie.

The international Labour movement has made vast progress in these eight years. From a small organisation such as was the Zimmerwald Left in 1917, it has grown into an enormous international Communist Party which causes no little trouble and anxiety to the international bourgeoisie and its social democratic allies. Only eight years have passed, but if we examine the international Labour movement more exactly, we see that it has grown older by several decades. It has grown up because it has been able to make use of the revolutionary experiences, the revolutionary work of the Russian proletariat, and to carry on the fight against its own bourgeoisie on the basis of these experiences. The October revolution is the greatest event in history. As even our enemies and those who are ideologically in other camps, admit, it is the starting point of the social world revolution, the beginning of the replacement of the capitalist system by the new socialist system. Many decades will be necessary to clear away the vast capitalist machinery which it has taken centuries to build up. The chief thing however is that the world revolution has begun and that a fairly large piece of ground has been covered. It is difficult to say how many years the international proletariat will take to reach the end of the path it has struck out for itself. The point of greatest importance is that the international Labour movement has started on this path, and that is to the immortal credit of the October revolution.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecor” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecor’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecor, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1925/v05n78-nov-03-1925-inprecor.pdf