Harrison George on the history of the exploitation of Minnesota’s massively rich Mesaba iron range, and the first general fight of workers there to unionize.

‘The Mesaba Iron Range’ by Harrison George from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 17 No. 6. December, 1916.

IN THE Chippewa tongue, “Mesaba” means “giant”; the red man having the right slant at things; as when he punctured the dignity of the early French missionaries by terming them “the men waving a stick.” The Mesaba Iron Range and everything connected with it is truly giant.

In the dim past some great glacier, grinding its way southward met with a mountain range, smoking and shaking with volcanic fires, and formed thus a low range of hills surmounting the high plateau that lies between the western horn of Lake Superior and the Canadian line. Here in the forests dwelt the Indian in comparative contentment until came the white man “waving a stick” in one hand and a “piece of paper,” called a treaty, in the other and the happiness of the red man was gone forever.

Yet over a century had gone ere the organized brigandage of the white man, embodied in the Weyerhauser Lumber Company, entered the country in true second-story style and tore out the forests. Then in 1890 it was discovered that the Mesaba Range contained the greatest iron ore deposits known, and a second set of merry highbinders rushed in to burrow under the stumps for concealed treasures.

The first lot didn’t make out very well. After finding the ore bodies the next question was transportation. A part of them banded together and built a railroad to the lake. To do so they needed money and they borrowed it from Rockefeller and mortgaged the whole works, mines and all, to John D. But they found that individual capital was too small to purchase the massive machinery for each mine and conduct a cut-throat competition at the same time. They were not convinced of this however, until John D. foreclosed and took away both mines and railroad.

In the meantime there were two other groups of mine holders grabbing things. H.W. Oliver, a millionaire friend of Carnegie, had gone in and bought to the limit of his resources. Also a third group, a job lot of speculators, had seized onto a respectable share of the known ore bodies and were sitting tight to see what would happen. They found out very soon.

While the “Laird of Skibo” went fishing on Loch Rannoch and his Pinkertons were emptying rifles into the hearts of the Homestead strikers in July, 1892, H.C. Frick, the big guy in the Carnegie Steel Company, was scheming with Oliver to corner the iron deposits of the Mesaba Range. In opposition to the express wish of Carnegie, who in this instance, as in others, demonstrated how brainy he was not, Frick forced a fortune onto Carnegie in the shape of a half interest of Oliver’s present and future holdings without costing Carnegie a red cent. In exchange for a loan of half a million to be used in development work, which loan was, of course, secured by mortgage and repaid with interest, Oliver made a present to the Carnegie Steel Company of a half interest in all his holdings in iron mines.

This done, Frick, Oliver, et. al., turned to John D., who being busy at that time with a few plans of his own for putting rival refineries on the blink, was not particularly anxious about monkeying with iron mines. They contracted with Rockefeller and secured leases on all the mines Rocky had foreclosed on, upon a basis of 25 cents per ton royalty, with the provision that in exchange for this extremely low royalty the Carnegie people were to mine and ship over John D.’s roads and in John D.’s boats not less than 1,200,000 tons of ore yearly for fifty years.

This done, that third group of “independents,” who had been sitting tight to see what would happen, hearing the news of the Carnegie-Rockefeller combine, and evidently appreciating the kindly intentions of these commercial Apaches, fell over one another to sell at any old price they could get to the Carnegie-Frick-Oliver crew, who thus gobbled control over the Mesaba Iron Range. It is worthy of note that at this time some members of the Minnesota Legislature are accused of having an itching palm–and having it scratched with some of Carnegie’s iron dollars, in exchange for a leasehold of state lands for the small royalty of 25 cents per ton, when private holders were and are getting from 50 cents to $1.00 per ton royalty.

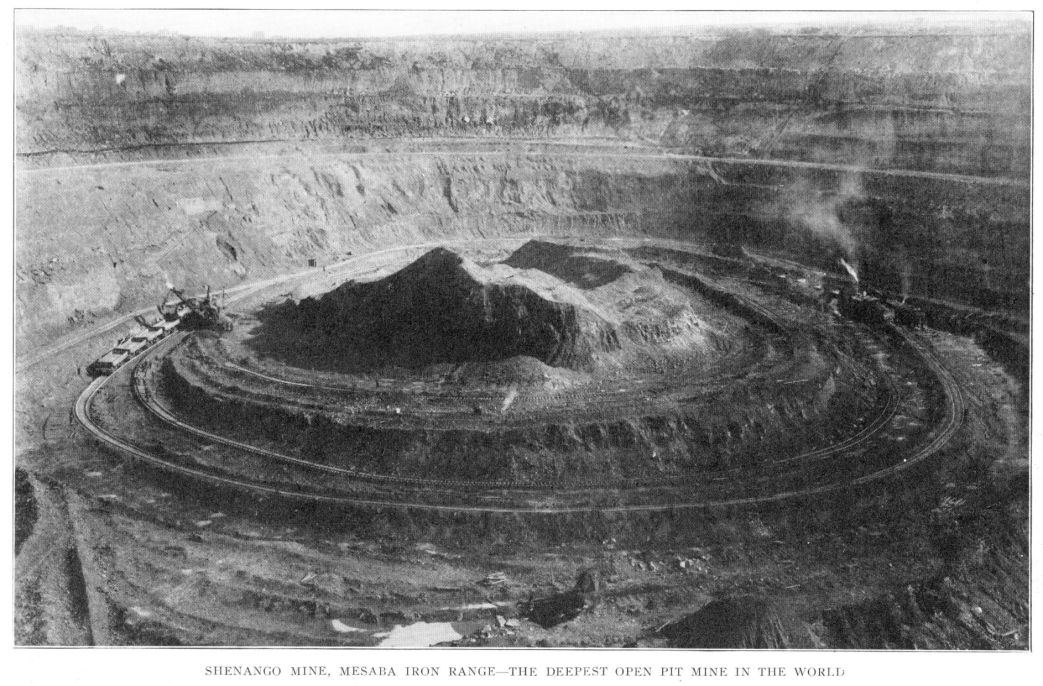

Today the Indian word, “Mesaba,” can be rightly applied to everything connected with the Range. Carnegie and Morgan combined, forming the United States Steel Corporation, a giant organization. Massive machinery was brought in and today the face of the earth bears frightful and gigantic scars. The open pit mining, which requires stripping off the surface to the ore-bed; the milling process, which leaves immense chasms from which the ore has been taken out through chutes leading to an underground railroad; all the impedimenta of vast and ceaseless activities–changing the aspects of nature. Stupendous artificial mountains of over-stripping greet the eye on every hand; great pits yawn where once was level ground; underground caverns have caved in, burying men by the score with entire trains, and there they still lie buried. The silence of the ages has been hunted out by the screaming whistles, the groaning of giant steam shovels, the snorting of innumerable locomotives–while incessant blasting rocks the body of the Range from end to end. Machinery has been invented capable of doing incredible things, and man and his labor are almost lost sight of in the immensity of operations.

Men are there however, thousands upon thousands of them, risking their lives day after day in underground drifts or taking chances at having their brains dashed out by the swift swinging buckets of the steam shovels in the open pits.

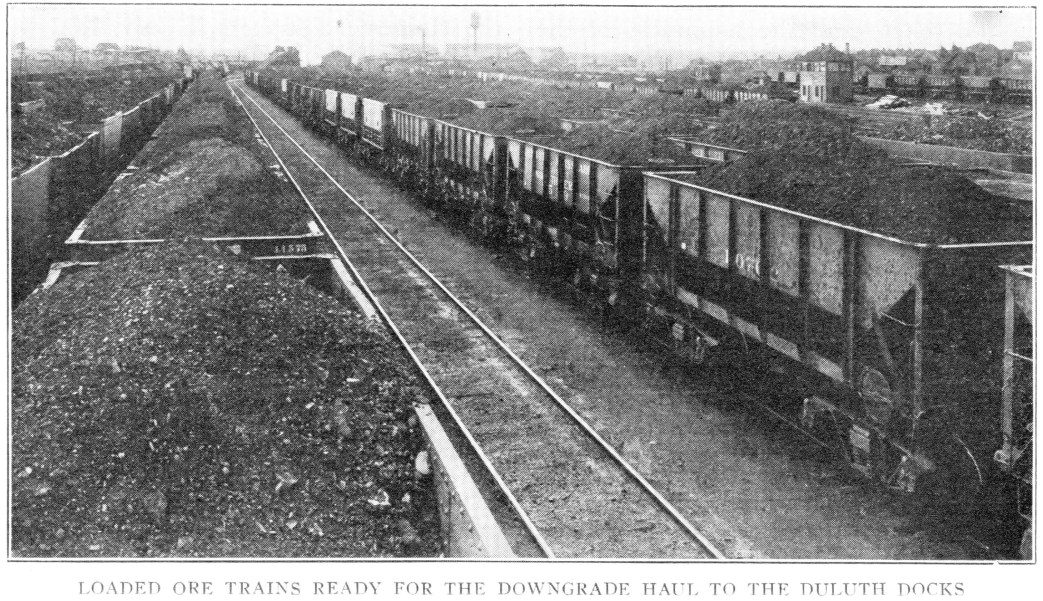

Loading the ore into hundreds of cars, making up the hundreds of trains that leave the Range every day for the trip by gravity into the hopper-holds of the ore boats at the great docks at Duluth, are men who make possible the basis of civilized life-machinery.

Divided by races and unorganized, these men were exploited to the limit by the boss of the Range, the United States Steel Corporation. The big, stolid Finns could not comprehend the longings for better conditions expressed in the purring tongue of the Slav who worked beside him; the Slav in turn knew not the meaning of the soft-voiced Italian at his elbow when he whispered curses at the boss. Every attempt at quiet organization was killed at once by company spies.

Last summer, however, things boiled over and the smoldering discontent flamed out into open industrial rebellion. Most of the readers of the REVIEW are familiar with what followed; how these divided peoples were welded into a solid fighting body by organizers of the Industrial Workers of the World; how the Italians and Austrians, finding a common cause, clasped hands of FELLOW WORKERS, pledging each other in voices choked with emotion that they would let the old country with its kings go to war or to Hell-they would stick together in the ONE BIG UNION.

The usual army of drunken slum-scum was imported and deputized. A new record was established for unjustified arrests. LAW AND ORDER, frenzied by the promptings of its master, beat up and jailed over six hundred men and women. John Alar, a striker, died a victim of Oliver gunmen. Likewise, so it is sworn, Thos. Ladvalla, an innocent bystander, died at the deliberately aimed fire of Nick Dillon, a creature whom the Mesaba Ore, a local paper, characterizes as the Steel Trust’s “pet murderer”; when Dillon and three deputies invaded the home of Phillip Masonowich.

An armored train, a la “Bull Moose Special,” of Paint Creek fame, was built in the Duluth shops. Machine guns to commit murder by wholesale were installed. The train was rushed to Hibbing under cover of darkness and there concealed in one of the Oliver pits. Steam was kept up and the band of blood-thirsty cut-throats in charge was ready at any time to swoop down in drunken glee and turn any Range town into a shambles. It is alleged that this crew, knowing they could hide behind the law, could hardly be restrained at times from issuing forth on a murder raid, “Just to see if it would work!” A truly American institution, this private army of the Steel Trust.

The frame-up by the putty officials, moulded by the iron fist of the Steel Trust, to railroad the I.W.W. organizers because of the death of James Myron, a deputy, killed by one of his own gang in the Masonovich raid, is now up for battle in the courts. How successful the Steel Trust will be in slaking its thirst for the blood of Tresca, Scarlett, Schmidt, the Montenegrin strikers, and Malitza Masonovich, depends upon the support, chiefly financial, which the workers everywhere may lend to their defense.

The significance of these trials should move all sections of the labor movement into action in their behalf. Here, so says Judge O. N. Hilton, there is to be a showdown as to whether or not the infamous Chicago Anarchist Decision shall continue to live as a legal precedent, to be used to stifle the voice of any labor leader or organizer who dares open his mouth in a strike zone. Last year, John Lawson of Colorado was convicted under this diabolical decision; today Tresca, Scarlett and Schmidt face the same fate, and, before the smoke from the battle on the wharf at Everett clears away, I suppose there will be another group of brave men facing the gallows because they cried out for Freedom. It matters not whether “get” were there or not; they will face their doom if this devilish, bewhiskered Chicago Anarchist Decision is not broken in the Minnesota trials.

Whoever you may be that reads these lines, YOU can do SOMETHING! You can, with your fellows, sweep the nation with such a tide of protest that Capital will relax its iron fangs in fear of a GENERAL STRIKE. Send protests and demands for justice to Governor J. A. Burnquist, St. Paul, Minnesota. Send funds, unstinted and at once, to James Gilday, Gilday, Secretary Treasurer Mesaba Range Strikers’ Defense Committee, Box 372, Virginia, Minnesota. Here in this small city the greatest legal battle for labor waged in this decade will begin on the fifth of December. The fate of seven men and one woman and YOUR right to organize hang upon your answer.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v17n06-dec-1916-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf