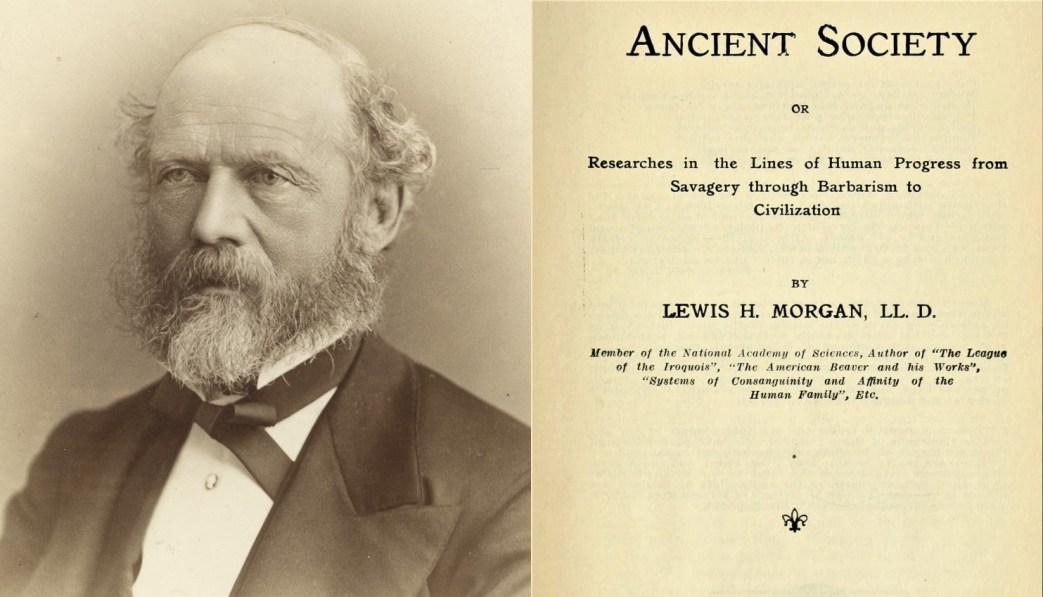

A major figure in anthropology of the first half of the twentieth century, Robert H. Lowie, with a regardful critique of the defining work by Lewis H. Morgan, the foremost anthropologist of the nineteenth century, and key reference for Engels’ ‘The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State’ and Bebel’s ‘Women in the Past, Present, and Future.’

‘Morgan’s “Ancient Society” by Robert H. Lowie from New Review. Vol. 3 No. 9. July 1, 1915.

NO ethnological work has probably reached a larger audience than Lewis H. Morgan’s Ancient Society. Historians, sociologists, economists, philosophers, have been profoundly influenced in their views of primitive life by Morgan’s theories, and the enthusiastic espousal of these doctrines by Engels and Bebel has made his name a household word in Socialistic circles.

Morgan’s services to ethnology are assuredly neither few nor slight. He combined the inestimable advantage of an intimate personal knowledge of one primitive people with a lively theoretical interest in the problems of cultural development and a keen flair for significant phenomena that had been overlooked or ignored by his predecessors. However, he wrote his most popular book in 1877 when an intensive systematic ethnographical survey of the globe had barely begun, when indeed hardly a single primitive tribe was thoroughly known in all its aspects, and when the rise of Darwinism had given an impetus to the construction of artificial evolutionary schemes. Moreover, Morgan shared with other men of markedly synthetic tendency a certain lack of sobriety and of logical rigor. Under these circumstances it is simply absurd to treat his Ancient Society as the last word in ethnology. The one-time groveling before the letter of Morgan’s teaching has indeed produced a strong reaction on the part of some recent students, who have been betrayed into quite unwarrantable contempt for his ethnological achievement. The layman who has steeped himself in Morgan’s atmosphere is thus likely to lose his bearings when he chances on some such stray gust of criticism. In the following paragraphs I hope to give some first aid to the flounderers. I will select for discussion the three points on which Morgan is most frequently quoted as an authority: (1) his general view of cultural development; (2) his conception of the one-sided kin group (“gens”); (3) his views on the development of the family. I hope to make clear in every case what are the elements of permanent value in Morgan’s treatment and what elements have become antiquated.

I.

Morgan’s least original and least valuable contribution is embodied in his scheme of ethnical periods. He divided the history of human development into three periods labeled savagery, barbarism, and civilization, respectively; and subdivided the first two into a lower, middle, and upper status. Civilization was said to begin with the use of a phonetic alphabet, and barbarism with the practice of pottery; the upper status of savagery commenced with the use of the bow and arrow, and the other divisions were defined by traits of similar type.

What first strikes us in this outline is the arbitrary character of the criteria used for grading cultures. No ethnologist would now place the Polynesians with their highly developed political communities and their extraordinary artistic ability on a lower level than the rudest North American aborigines simply because the latter used the bow and arrow and the Polynesians did not. By laying stress on arts and customs arbitrarily ignored by Morgan we should have a transvaluation of values that would very largely alter his scheme of evolution. If we chose complexity of social arrangements as a standard, the Australians, whom Morgan places in the middle status of savagery, would have to be rated far above the majority of North American tribes, who are ranked by our author in the upper status of savagery and the lower status of barbarism. Again, if we graded peoples by their skill at basketry rather than by their pottery, some of the otherwise crude Californian natives would suddenly rise to a very high rung in the scale. Judged by their knowledge of the iron technique, the African Negroes would tower immeasurably above all the aborigines of the New World, yet if we substitute architectural achievement as our guide the palm would have to be awarded to the American Indians. There are, to be sure, tribes like the Bushmen which are so obviously deficient in almost every phase of culture as to make a decided impression of inferiority, and these would be rated as culturally low by every ethnologist. But except in the roughest way no grading is possible because marked advancement in one line may be accompanied with obvious backwardness in others, and there is no way of objectively testing to which criterion we should yield precedence.

Owing to the available archæological evidence there can of course be no doubt as to the gradual development and generally increasing complexity of human culture. In this, but only in this very general sense, Morgan was right and did good pioneer service. But he was quite wrong in assuming that cultural evolution, so far as it was not checked by differences in the natural environment, must follow the same course, that the development of human institutions was predetermined, as he put it, “by the natural logic of the human mind and the necessary limitations of its powers.” Though the essential psychic unity of mankind is generally admitted, the possibilities of reacting to the same stimuli are not so narrowly limited as Morgan supposed. Nothing, for example, may seem more natural than that cattle-raisers should milk their cows and eat beef. Yet among many Asiatic tribes, the Japanese included, milking is practically tabooed, while among South African Bantu tribes milk forms a staple diet, but the meat of the cattle is only eaten on exceptional occasions.

But even if there were a strong tendency toward the production of similar cultural traits all over the globe, we have to reckon with another factor that has come to be recognized as of greater and ever greater significance during the last two decades and that obscures the tendency toward uniform development, the fact of cultural borrowing. It has been clearly shown that when alien tribes meet, cultural possessions are freely borrowed from one group to the other. This being so, we can no longer represent the history of any one tribe by a single line purporting to represent a law of cultural growth. If such a tribe should practise the arts of weaving and pottery, for example, the latter may have been introduced from the outside and then we should have no right to say that the tribe had risen to the pottery stage, i.e., to Morgan’s lower status of barbarism, by some inherent necessity. We cannot say with any degree of assurance, to turn to another example, that Japan would have developed European civilization if that civilization had not been impressed upon her from without. Whether she would, is a question for the metaphysician rather than the scientist. The ethnologist can only state the fact that all the cultures he studies show evidence of complex origin. This being so, he must in the first place analyze them into their constituents. But, whether a certain people adopt a certain trait from another or not, is in large measure a matter of historical accident, and there seems little prospect of discovering a general law for the innumerable complications that have resulted from accidents of this sort. Accordingly, ethnology has turned aside from the attempt to outline a general scheme of evolution along a single line and seeks instead to reconstruct for every area and tribe its individual history of development.

II.

By a “gens” Morgan understood a social unit composed of a supposed female ancestor and her children, together with the children of her female descendants through females; or of a male ancestor and his children, together with the children of his male descendants through males. In America the term “gens” is now generally restricted to the second type of social unit with patrilineal descent, while a social unit with maternal descent is called a “clan.” I will adopt this usage, referring to both clans and gentes as “one-sided kin groups.”

Morgan assumed that the human race passed through a stage when brothers and sisters intermarried in a group. At a somewhat higher level, he argued, such marriages were prevented by organizing society into kin groups of the type defined above and absolutely prohibiting marriage within the groups, i.e., making them exogamous. In other words, Morgan held that the restrictions on what we consider incestuous marriage came in with the one-sided kin group and did not exist at a certain cultural stage of earlier date.

It is impossible even to indicate here all the relevant problems. Suffice it to say that Morgan (1) assumed that the clan preceded the gens because in the early days of society fatherhood was uncertain and descent could be traced only through the mother; kin group and (2) regarded the one-sided exogamous (except in Polynesia, where he merely noted a rudimentary foreshadowing of this unit) as a well-nigh universal institution of human society. To these two points I must at present confine myself.

In regard to the first problem it cannot be said that Morgan’s view is antiquated since it is still shared by a great many sociologists and ethnologists. Nevertheless, even adherents of this doctrine now make an important distinction. They still hold that a gens never develops into a clan while there is good evidence of the reverse change; but they no longer insist that every gens must have developed out of an earlier clan. Indeed, there is not the faintest empirical proof that certain tribes in North America which reckon descent through the father ever traced descent in the matrilineal way. Accordingly, American ethnologists such as Swanton, Goldenweiser, and the present writer, deny that Morgan’s sequence rep- resents a universal law of development. In fairness it should be stated that most students of Australia continue to regard the clan organization as more primitive than that based on paternal descent and that Rivers makes the same assumption for Melanesia. The belief in the necessary priority of the clan, however, has been seriously shaken.

An even more important question relates to the practical universality of the exogamous kin group at an early stage of civilization. Here again the North American data are especially significant, for among the Indians it is precisely the tribes of crudest culture, the natives of California, the Plateau, and Mackenzie River areas, that lack any trace of the clan or gens while most of the agricultural peoples with highly complex ceremonial activities, such as the Iroquois, Southern Siouan, and Pueblo Indians, also possess a clan or gentile organization. In other parts of the globe there are likewise very backward tribes, for example in New Guinea, among which the exogamous unit has never been observed.

These facts may be fitted into Morgan’s scheme by either one of two hypotheses. It may be assumed that the tribes now lacking exogamous divisions formerly had them but lost the organization. However, this is a purely gratuitous supposition, without the slightest evidence and rendered in the highest degree improbable by the large number of cases that form an exception to Morgan’s rule. Secondly, these exceptional cases may be conceived as representing a cultural stage antedating the institution of clans. But on this theory they ought to represent the greatest looseness of marital relations among blood-relatives, while as a matter of fact in each and every one of the tribes in question there are very definite rules against the marriage of closely related kin. Accordingly the facts cannot be squared with Morgan’s theory. Tribes of a crude culture exist which have no clans or gentes, yet they are not so low as to lack stringent rules against incestuous unions.

This last-mentioned fact indicates a fatal narrowness in Morgan’s view of primitive society. Morgan’s was a distinctly monistic type of mind. He naturally tended to conceive all social units of primitive tribes as genetically connected with the exogamous kin group. Thus, he regarded the Australian classes as incipient clans and the moieties or phratries of North America as merely overgrown and sub-divided exogamous units. Today we view the Australian class-system as an institution sui generis; and we should regard it as possible that moiety (or phratry) and clan or gens were in a number of cases of distinct origin. Moreover, restrictions on marriage occurring where there are no clans or gentes prove the existence of some sort of family concept distinct from the notion of exogamous kin groups, while among the Indians of the North Pacific coast a caste system is found coexisting with exogamous kin groups. Instead of all primitive society being modeled on the one clan pattern, we thus find a much greater variety than Morgan allowed for in his account of primitive social organization.

III.

Morgan’s speculations on the evolution of the family have aroused the hottest criticism, yet they are connected with one of the most notable achievements in the history of ethnology, his discovery of the classificatory system of relationship. Having noted the fact that the Iroquois terms for “father,” “mother,” etc., do not designate single individuals but whole classes of individuals, such as all the father’s brothers and all the mother’s sisters as well as the father and mother respectively, Morgan afterwards found that this was not a peculiarity confined to the Iroquois but shared by many North American tribes. Through indefatigable study and correspondence he established the fact that this classificatory system also occurs in Africa, India, Australia, and Oceania. The wide distribution of this form of kinship nomenclature among wholly unrelated peoples remains one of the basic facts of comparative sociology.

Among classificatory systems Morgan recognized two types. In those of Hawaii and other Polynesian groups, which were simpler and therefore seemed more ancient, no distinction was drawn between the father, the father’s brother and the mother’s brother; nor between the mother, the mother’s sister and the father’s sister. and the father’s sister. In the systems of North America and India no distinction was drawn between father and father’s brother, or between mother and mother’s sister, but the mother’s brother was sharply distinguished from the father, and the father’s sister from the mother, through the use of additional terms. Morgan concluded that the Polynesian system was a relic of the hypothetical custom of brother-sister marriage; the Hawaiians, for example, called their father’s sister “mother” because at one time a man had exercised marital rights over his sister. In the North American and Indian systems he saw the effect of restrictions on this primitive looseness: when a man no longer cohabited with his sister, his children ceased to class her with the mother; on the other hand, the father’s brothers remained “fathers” since they continued to share one another’s wives.

Lack of space prevents adequate treatment of this most abstruse of ethnological topics; I can only state a few of the results without entering into the course of the argument. In the first place, Rivers has furnished good evidence for the view that the Hawaiian nomenclature was not primitive but arose through later simplification of a terminology of the more complex North American type. Corroborative testimony from Siberia has been supplied by Sternberg. Secondly, it does not follow necessarily that individuals must have shared wives because they are designated by the same term: this term may simply designate the status of a man, his marital potentialities. If, for example, a tribe is divided into exogamous moieties, the fact that a person calls his father’s brother “father” may simply mean that there is one term in the language to denote any male member of moiety A and the generation of the speaker’s mother. It may denote that the person addressed might marry the speaker’s mother without infringing the exogamous rule, but not that he actually has access to her.

In the most general aspect of the question, however, Morgan was right. Though his particular inferences from kinship terminologies are largely mistaken, the principle that these nomenclatures are connected with social phenomena of some sort, that they are not merely capricious creations of human psychology, is sound. It has only recently been proved from Oceanian material by Rivers, who shows that the classificatory system is probably connected with exogamy, a theory already suggested by Tylor and even gropingly divined by Morgan himself. I have satisfied myself that this theory holds for North America, that there is in other words a correlation between the classificatory kinship systems and exogamous divisions. Morgan thus deserves credit not merely for having unearthed a recondite cultural trait and established its distribution, but also for seeing that this trait was a matter of sociological importance. The precise extent to which the systems of kinship reflect sociological condition is a moot-question. Rivers regards all elements of kinship terminology as sociologically determined, Kroeber once denied any such connection but is said to have altered his views in the light of Rivers’ recent investigations, though his change of mind has not yet found printed expression. I incline to the golden middle course, holding that many terminological features are determined by social causes, such as forms of marriage, while others must be accepted as simply psychologico-linguistic products lacking a sociological foundation.

IV.

It must be clear from the foregoing remarks that this is not an attempt to depreciate Morgan’s achievement. His Ancient Society remains a landmark in the history of ethnology, but it is a work that can nowadays be most profitably read by the specialist. The layman is likely to derive very wrong notions from it, just as he would get a very imperfect conception of modern views of evolution or heredity from Darwin’s Origin of Species. In the absence of good, popular, up-to-date books on ethnology the general reader must be referred to special papers. I suggest the following for those interested in the problems of exogamy and kinship systems: Heinrich Cunow, “Zur Urgeschichte der Ehe und der Familie” (Ergänzungshefte zur Neuen Zeit, No. 14); W. H. R. Rivers, Kinship and Social Organisation (London, 1914); A. A. Goldenweiser, “The Social Organization of the Indians of North America” (Journal of American Folk-Lore, 1914, pp. 411- 436); Robert H. Lowie, “Social Organization” (The American Journal of Sociology, 1914, pp. 68-97). The modern point of view in regard to cultural stages is presented in Boas’s The Mind of Primitive Man (New York, 1911, pp. 174-196).

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1915/v3n09-jul-01-1915.pdf