‘The Class War Within the Arab National Movement’ by Joseph Berger from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 4 No. 32. June 5, 1924.

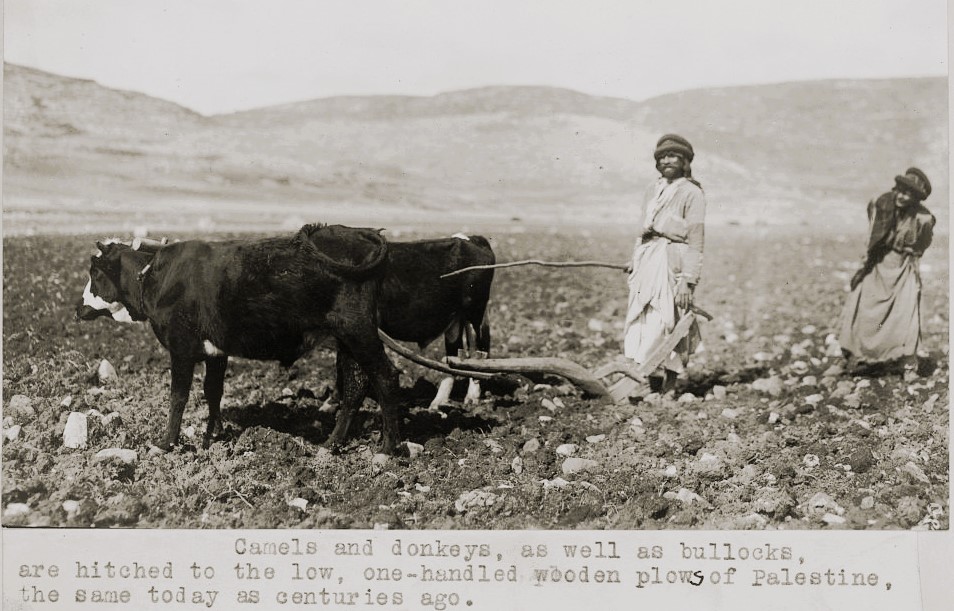

The Arab national movement in the countries of the near East (Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine, Transjordania) is still very young as a people’s movement. Before the war it was only a few groups (families) among the rich landowners (Effendis) who took any part in politics. These feudal landowners, who own by far the greater part of the ground which they let to poor tenants (Fellahin), usually for return of half of the produce of the land which is invariably very scanty, were able to carry on undisturbed this exploitation under Turkish rule and had at most to yield up but a small part of their profits as taxes to the corrupt Turkish officials. Now and then there were struggles for power between the various feudal families, which, according to whether the government was on their side or on the side of their opponents, were either pro- or anti-Turkish. The people, that is the mass of the towns and villages, had settled down in the course of decades and centuries to this condition of affairs and dragged the chains of feudal exploitation almost without a murmur, while they only came into conflict with the foreign ruler, when he wished to increase the taxes or press the peasants’ sons. into military service.

The war with one blow ended this “idyllic” state of affairs. One section of the aristocratic families formed an alliance with the Entente powers in return for the promise of a “national” government, in which these families were to have the greatest influence. But after the countries had once come into the possession of the imperialistic powers, the latter did not keep these promises. They certainly allowed the Effendis to carry on their exploitation of the Fellahin; it was further increased, but the new government began itself to collect the taxes, which it used to farm out to the Effendis, and deprived the Effendis of a great part of their income in favour of its own apparatus.

On the other hand, the Fellahin were also shaken up by the war. The war brought with it devastation and starvation, forceful requisitions and the destruction of whole villages. The English government of liberation did nothing to put agriculture upon its feet; it only knew how to raise taxes. Similarly with the town-dwellers: European domination did not open up the way to prosperity, but at every step brought strangulation, oppression, crisis, impoverishment. This all led to the Arab movement developing in a few years after the war into a people’s movement. Neither the hangmen of the bloodhound Gourand in Syria, nor the bombs in Mesopotamia, nor the intriguing diplomacy of Herbert Samuel in Palestine could prevent that. The Arab population unanimously declined the foreign mandates. The protests which the official National Party handed in to the League of Nations and to all the powers, were without doubt the real expression of the deep resentment of the people against the foreign tyrants.

Still, however unified the Arab movement may appear from without, it carried within it the seed of the contradictions, which represent the heterogeneous elements, of which it consisted, and which sooner or later must come to open outbreak. The three chief elements of the Arab National Movement are:

1. The feudal landowners; 2. the town elements with a tendency towards capitalism; 3. the peasantry and town workers, upon which the first two elements are supported. During the last few months it came to an important difference between the first two elements. The fighting methods of the Effendis against the Foreign Governments had disappointed the whole of the people, they remained unsuccessful. The Effendis, as leaders of the National movement, had fought not for the liberation of the people, but simply and solely for their own interest, and could bring themselves agree in principle with all compromises with England and France, if only influence and concessions were granted them in return. Their fight was limited to protests, journeys with petitions and requests to the various European capitals and places where conferences were held.

Now it is the town bourgeoisie which, exploiting the disappointment of the wide masses in their old leaders, wishes to take the matter in hand. The new Arab “National Party”, which consists chiefly of intellectuals, merchants etc., has begun its activity with a campaign, aimed at discrediting the official leaders. Charges of treason, corruption and incapacity are made against them. While the “old” party sticks fast to a few stereotyped forms of protest, the new party wishes to carry on real politics and is setting up a whole series of demands for reform in social economic and questions (especially agrarian reform). The old party, in whose hands are the traditions and the religious authority which is of great importance in the Orient, has answered the rise of the new party by the sharpest opposition against it, it has been placed under a religious ban and called “a brood of traitors”, charged with splitting Arabian unity, and in fact the leaders, as happened in the ceremonies in Amman (Transjordania) are subjected to attacks and acts of terror. The new party, which still unites quite different classes, is in spite of its weakness at the present moment, in a position, in the not too distant future, to play a role in the countries of the near East such as Zaghlul Pasha played in Egypt.

Among the progressive elements of the Arab national movement, there is widespread sympathy, not only for the “national hero” Mustapha Kemal and his newly formed Turkey, but for anti-imperialist Soviet Russia. It is only to be ascribed to the strict illegality of the C.P. that the leaders of the new party do not seek direct connection with it. The working class element, however, particularly where it has anything directly to do with the organs of imperialism, like the workers on public works, railwaymen etc., is more revolutionarily inclined than any of the existing national parties. Here a work of communist enlightenment which, beside the national element, would place the social element in the foreground, would have great prospects of success. It depends on the means and possibilities of the Sections of the Communist International in the Orient, whether the next differentiation in the Arab national movement is to be the passing over of the proletarian elements into the ranks of the Communist movement, which would mean a continuation of the process, which began with the splitting off of the bourgeois elements from the earlier uniform party. Only then would the struggle against imperialism assume really revolutionary forms and be able to promise speedy results.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecor” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecor’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecor, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1924/v04n32-jun-05-1924-inprecor.pdf