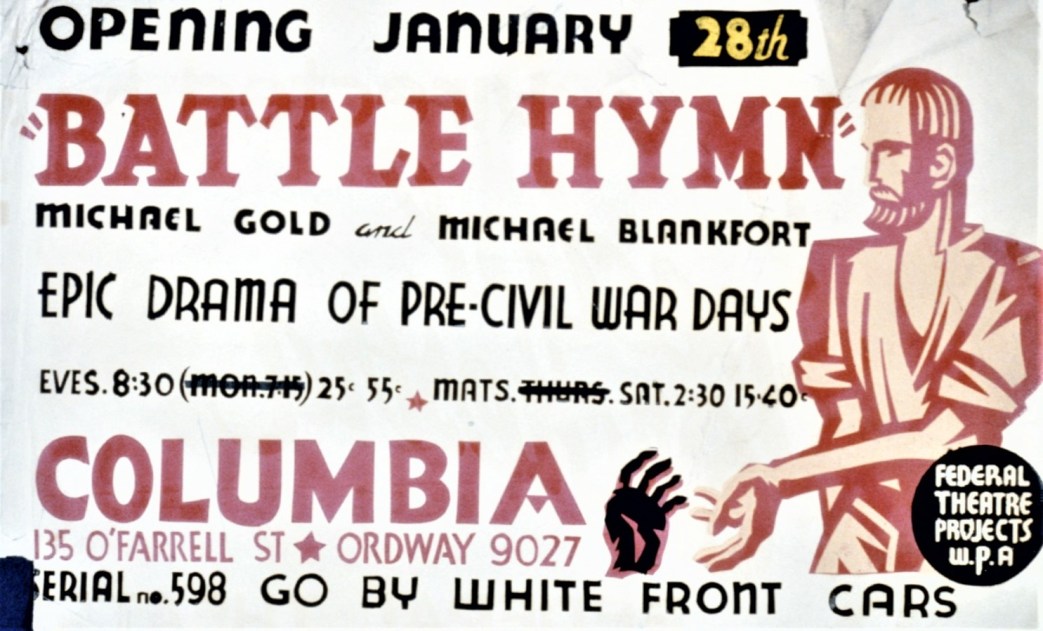

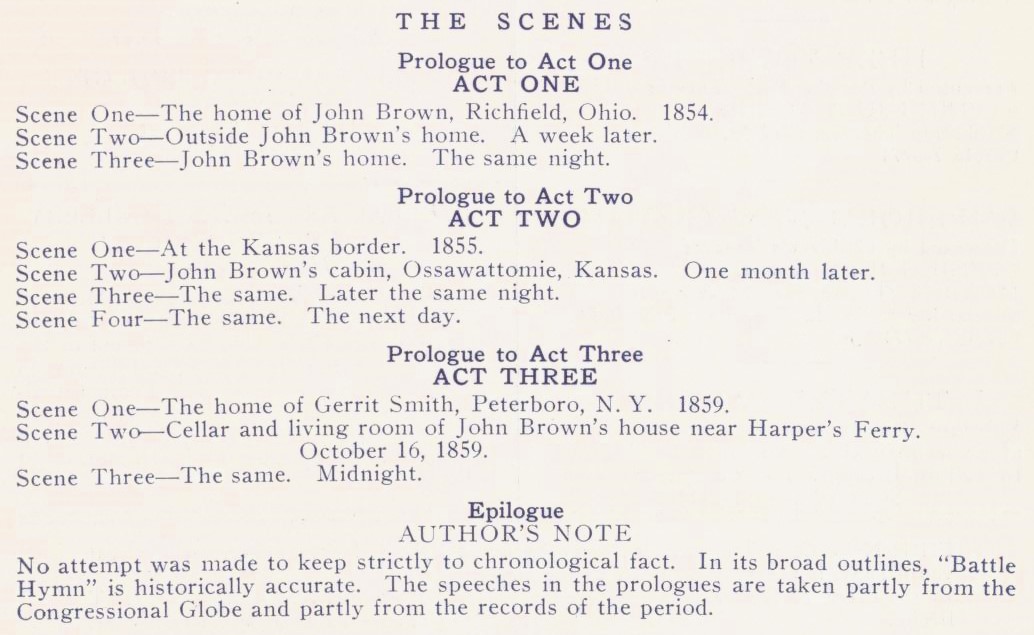

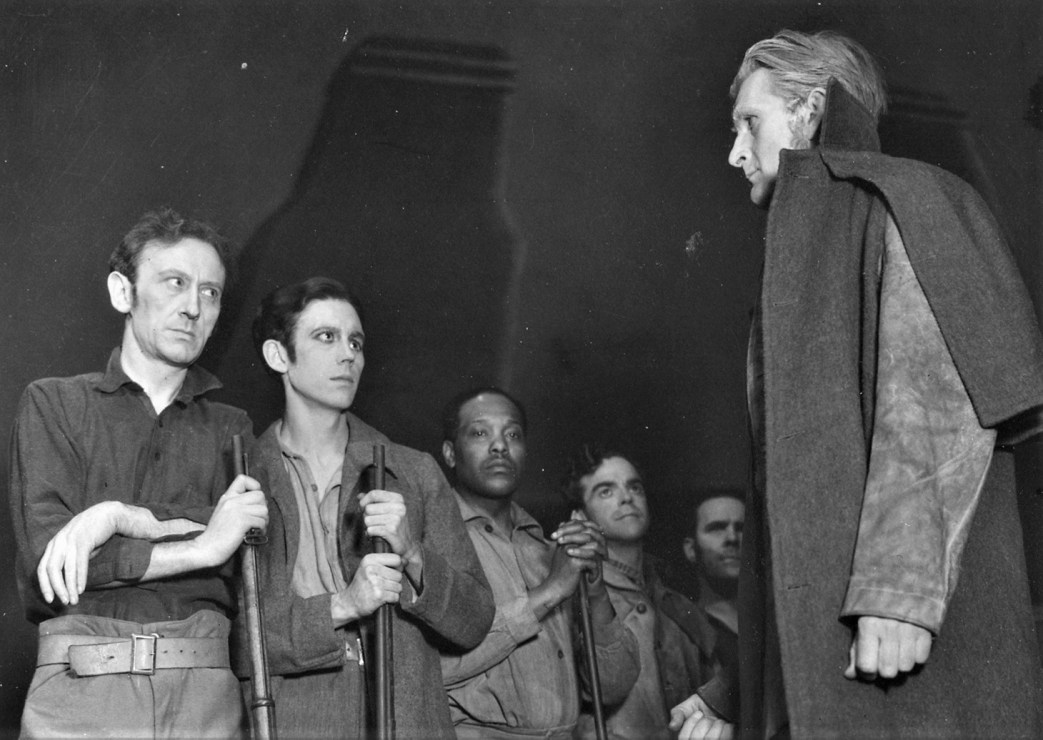

The Crisis talks to Michael Blankfort, co-author of the play ‘Battle Hymn: John Brown of Harper’s Ferry,’ written with Michael Gold and first performed by the Experimental Theater of the WPA Federal Theater Project. The play was based on a series of articles written by Gold for the Daily Worker in 1924 and ran for 72 performances from May to July, 1936 with a multi-racial cast of over sixty.

‘John Brown Re-Created’ by Michael Blankfort and Rus Arnold from The Crisis. Vol. 43 No. 5. Nay, 1936.

The month of May, during which John Brown was born, will see a new play about him called “Battle Hymn” arrive in New York. The author gives here a sketch of the fighter against slavery as depicted in the play.

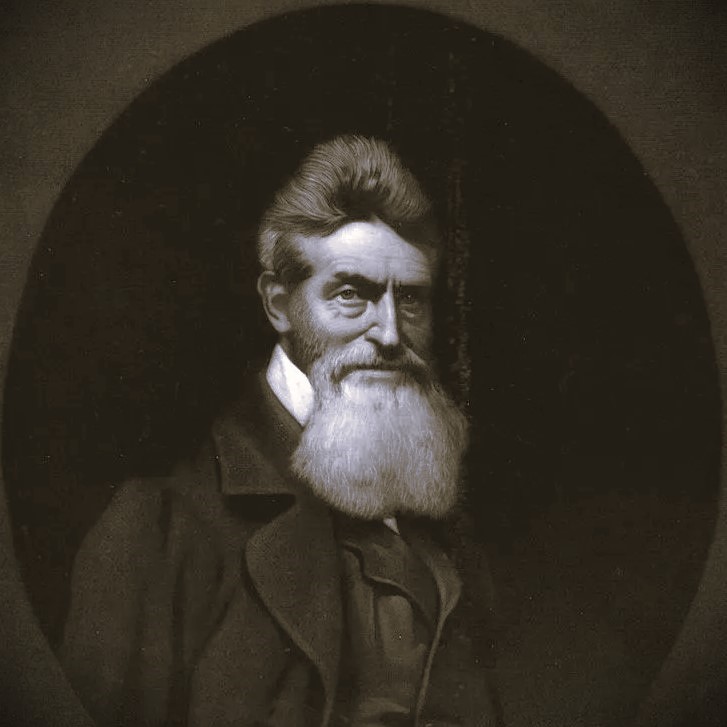

MAY 9th marks the birthday of M John Brown, the great abolitionist. In these times of great conflict and contradictions, the mind runs back inevitably to the pre-Civil War days, and to the outstanding personalities of that time.

Consider John Brown. In him, love for mankind fought with hatred of those who oppressed the weak. He was born a Quaker, and lived a quiet, peaceful half-century—then spent a few years leading a band of fighters, and died on the scaffold for his raid on Harper’s Ferry.

Today we still cannot completely understand John Brown’s character; nor can we do more than merely guess at the cause of his actions. Michael Gold and I found this out when we set out to write a play about him. The play will shortly be produced by the Experimental Theatre, a division of the Federal Theatre, at Daly’s Theatre, 22 West 63rd Street. Yet even after the extensive research involved in writing the play, even after the formulative work of playwriting, we still stand amazed at the contradictions in the man’s soul, the conflicts that went on in his heart.

John Brown spent most of his life as a farmer. Interested in experimental and scientific farming, he was well known for his Devon cattle (the first in New England) and his prize apples. He was equally well known, however, for his poverty. Financially, he was never a success. His large family frequently found itself without food or clothing.

The blood in his veins was of Puritan stock. His ancestors were among the Mayflower passengers. His religion was strict, but produced a nobility of character that was often lacking in the original Puritans. He never broke bread without thanking his Maker; never attempted anything without asking his Lord to send him success and good fortune. Like so many other Puritans and Quakers, he soon found himself allied in feeling with the Abolitionists. The slavery of the Negroes hurt him deeply; he prayed for their liberation. When the underground railroad became well organized, convoying escaped slaves across the border into Canada, John Brown’s farm in North Elba, New York, was a link in the chain. He even tried to persuade some of the fugitives to remain on his farm and work with him.

From Peace to Warfare

Through it all, for twenty years, he remained true to his Quaker love for peace. Even when he went to Kansas to cast his vote, and his sons’ votes, to help make Kansas a free state, he still warned his family that God did not permit bloodshed.

Then he changed. The change was not sudden; it cannot be ascribed to any single incident. All through those two long decades he had been struggling against the feeling that the battle for the emancipation of the Negro demanded more than mere pacific resistance. In Kansas his pacifism lost out; he became an active fighter, and a leader of ruthless men. He approached Garibaldi in daring and desperate zeal. He led forays, slew without mercy, watched unmoved as his brave sons died in battle. Usually he was the victor in the fight. Always he felt he was obeying the will of God.

The culmination of his attack on slavery came in October, 1859, when he gathered a group of Abolitionists and Negroes, ventured into the slave states, and seized the government arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. The United States troops, led by Robert E. Lee, overcame him. Two of his sons were killed; he himself was wounded. The natives wanted to lynch him; the governor interceded and John Brown was legally hanged.

In writing our play, “Battle Hymn,” Michael Gold and I felt that while most of what has been said about John Brown is true, much has been left unsaid. In the light of our modern concepts, and our modern tendency to interpret a man by his background, we must reconsider our old interpretation of the hero of Harper’s Ferry. We might almost label him with some of our modern phrases and titles, if it weren’t for the great contradictions within him, which keep him from fitting into any classification as neatly as a biographer might want to do.

In referring to him, writers usually have considered him insane, fanatic, cold-blooded. They have credited him with no mercy; nor have they noticed any pity or softness of heart. To some extent these writers are justified in so describing him; yet the description must not pass unqualified. Brown might perhaps be likened to a man who must remove a great fish-hook from his brother’s cheek. Even as he rips the hook from the flesh, his heart is filled with pain. Even as John Brown struck his blows for the freedom of the Negro, he grieved at the necessity of shedding blood. That, however, did not stop him from the blood-shed, nor mitigate his heartlessness in the task.

When, at Ossawatomie, Kans., in a battle with the Doyle brothers, Kansas border ruffians, who were trying to keep anti-slavery votes out of the state by force, Brown shot a sixteen-year old boy, he explained his action with the epithetical “Nifs grow up to be lice.”

We must understand, I think, that he was a man of tremendous principle. When he had once decided to do some certain thing, he let nothing stand in his way, and had no mercy for anyone who interfered. Undoubtedly he was a brutal fighter—but his brutality was caused in part of his feeling that bloodshed, much as he detested it, was absolutely inevitable.

Felt Ordained by God

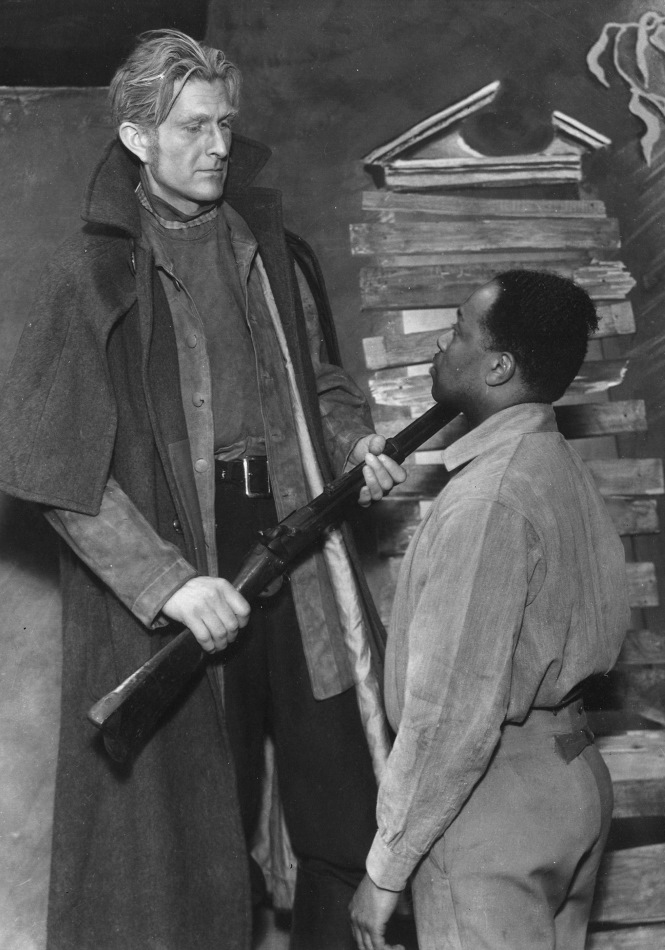

In “Battle Hymn” we show John Brown the fighter-—but we show the pacifist, too. Somehow the play could not be written unless we presented the quiet, peaceful Quaker. Without this view of the man, the other is unfair to his memory. John Brown resorted to violence and direct action only because he was finally forced to realize that prayer was not enough.

When they brought him to the gallows, he wrote this note and handed it to the jailor:

“I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without — much bloodshed it could be done.”

Most authorities agree that he felt ordained by God to do what he did. He is quoted as saying “If God is with me, who then can stand against me?”

Today, however, we see his conception of a God-given mission as a rationalization of the deeds forced on him by the actual material and objective conditions about him. If God was with him, he said, who could stand against him? Yet before raiding Harper’s Ferry he returned North to collect enough men and to arm them properly. When sufficient guns were not available by the date set for the start of the expedition, he delayed until the guns were secured. He went on an errand which, he believed, God had commanded—yet he was not willing to rely on God alone to win the victory for him; he insisted on sufficient men sufficiently armed.

He has been called a violent man. Yet he was opposed to unnecessary violence. He became a terrorist, like Garibaldi and many others who have found it necessary to strike a blow at the existing powers. Yet he dealt out this terror with a gentle hand.

His raid on Harper’s Ferry was an example of what historians today call “an individual act of terror.” The leader planned to overthrow the hold of the slavers on the South. He expected his capture of the Harper’s Ferry arsenal to be the signal for a great uprising of the Negroes in the South-—-He-looked forward to the creation of a great Negro republic south of the Mason-Dixon line. He entered into the venture knowing that it would be a bitter fight, a desperate battle. He was prepared to lay down his life if necessary—but he did not want any of his men to sacrifice themselves for his ideal. Before the battle he told his men that “any who wanted to turn back would be released; he would hold none of them.”

Before the arsenal was captured, he might have burned the city. Other conquerors greater and lesser, ancient and modern, have followed victory with vengeance, have laid waste the conquered territory with fire, blood, or, in modern times, mustard gas. John Brown, too, was a conqueror—but a merciful one. He captured the railroad station and the railroad tracks, but when a train came along he refused to capture it or blow it up. He let it pass; the train went on twenty miles or so and notified the army. As a result the soldiers arrived to capture Brown six hours earlier than they might otherwise have done.

Object of Vilification

His raid on Harper’s Ferry was an act of violence and terrorism, yet he refused to harm his prisoners. In contrast with this is the demand for his lynching after he was captured by Robert E. Lee. When the soldiers arrived and overcame his resistance, a flag of truce was erected. A group of soldiers came in to take custody of him; he respected the flag of truce and submitted. But the slave-holders, violating the truce, fired on his sons.

John Brown was hanged and his body was sent back to North Elba, where it was buried. The man died an object of vilification. Even the minister who performed the burial service over him became an object of defamation and caricature. His wealthiest parishioners resigned from his church. He was branded an “Anarchist,” a “Traitor” and an “Infidel,” just because he had given a decent burial to the body of the man who took up arms against slavery.

Yet we must not forget that it took that man twenty years to make up his mind that arms were needed. John Brown was no young man, entering into the struggle against the evils of existing society out of the passionate hotheadedness of youth. John Brown was a man in his fifties—a quiet, peaceful God-fearing man. We show him as such in “Battle Hymn.” Our problem in the play is the problem of a man advanced in years who is forced by circumstances to change his nature and become a fighter. The drama of the play is the conflict that goes on in the heart of a religious man who finds it necessary to shed blood.

The Crisis A Record of the Darker Races was founded by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1910 as the magazine of the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. By the end of the decade circulation had reached 100,000. The Crisis’s hosted writers such as William Stanley Braithwaite, Charles Chesnutt, Countee Cullen, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Angelina W. Grimke, Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Jean Toomer, and Walter White.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_crisis_1936-05_43_5/sim_crisis_1936-05_43_5.pdf