The second chapter in Vern Smith’s marvelous serial on the sea.

‘Sea Power II–Evolution of the Ship’ by Vern Smith from the Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 2 No. 6. October, 1924.

It is supposed that the keels of ships evolved from the center plank or log in a raft (which was sometimes bigger than the others), that the side planks of ships came from the fence around the raft platform, or from planks or shields used as bulwarks on a big dugout canoe, and that the ship’s ribs have evolved from bars used to strengthen the sides of “sewed ships,” such as the Madras surf boat. This is all pure speculation, and sounds a little fanciful.

But we know the Egyptian ship fairly well from the pictures in the tombs, from the descriptions of Herodotus and other Greek writers. It carried a square sail with yards, and tackle for raising them. The mast was in two pieces, stepped apart at the bottom, lashed together in the middle, and separated a little at the top, again, to hold the yard between them. There was an upper, spar deck. The boat carried 20 to 26 oars on a side, in one bank, and had a raised bow and stern, and a ram (above water) for attack on other boats. There were four or five paddles joined together for steering, and they were worked by a tiller. We have pictures of boats carrying cattle.

These ships made trips out of the river Nile into the Mediterranean. They sailed as far as Crete, on which Egypt had a colony.

The Phoenicians made the ship larger, primarily for Mediterranean rather than river usage. As early as 900 B.C. they had decked ships, and especially they invented the bireme and trireme, the galleys with the rowers seated ’tween decks, and with one row of oars above another. This was the type of vessel, especially used for war, for at least two thousand years. The scheme by which the rowers managed to sit one above another and still have leverage for their oars, was a very ingenious one, not discovered again until 1834 when the records and plans of an Athenian shipyard were unearthed. The arranging of oars in “banks was done by seating each higher man about two feet astern of the man below, and two feet higher, on nine inch seats. Each man could put his feet on a foot rest on the seat in front of him. One hand had to be held at a peculiar angle, awkward at first, in order to avoid bumping the neighbor with the oar. Rowers were literally “packed like sardines in a box,” and the maximum power was given to the ship—or so they thought at that time.

Standardized Product

The Athenians (the greatest of the Greek naval powers, reaching their height in the fifth century B.C.) put out from their ship yards a standardized galley. (See how capitalistic practices such as standardization naturally apply to shipping.) The length of this ship (trireme) was 128 feet exclusive of a ten foot ram. The breadth at the water line was fourteen feet, the extreme breadth was eighteen feet, exclusive of a two foot gangplank which ran lengthwise ‘of the ship, all around, over the oars, and was used for fighting. This trireme carried a regular crew of 174 rowers, ten marines, and twenty seamen. She couldn’t carry much cargo.

The ships of the Romans and of the Carthaginians who succeeded the Athenian Greeks as naval powers were about the same as the Greek vessels, except for a tendency (afterwards abandoned) to use ships of four and five banks of oars.

After the destruction of Carthage by Rome, the latter’s need for ocean commerce decreased, and the state became a great landlord and serf empire, drifting slowly toward feudalism. Shipping declined, and boats were made smaller instead of larger.

In fact, they started all over again, after the downfall of Rome, and the Mediterranean people made a discovery. They found that if they used one bank of oars instead of several, and put four or five men to each oar, they economized space even more than the trireme did, and got more power per oar. All medieval galleys are distinguished from the ancient galleys by this, that the ancients went on the theory of ‘‘one man, one oar,” and the later shipmen introduced social or co-operative labor, even into the rowing of a single oar.

The Civilizing Compass

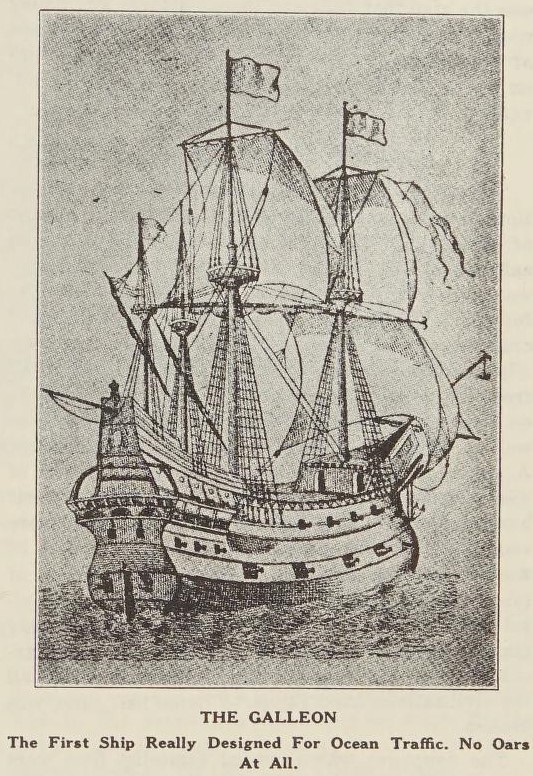

Then the great discovery was made—or rather, there was a discovery combined with an evolution and development of two old discoveries. The compass was introduced into general use. We call this a discovery, because, though it is undoubtedly true that the Chinese had a compass long before it appeared in the West, there is no evidence that the western compass came from the East, and in any event, its widespread use, very suddenly, seems to be characteristic of a real discovery. It is hard to overestimate the importance to the history of mankind of this single event, and its immediate quickening effect on all other inventions was almost miraculous. The compass appeared about 1100, and in 1115 the first three-masted sailing ship was launched, at Venice, the first of a type which soon developed into the historic galleass and into the ‘great round ship,” and the galleon—all sail ship, not galleys, though the galleass has sweeps for occasional use.

The connection between this improvement of ships and the compass is easy to see. With the compass, a course can be laid out and steered out of sight of land. Navigators in the Mediterranean could steer by stars, before this, though they usually did not, for fear of clouds and storms. But in the northern waters of the Atlantic, to which Venetian and Genoan ships after this regularly sailed, and in which native shipping increased the storms and fogs were a constant risk, and little commerce was possible before the compass. Such Viking traffic in galleys as had been there was not merchant traffic; at the best it was colonization; at the usual worst it was murder and robbery. Ocean trade was made possible by the compass, direct voyaging was made possible by it, with a great shortening of the trade routes. The art of navigation immediately developed, the sextant came into use, and the building of larger ships, using sails as their prime source of power, big enough to be relatively safe from pirate galleys, was the step that followed immediately. The galley was still used for war until the general employment of cannon about 1450 gave the big sailing ship with its heavy broadside of 24 and 42 pounders an advantage over the necessarily smaller row boat.

Some Factory System

The big sailing vessel stimulated ocean exploration; the discovery of the route around Africa, and of the Americas, hurried along a change in human affairs that had already got well under way. Money was to be made by merchant adventuring; there was for the first time a world market; all the arts and crafts were stimulated; manufacture developed rapidly in the towns; new materials were brought back from the near East by crusaders (ferried over there on Venetian ships) ; and this manufactured stuff, as well as the spices of the Orient, was carried by sea. A capitalist class developed, and their source of wealth was the sea, first of all. They invested their hordes of capital in factories, even before machinery was invented. The assembling of large numbers of workers in the same shop developed division of labor, and the machine came to do the now mechanical processes of weaving, spinning, etc. The world turned capitalist, and one invention followed another. The old deadly routine through which all the civilizations from Egypt to Rome had gone, was broken.

The countries which turned capitalist first were those which were best adapted for shipping. The Italian cities were too far out of the ocean lanes to compete with the Portuguese.

The Portuguese were not able to defend themselves on the land side from Spain. Spain itself, being a big agricultural country, and nearly continental at that, failed to carry on her sea power very long. One reason was that her colonies were primarily sources of precious metals, and not of useful products. The wealth that comes from gold and silver mines is a very unstable foundation for national greatness. The mines work out.

The German cities came almost to winning the great prize The group of several hundred cities called the “Hanseatic League” was developing capitalism in Germany over night. But the Hanseatic League had as its chief source of revenue the trade in herring, which they caught in the North and Baltic seas. For some reason, the herring, about’1400, all left the waters easily reached by the ships of the Hansa and went to English and Dutch waters. Amsterdam was “founded on the herring.”

Some “Primitive Accumulation”

Holland turned bourgeois pretty fast. The “Beggars of the Sea,” Dutch ship owners, smuggling, engaging in piracy, landing and plundering at times on hostile coasts, trading East Indian spices, silks, perfumes, to Spain at the very time their country was fighting a war of life and death with the Spanish government, taking revenge for the hanging of Dutch protestants by cheating Spanish Catholics, laid the foundation of the sea power of Holland. The country was a natural harbor, with water communication with the interior.

But England, even better situated, based her commercial ascendency on the textile trade (for which the British isles could supply both flax and wool) and in which the use of machinery for manufacture was introduced before it came to any other industry. Capitalism by 1680 had so firm a hold in Western Europe that national ascendency depended rather on manufacturing advantages than on commercial. In the end, England won supreme control of the sea, commercially, and militarily. Her control was riveted tighter by the change to steam power (invented in America in the early 19th. century—the Cleremont sailed in 1807) and by the use of steel ships (common by 1870). England’s one disadvantage had been the necessity of importing “naval stores.” Now she made whatever was needed in her iron foundries.

It may be noted here that as the first lunge of capitalism for power, in the later middle ages was accompanied by, and probably caused by, the change from the oar and sail to the sail alone as the chief motive power of ships, so the change from small scale bourgeois production to large scale, monopolistic production was accompanied by, and to some considerable extent caused by, the change in ocean going ships from the sail to steam as the chief motive power.

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/industrial-pioneer_1924-10_2_6/industrial-pioneer_1924-10_2_6.pdf