A tour de force of a Marxist literary critique from the formidable Charmion von Weigand. In this extensive essay on the towering figure of U.S. theater in the twentieth century, von Weigand traces Eugene O’Neill’s artistic development and his relationship to larger American culture. Written at the the end of his ‘middle period,’ just before he won the Nobel Prize in 1936, particularly revealing is von Weigand’s analysis of O’Neill’s racial and class world-view through his characters and character. Will be of great interest to all O’Neill scholars, as well as students of U.S. theater, and of Marxist art criticism. Major.

‘The Quest of Eugene O’Neill’ by Charmion von Weigand from New Theatre. Vol. 2 No. 9. September, 1935.

From the Moon-Drenched Caribbees to the Foot of the Cross

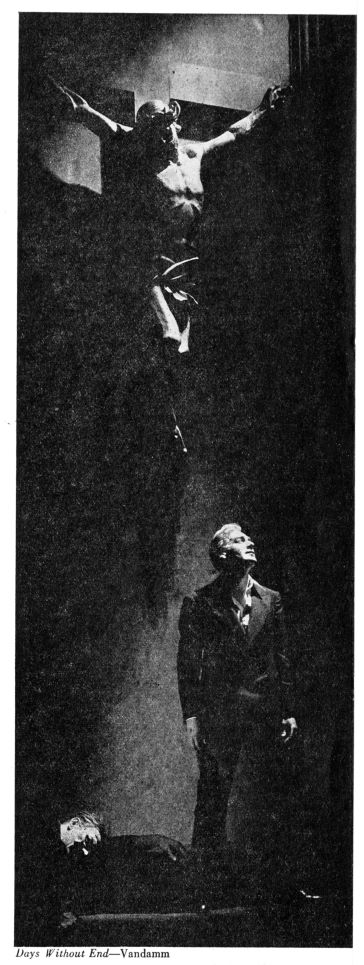

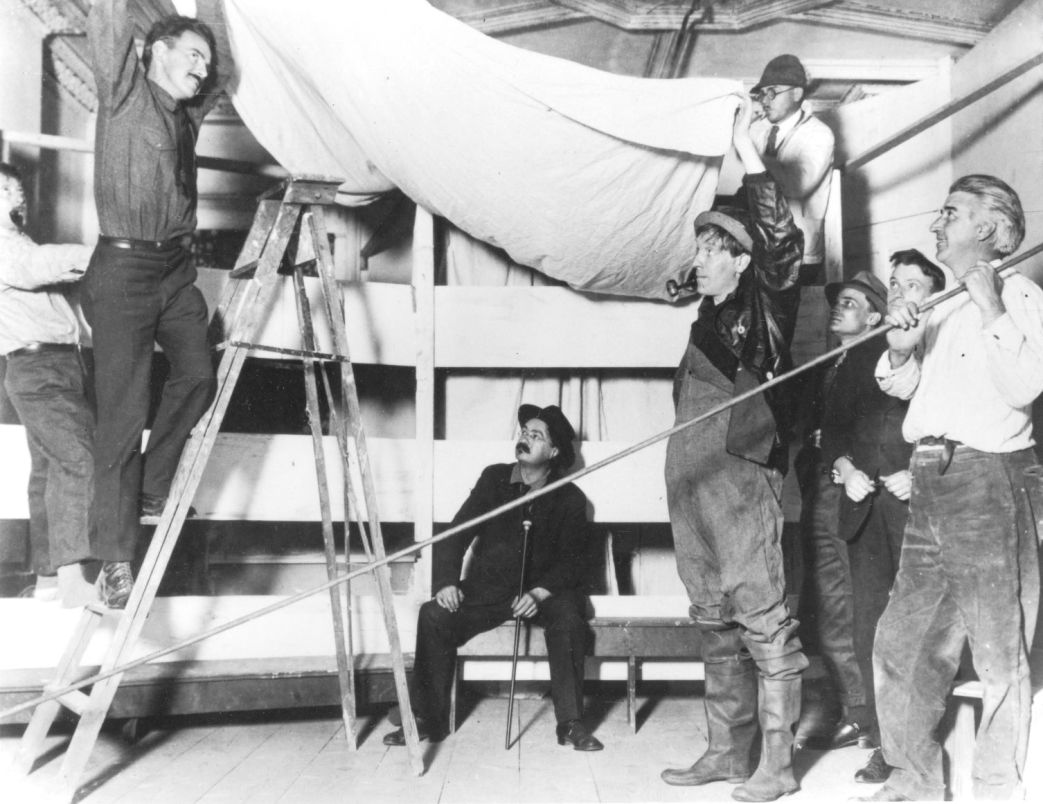

When The Hairy Ape was produced by the Provincetown Players in the spring of 1922, a number of radical literati jumped to the conclusion that Eugene O’Neill had writ ten a revolutionary, even a proletarian play. Nothing could have been further from the truth. Because of this initial error, radicals in 1934 were astonished and disappointed to see Days Without End, a play in which O’Neill sought refuge in the bosom of the Catholic Church. They felt as if he had betrayed not only them but himself.

Yet few playwrights of modern times have been more consistent. The journey from the moon-drenched Caribbees to the foot of the cross has been a steady and necessary progression. O’Neill himself has made no bones about the meaning of The Hairy Ape, although he never grasped the full implications of his own play. In 1924, he wrote:

“The Hairy Ape was propaganda in the sense that it was a symbol of man, who has lost his old harmony with nature, the harmony which he used to have as an animal and has Drama and Will not yet acquired in a spiritual way. Thus, not being able to find it on earth nor in heaven, he’s in the middle, trying to make peace, taking the ‘woist punches from bot’ of ’em.’ This idea was expressed in Yank’s speech. The public saw just the stoker, not the symbol, and the symbol makes the play either important or just another play. Yank can’t go forward, so he tries to go back. This is what his shaking hands with the gorilla meant. But he can’t go back to ‘belonging’ either. The gorilla kills him. The subject here is the same ancient one that always was and always will be the subject for drama, and that is man and his struggle with his own fate. The struggle used to be with the Gods, but is now with himself, his own past, his attempt to belong.”

Here we have from the author himself the key not only to The Hairy Ape but to his entire works. Hailed as a daring innovator in the drama, O’Neill was never a revolutionary writer neither in content nor in technique. The rebellion which he dramatised was rooted in old moral presuppositions. It is true that in his early plays there appear proletarians: sailors, stokers, farmers, Negroes, poor whites, white collar intellectuals. But these characters seen through the eyes of their author who never penetrates beneath the surface to their real psychology embody merely the more lurid, romantic, exterior aspects of such people. When O’Neill develops a character internally, the character is always a middle class intellectual seeking to escape into another class.

This type of escape resembles somewhat the annual excursion of the summer tourist to Europe; he deserts his native milieu for a foreign and exotic one; here, unhampered by home conventions, he temporarily enjoys a spurious freedom. But it would never occur to this tourist to take out citizenship papers and to settle down in a foreign country. It never occurs to O’Neill to desert his own class and to align himself with the working class.

In his first plays, O’Neill employed the sea or the farm as a backdrop for the romantic dissatisfaction with life. He portrayed sympathetically a series of poor, morbid, unhappy characters. In the Broadway theatre with its indoor drawing room setting and its conventional bourgeois characters this was a startling novelty. But never once did O’Neill explore indicate that their psychic disturbances had the depths of his characters; never did he roots in social ills. The misery of the poor as of the rich was always ascribed to a malignant fate working havoc with man’s life.

From the beginning, O’Neill has been the dramatist of the petty bourgeois intelligentsia, lost between the heaven of the upper classes and the earth of the proletariat. Not yet fifty, he has written a score of full length plays and half as many short ones. He is at an age when his most mature creative work might be expected to be ahead; yet his plays may already be viewed in retrospect, since like his illustrious literary forbears, Chateaubriand and Huysmans, he has collapsed in the arms of the church. The dramatist who will emerge after such a religious conversion can never be quite the same as he who wrote The Great God Brown and Desire Under the Elms.

At bottom O’Neill’s ideas are the ideas popularised by the French Revolution. This is why his development so closely parallels the development of the famous romantics of the latter part of the 19th century.

The primary problem of western drama has always been the problem of the will in action. In a period of cultural upsurge, the social will of the individual is healthy and functions normally toward a given goal, which may be reached by active striving. In a decadent period, on the other hand, when society is sick from ill-balance, the social will of the individual becomes weak, hesitant, atrophied, incapable of consciously striving toward a goal and the goal itself becomes obliterated, obscure, or split into numerous goals. Of course a healthy society may contain individuals with sick wills. In the robust period portrayed by Shakespeare, we find a Hamlet, but it is interesting that in spite of Hamlet’s conflict and indecision, he achieves action in the end. Whereas in an ailing society, the will of a healthy individual may assume all the characteristics of the illness of the society. Both Hedda Gabler and Rebecca West were women of strong will without any outlet for their thwarted energy; both, in the society in which they lived, were doomed. Long ago 19th century dramatists in Europe had begun to feel the laming of the will which came with a slowing of the creative processes in bourgeois society and their plays reflected the conflicts which grow out of the dislocation of the will and the deed. The climax comes in the drama of Chekov where we are treated to a picture of a will-less intelligentsia throttled by censorship, deprived of political life, and sentenced to a goal-less, aimless existence without even the hope or the desire for action. The favorite characters of O’Neill all exhibit a serious conflict of the will.

In order to grasp more fully the meaning of O’Neill’s plays, it is necessary to examine the social roots of his development. The post war period in the United States witnessed a revolt of the secure and increasingly prosperous middle class intelligentsia from the conformity, ugliness, and standardization of Main Street, with its Babbitt concern for church socials, sports, movies, gin and clandestine sex. In literature there were many spokes- men of this revolt, which spread like prairie fire throughout the country. An integral part of the new mood was the little theatre movement. The Carol Kennicotts of cultural adventure, who could not escape to the South Seas, Spain, or Greece, set up temples of art in the family barns, where they burned their orange candles at both ends in homemade Bohemias patterned after Greenwich Village and Provincetown. They demanded plays which voiced their inner discontent and which could be produced with two yards of theatrical gauze and a set of kitchen chairs and table. At this time, O’Neill, who had spent a year in Professor Baker’s famous playwrighting class Harvard 47, was turning out one act plays simple enough for amateurs, yet embodying what seemed at the period a stark, relentless realism with a poetry of discontent profoundly nostalgic.

A Hostile Cosmos

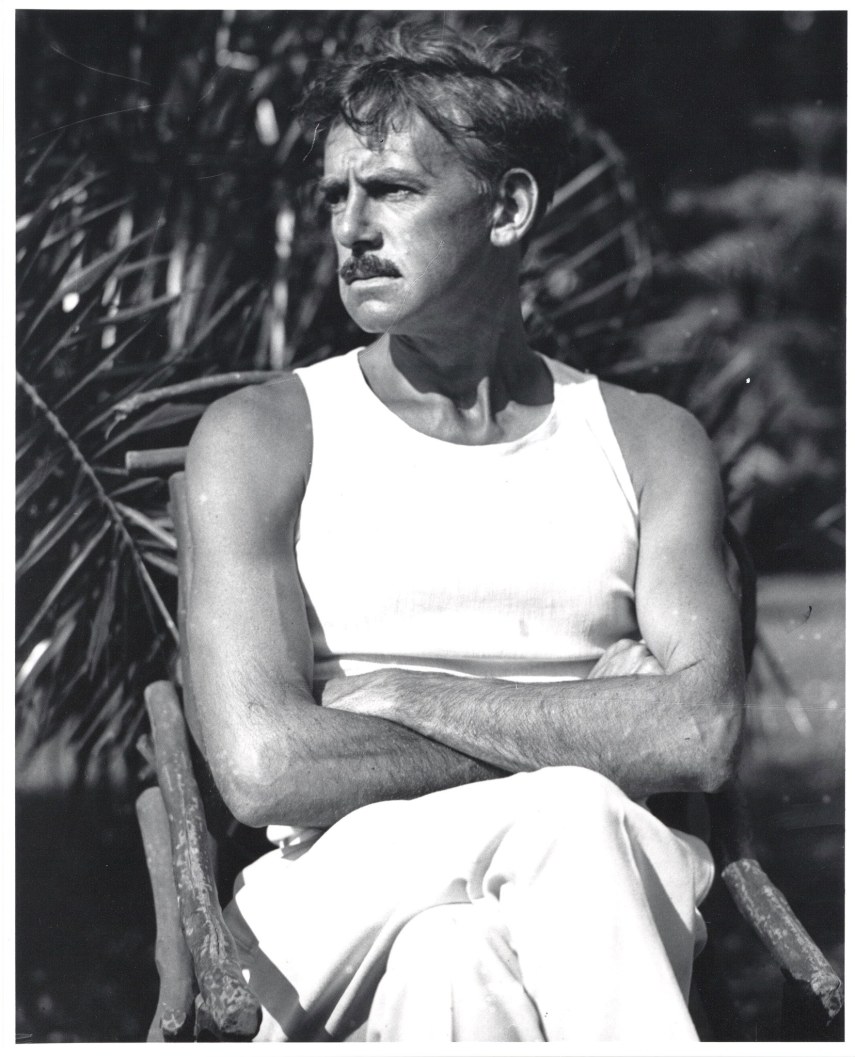

O’Neill was at first above all a spokesman against Main Street–the drab conventional life of the ‘average” American. His revolt took the form of flight. Sailing on a Norwegian ship for Buenos Aires, he experienced the life of a sailor at first hand. In all, he made four sea voyages and became an able seaman. Contact with crude reality, which remained in some respects his chief experience with the external world, left an indelible impression on his sensitive nature. The result was a series of one act plays later produced under the name of SS Glencairn. All deal with the sea; the gorgeous moonlight nights of the Caribbean, its tropic islands, its sinuous brown women, are contrasted with the hard-drinking, hard-working, lives of the sailors. These plays are in some respects the best things O’Neill ever wrote; their mixture of poetry and bad language was refreshing in the stale theatre of the period. Today their realism seems tinctured with romantic tradition and their bad language has become a convention in literature, a convention developed and handled with more mastery by Hemingway and other younger writers.

Seemingly formless both in technique and content, these early one act plays contain the gist of O’Neill’s major concern the struggle of his own ego with the universe. He constructs a primitive, hostile cosmos pervaded by a blind fate hanging like the sword of Damocles over man’s life-a fate in no wise effected by social forces or relationships. All his work mirrors a baffled quest for the long lost innocence of happy childhood: his plays are never ends in themselves but stepping stones toward his unreal goal. Fruitlessly the quest has led him away from reality to each of the traditional escapes of the romantics.

II.

O’Neill’s first really organized effort at drama was the long play Beyond the Horizon. Here he counterposed the romantic symbol of the earth as the mother of man, and the sea, as the symbol of freedom, dramatizing the conflict between the farm and the sea, as if these two elements were the chief characters of the drama. The actual characters and the setting are naturalistic, yet there is a tremendous yearning to escape from the material and concrete in life. Robert and Andrew Mayo are brothers already indicating the dual nature of O’Neill later fully developed in The Great God Brown and Days Without End. The former longs to go to sea to seek his dreams “beyond the horizon” and the latter longs to till the soil and create something from it. But fate intervenes in the person of Ruth, who promises love to Robert. The roles are reversed. Andrew, the practical man, goes to sea; Robert the dreamer remains to run the farm. Both suffer disillusionment and failure, for inherently both are the romantics, who cannot face reality. The plot of the play is developed like a novel, and this technique is used to spread the story over a long period of time. In this way the author evades bringing the characters together at a crisis, which would involve choice and a directive will power. This evasion is not due to O’Neill’s ignorance of the rules of the well-made play, for he was brought up in the Broadway theatre, and from the beginning understood its craft; it must therefore be attributed to a psychological aversion to a crucial choice! Time solves the problems of the characters in Beyond the Horizon; through the long years they remain passive instruments of an environmental fate. They scarcely ever act and when they do, they act to their own detriment; as in Act I when Robert, about to fulfill his desire of going to sea, changes his mind at the last moment, and sends his brother instead. In fact the whole plot is evolved from this false choice, which proves an evil fate to everyone. Perhaps Robert was a victim of what the Freudians call “scheitern am Erfolg,” that catastrophe on the threshold of success, which comes from the fear of it. He did not dare to face the consequences of realizing his heart’s desire, the voyage to sea. Hence his action in giving up the sea is not an act of will, but an escape from the consequences which an act of will involves. His brother Andrew, while supposedly practical is haunted by the same fate—a desire to escape from his heart’s desire. Thwarted in love, he leaves the farm, his life work, and goes to sea, gaining prosperity and betraying his love of the soil by speculating in wheat.

O’Neill’s repudiation of action and his emphasis on natural environment rather than on social background, has led him to depend on mood to carry his drama. Already in this first play, he is a master of mood. He is able to create atmosphere an atmosphere that overhangs and sweeps through his later plays, the primitive sounds and colors of the jungle in the Emperor Jones, the macabre, sensual-puritan conflict in Desire Under the Elms, the morbid decaying lilacs of Mourning Becomes Electra. In this sense, his plays often achieve lyric poetry.

Compare O’Neill’s last play, Days Without End with his first long effort, Beyond the Horizon. The dialogue shows no inner development, no essential quality, that makes it inevitable, nor does it lend itself to quotation when torn from the context. When one remembers how the dialogue of Shakespeare has enriched the English language or even how Bernard Shaw’s quips have enlivened the conversation of the present day intelligentsia, one has an inkling of what creative dialogue may accomplish.

In Beyond the Horizon O’Neill’s dialogue is cast in naturalistic form, but the speech misses the tang of spoken language. Only in ecstasy, madness or drunkenness do his characters speak out of themselves as if from an imperative urge. Hence in later plays where he shifts from naturalism to super-naturalism, the dialogue has a more sensitive quality. Like his master, Strindberg, O’Neill is most at home when he is dealing with neurotic, over-strained individuals. The theme of madness is ever recurrent in his plays. It occurs already in one act plays When the Cross is Made, and Ile, and it is developed further in All God’s Chillun Got Wings, Strange Interlude, Dynamo, and Mourning Becomes Electra.

It is O’Neill himself who has revealed that the sea which is the romantic symbol of man’s freedom in Beyond the Horizon is a snare and delusion. In the one-acter, Ile, the wife of a whaling captain has dreamed of the free, noble life on shipboard, but taken on a voyage, she discovers that it is merely another form of captivity, enlivened by brutality, meanness, and monotony. When her husband insists on heading the ship northward away from port, and she is doomed to remain on board, she goes mad. Insanity may be an escape for some individuals but it solves no problems for the world as a whole. Hence O’Neill is compelled to seek some other romantic solution for human happiness.

Yet having portrayed life on the farm as drudgery, poverty, and monotony and life at sea as the same dull routine, O’Neill is still incapable of making the final judgment; that it is capitalist society which condemns the worker to slavery regardless of environment.

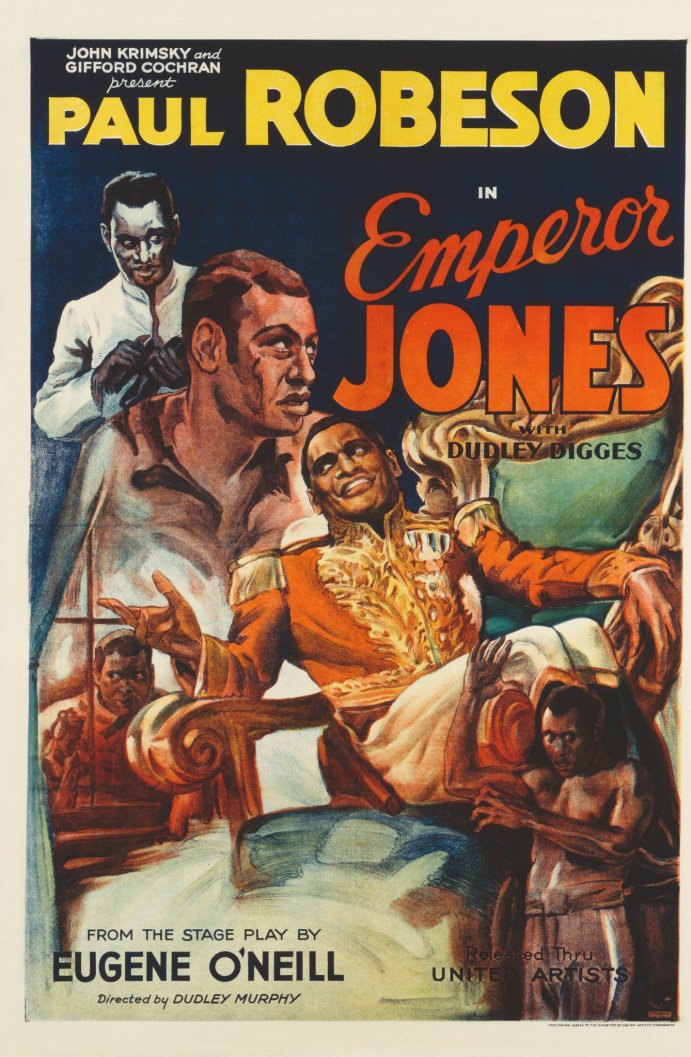

He continues the search for happiness in The Emperor Jones. Because of its use of expressionist technique and its choice of a Negro for hero this play was the sensation of its time. Actually its basic idea is as old as Rousseau. We have the return to nature in the person of the simple, happy savage unhampered by the cares of civilization. The hero, an ex-pullman porter, a civilized American Negro, with all the vices of the white man, has made himself king of a tropic island. Threatened by the natives, whom he has ruthlessly exploited, he plans escape back to civilization, where he may enjoy his stolen gains; but caught in the jungle, his progress becomes a backward journey into the racial memories of primitive existence and only the fatal legendary silver bullet stops his flight.

The Meaning of Expressionism

The Emperor Jones departed from the conventional theatre of the time in two ways. It broke with the technique of the well-made play, with its solid three or four acts building to a climax. Instead it presented the scene succession of expressionist drama most successfully. The method was in keeping with Jones’ flight through the forest and the fantasies he meets. Actually the play is a monologue with pantomime, for the other characters are either shadows of Jones’ dream or else are introduced for local color and atmosphere. Jones is the sole protagonist.

O’Neill has been accused of borrowing this new stage technique from the Germans but he has denied the influence. There is no reason to doubt that he came to the method independently of the post-war German dramatists. But both the Germans and O’Neill have been profoundly influenced by Strindberg, who is actually the father of modern expressionism. It was Strindberg even more than Ibsen who reflected the breaking up of the organic relationships of bourgeois society and mirrored the resulting soul sickness of the intelligentsia. In Strindberg unconscious fantasy takes possession of the stage and drives out the every day world. This was already apparent in the later Ibsen of When We Dead Awaken. Expressionism represents not a beginning but an end. It celebrates the destruction of old forms in art and society and their dissolution into separate units. In expressionist art, the boundaries of form are loosened. Drama approaches painting and music, painting simulates music, and music painting. Likewise the boundary between the natural and the super-natural is obliterated. The dream assumes the vividness of reality and reality takes on the color of the dream life. Literature disintegrates into words and the words themselves lose meaning and become merely sound. Form in painting is dissolved into juxtaposed spectral colors. The disintegration of a social class sends its destructive vibrations into the most distant ivory towers of the intelligentsia and the arts prophetically assume the sunset colors of the end. Expressionism in painting, poetry, drama and music was perfected by the post-war Germans; it was a technique adapted to the petty bourgeois intelligentsia in pursuit of its own soul across the chaos of German society before that same intelligentsia had split into Fascist and Communist partisans. Eugene O’Neill, also a member of the petty bourgeois intelligentsia, unconsciously selected a method appropriate to a period of crisis in the halycon days of the twenties in America and thus prophesized all unawares the coming economic and social crisis in a period of apparent prosperity and stability.

III.

At the time of its first production, many people believed that in The Emperor Jones O’Neill had intended to champion the cause of the Negro. As a matter of fact, he was not at all interested in the Negro and his actual problems in the United States. Nor did he ever make any pretense of championing the Negro as a member of an oppressed race caught in the toils of imperialist exploitation. He used the Negro as a symbol of the lost paradise of the primitive world, a world as much a part of the white race as of the black. His interest in the Negro as a hero derived merely from his quest for happiness, and an unsuccessful attempt to solve it by a return to primitive nature. It is O’Neill himself who is hidden behind the black mask of Jones.

The story of the play may have been derived from some legend of the strange emperor Christophe in Haiti but O’Neill had no interest in the actual island of Haiti. He found there merely a jungle backdrop. Nor had he any interest in the history of the struggle of the Negroes of the islands. In a recent Soviet novel, Black Consul, the struggle of the islands for independence in the period of the French revolution has been depicted. Against its social background, we see the full stature of that heroic Negro leader, Toussaint L’Ouverture. What a contrast to Emperor Brutus Jones, who is given all the vices and none of the virtues of the whites. Contrasted with him is Smithers, the white cockney, a thief and degenerate, who nevertheless feels himself the superior of Jones. O’Neill implies that white supremacy will always exist, that the human being is not capable of progress, that life does not change. The ex-pullman porter, who has acquired civilization, put back in his native environment, retrogresses to savagery and his aboriginal fears. With O’Neill, the Negro is always represented as a degenerate savage or ineffectual neurotic.

The Negro As Symbol

In the one act play The Dreamy Kid, we see a young Negro gangster who has committed murder but who has a sentimental and superstitious fear of leaving his dying grand- mother and this fear leads to his capture. In that play of miscegenation, All God’s Chillun Got Wings, the hero is a studious and sensitive Negro but the peevish and malevolent destiny which governs O’Neill’s cosmos allows no way out for him, anymore than for the Emperor Jones or the Dreamy Kid. This story of a mixed marriage raised a storm of protest at the time of its first production. But on examination, it is apparent that O’Neill only superficially departed from the prejudices of his class as regards the Negro. If he had intended to poise the problem whether there could be a happy marriage between a Negro and a white, he would have chosen two equals to mate; the conflict would thus have been all the more intensely dramatic. Instead O’Neill leaned over backward in his attempt at fairness and in this action reveals his prejudice. For the story sets forth how Jim Harris and Ella Downey are doomed to fail from the start, but the failure of their marriage is not due to a difference of races but to a difference of culture. Brought up together on the East Side pavements, Jim, the Negro boy, and Ella, the Irish girl were childhood sweethearts. But when they meet years later and marry, life has dealt very differently with them. Ella has been a prostitute and has been deserted by her lover, the gangster Mickey, after she has born their illegitimate child. Jim, on the other hand, is a sensitive, educated man, well off from the money his father earned trucking. Ella accepts Jim because he can give her security but grows to hate him because she feels inferior to him both in culture and character. This arouses her race antagonism and she tries to keep Jim down in order to keep her self respect. She centers her neurotic conflict around making him fail at his law exams. She can maintain her white ‘superiority’ only by making clear to him that he is too stupid to pass the white man’s test.

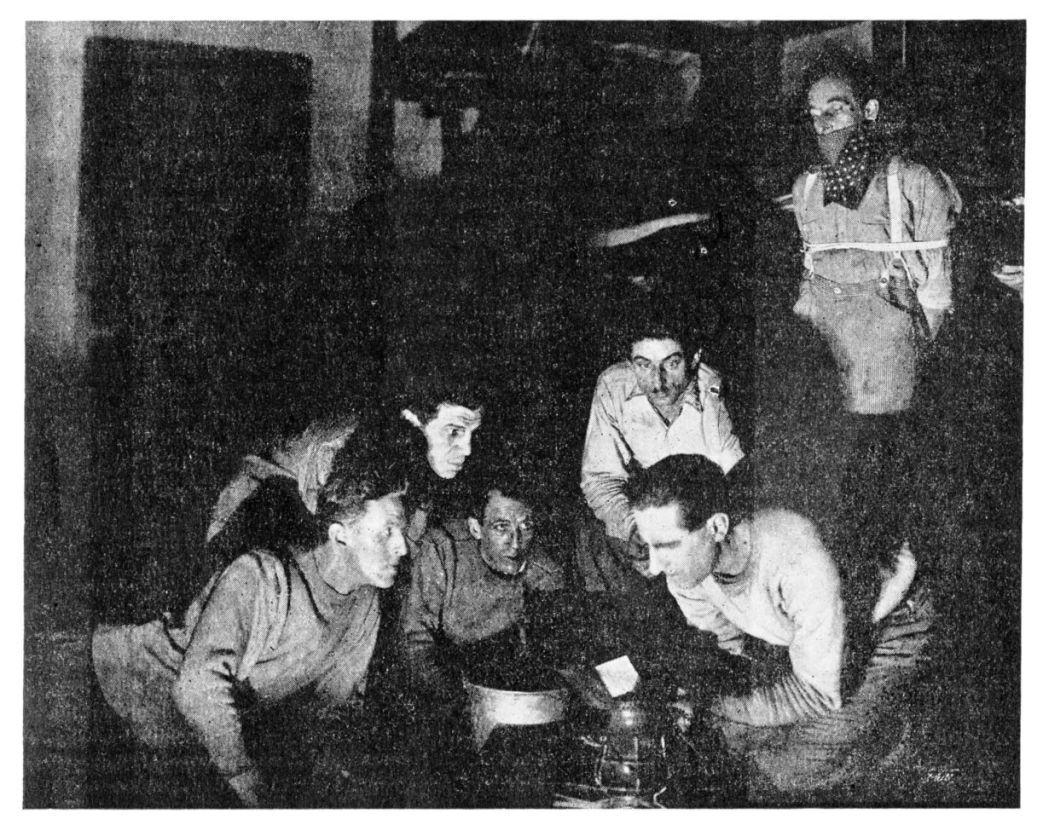

That the Negro is used in the O’Neill plays as a symbol of the primitive nature of man becomes clearer in The Hairy Ape. Here the hero is a white worker with a hairy chest who discovers that he has no place in the world as it is made today. Again O’Neill employs an expressionist method, a sequence of swiftly moving scenes, in place of the solid act, which organically unfolds and develops an idea. Theatrically this is one of his most successful plays. The action moves with speed and inevitability, but it is a retrogressive and disintegrating action as in The Emperor Jones.

Yank, a stoker on a transatlantic liner, symbolizing the machine age, is insulted by a passenger, a girl of the upper classes. He discovers that he does not ‘belong.’ He sets out to get revenge on the girl’s rich family, to find his place in the scheme of things. Violent and anarchic in his rebellion against society, Yank is repudiated by all–even by the I.W.W. He becomes an outcast everywhere. After a series of futile attempts to find a place, Yank lands at the zoo. The gorilla, symbol of the primitive past of man, repudiates him too. Yank is strangled to death in the gorilla’s hairy arms.

On the surface The Hairy Ape may appear to be a proletarian play. It deals with a worker proletarian, who is exploited and cheated. But actually the hairy chest of Yank is another mask disguising the petty bourgeois intellectual. The play voices the terror of that intelligentsia in a disintegrating bourgeois society; the proletariat is represented as brute force without intelligence and without culture; the upper classes are represented as shallow, cruel and cold. Unable to make a choice between the two classes, the petty bourgeois intellectual regresses to the old primitive world, but the path backward from organized bourgeois society to nature in the raw leads not to happiness but to death. The simple happy savage of Rousseau is an Utopian dream in our modern industrialized world, and the intellectual who seeks that ideal of the past meets only with disaster.

O’Neill sends Jim and Ella to Europe, as if to demonstrate that even in France where race prejudice is of a milder form, such a mating cannot be happy. But what are the facts? Jim’s greatest weakness is a social one, for while he has educated himself, he has remained emotionally and sentimentally attached to the values which he acquired in the tough neighborhood on the East Side. Jim’s education and money should have freed him from his old milieu and enabled him to find a place among the intelligentsia, but he himself believed that the Negro is actually inferior to the white man. He accepts Ella’s prejudiced judgment as the truth. He allows her to keep him from social life in Flight to the Past France, where they might have been accepted. The fact is that Ella is less ashamed of her Negro husband, than afraid that before people who do not accept racial prejudice, she will be shown up as his inferior-which she actually is. The play ends with Ella triumphant and secure in carrying out her neurotic pattern of receding back to childhood. Thus she solves the conflict between her desire for a child and her hatred of bearing a child whose father is black. And thus she also effectually keeps Jim from leaving her and escaping to an environment where he can succeed and be happy. The moral to be drawn from All Gods Chillun Got Wings, is retrogressive and reactionary, and the apparent open-mindedness of the author makes it even more so.

But O’Neill is unwearied in his quest. If nature yields no satisfactory solution for human society, there is the flight backward to the romantic past of actual history. O’Neill has written two historical costume plays. The first of these, The Fountain, is a weak play, judged both as drama and as poetry. Yet because of its weaknesses, it conceals less and the symbols are easier to decipher. Ponce de Leon, Spanish conquistador, forsakes a life of conquest and governing to set out in search of the lost fountain of youth. The quest for his lost youth leads Ponce de Leon into an ambush prepared by the Indian chief he has tortured. Kneeling at the supposed fountain, de Leon sees his aged face reflected back and falls to the treacherous dagger. He loses his illusions along with his youth and finds a sorry consolation in the knowledge that the new generation will carry on.

In Marco’s Millions, O’Neill essayed a satire on the American Babbitt who knows what he wants and gets it. But O’Neill’s humour is saturated with sentimentality worthy of Babbitt himself. Marco sets out for the empire of Kublai Khan to enrich himself and his brothers. He comes, he sees, he conquers all the material riches of the emperor. But Marco has never had a soul and when the greatest prize of all, the love of Princess Kukachin, symbol of beauty, is offered him, he passes by unaware and unmoved. The princess so slighted marries a potentate and dies slowly of disillusionment, and Marco, who has guided her to her new kingdom, returns home to Venice to wed his bride and to surfeit in riches. But the death of beauty makes Marco’s triumph a hollow one, for a death of the spirit is worse than a death of the body, O’Neill seems to imply. Therefore happiness cannot lie in the material prosperity of the American bourgeoisie.

IV.

Again O’Neill is undaunted by the failure of his historical quest. If the farm, the sea, the jungle, the romantic past offer no happy solution, there is one refuge praised by all the romantics passionate love between man and woman. Early in his career, O’Neill chose this theme in a play which failed in production. Romantic love in The Straw keeps a sick girl alive and gives her hope in life. But that romantic passion is no more than a straw, O’Neill demonstrated later in another play which was never popular. Welded sets forth the conflict between passion and the individual ego. Michael, an oversensitive intellectual, and his wife, Eleanor both demand that marriage allow them individual expression. When it does not, they try to separate but find that passion has welded them together. With or without personal happiness, they are doomed to remain together. Welded is in no wise as convincing as its great model Totentanz and Strindberg has wrung deeper values from the sex struggle.

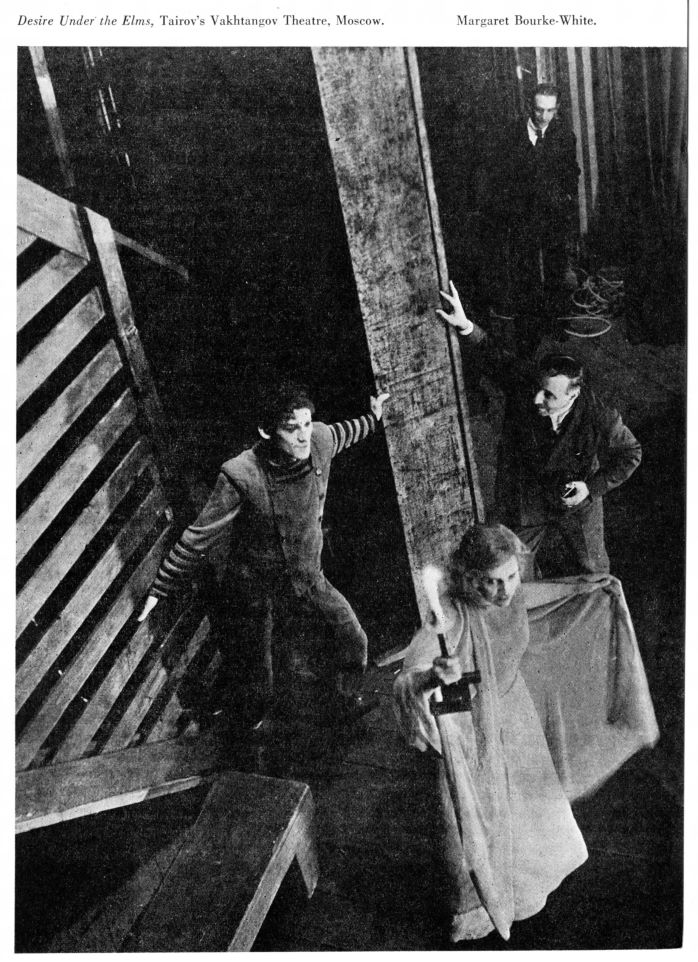

Desire Under the Elms is O’Neill’s best play of romantic love, perhaps because other themes are interwoven with this leit-motif. Two rivals, for the old New England farm of Ephraim, are his young son, Eben, and his newly married wife, Abby. Abby is a realist who wants her corner and security in the world and will wrest it at any cost. When her step-son Eben stands in her way, she determines to have a child by him and to pretend to Ephraim that it is his own. But an unexpected factor is the sudden passion which develops out of the relationship between Eben and Abby and sweeps them to destruction. To prove that she has no longer has a desire for the property and that she genuinely loves Eben, Abby kills their child. Eben overwhelmed with grief, summons the sheriff in revenge. But when he sees the law parting him from Abby, he relents and accepts his equal guilt. Victorious in their love, they go to accept justice. In its psychological pattern, we have a close analogy to Ibsen’s Rosmersholm, where the stranger Rebecca West, having taken possession of Rosmer and his home, even to driving his wife to suicide, is overcome in the moment of success by Rosmer’s ideas of guilt and expiation. So the girl Abby, who was unhampered by moral scruples, instead of killing old Ephraim kills her own love child and becomes a penitent sinner ready to suffer for her passionate love for her step-son. It is the old stern morality of New England which conquers the free spirit of Abby. Desire Under the Elms contains some of O’Neill’s best poetical passages-rich in Biblical imagery and scenes of rural beauty.

The Far Land of the Soul

Midway in his career, O’Neill’s plays are divided into two kinds. The early plays dealt with the external world and its problems–the farm, the sea, the quest for gold, sexual passion, love of power, etc. In the later plays, the action shifts sharply from the world outside to “far land” of the soul.

In this internal country of the soul, secure from such pressing problems as the conquest of nature or of poverty, in a milieu increasingly prosperous and urban, the characters of O’Neill’s later dramas devote themselves to contemplation of their inner lives. The unseen realm of the soul is mysterious and glamorous; it is a country which has already been skillfully charted by Chekov and Schnitzler, European spokesmen of the petty bourgeois intelligentsia. O’Neill now sets off for it on a new expedition in search of his lost happy innocence. The Great God Brown and Strange Interlude, the most mature and complete products of his art, are the treasures brought back from this far journey into the invisible regions of the unconscious over which presides, as Pluto over the land of the shades, the great psychologist of the decaying bourgeois class, Sigmund Freud.

O’Neill’s journey was not however a scientific expedition which brought new data of universal value to human conduct. Using Freud’s charts to find his way in the land of the unconscious, O’Neill has actually explored only the outlines of a neurotic pattern common to the petty bourgeois intelligentsia in the United States.

O’Neill’s use of symbols and of masks and other allegorical devices is often confusing; the meaning behind them has not been fused into a universal meaning which can arouse emotional response in multitudes of people; they are addressed to a small audience of bohemian intellectuals. O’Neill’s invasion of the unconscious was a continuation of his old quest for happiness and love. But love has ceased to be, as in the Desire Under the Elms, a physical passion; it has become a metaphysical presence containing subtle under and overtones plucked painfully from the heart strings. Love has been dissected into its constituent parts, in order to more minutely analyse its essence. There is sensual love, soul love, intellectual love, and the love of God and each of these has its variations and gradations like the changing tints of a sunset. Man, in search of the lost harmony of prenatal bliss, gazes into the mirror and beholds his own image reflected, not merely one image but multiple and varied images, as in the looking glasses of an amusement park, each one distorted and different but never the essential soul of himself.

O’Neill’s flight into the “far country” of the soul has its cause in the actual world. Is it not analogous to the escape of art in the same period into the world of the abstract? Profound social causes underlay this trend in America. It had occurred in Europe somewhat earlier. The fact is that the middle class intelligentsia, chief creator of the bourgeois arts, had been deprived of a major economic and political role in society. Hence unable to function normally in the body politic, it was forced to create a world of its own, where in fantasy it could assume supreme power. It thus promulgated the theory of the freedom of the creative artist; it isolated that artist in an ivory tower far above the dust and tumult of the political arena. It jealously guarded his mythical freedom, which was in reality an exile, and pretended that it was desired when it was actually enforced by external circumstances. The sincere bourgeois artist was imprisoned in the tower to struggle there with his own internal conflicts; thereby he was prevented from discovering the social conflicts which were the primary cause of his own psychic disorders.

O’Neill, like all sensitively aware artists, has suffered greatly from the splitting of the world into two opposing planes-outside and inside. His plays mirror the dualism of the position of the bourgeois artist perfectly. Because of this dualism, which he has sought to visualize by the use of devices such as the mask, the aside or the actual splitting of a character into two roles, his dramas have never attained to the heights of great tragedy. Another playwright who has been obsessed with the same problem–a most acute problem for the petty bourgeois intelligentsia—is the Italian Luigi Pirandello. He has externalized it in terms of reality and unreality and used theatric devices with more adroitness and philosophical slight-of-hand than O’Neill. That his slight-of-hand should land him in the Fascist camp can be no surprise.

O’Neill’s characters throughout remain two dimensional. The problem of experiencing depth and space in the graphic arts is closely akin to the problem of the will in the drama. The heroes of Shakespeare’s tragedies are men of power and action, their wills in conflict with real obstacles. The mad Lear on the heath in the storm evokes a scene of tremendous perspective both in the spiritual and in the actual world. Content and symbol are fused in one complete unit. In the whole theatre of O’Neill, we must search to find one character delineated with a strong will, striving to attain a specific end. Anna Christie, in some respects the most rounded portrait in all the plays, exhibits a seemingly definite will and a determination to gain her ends. But the last act is fumbled actually the author wrote several endings for it–and it does not seem inevitable. Anna’s marriage to the Irish sailor does not seem to solve her problem or fulfill her complete desire. Abby’s strong will in Desire Under the Elms is broken by her discovery of love. Marco Polo alone seems to set out for a goal and to attain it; but it is a shallow and meaningless goal which the author condemns and abhors.

V.

In O’Neill’s plays, life divides itself into two planes–the material world, which he represents as base, greedy for gold and power, shallow and dull; and the unseen world of the soul where he depicts man struggling for higher values and failing gloriously. Now the actual world’s prizes of gold and power are sour grapes for the petty bourgeois intellectual, who must content himself with the shadowy realm of the soul. Here he is allowed untrammeled freedom to conquer “higher and better” values. Here he may assume the masks of power and nobility, but in his heart he is aware all the time that what he really desires lies across a forbidden wall. In the O’Neill theatre, the Babbitt the successful bourgeois, is the fool and the villain; the dreamer who fails nobly, is the hero. At bottom, the dreamer is actually the Babbitt too, albeit an unsuccessful one. And the hero-dreamer’s revolt is doomed from the start to futility, for it is based on flight.

One of the most moving of O’Neill’s plays, The Great God Brown contains passages of profound insight and poetic tenderness. Yet it contains no solution to O’Neill’s quest. Therefore he takes revenge in depicting the Great God Brown or Babbitt as envious of the artist-dreamer, Dion-Anthony. Dion, dying, wills to the Great God Brown his tragic mask–his noble aims and dreams. This mask poisons the life of the Great God Brown; he ceases to be content with his material soulless existence and he craves to win the love of Margaret, the ewig-weibliche soul of woman.

Babbitt is defeated by the Bohemian artist; he is forced to accept the artist’s values; he, too, develops a soul–and his soul becomes the source of Babbitt’s bitter discontent with the cheap, material paradise of his worldly success. In the end, the soul of the artist Dion takes possession of the Great God Brown and destroys him. This modern miracle play externalizes the conflict in the soul of the petty bourgeois intelligentsia.

As a fable of the decay of present society, the play is truer than O’Neill perhaps intended; as theatre, it remains confused, the action will-less, emotionally unsatisfactory. The playwright is himself uncertain about the meaning of the dramatic symbols and the conflict which they present. All the O’Neill heroes are divided against themselves and are therefore incapable of absorbing the outside world in its depth and complexity; hence they never experience life in its fullest. Their eyes are always filled with undeciphered dreams. Yet they keep passionately affirming how they have loved, lusted, and lived. As a matter of fact, they have been so pre-occupied with their internal problems that they have not even glimpsed the world of living reality.

As a foil to these hero-dreamers, these introvert knights of the nocturnal soul, O’Neill sets up a series of so-called ‘normal’ people— Sam Evans, Marco Polo, Billy Brown, Peter Niles. Seen through the introvert eyes of their creator, they are nothing but lay figures, shallow, stupid, dull, immature. Yet, in order to be just, or perhaps for the sake of good theatre, he always portrays them as “good.” In Strange Interlude, O’Neill has attempted to come to grips with the unconscious. The aside is used to reveal the internal life of the character. Planes of existence assumed to be parallel and contradictory are externalized by the aside, just as they were externalized by the use of the mask in the Great God Brown. There are flashes of beauty and deep insight in this play, but during nine unwieldy acts, lengthened by the asides, which actually reveal nothing which could not have been dramatized in the action and conscious dialogue, the plot stagnates. O’Neill presents us with a beautiful neurotic heroine, Nina Leeds, whose passionate quest for fulfillment in love is the main theme of the drama. But this quest ends in a smug hanging on to comfort and contentment. Nina’s life becomes shallow, worthless, meaningless; her only contribution to life is her illegitimate son, Gordon, palmed off on her husband by her lover and herself, in order to keep the husband “happy.” He must be kept “happy” because he is so “good” and, above all, because he is “successful.”

Nina’s life is uncreative in every respect. Not one of the men with whom her life becomes entwined receives anything from her. Sam, her husband makes money in spite of her. Darrell, the lover, neglects his work as a scientist and physician, to hang on to her apron strings. Marsden, the old-maidish platonic lover, accepts her in place of his mother. Not one of these men is able to make a satisfactory and definite decision in any crisis. Whenever any character in the play acts, the action is usually one that would never be dictated by common sense or realistic aims. Nina’s whole life is a series of decisions which complicate existence without helping anyone. They are supposed to be motivated by noble aims, but only because they deprive her of what she really wants. After her husband’s death, when she might marry her lover, she prefers to drift into marriage with Marsden. This will enable her to spend the rest of her life doing nothing in a New England garden, while waiting for death to liberate her from a death-of-the-spirit as complete as Marco Polo’s, who never had a soul to worry over. The emptiness and superficial character of the society portrayed in Strange Interlude becomes most clear in the boat race scene of the last act. Yet O’Neill does not look at his characters with a critical eye or analyze their threadbare ideals. If, like Ibsen in Hedda Gabler, he had laid bare the tragedy of a willful and beautiful woman whose only choice was in a barren marriage, the material might have been interesting. But in the twenties in the United States, there were many choices for a woman like Nina Leeds; we must assume that she preferred a loveless, secure marriage based on deception to facing the full implication of her passion for Darrell. We are therefore unmoved when all the characters are assembled for a grand climax to see Nina’s son Gordon win a collegiate boat race! There is no action at all, for the characters have wavered so long, that life offers them nothing but disillusionment as experienced by Darrell or the idiotic enthusiasm for puerile school boy matters that satisfies Sam.

Other playwrights have dealt with such aimless and actionless people and made drama out of their inertia and neurotic fears, but O’Neill does not step back far enough to see these people against their social background. Never are they as vigorous as the flesh and blood creatures of The Cherry Orchard. Never do they think beyond themselves of the problems of their fellow-men. The idealistic Three Sisters suffered more genuine pangs of soul in their provincial exile than do O’Neill’s moderns on the decks of yachts, on top of penthouses in the metropolis or wandering on the Away from Reality clipped lawns of Long Island estates. Of what use to visit the fantastic world of the unconscious when the secrets brought back are no more valuable than this dried seaweed of desire and these broken shells of lost hope? O’Neill has found no buried treasure in this Saragossa sea of the soul. This is cheap dross like the treasure sought for so many years by the hero of Gold, who knew all the time that what he was seeking was brass.

VI.

Perhaps O’Neill has surmised that for all his inimitable diving, he has brought up only brass; from now on, at least, he forsakes the invisible world of the unconscious and attempts to enter the real world of modern times, which has been made and moulded by the industrial revolution.

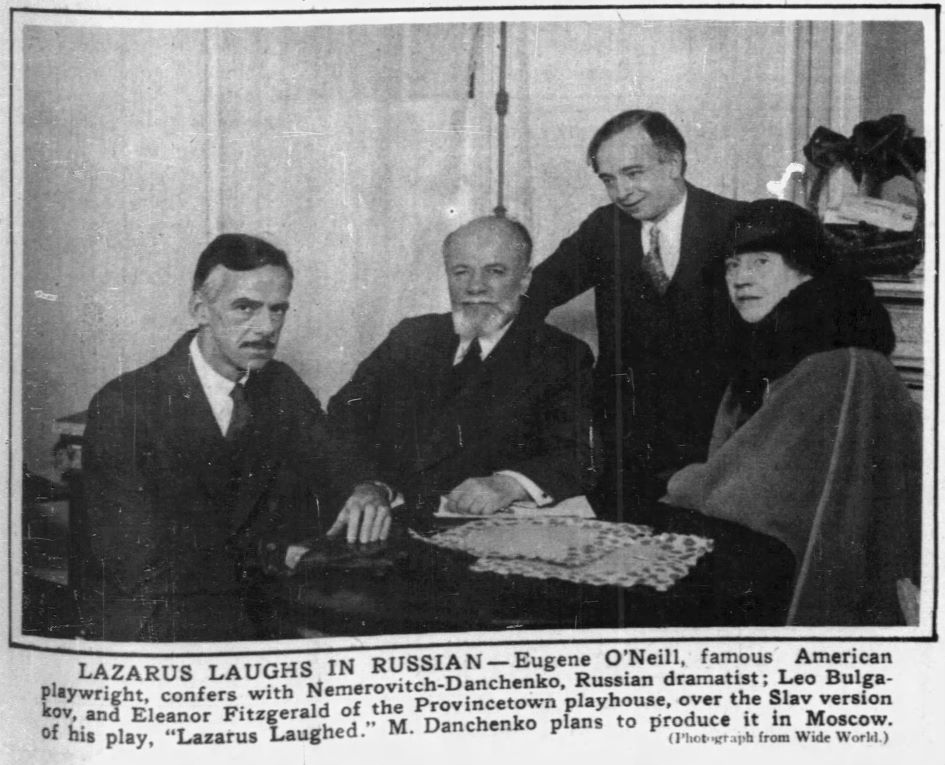

O’Neill’s quest led him to turn to the machine age. This may have been a reaction from the immediate post-war period, when the American intelligentsia, echoing a kindred mood in Europe, revolted against the machine. The too sensitive souls of Babbitt’s sons fled to exotic countries and became expatriate. The stay-at-homes built their Bohemian shelters against the standardized society made by the machine. But as prosperity increased and the petty bourgeois intelligentsia profited by it, they became more reconciled to the machine, which brought blessings to them as well as to the big bourgeoisie. Poets like Hart Crane were pioneers in building bridges from the world of traditional poetry, whose images stem from an agrarian. world, to the new world of industry as yet unchartered in the poet’s geography. Sensitive to these reactions, O’Neill essayed to write a play showing the machine as a moloch. He dramatized the conflict in a series of abstractions. In Dynamo, the machine is presented as a monstrous god, jealous, relentless demanding of his followers in return for services rendered absolute faith and the sacrifice of all instinctive desires including love. While employing modern symbols like hydro-generators O’Neill actually speaks in the accents of the pre-industrial myth. If he had visualized the machine as life-destroying in the hands of exploiters, as useful in the hands of producers and workers in society, the myth might have had modern connotations. But the story of Reuben Light, his conversion to atheism, his murder of his sweetheart, his self-immolation on the machine solved no problems for anyone. The story had no application; it was merely a study in psychopathology. Hence Dynamo remains a meaningless fable, unless one is supposed to deduce that chastity and atheism are fundamentally necessary to the control of the machine. Dynamo has no more real roots in the modern world of reality than has the pseudo-Biblical-classical drama Lazarus Laughs.

The plays now show an increasing inability to face reality altogether. They indicate a desperate need of an escape; and carry their quest into another world of shadows, a world beloved by the romantics–the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome. This turning to the dream of the golden age enshrined in poetical tradition indicates an end to rebellion, a return to more conventional paths.

Although O’Neill has forsaken the Hades of the unconscious depicted in Strange Interlude, he has not left behind Freud’s prescriptions. He applies them now to interpreting the classical Hades, where dwell the pursuing furies of man’s guilt. He chooses the Electra myth made modern by Freud’s famous complex to write a classic trilogy in the manner of Attic tragedy.

Mourning Becomes Electra sets forth the tragedy of a decaying New England family in the period following the Civil War. The trilogy divided into three full length plays–The Home Coming, The Hunted, The Haunted closely follows the story of the doomed house of Atreus.

The classical legend recounts how Agamemnon, leader of the Greeks, returned from Troy and was murdered by his wife, Clytemestra and her paramour, Aegisthus. The killing was an act of revenge for Agamemnon had sacrificed Iphegenia, Clytemestra’s youngest daughter to assure Greek victory over Troy. In return Electra and Orestes plot and carry out the murder of their mother and her paramour to avenge the murder of their father.

Attic tragedy based on this legendary history contains implications lost to modern audiences. For the Athenian spectator, the plays of Euripides and Sophocles had a meaning far beyond any single family tragedy of blood; they were ritual dramas whose choruses recounted the social history of the Greek race and celebrated a tremendous legendary event-the transition of a Greek society from the matriarchal forms of the Orient to a newer society based on man’s domination through the city state. Greek drama enclosed a whole world with a religion and ethic of its own, dominated by the idea of inevitable fate. In Attic tragedy, murder was not conditioned by mere personal pique or revenge, but by far wider social issues. Clytemnestra, killed because she did not accept the mores of Thebes, and because she could not forgive her daughter’s sacrifice for a cause she did not believe in. She personified an older form of society in which woman was not yet relegated to the family hearth alone. But her children, Orestes and Electra, belonged to the new order and they had been deprived of social position by the murder of their father, the king. Clytemnestra’s crime was not the killing of her husband but the destruction of the head of the state. Electra’s act was dictated by the need to obtain her portion of power and her brothers in the city state. Here passion is inseparable from politics.

Athens and Broadway

O’Neill has built his version of this tragedy on purely personal motives without any profound social significance. Despite its mastery of a brooding, decadent mood, his trilogy remains merely the chronicle of the crimes of a New England family. It could, perhaps be interpreted as a study of the decay of the puritan mores in contact with pagan ideas; but it is so individual a tragedy that it has no general application to American life. Its inept chorus of New England small town folk is merely an extraneous decoration in the archaistic fashion; it adds nothing to a tragedy which in itself is not inevitable. In the reconstruction period, it was not necessary for Christine (Clytemnestra) to murder her husband, the returning general, in order to commit adultery, nor does Lavinia (Electra) need to murder her mother’s lover and drive her mother to suicide, in order to find her place in the sun. She could easily have gone away and married or, if she desired her mother’s lover, there were other means of revenge. More normal alternatives of action were open to all the characters than the one they chose of murder and blood or which their author chose for them, in mechanical imitation of the Attic pattern. O’Neill’s tour de force makes the characters too abnormal and different to awaken either pity or terror in a modern audience. Their demise occasions not regret but belief. The real purpose of tragedy is thus forfeited. Mourning Becomes Electra remains an archaistic nightmare of the golden age.

It is conceivable that a dramatist might achieve an effective tragedy of fate with a modern setting but O’Neill’s trilogy does not achieve it.

The glory that was Greece becomes one more blind alley on the road to happy innocence. More elaborately constructed and technically more concentrated than his early plays, the implications of the trilogy are less vital and less emotionally exciting.

VII.

From pseudo-Attic tragedy O’Neill reacted by writing a successful Broadway comedy. This was scarcely his intention, but Ah, Wilderness is a play uncorroded by the bitter acid of pessimism. In it, O’Neill has succeeded, for the first time in creating characters in three dimensions with the juice and savor of actual people. It is a boyhood comedy of happy youth placed in America in the halycon days of 1905-long before the world war and the economic crisis in another golden age now vanished forever.

But what does O’Neill choose to reveal as the “real life”? He depicts a Babbitt family in a small town; with approving good humour, untinged by criticism, he delineates the smug, conventional, everyday life of these people with round of church socials, Fourth of July picnics, movies, small gossip, drink and repressed sex a typical Grant Wood painting of American “national” life.

In this Main Street, from which at the beginning of the twenties, all the Carol Kennicotts revolted, from which O’Neill’s own rebellious dreamers fled to sea, the playwright settles down with a good natured, middle aged shrug of acceptance. Like Emperor Jones, he has gone around in a circle and has come out of the jungle at the same place he started from–the Main Street of Zenith with its Babbitts. Only a decade before, he had slammed the back door of respectable middle class society, and like Ibsen’s Nora had gone forth to see the world. Now he has returned, a contrite prodigal in the well pressed clothes of success to be admitted with honor into the front parlor, there to repent at leisure his associations with outcasts, sailors, workers, prostitutes, Negroes, free women, artists.

The dreamer O’Neill has capitulated to the Babbitt O’Neill thereby reversing the story of the Great God Brown. Back in the fold of middle class society, O’Neill embraces the most obvious, bigoted conventions of his class, and exhibits an intolerance, which a cultured, bourgeois advocate of the status quo who has never questioned the fundamental postulates of capitalist society would blush to admit.

It now becomes quite clear that O’Neill’s original revolt from middle class standards never involved a real break with bourgeois society. Rather it was an adolescent upheaval, a flight to Bohemia common among the youth of the middle class, usually ending in a return to the conventional grooves of society. Every one of O’Neill’s plays, read in the light of his total developments, exhibit signs of a conflict never resolved. This was no other than the conflict of the petty bourgeois intelligentsia prior to the present economic crisis, when it had not yet found a political role, when it hated the big bourgeoisie and yet hated to be pushed down into the ranks of the proletariat. O’Neill was the spokesman for this tragic dilemma of the petty bourgeois intelligentsia which in the end will be compelled. to choose between Fascism and Communism. It is for this reason that his characters exhibit the split will, which destroys the unity of drama. The duality of his characters is forced on them by their position in society.

With Ah, Wilderness, O’Neill solved the conflict for himself by returning to the status quo. He thus regained the audience, which he once forsook. But what effect has his capitulation had on his art? Exhausted in will by a sterile quest, he has become incapable of any action significant enough to create drama.

The plot of Ah, Wilderness is so petty that it scarcely sustains the burden of the action. For over two hours we witness the spectacle of an old maid and her bachelor friend, engaged for years to marry, and again deciding not to marry; we witness the sorrows of an adolescent boy, who because of his “radical” ideas, loses his childhood sweetheart and rebels against home restrictions, gets drunk, almost sleeps with a tart, and returns to the narrow path of duty and prospective conventional life and marriage.

There is no struggle, no action, no plot and no ending. There is however homely humour and well-worn successful theatrical devices. Life has become so static that O’Neill’s drama dies of sheer inertia. There is not even the suggestion that beneath the shallows of this everyday life, a more significant drama exists which might be called forth in a crisis, as there is in the drama of Chekov and Schnitzler. If “wilderness were paradise enow” it is a dull vacuous paradise bought at the price of imagination, thought, and action–a hades worse than the medieval conception of hell. Now the tables have been turned: the Great God Brown has given his soul to Dion Anthony. Truly did Proust observe that in the second half of his life, a man is often the opposite of what he was in the first.

Huysmans, on completing that bible of decadence, A Rebours, said: “After such a work, one of two things were open to me–either the muzzle of a pistol or the foot of the cross.” This is the dilemma that now confronted O’Neill. Over-sensitive, burdened with nostalgia, his color-loving, lyric soul could never submerge itself completely in the Babbitt ranks. He might put on the mask of Babbitt temporarily, but even the Babbitts would not be fooled. They would never accept him as one of themselves. O’Neill’s quest has led him ever along a path of retrogression; now he has no other alternative but the church into which he was born. By returning to it, he returns to his mother and to that perfect love which could not be found elsewhere in the world. Hence it was inevitable that Ah, Wilderness should be followed by Days Without End, a miracle play of escape from the terrific dilemma of the middle class intellectual in American society today.

Farewell to Life

O’Neill is above all a sincere artist at the height of his maturity; he has felt the full impact of this dilemma, but he has evaded the responsibility thrust upon him in his role of spokesman and artist of the petty bourgeois intelligentsia.

Like so many others, including the distinguished author of The Waste Land, O’Neill has sought shelter in the violet shadows of Catholicism. Days Without End can scarcely be termed a play. Rather it is a public confession, a final melodramatic gesture of hopeless terror. The poet discarding the mask of the Emperor Jones, Yank, Marco Polo, Ponce de Leon, the Great God Brown, Lazarus, Eben Cabot, Lavinia, Nina Leeds, and falling like a contrite child before the altar, cries out of a broken heart–“O son of man, I am Thou and Thou art I. Why hast Thou forsaken me?”

So sharp has become the conflict in O’Neill’s soul that he has divided the hero of Days Without End into two people to be played by two actors. John and Loving are two halves of the same personality split apart–a modern Faust and his Mephisto. They are doomed to struggle against each other in a deadly duel, yet the plot chosen to set forth this internal combat is puerile and dull: it concerns itself with the material of all parlor drama, domestic adultery; the action has become even more static than in Ah Wilderness. A frayed plot depicts how John Loving makes money for his adored wife while trying to satisfy his repressed creative urge by writing a novel of his problems. In this age of crisis, we are invited to the voluptuous soul writhings of a hero in a luxurious duplex apartment over the “enormous” offense of a casual and momentary adultery, from which even pleasure was absent. At the moment, there arrives a long lost relative, a fatherly priest, who takes over all burdens. When John Loving has driven his wife to the verge of dying by indirectly revealing his great crime, he promises to be good and join the church, if she is saved by his prayers.

Art and Propaganda

There is something obscene in this hero’s preoccupation with sex and soul, reminiscent of the Russian intelligentsia in the decadence following the defeat of the 1905 revolution. During that reaction, there occurred the same mystical vaporings and swoonings in the arms of the church, a church which at the moment was helping to organize the gangs of Black Hundreds to terrorize and kill the Jews and the workers. So in 1930 in New York City, we observe John Loving, over after dinner coffee impeacably served, politely give up his last gesture of revolt. In the world-duel between the priest Baird, who stands for the most obvious and reactionary elements in the Church, and Mephisto-Loving, the play reaches its climax–a climax infected with the triteness and inaction of a bad propaganda tract. How odd that these authors who always demand the divorce of propaganda from their sacred art should be the first to commit the offense they decry, and without any subtlety whatsoever!

The split personality of John caught between the shafts of his alter ego, Loving, and his friend, the Priest Baird, delivers himself of this argument:

“Freedom demands initiative, courage, the need to decide what life must mean to one- self. To them (most people) that is terror. They explain away their spiritual cowardice by whining that the time for individualism is past, when it is their courage to possess their own soul which is dead–and stinking. Oo, they don’t want to be free. Slavery means security of a kind, the only kind they have the courage for. It means they need not think. They have only to obey orders from owners, who are, in turn, their slaves.”

These are the ideas of Dostoyevsky’s Grand Inquisitor, diluted and weakened. Here O’Neill pronounces verdict on himself, who has evaded the issue facing every intellectual in America today, whether he be a writer, painter, musician, or professional worker. The bourgeois intelligentsia, along with the workers, must face all the implications of the present crisis.

Europe’s recent political history indicates the fate of the American petty bourgeois intellectual in the future. Until now, the intellectual had a choice: he might take a stand with the working class and their fight for freedom or he might retire into his ivory tower and hoist up the drawbridge in order to contemplate culture remote from the raging class conflicts. As the crisis deepens, the intellectual in order to live is compelled to abandon neutral territory. In the battle of the classes no man’s land becomes untenable. To remain in the ivory tower demanding democracy and freedom, when these ideals are being destroyed all about us, is to take sides with decaying capitalism. To attempt to evade the issue is to tread the path of fascist sterility. Despite all pacifist and humanitarian principles, the liberal intellectual will have to orient himself in the coming struggle for power. Otherwise if he does not perish physically, he will perish in the spirit.

O’Neill cannot evade the issue. Hiding in the church, he lies in the house of reaction. His hero John declares: “We need a new leader, who will teach us that ideal, who by his life will exemplify it and make it a living truth for us. A new savior must be born who will reveal to us how we can be saved from ourselves, so that we be free of the past and inherit the future and not perish by it.”

John chooses the church and its security; his Mephisto twin, Loving, dies at the foot of the cross. But this cross is merely a way station for the petty bourgeois intellectual. The church is unable to solve the enormous economic problems of the world today. The choice can only lie between Fascism and Communism. Either society must be changed or it must go backward into chaos and reaction. The split that is already occurring in the ranks of the petty bourgeois intelligentsia in America is fast losing O’Neill his audience. He was the leading dramatist of the twenties when the American bourgeoisie was the successful Marco Polo, economically prosperous, spiritually dead. Envious of the upper classes, contemptuous of the proletariat, and distrustful of itself, this class sought solace in sex, psychoanalysis, alcohol and art—an art as remote from the reality of its own life as it was from the social reality as a whole. O’Neill was the poet of this class in the twenties. Today the petty bourgeoisie is making its choice between the capitalist mirages of the moment and the camp of the proletariat. There is a great, living, grateful, and thrilling audience awaiting those creative artists who choose to stake all for a new creative world. Out of the struggle for that world must necessarily stem a new and vital art, such as America has not yet dreamed of, but this art will move in a direction opposite to O’Neill’s hopeless quest for mystical peace.

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v2n09-sep-1935-New-Theatre.pdf