Bingham Canyon, Utah–home of the Utah Copper Company–a profitable paradise for capital, hell on earth for workers.

‘Bingham Canyon’ by W. G. Henry from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 13. No. 4. October, 1912.

SINCE reading Frank Bohn’s article on Butte, the great copper camp, it has been on my route to visit the “Little Kingdom of Copper,” Bingham Canyon, Utah. Comrade Bohn has interestingly described the benefits accruing to the worker through their political and industrial organization in Butte. The main purpose of this article will be to Show the contempt, the poverty, the disregard of their lives and welfare in which the workers in the same industry are held by their masters because of a lack of industrial and political organization here. Bingham Canyon is twenty-five miles from Salt Lake City in what is known as the West Mountain District. In the camp are living perhaps 2,500 people. Within a radius of three miles from the post-office 5,000 men are working in and about the mines. It is an open shop camp. Greeks, Italians, Slavonians, Finns and Hungarians with a sprinkling of English speaking workers are employed. Of course the mine owners see to it that the fires of race antagonism are continually replenished. The Finns dislike the Greeks, the Greeks look askance at the Slavonians, the Slavonians are distrustful of the Americans and the Americans proudly flout the whole batch of “ignorant foreigners” and stand on their American birthright and supremacy. But be it known that Greek, Italian, Slavonian or American each and every man, of whatever race, gets precisely the same pay here for the same work. There is no race supremacy on the payroll of the companies in Bingham.

The day here consists of eight hours for men working underground—and it is every bit of eight hours and for outside men—the great majority are outside men in this camp—the day is ten hours. The wages are: Common labor, $2.00; muckers, $2.50 to $3.00; machine helpers, $3.65: machine men, $4.00 per day. The principal mining interest is the Utah Copper Company, employing about 3,000 men. Average board costs one dollar per day. The cost of living is higher than Butte, the hours longer and the wages lower. Copper is now quoted at 17 to 18 cents per pound, yet the scale of wages in Bingham remains the same as when copper brought nine cents a pound. But what can the workers expect when they are unorganized? Some of the wise ones are predicting that if copper goes higher the companies will voluntarily grant a twenty-five cent increase—merely to lull the slaves into repose.

There is another side to all this, of course. In order to grasp the situation in all its bearings let us put on capitalist spectacles and get the “business” viewpoint of Bingham. Along with their spectacles we’ll take the capitalists’ own statements. In the Salt Lake Tribune of August 8th the Utah Copper Company publishes its statement for the quarter ending June 30, 1912, from which I quote the following:

The Utah Copper Company on Wednesday released the report for the quarter ending June 30, 1912, and from the details of the same that came west during the afternoon it is evident that this famous premier copper producer of Utah and all the country has eclipsed all previous records, striking during the period a splendid gait by virtue of increased copper production and increased market prices for the metal.

During the quarter the company produced 28,372,038 pounds of copper, an increase of 3,442,488 pounds over the previous quarter, the cost of producing the metal being 2.127 per pound, against 8.62 cents during the previous period. The company received for its metal an average of 16.43 cents per pound.

Now carefully remove the bifocals of the master class and keep your working class eyes wide open. It is not alone in the fact of low wages and colossal profits nor in the pitting of race against race, nor yet in the brutalizing of these workers that the tragedy of capitalism becomes abysmal, but it is the toll of human life in the production of the profits required by these copper kings and barons that is appalling, almost unbelievable.

Comrade Bohn informs us that in Butte last year forty-seven miners were killed at their work. What would the miners of Butte, what would you say about a locality employing only 5,000 men in which last year 440 men were killed during their work? But then remember the workers in Butte are industrially and politically organized, while in Bingham they are not. These killings are so common that they excite no comment whatever. Their frequency has brutalized the working class along with their masters.

“Oh, yes’ they bump ’em off every day, my workingman friend replied when I touched on the subject. “More than one a day goes over in this camp, mostly foreigners and of course they don’t count. How many are crippled? I doubt if God knows. See this fellow coming down the road minus an arm? That arm has been off less than thirty days. See that fellow over there on crutches? Rock fell on his foot last week. Oh, what’s the use? You can see’ em everywhere. I only know the history of the Americans’ accidents. I don’t pay any attention to these foreigners and they are the main ones who get hurt. “There’s no kind of record kept of accidents.”

While my friend and I conversed we toiled up the narrow canyon—he on his way to the night’s work, I to see and hear what might be of interest. My sight of the crippled and outworn soldiers of industry was disturbed by the sound of the prolonged boom! boom! of blasts in the struggle of men against Nature. Far up the towering mountain side were the forts, the batteries and the soldiers to be used in case of any industrial disturbances. Below in the narrow gulch were the killed and crippled heroes of the army of Labor, while far from danger in their clubs and hotels smugly and contentedly lolled the commanders of this army—the so-called captains of industry.

There is no law in Utah requiring coroner’s investigations of mine fatalities. An attempt was made in the last legislature to enact such law, but Governor Spry vetoed it after it had passed both houses. This nimble jumping-jack of the mine owners (Spry Bill) explained his conduct by saying such a law is unnecessary as mine accidents are rare and this law would entail needless expense upon the state and open up avenues for reckless damage suits against the corporations. Militant workers give this spry sprig of capitalism credit for his bold, bald frankness.

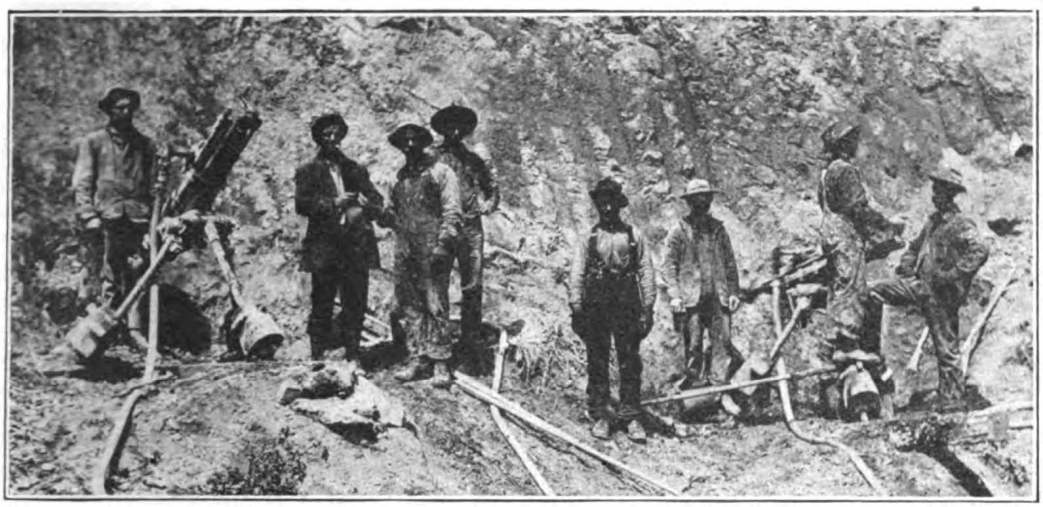

The property of the Utah Copper Company cannot rightfully be called a mine nor can its operations be called mining, at least not as mining is generally understood. Its property is a mountain and its operations consist in blasting down that mountain, loading it into a railroad train and shipping it to the smelter, there to be transformed by a certain process into copper and by a certain other process into gold. This “mine” is inverted, the apex being the top of the mountain, the various levels are marked by a regulation railroad on which are operated freight trains, hauling away the rock. Every hour of the twenty-four, every day of the year, machine drills are piercing holes in this mountain side, dynamite 1$ tearing greater caves and loosening up vast quantities of ore. Steam shovels load this ore into box cars at the rate of one car of sixty tons in five minutes. That’s going some and you’ll have to go some more to find a mine to beat this one in production and methods. Experts claim that this “mine” has $200,000,000 worth of ore in sight.

From a “business” viewpoint Bingham is certainly a paradise; from the worker’s viewpoint it is—hell.

But the light is breaking. The Sleeping Giant in Bingham is beginning to stir in his slumbers. Slowly but surely the “muckers” who produce the copper are having it burned into their brains that they are getting the worst of the bargain and that somebody is somehow getting the best of them. Mass meetings have been called of the workers in and about the mines. Hundreds of workers have responded. Race prejudice is beginning to break down and a glimmer of class solidarity is apparent. “One union for all the workers in and about the mines” is the slogan in Bingham and the future looks bright for the toilers. As I close this article I learn that the mine owners have granted a raise of twenty-five cents per day to all underground men. This is a pittance and will not suffice. But if the least organized can gain such an increase without actual struggle, what could not a powerful organization of the workers in Bingham do? Wait! We shall see!

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v13n04-oct-1912-ISR-gog-ocr.pdf