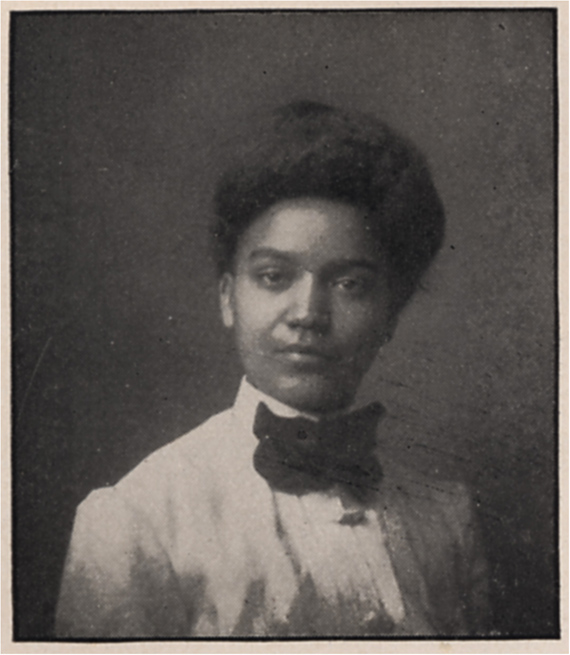

Literary editor of The Crisis, poet, and major figure in the Harlem Renaissance Jessie Fauset with an early biography of an African 48er, ‘the founder of Black Nationalism,’ Martin R. Delany. In an extraordinarily rich life Delany was an educator, an editor and publisher, a revolutionary abolitionist, militant of the Underground Railroad, comrade of John Brown and rival of Frederick Douglass. Pan-Africanist, explorer and diplomat, author of speculative fiction, the highest ranking Black soldier in the Civil War, Freedman’s Bureau officer, politician, and medical doctor, among much else.

‘‘Rank Imposes Obligation’: Martin R. Delaney’ by Jessie Fauset from The Crisis. Vol. 33 No. 1. November, 1926.

BLOOD told in the case of Martin Robinson Delaney, an intellectual giant towering high above many black men of his day. He was the descendant of noble African ancestors, a Golah king on his father’s side, a Mandingo chieftain on his mother’s. The chieftain, captured and brought to this country, lived a life of continuous revolt, fleeing once from the slave plantation in the South to what he considered fondly the fastnesses of Toronto, Canada. Through some tricky interpretation of slave laws he was brought back; but his spirit of rebellion surged on in the breast of his daughter Pati who married Samuel Delaney and bore Martin in Charleston, Virginia, May 6, 1812. This chieftain’s daughter, seeing how scant were her children’s chances for education, convoyed them ten years later, under pretext of moving to a town nearby, to Chambersburg, Pa., where the young Delaney attended school without hindrance.

They had already known the difficulties, in the matter of procuring an education, which were the common burden of Negro children born in the South. The schools of Charleston were of course closed to them; but they had thwarted this injustice by trafficking with wandering New England peddlers who furnished them with the “New York Primer” and the “Spelling Book” and who furthermore gave them instruction in those mystic pages, asking them for nothing except “what ye mind to” and whispering encouragingly that the right to learning was the common privilege of all. It was because of the ill-feeling engendered by these persistently ambitious children in their quest for knowledge at a time and in a place where such knowledge was forbidden by law to people of their blood that Mrs. Delaney found it discreet to leave Charleston.

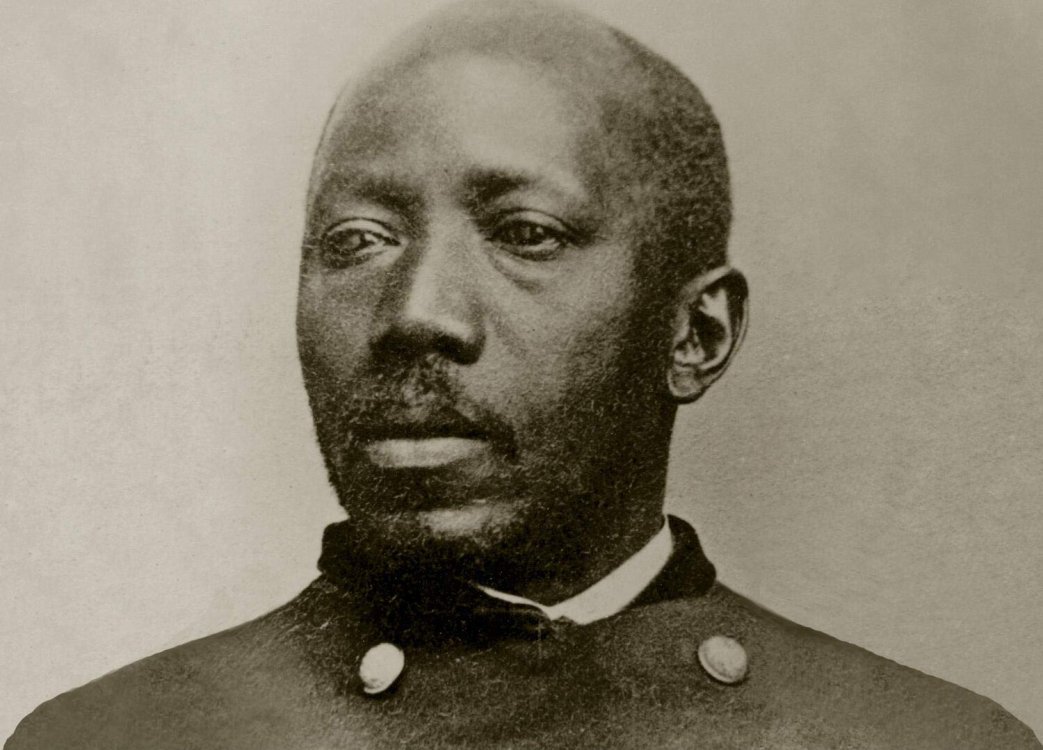

Courage and pride were the first spiritual qualities which the young Delaneys knew and in none of them did these qualities find soil more receptive than in Martin. He grew up proud of his ancestry and marvelously proud of himself. As a man it was his most outstanding quality, transcending even his fine training and experience. He was a perfectly black man, strongly and compactly built, of the middle stature, with broad shoulders built for burdens and of the type which the French call trapu; his head was good and well-poised, his eyes keen and very bright. Everything about him breathed energy, tirelessness, fire and pride. And of this pride his color was the cornerstone; for it signified to him freedom from the debasing humiliation of mixed blood. Rollin, his biographer, quotes Frederick Douglass as saying: “I thank God for making me a man simply; but Delaney always thanks Him for making him a black man.”

Chambersburg of course would not content him. His energies called for a larger field of action. At the age of nineteen then, behold him bidding his family farewell and heading across the state to Pittsburg. Alone he went and on foot! Three ridges of the Alleghanies towered before him but dauntlessly he crossed them and stopping to work for a month at the town of Bedford entered Pittsburg and plunged into its activities. The welfare of his people was his obsession; by 1834 he was engaged in the organization of all sorts of committees for the uplift of Negroes and for the relief of the poor. He founded a total abstinence society and assisted in the formation of the Philanthropic Society, really the foundation of the Underground Railroad, whose executive secretary he shortly became. In spite of the dangers and necessary secrecy involved, he assisted within the space of one brief year in the flight across the border of two hundred and sixty-nine people. Doubtless his connection. with the military helped him here; his protests against mobism and lawlessness had been so vehement that the authorities finally made him a member of the police force especially appointed to serve with the soldiery.

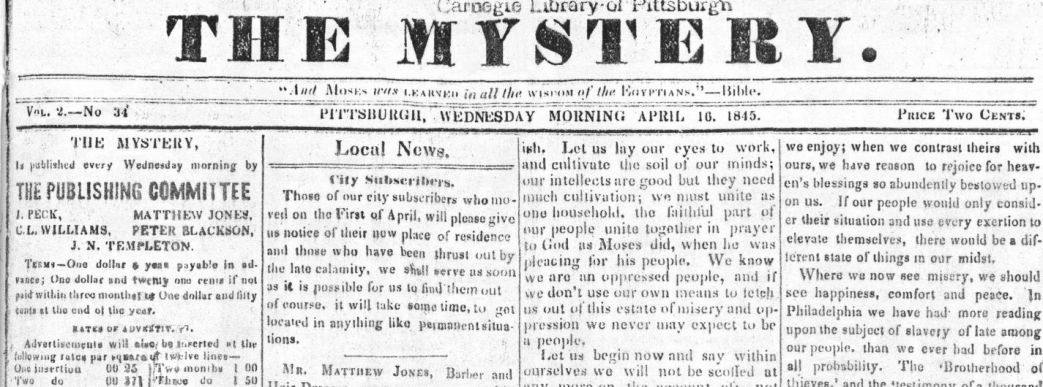

Before long even the limits of Pittsburg proved too confining; Delaney had messages which must be heard. And so in 1834 he edited a newspaper called “Mystery” which he conducted solely from his own resources for upwards of a year. Then he transferred the ownership to a group of six men but remained editor thereof for four years more. Many a stirring editorial appeared in these columns and Rollin thinks that through the influence of this sheet the Avery Fund was originated. The Rev. Charles Avery, stimulated by Delaney’s impassioned plea for resources to meet the social requirements of the colored man, first founded Avery College and on his death in 1858 left “one hundred and fifty thousand dollars for the education and elevation of the free colored people of the United States and Canada and one hundred and fifty thousand dollars for the enlightenment and civilization of the African race on the continent of Africa”.

After successfully editing “Mystery”, Delaney came east for a while and formed a partnership with Frederick Douglass. Together they issued the “North Star”.

All this time this remarkable man, so swamped with cares and responsibilities, speaking and traveling everywhere, had been devoting himself to the study of medicine. His first work was done in the eighteen-thirties under the guidance of Dr. Andrew N. McDowell, but for some reason he desisted for a time and entered upon the pursuit of what one writer grimly calls “practical dentistry”. But his interest in therapeutics never waned and in 1849 after dissolving his connections with Mr. Douglass he resumed his studies under Drs. J. P. Gazzan and Francis J. Lemoyne. As his knowledge and enthusiasm mounted he attempted once more to realize a dear desire of his heart,—entrance into a first class medical school. For reasons of color his admission had always been refused frankly and without veiling by the University of Pennsylvania, Jefferson College and the medical colleges of Albany and Geneva, New York. But finally, his star in the ascendant, he entered through the offices of his two medical friends the portals of Harvard Medical School. That was a great day for Martin Delaney and an even greater portent for his race. Needless to say he successfully completed his undertaking. At its conclusion he traveled for a while lecturing shrewdly and with salutary influence on physiological subjects. So finally he got back to his chosen Pittsburg and settled down to the skillful practice of his hard-won profession. His successful treatment of cholera there in 1854 was remembered for many a day.

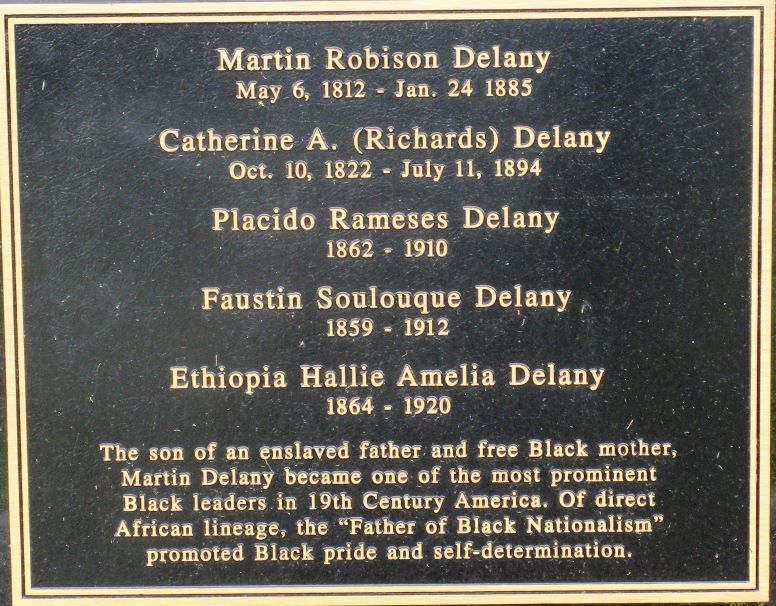

Everything in him yearned for the improvement of his kind. He passionately desired about him evidences of refinement; he loved the Humanities; as a very young man he had devoted much time to Ethics and Metaphysics and his reading was wide and catholic. In our day he might have been considered pedantic, yet paradoxically seen from the perspective of almost a century it is easy for the sympathetic student to understand the impulses which led him, belonging to a group steeped at that time in the very depths of degradation, to exaggerate and over-emphasize evidences of culture in his conversation and daily life. He had married in 1843 Kate Richards, a capable, devoted woman of a prominent and wealthy Pittsburg family. Many children came to the couple and in no respect was Dr. Delaney’s learning and love of learning made more evident than in the choice of names which he bestowed upon these defenseless youngsters. Fancy, to give only a few samples, a household whose members responded to the titles of Toussaint L’Ouverture, Faustin Soulouque and Rameses Placido!

During the early decades of the nineteenth century projects were constantly being offered by the professed abolitionists and other members of the Anti-Slavery group for the amelioration of the vast horde of black men whose physical fruitfulness and political helplessness alike menaced the country: One of the favorite schemes, one meeting alternately with hot favor or frigid disapproval, was a scheme to form colonies of colored people in foreign lands. Of this Dr. Delaney was an ardent supporter. His connection with Africa was comparatively close; he had through his mother and grandfather a distinct feeling of kinship for that distant land. Because of this feeling mingled with his keen pride and love of adventuring into the new and strange, he advocated very strongly the calling of a convention at which the possibility of colonization should be thoroughly argued pro and con. Such a convention was actually held in 1853 at which every delegate, practically, was pro. But here arose a new difficulty for there were three factions, each one with a different leader and destination. James M. Whitfield headed one party which was all for Central America; Theodore Holly thought Haiti the most likely land of refuge for black pioneers; and Dr. Delaney saw no finer prospect for future colonists than the Valley of the Niger in Africa.

It was during this period in the midst of the colonization fever that Dr. Delaney moved to Chatham, Canada. Two later conventions were held, one in 1854 in Cleveland, the other in 1856 in Chatham. And from the point of view of the student of Negro history, remembering the limited resources of practically all the colored people of that day, astounding results happened. For every one of these apostles of colonization went to his chosen destination —Holly to Haiti, Whitfield to Central America and Delaney to Africa! The expedition for the Niger Valley left in 1859. The party was composed of “scientific men of color” whose business it was to explore certain regions of Africa and to report on the most suitable place for a settlement. It is amazing, if not disheartening, in these times, when to the best of my knowledge not one colored American is the possessor of a seaworthy vessel, to learn that in “early May 1859 there sailed from New York in the Bark Mendi owned by three colored African merchants the first colored explorers from the United States known as the Niger Valley Exploring Party”.

The phrase “colored African merchants” is a trifle ambiguous but it leaves little doubt as to the original nationality of the owners.

The head of the expedition was of course Dr. Delaney. For one year he led his little group through the domains dotting the West Coast of Africa, taking many notes and concluding treaties, we are told, with eight kings and chieftains. His notes he embodied in a pamphlet rather lengthily inscribed after the pompous manner of the time:

“The Official Report to the Niger Valley Exploring Party by M.R. Delaney, Chief Commissioner to Africa, New York, 1861.” It is full however of many wise and valuable observations on the African climate, native customs, proper clothing and the prospects for colonists. The African rulers seem to have received the expedition with favor and interest. Evidently they were as glad to have the Afro-Americans enter their domain as the latter were to come. Indeed as events turned out the Africans were more eager. And their reasons for extending the invitations were based on-sound economic reasons indicating the possession of a fine statecraft and the exercise thereof.

The following treaty concluded by the Niger Valley Commissioners with the native king of Abbeokuta, Tybore, is typical:

“This treaty made between his Majesty Okukenu, Alake; Somoyi, Ibashorun; Sokenu, Ogubonna and Atambala, chiefs and Balaguns of Abbeokuta, on the first part; and Martin Robinson Delaney and Robert Campbell of the Niger Valley Exploring Party, Commissioners from the African Race of the United States and the Canadas in America, on the second part, covenants:

“Article I. That the Kings and chiefs on their part agree to grant and assign unto the said commissioners on behalf of the African race in America the right and privilege of settling in common with the Egba people on any part of the territory belonging to Abbeokuta not otherwise occupied.

“Article II. That all matters requiring legal investigation among the settlers be left to themselves to be disposed of according to their own custom.

“Article III. That the commissioners, on their part, also agree that the settlers shall bring with them as an equivalent for the privileges above accorded, Intelligence, Education, a Knowledge of the Arts and Sciences, Agriculture and other Mechanical and Industrial Occupations, which they shall put into immediate operation, by improving the lands and in other useful vocations.

“Article IV. That the laws of the Egbe people shall be strictly respected by the settlers; and in all matters in which both parties are concerned. an equal number of commissioners, mutually agreed upon, shall be appointed, who shall have power to settle such matters.

“As a pledge of our faith and the sincerity of our hearts, we each if us hereunto affix our hand and seal this Twenty-seventh day of December, Anno Domini, One Thousand Eight Hundred and Fifty-nine.

“His mark + Okukenu, Alake His mark + Somoyi, Ibashorum His mark + Sokenu, Balagun His mark + Ogubonna, Balagun His mark + Atambala, Balagun His mark + Oguseye, Anaba His mark + Ngtaba, Balagun His mark + Ogudemu, Ageoko M. R. Delaney Robert Campbell Witness—Samuel Crowther, Junior. Attest—Samuel Crowther, Senior.”

As it happened nothing came of the expedition. The rank and file of colored people either through timorousness or through the possession of that hard common sense which one so surprisingly finds among Latin and other warm-blooded people had no intention of leaving a land in which they had purchased heritage by wage of tears and labor and blood. Delaney, of course, gained immense prestige. He stopped on his return voyage in London, where he was received with great acclaim and made a member of the famous International Statistical Congress of July, 1860. His presence, it may be said in passing, proved most irritating to the American delegates there assembled, many of whom withdrew, including Judge Longstreet of Georgia. Quite a correspondence sprang up between the aggrieved magistrate and the heads of the convention in which it is significant to remark that even in that calloused age when slavery was flourishing at its height there was .a feeling of almost pitiable shame on the part of white Americans when confronted with a presentation of their wrongs toward their black fellowmen.

The Niger Valley Exploring Expedition and its leader Dr. Delaney came back in troublous times. The country was on the brink of Civil War and shortly plunged into combat. The learned and traveled physician had been engaged in lecturing on the flora and fauna and other attributes of Africa but as soon as war loomed on the horizon he had but one thought and that was to enter the fray. To this end he moved from Chatham back to Detroit and later to Chicago. Such determination as his made success inevitable. He was appointed Acting Assistant Agent for recruiting and Acting Examining Surgeon for the post of Chicago. Later he became Commissioner for Rhode Island, New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio. During this time he was advocating everywhere the advisability of heading black troops with black officers. By dint of great effort he reached the presence of Mr. Lincoln, who finding great good sense in his projects commended him to the kindly offices of the Secretary of War. In 1865 on February 8 he was commissioned Major, the first of his race in America thus to be honored.

His post-war even as his pre-war years were full of activities, now largely political. For three years he labored ardently in the Freedmen’s Bureau; Charleston, S.C., for several years knew his services as Inspector and he held the position of trial justice in the same city for an additional four years. He seems to have been capable of fulfilling any duties assigned him. And all this time amazing to relate he kept up the practice of medicine in which up to a ripe old age he never lost interest.

Finally the hand of time set its seal heavily upon even those vigorous shoulders. In the last one of his seventy-three years, a mercantile house in Boston engaged his services as agent for a firm in Central America but before he could act in his new position he was taken ill in December and died rather suddenly one January day in 1885.

But he had lived such a useful, such a complete and satisfying life that though he was mourned by many not ever he himself could have begrudged his withdrawal from it. To few men is the opportunity given to realize themselves completely. What must not have been his supreme joy to know that he, born in an age when color was a misdemeanor to be expiated with life servitude, attained to honors. such as many a man born under a more favorable star failed to grasp? Of course there were in his career moments of despair, even of failure, but in the main his dreams came true. He lived to see himself become a man among men and millions of his fellows elevated from the status of chattels to manhood and citizenship.

Take him all in all and he was as fine an example of self-reliance and courage as any race might hope for. Dr. Delaney believed that power came from within; he believed it the duty of the American Negro deliberately to plan his future and not leave it to the whims of fate. Wisdom with understanding expressed the sum total of his admonitions and doubtless he would have added: “Embellish that understanding with pride; commit no actions that can shake it.”

In his “Condition, Elevation, Emigration and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States Politically Considered”, he leaves among other valuable bits of wisdom this precious advice:

“Let our young men and young women prepare themselves for usefulness and business; that the men may enter into merchandise, trading and other things of importance; the young women may become teachers of various kinds and otherwise fill places of usefulness. Parents must turn their attention more to the education of their children…Consult the children’s propensities and direct their education according to their inclinations. It may be that there is too great a desire on the part of parents to give their children a professional education, before the body of the people are ready for it. A people must be a business people and have more to depend upon than mere help in people’s houses and hotels, before they are either able to support or capable of appreciating the services of professional men among them. This has been one of our great mistakes— we have gone in advance of ourselves. We have commenced at the superstructure of the building, instead of the foundation.” These are the words of a sound business man and a prophet and we are still in a position to reap an advantage from their observance. But the main lesson bequeathed by his life for his countrymen of a later date was his unshakable pride, the bulwark of his existence, the mainspring of his actions. His blood and his blackness were the insignia of his rank and no gallant of the bravest days of France believed more truly than he that rank imposes obligation,—noblesse oblige.

The Crisis A Record of the Darker Races was founded by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1910 as the magazine of the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. By the end of the decade circulation had reached 100,000. The Crisis’s hosted writers such as William Stanley Braithwaite, Charles Chesnutt, Countee Cullen, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Angelina W. Grimke, Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Jean Toomer, and Walter White.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_crisis_1926-11_33_1/sim_crisis_1926-11_33_1.pdf