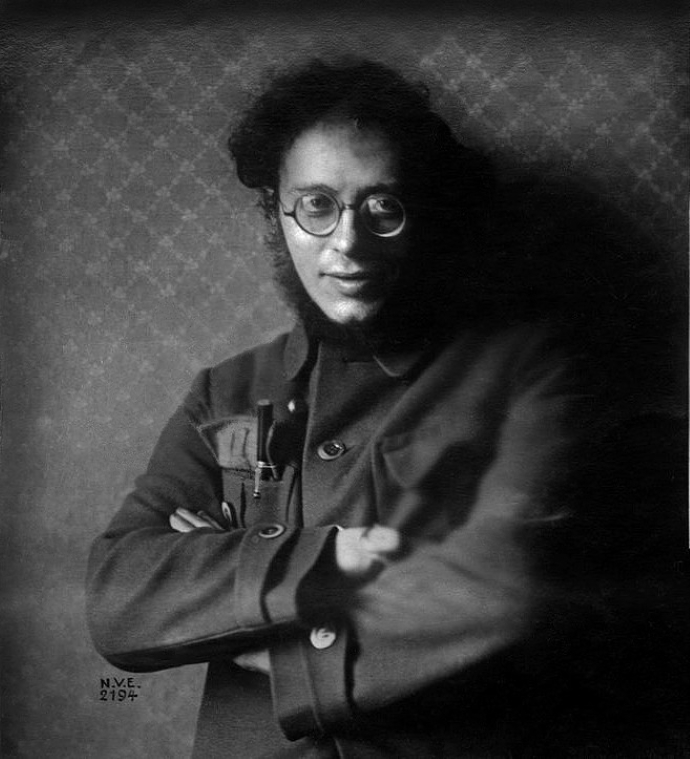

Transcribed here for the first time, Radek’s 1932 portrait.

‘The Life of Adolf Hitler: Career of a Petty Bourgeois’ by Karl Radek from Workers Age. Vol. 1 Nos. 8 & 9. March 19 & 26, 1932.

In a little town on the Austro- Bavarian border there lived a petty customs official. He was a former peasant who had reached the position of an insignificant official thru long and bitter struggle. Even tho his life was not showy or luxurious, it was nevertheless quiet and “permanent.” It is true he had to count every penny and save on everything but he knew that he would have something to eat on the morrow and that a tiny pension was waiting for him in his old age.

This pension was the highest ideal of Adolph Hitler’s father; his imagination could picture nothing more lofty. His dream was to make an official out of his son. But the young fellow dreamed of a freer, broader life of an artist whose talent could raise him out of the stupid existence of the petty bourgeois and working man. Father and son had many a quarrel. But both father and mother soon died and the young Hitler, a petty bourgeois, dreaming of a great career as an artist but finding his road in that direction barred, had to earn his living as an unskilled house-painter!

He went to Vienna, his head full of dreams and antiquated bourgeois ideology. He had read a number of nationalist books of German history. Germany–the young hero, Siegfried, surrounded by enemies. France–the black Hagen, waiting for a chance to sink his dagger into the back of the young knight. What was threatening the hero now? In Austria the Germans had to fight against all sorts of “Slavic cliques.” Then there were the Jews; they “corrupted the spirit of the German people”, as he had already learned from the leader of the Viennese anti-Semites, Dr. Lueger. The Slavs and the Jews were being helped by the Social-democrats, who were propagating the class-struggle among the masses of the people.

With the masses of the people Adolph Hitler now came into immediate contact. The Viennese building trades workers were organized into a trade union and they called upon the petty bourgeois to join the union. here began Hitler’s first conflict with the workers. He treated their demand with contempt. He didn’t want to be a worker. For him the building upon which he was working was a prison from which he was trying to escape as quickly as possible. He–the “free artist” of the future–would have nothing to do with labor solidarity. He had no contact with his fellow-workers and drew away when, in the lunch hour, they would get together, read the Social-democratic papers and discuss what they read. He would gulp down his meager meal and dream of another world, of finer surroundings. He was overjoyed when he was able to escape from the building and “go inside” into the office as a sketcher. Into an office with men wearing white collars-men after his own heart, men who hated Jews, Czechs and workers!

The War and After

Before the war Hitler left Austria and moved to Bavaria. He lived the life of the down-at-the-heels bohemia, consisting of part-time workers, sketchers, painters, with the ambition of becoming artists. The World War burst out and Hitler joined the German Army as volunteer. One historian believes that this step is not unconnected with the fact that Hitler had not fulfilled his military service requirements in Austria and adopted enlistment as a way of avoiding “unpleasantness.” However that may be, it is a fact that Hitler went to war, his head full of the slogans of Germany’s innocence and the glorious future to come. Without doubt Hitler saw in the war an opportunity of rising out of his own hopeless position. Perhaps he would become an officer and so open a new page in life! But he never reached a commission. Wounded he returned home and watched all his hopes and dreams collapse in the general catastrophe. Germany defeated and all the sufferings of war were in vain!

What Hitler did immediately after the war is uncertain. He himself says nothing concrete. But one thing is clear: he struggled for his bread, he made no attempt to play any sort of political role, and, during the short existence of the Bavarian Soviet power, he remained in Munich not letting himself be heard from in any way. It was only after the fall of the Soviet government that he joined the Bavarian White formations-whether as spy or as an agitator, is not clear. He was sent to workers meetings and had to submit detailed reports to his superiors. Here Hitler had, for the first time, the opportunity of studying at close hand the mysteries of political propaganda and political technique. He also came into contact with the nationalist organizations that were just arising and were carrying on agitation among the workers and the “small people.” These organizations were unpopular, even with the most backward workers. They bore too obviously the brand of reaction; they did not understand how to speak to the workers and to the excited petty bourgeois. In these organizations, Hitler learned of the responsibility of the Entente for the ruin of the middle classes, here he learned also how an emancipated Germany would free the people of the war debts. Here he learned that the “Jewish money-power” must be destroyed so as to open the way for the deserving. They were almost the same ideas as Hitler had heard years before in the meetings of the Austrian anti-Semites. Only the combination of nationalism and anti-Semitism was new. It was in these surroundings that Hitler collected his armory of ideas. The fact that these ideas became the point of departure of his movement is to be explained by the condition of Germany in the days after 1920, by the rapid economic collapse that set in in Germany in those days.

Inflation and Big Capital

Germany was forced to pay reparations. German capital paid them primarily with the assistance of the printing press. New paper money was continually being produced and thrown on the market. The petty bourgeoisie in the foreign countries, who believed the mark would certainly rise again, bought the paper marks and hoped to make fortunes. The inflation was stimulated by the big capitalists who used the opportunity to buy up factories and propert.es. houses and newspapers. For this they received paper money from the Reichsbank and paid it back when i had entirely lost its value.

Stinnes was one of the initiators of this policy and he well understood how to disguise it in patriotic phrases: “The collapse of the mark will make the foreigners suffer.”

The costs of this policy were borne by the workers and the middle classes. Wages kept rising but you couldn’t buy anything for the money in which you were paid. The urban petty-bourgeoisie went to extremes trying to keep their heads above water. It was overwhelmed with fear of the future!

The kings of coal and iron, who got most out of the great inflation, succeeded splendidly in distracting attention from themselves. They had not participated in the government. They had left that to the Social-democrats, to the Center, to the Democrats. Of course, Stinnes had issued the commands but the responsibility for them had to be borne by Scheidemann and Erzberger, whom Stinnes was denouncing in his papers as responsible for everything evil and as traitors to Germany. The nationalist papers, financed by him and Hugenberg, told the petty bourgeois popular masses that the inflation was a consequence of Marxism because Marxism wanted the destruction of the middle class, and because Marxism aimed at the surrender of Germany to its enemies.

The leaders of monopoly-capital were, however, not content with merely newspapers. They began to finance nationalistic secret organizations in order to use them as a means of pressure against the democratic government, if the latter, in fear of the voters, showed any restiveness. Hitler’s agitation registered great success among the petty bourgeoisie. He succeeded in drawing great masses of the petty bourgeois strata to his meetings and, to win tens of thousands of them to his organization. The young officers from the secret organizations came to his aid and there was organized the first of the Sturmabteilungen (Storm Divisions) whose original task it was to protect the Hitler meetings against the antagonistic workers.

As is well known this period of development of the national-socialist movement ended in the catastrophic collapse of November 9, 1923. Let us examine this collapse which is so characteristic of the mechanics and aims of the Hitler movement.

The Bavarian Adventure

How was Hitler able to succeed to sink such deep roots precisely in Bavaria? The simple fact that he, the Austrian, understood the South German environment exceptionally well, is insufficient. Rather must we study the whole complex of social-political relations in Bavaria and the role that Bavaria played in the program of French imperialism.

French imperialism, not content with Versailles, strove for the partition of Germany. Influential French military men and diplomats worked out a plan for the creation of a South German state under the rule of the Wittelsbacher. This state was to unite Catholic German Austria with Catholic Bavaria. France even maintained a legation in Munich. Cardinal Faulhaber and Prince Rupprecht were in eager negotiations with the representatives of France. These intrigues were conducted under the banner: “Protect the Bavarian middle class against the ruin brought about by Jewish-Protestant-Bolshevist Berlin!” Bavarian separatism saw point of support in the Hitler movement altho Hitler was mouthing phrases against France. For the main thing was the agitation against Berlin and that was enough to make them allies. Thru unification with the Ludendorff group, who had a great reputation in military and petty bourgeois circles, the Hitler movement achieved a greater significance. and the nationalist officers flattered themselves that they were not instruments in the hands of the Wittelsbacher, the Catholic Church and monopoly-capital, but that they were going to make Bavaria into a jumping-off point for the winning of all Germany. A section of heavy industry stood behind Hitler and Ludendorff. But in the decisive moment, after the Ruhr invasion and inflation had been ended, at the moment that Hitler and Ludendorff, without waiting for a final understanding with General von Seeckt, attempted to seize the state power in Bavaria, at that moment it suddenly appeared that the petty bourgeois Hitler and the nationalist-romanticist Ludendorff had been deserted both by heavy industry and by the Bavarian separatists.

For, as heavy industry became convinced of the fact that the possibilities of inflation had been exhausted and that the further pauperization of the middle classes and of the working class would involve a serious and immediate danger of revolution, it decided to reach an agreement with France. For this it was not necessary to overthrow Ebert, who had already deprived himself of power in favor of General von Secckt and who had unleashed a war against the left Saxon government. And so Stinnes dumped his “financial dictator,” Minoux, his contact with Ludendorff— and he dumped Hitler. It was decided in Bavarian clerical circles that after an agreement had been reached with France there was no longer any occasion for the separation of Bavaria. And Hitler, who only yesterday had succeeded in surprising the Premier, Kahr, suddenly found himself persecuted by the Bavarian police. The savior of the nation had to flee from Munich and even to submit to arrest!

The New Hitler Program

As Hitler and his followers recovered from the defeat, two things became clear to them. First, it became obvious that a much more compact and elastic independent organization of their own had to be created if they expected to be taken seriously by big industry. Secondly, it was no less clear that no adventures against the captains of industry were to be thought of. Of course there was a certain contradiction between these two conclusions but we will soon see how this contradiction was resolved.

In order to create an organization of their own, in order to win the broad masses of the petty bourgeoisie and to penetrate into the workers quarters at the same time, there was required social demagogy of such unlimited scope as to cover the most diverse sections of the population. In its twenty-five theses, the Hitler program contains the most varied promises to the most different strata of the population.

First of all it appeals to the nationalistic instincts of the petty bourgeois. Only a German of “pure race” can be a citizen of Germany. The Versailles treaty must be torn up and Germany must get its colonies back. But all these things had been long demanded by the nationalists as a whole and yet they had not made an appreciable impression upon the petty bourgeoisie, not to speak of the working class. And so Hitler adorned his program with social ornaments. The state must provide the conditions for “the economic advance of all citizens.” “Should it be impossible to feed the entire population of the Reich, then all inhabitants of non-German origin must be expelled from Germany.” But how should the German economy be constructed?

“The abolition of unearned income! The destruction of usury-slavery!” “We demand the nationalization of all hitherto already socialized concerns (trusts).”

“We demand profit-sharing in big ‘concerns.”

“We demand the creation of a healthy middle class and its maintenance. We demand the communization of the big department stores (and chain-stores, markets) and their leasing out at low prices to small tradesmen, the greatest consideration for all small tradesmen to be given by the state, the provinces and the municipalities.”

Such demands were most energetically propagated in the National-Socialist press. In tens of thousands of meetings agitators waved their program around like a flag. It was made to show that they wanted to protect all poor elements against the exploiters. Up to today the Angriff bears the slogan: “For the oppressed–against the oppressors!”

The Social-democrats tried with the help of bourgeois scholars, to convince the Nazis that within the capitalist system of society interest-taking and usury could not be eliminated, because lending by capitalists could not take place otherwise. They attempted to prove that big concerns, as well as big department stores, could not be rented out in pieces, because that would destroy the whole significance of their economic function. But naturally such arguments could not weaken the attractive power of the Nazi slogans. The department and chain-stores push the small merchant out of existence. What does the small merchant care about economic reason. Down with the department and chain-store! And what artisan in debt is not in full agreement with the abolition of debts? Quite naturally this slogan had a big effect with the peasantry, stifling under the load of debts. What was going to happen with capitalist credit, they declare, let the capitalists–and the Social-democrats–worry! The demagogic program of the Nazis won for them the broad masses of the ruined petty bourgeoisie, which remained absolutely pauperized with the end of inflation and the beginnings of stabilization.

The Consolidation of the Nazi Organization

Having taken to heart the experiences of 1932, Hitler now worked not only for the extension of his influence but also for the consolidation of his organization. After the defeat of 1923 his party counted no more. than a few thousand members. In July 1928 it had already risen to 80,000. Now they have at least 800,000 members, among whom are the 300,000 members of the S.A. and the S.S. (armed divisions. Editor.) Perhaps these figures are exaggerated but even the Social-democrats, the strongest mass party in the Reich, have to admit that in many places they fall behind the Nazis.

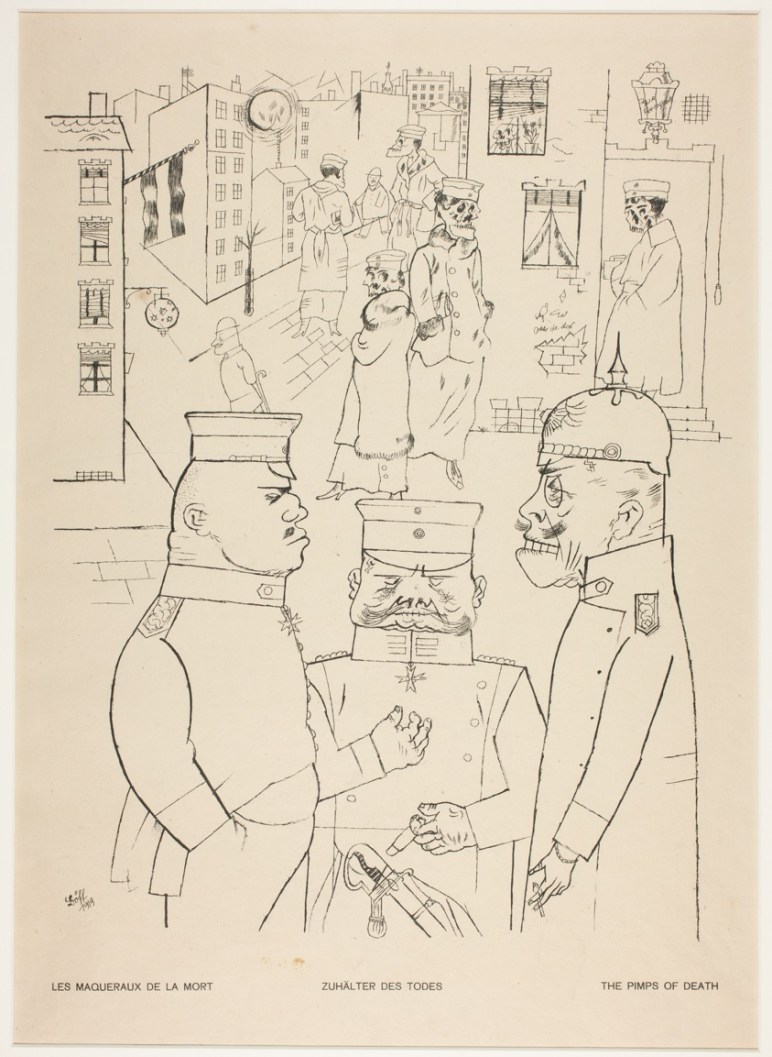

The National-Socialist organization is essentially different from that of the usual type of bourgeois party. The ordinary bourgeois parties have no stable mass organizations. They have only an organization staff and a big press. When elections approach, the apparatus is set in motion and so they exercise their influence upon the popular masses. Aside from parliamentary elections they don’t need any organization. The bourgeois parties create the legend of the free expression of the will of the voter in the elections, in the act of expressing confidence in one or another party. The National-Socialist party fights for a dictatorship, open and undisguised. Of course they don’t reject any of the instruments of power of the capitalist state. But since their dictatorship is to be the terrorist dictatorship of big capital and the chief task of this dictatorship is to be the destruction of the revolutionary labor movement, it is clear that a military and not a democratic organization is requisite. Therefore the nucleus of the Nazi organization is formed by the Sturmabteilungen, military bodies trained in the art of civil war and ready at any time for armed attack. The petty bourgeoisie, following the Nazis, love to rattle the saber over a mug of beer but for real war they have no very great liking. Therefore the S.A.’s are formed not out of merchants or artisans or similar elements but out of slum-proletarians, out of unemployed workers corrupted by a small wage, and out of students who play leaders and imagine that the S.A.’s are the future army not only of the civil war but also of the war against France.

The Power of the Nazi Slogans

People who have had the opportunity of being present at Hitler meetings ask themselves in astonishment: “What is the source of his influence? Why do the petty bourgeois hail him. with such enthusiasm? He cannot boast of one clear idea and certainly of no concrete thought-out program. He is nothing but a confused and superficial enthusiast.” A well known. writer notes cynically: “He possesses the courage to be banal.” But whoever puts the question in this manner drops the petty bourgeois masses themselves out of consideration. For the petty bourgeoisie there are no concrete, thought-out measures that can help them immediately. With tooth and nail, they cling desperately to everything that perhaps can prevent them from being driven down to a lower social stratum, to the proletariat, altho precisely this is the only real way out for them. In such a situation there is nothing for the petty bourgeoisie to do except to attempt to apply the senseless recipes of the quack Hitler and to give car to his phrases. Never has the petty bourgeoisie had an independent political idea, never has it independently solved a political question. Therefore it looks eagerly to the idea of a savior-hero, who can do for them what they cannot do for themselves. That the promises of the Nazis are unreal only corresponds to the fact that a petty bourgeois domain in an imperialist world no longer possess any possibilities for real existence.

When Hitler, surrounded by the banners of the Storm-Battalions, appears in the hall and mounts the tribune amid the sound of ten military bands, the entire petty bourgeois mass, electrified, arises and greets its savior, the prophet of the Third Reich, in which a commodity-economy will, of course, persist, but no capitalism, no exploitation! When Hitler proclaims the holy war for the “honor of Germany,” the war for the emancipation of Germany not only from the shackles of the Versailles treaty but also from the “yoke of the Roman law,” then the petty bourgeois is happy, altho, of course, he doesn’t know what the Roman law is all about; then he is overjoyed at the prospect of the reestablishment of the never-existent German law, of which he knows even less-because he confidently assumes that the change will mean the abolition of debts. When Hitler lets loose against the “lyrical French literature” and promises the return of “lofty Nordic art,” the petty bourgeois feels his soul rise within him, altho, of course, he has never heard of the Eddas or of the Icelandic sagas, for he fancies himself a Viking of the spirit, triumphing over the cursed “French diseases.” When, finally, Hitler announces the defeat of Jewish philosophy, the small tradesman understands by it not so much the expulsion of Einstein from the German higher schools as the destruction of the Tietz and Karstadt department stores.

And Hitler Himself?

At the same time, however, that in the electrified atmosphere of the mass meetings the soul of the petty bourgeois arises above the fumes of tobacco and beer, there take place, behind the scenes, the most friendly negotiations between Hitler and the leaders of the German banks and the heads of the metal trust. Hitler long ago ceased being an “enraged petty bourgeois” operated as an unconscious marionette in the interests of the forces of reaction. Hitler long ago became the cunning, conscious paid agent of monopoly capital. With the help of the money of heavy industry he created his party and in this process he overcame his petty bourgeois illusions as to the aims of the party. He knows well enough that the National-Socialist party must help monopoly capital deprive the working class of its rights so that the unlimited exploitation of the working masses can become the fruitful source of the rebirth of German capitalism. He appreciates his own role perfectly well. But he also understands, as do all praetorians, how to keep his price high and to keep it always getting higher.

Workers Age was the continuation of Revolutionary Age, begun in 1929 and published in New York City by the Communist Party U.S.A. Majority Group, lead by Jay Lovestone and Ben Gitlow and aligned with Bukharin in the Soviet Union and the International Communist (Right) Opposition in the Communist International. Workers Age was a weekly published between 1932 and 1941. Writers and or editors for Workers Age included Lovestone, Gitlow, Will Herberg, Lyman Fraser, Geogre F. Miles, Bertram D. Wolfe, Charles S. Zimmerman, Lewis Corey (Louis Fraina), Albert Bell, William Kruse, Jack Rubenstein, Harry Winitsky, Jack MacDonald, Bert Miller, and Ben Davidson. During the run of Workers Age, the ‘Lovestonites’ name changed from Communist Party (Majority Group) (November 1929-September 1932) to the Communist Party of the USA (Opposition) (September 1932-May 1937) to the Independent Communist Labor League (May 1937-July 1938) to the Independent Labor League of America (July 1938-January 1941), and often referred to simply as ‘CPO’ (Communist Party Opposition). While those interested in the history of Lovestone and the ‘Right Opposition’ will find the paper essential, students of the labor movement of the 1930s will find a wealth of information in its pages as well. Though small in size, the CPO plaid a leading role in a number of important unions, particularly in industry dominated by Jewish and Yiddish-speaking labor, particularly with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Local 22, the International Fur & Leather Workers Union, the Doll and Toy Workers Union, and the United Shoe and Leather Workers Union, as well as having influence in the New York Teachers, United Autoworkers, and others.

For a PDF of the full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-age/1932/v1n08-mar-19-1932-WA.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-age/1932/v1n09-mar-26-1932-WA.pdf