In the four years between the 5th Congress of the Communist International in 1924 and its 6th in 1928, the organization had changed enormously. The period of relative capitalist stability saw factionalism, ‘Bolshevization,’ and expulsions in the older parties and many new parties, particularly from the colonial and neo-colonial world joining the International. One of those was the Communist Party of Korea founded by 15 participants at an April, 1925 meeting in Seoul. Here is the Korean Party’s report to the 6th Congress on conditions and activities.

‘Report of the Communist Party of Korea’ from The Communist International Between the Fifth and the Sixth Congresses, 1924-28. Published by the Communist International, 1928.

THE ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL SITUATION.

THE main characteristics that marked the economic situation during the period dealt with in the report have been: increased subjection of the entire economic life of the country, both in town and country, to Japanese finance capital; attempts at industrial development, the construction of railways and electrification under the complete control of Japanese trusts and enterprises; unlimited monopoly of credit by two Japanese banks, which are under the immediate control of the government; a further concentration of the best land in the hands of land grabbing syndicates and the utilisation by the Japanese of the irrigation systems, which they have monopolised, for the complete enslavement of peasant economy and the maintenance of feudal conditions in the village. This growing power of colonising monopoly is accompanied by a return to the fierce terror that prevailed at the time of the conquest of the country; the miserable concessions that were made after the suppression of the mass movement of 1g19, are now practically con-existent. Mass organisations are being crushed, the meetings of those organisations that are still legal are broken up; mass arrests take place accompanied by torture; court trials are staged by provocateurs, with a view to future unbridled terror. The number of military and police in the country is on the increase.

The development of industry may be judged from the following brief data:

DEVELOPMENT OF INDUSTRY FROM 1911 TO 1924.

The number of factories in 1924 was fifteen times that of 1911, capital twelve times, and the number of workers five times.

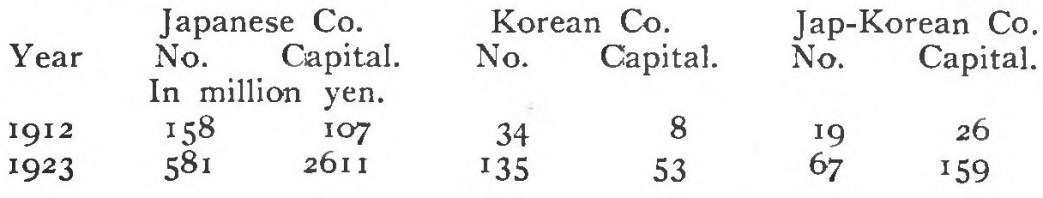

The growth of share companies will convey an idea of the dominating role of Japanese capital in the most important branches of industry.

Since 1926 the big Japanese enterprises, despite the financial crisis in the capital, are launching large scale building plans. Thus, in the railway section the plan is to build 65 new lines in the course of twelve years (1926—1938), which will mean an enormous increase in the present railway system. The electrification plan to be realised by 1932, comprises a supply of electric energy 35 more times than the present supply.

The policy of the rationalisation of agriculture, which is directed towards raising the production of rice and increasing the export of same, is aided by the concentration of all systems of irrigation and other improvements in the hands of a few dozen companies and artels, with a capital of more than 100 million yen; a situation which facilitates the further enslavement of the peasantry.

The enormous concentration of power in the hands of the conquerors results in the development of industry by means of trusts and companies, which crush and submerge small scale production.

The development of capital under such conditions, causes wholesale plunder in the village, where the small peasantry with little or no land, deteriorate into a state of colonial slavery. The ruin of the main body of the peasantry, who constitute 82 per cent. of the population, is bringing about the impoverishment and the ruin of the entire Korean people, whilst Japanese capital investments grow from day to day, with a view to increasing their super-profits in Korea.

Since coming under Japanese control, the policy in Korea has been to break up the Korean village and ruin the weakest inhabitants, who are in a state of slavish dependence on a technically backward agriculture.

The number of tenants and big landowners increases ; the middle group of semi-tenants and small proprietors decreases: the tenants and semi-tenants constitute 77 per cent. of the peasantry and holds 17 per cent. of the entire land. The rents are as much as 60 per cent. of the harvest. The parceling out of land, because of the excessive rents, the difficulties of the situation, the complete arbitrariness of the landlords, etc., all facilitate the speedy penetration of the Japanese plunderers into the village.

The Eastern Colonisation Society in the course of nine years, doubled the acreage of land in its possession. However, to get a real idea of the extent of the seizure of land by this Society it should be pointed out that the quantity of land under its control is a million zioby; there can be no doubt that the greater part of this land will remain in the hands of the Japanese conquerors, owing to the miserable economic position of the peasantry.

In addition to the Eastern Colonising Society there are dozens of other land grabbing Japanese enterprises, which drive the Korean peasant from the land. The peasant driven off the land cannot find work in the towns and is forced either to starve or emigrate. In 1920 about 100,000 emigrated to Japan, Manchuria and the U.S.S.R. In 1926 the number of peasants driven from the land was about 120,000. The general impoverishment and desperation, which is expressed in the increase of the number of suicides and deaths from starvation, is a proof of the pauperisation of Korea, which even official statistics cannot possibly conceal.

NATION-REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENT.

During the period under review, the national-revolutionary struggle was marked by an endeavour to consolidate the forces of the scattered and dismembered national-revolutionary movement. An attempt was made to overcome the group struggles, which did not always express the real class differences, “struggles due to the comparative weakness of the industrial proletariat in the country and the tactic of fierce terror and conscious provocation employed by Japanese imperialism.” But so far, the successes attained in the work of consolidating the forces of the movement have been small.

The insignificant role which the Japanese allot to the Korean bourgeoisie in the industry of the country is not sufficient to bring it over to the side of the government. On the other hand the nascent peasant movement provokes the bourgeoisie all the more since it participates in the ownership of the land and growth of the village. The first independent movement of the proletariat, was the main cause of making the bourgeoisie in Korea go over to the side of the oppressors. At the same time Japanese imperialism is dragging a section of the intelligentsia into the bureaucratic machine, and thus making them the hired agents of its actions in connection with the national movement.

As a result of this situation in 1924, the bourgeoisie organised a reformist party with a view to carrying on negotiations with Tokyo, for the autonomy of Korea within the boundaries of Japanese imperialism ; some former leaders of the nationalist movement participated. This party decided not to act openly and concealed its plot with Japan; it published anonymous articles calling on the nationalist movement to break with “the criminal revolutionary tradition of the past.” However, this reformist-bourgeois party declared its dissolution when its activities were exposed by the revolutionary organisations. But of course, the bourgeoisie continues its attempts to negotiate with Japanese imperialism, and is using all its forces for the disorganisation of the national-revolutionary movement.

The first really big attempt to unite the activity of the mass nationalist organisations was made in 1925. About 1000 attended the unity conference. The Japanese police did not stop at open repression, but took measures to incite the various groups against one another through the instrumentality of provocateurs. The Congress was broken up and some of its organisers were arrested; then followed mass police arrests throughout the country, domiciliary searches amongst the Communists, who were accused of having organised the Congress. In 1926 another attempt was made, but this time on the basis of a definite programme of action for the unification of the national revolutionary organisation.

The influence of the Chinese revolution and the widespread campaigns on behalf of the starving in Korea, did much to rouse the masses to activity. The June events of 1926, in connection with the funeral of the former Korean emperor, gave an insight into the growth of this activity and the absence of the necessary oganisational leadership. The Communist Party approached the national revolutionary organisations and proposed the creation of a united national-revolutionary front (to include not only workers, but peasantry and artisans; also intellectuals, the petty bourgeoisie and to a certain extent, the middle classes) on the platform of the struggle to drive the Japanese army and police out of Korea, to establish democratic freedom, to satisfy the elementary demands of the workers’ and peasants’ movement, etc. The Communist Party was to do the necessary work of drafting the general programme of action for all the organisations engaged in establishing the national revolutionary front and help temporarily in respect to the organisational independence of each one of them. The question of forming a united national revolutionary party was to be considered as the next stage in the work. In January, 1927, the preparatory work was begun for the organisation of the national revolutionary party. At the end of 1927, this organisation had 100 local groups; the party congress planned to take place in January, 1928, was prohibited by the government.

THE LABOUR MOVEMENT.

In spite of the increase in the number of industrial workers in connection with the growth of industry in recent years, the workers movement is badly organised and scattered. This situation is both the result and the cause of the organisational weakness of the national-revolutionary movement. The Japanese terror, which destroys the most active elements amongst the workers in Korea, prevents by every possible means, the growth of the organisation of the workers.

Trade Union organisation amongst the workers in the basic branches of industry; railway workers, miners, woodworkers, fishermen, etc., is of a poor character, the existing trade unions include also non-proletarian elements, even unemployed intellectuals. The attempts to unite workers and peasants organisations resulted in the formation of the “All-Korean Federation of Workers and Peasants Unions” in 1924, which in 1926 combined 312 organisations (140 workers and 172 peasants). However, the necessity of an independent organisation of Trade Unions raised the question of dividing this federation into two independent sections—workers and peasants; but the congress which was to decide this question was prohibited by the police. Only in 1927, and then only by submitting a written questionnaire to the Federation members, was a decision taken to split up the federation. The Korean Workers’ Federation is the first organisational centre of the Korean Union movement.

Notwithstanding the weakness of the organisation, several strikes took place during the period under review, and some of the strike leaders brought the masses nearer to the Communist movement. The most important strikes include that of the tram workers in Seoul in 1925, the miners’ strike in 1927, the transport workers’ strike, and a number of printers’ strikes. The miners’ strike lasted three months, and received the support of the entire proletariat of Korea; it coincided with a general solidarity strike of the workers in those localities situated near the mines.

The following tasks demand immediate attention in the Korean Trade Union movement; the reorganisation of the existing Trade Unions, the organisation within the basic branches of the workers, especially those engaged in the big factories and mines; sporadic workers’ movements for economic purposes to be linked up with political demands.

THE PEASANTS MOVEMENT

It ha.s become quite apparent that the peasant movement in the village, based on the ruin and enslavement of the peasantry is not equal to coping with the extreme weakness and disorganisation that prevails. The peasant movement has not gone beyond the struggle for the immediate demands of the peasantry, and the overwhelming majority of conflicts are connected with the renewal of the right to lease land, the arbitrary seizure of land from the peasantry by the landowners, reduction of rent, etc. The recent period has been noted for the persistence of the peasants conflicts, and what is of especial importance, the growing contact between the peasants and workers movement, which is shown by the workers’ support of the peasants demands. The number of Left peasants societies has increased, but they are limited to a few tenants, so that the mass of the peasantry continues to be unorganised. There is a weakening in the influence on the masses of old, semi-religious peasant organisations of the type of Chendo-hei, but it is difficult to define in how far this is due to the growth of the influence of the Left peasant organisations, which constitute the most important factor in the development of the revolutionary movement in the Korean village.

COMMUNIST PARTY.

One of the most important attainments of the Korean revolutionary movement during the period under review was the formation of the Communist Party in 1925 (officially recognised as a Section of the Comintern in 1926).

In spite of the mass arrests, provocation, and cruel torture the Party has been able to exist, to gain a certain contact with mass organisations and act as the bearer of the elements of leadership in the national revolutionary movement. The Party has not always been able to take as active a part as the tasks arising in the workers and peasants movement required. One of the reasons which has hampered the Party in its activity is the fractional struggle arising out of the petty bourgeois, individualistic tendencies that continued to exist within the Party. However, the growth of the workers’ movement and the development of an active body of workers together with the heroism shown by certain Communists in the struggle with reaction serve as a proof that the Korean Communist Party will be able to establish its organisation under conditions of extreme terror; that it will enter into a closer alliance with the masses and become the leader of the national revolutionary movement

The Communist International Between the Fifth and the Sixth Congresses, 1924-28. Published by the Communist International, 1928.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/comintern_between_fifth_and_sixth_congress_ao2/comintern_between_fifth_and_sixth_congress_ao2.pdf