An out of work wobbly travels from Seattle to Alaska to dig clams, loses a strike, gets a job in a cannery, a fishery, and finally as a gibber on a saltry (gut herring on a floating salting factory), before giving up and returning home after six months and writing this engaging report.

‘Slavery in Alaska’ by Walter Bacon from Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 3 No. 9. January, 1926.

HAVING wintered in Seattle and hearing that the clam-canneries of Alaska were going to ship men to Alaska to dig clams, I decided I might as well be in Alaska as in Seattle looking for a master. So along in the latter part of February I applied for a job, and after answering many questions I was signed on to dig clams at Cordova for the season of 1925, the wages being ‘three. cents per pound, and a bonus of one-half a cent if I stayed the season. In other words, they bet me one-half a cent on each pound that I dug; conditions were so bad that I couldn’t stay.

On the twenty-sixth of March I received a letter telling me to call on the day following at the office of the company in Seattle for my ticket (which they were advancing) as we were to leave Seattle at 9 a.m. March 29th, on the S.S. “Yukon.”

The trip north was all that a slave could expect —being obliged to pay our own fare, and not being wise to the game nor conditions to be found on the clam beach at Cordova. We went as steerage passengers, and the accommodations were anything but the best. The steerage passengers must furnish their own blankets. The bunks were four high and placed down below the water line, so the ventilation was very poor. The “chow” furnished was mostly stew and boiled liver, badly cooked; the pastry was good, but we received plain cake and no pie. Considering that we only had to pay $37 for our passage and a chance to supply the world with clams, I suppose we shouldn’t complain. The trip was favored with good weather all the way, which is unusual for that time of the year, and the scenery along this trip is fine at any time of the year.

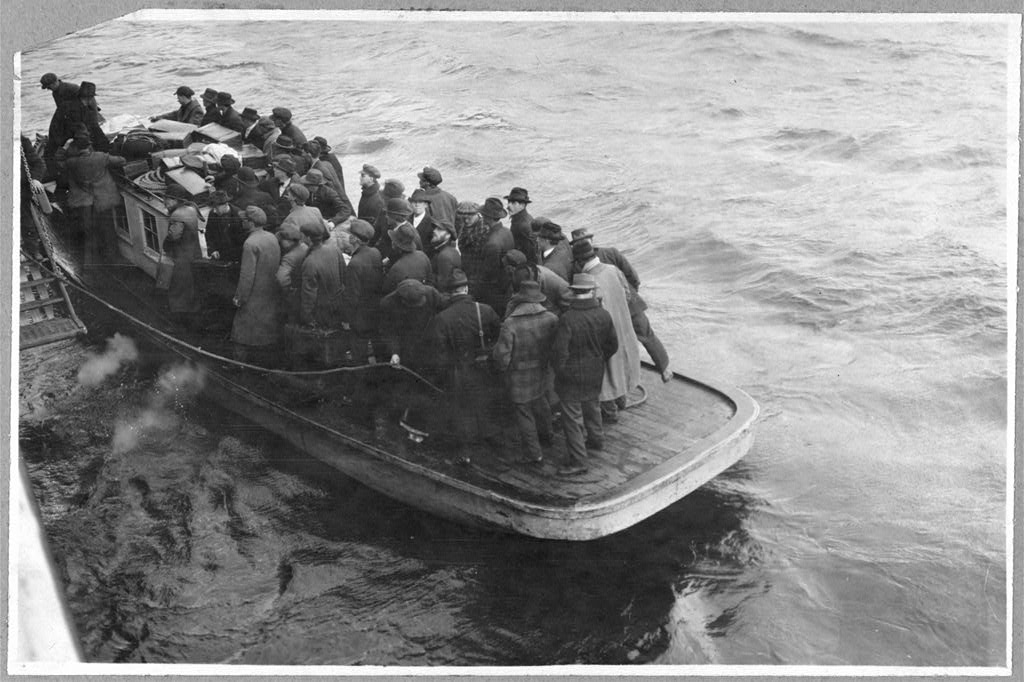

We arrived at Cordova on April 2nd at 2 p.m., and proceeded to inquire for the cannery which had loaned us the privilege to dig clams. After locating the office we were outfitted, and by 6 p.m. we boarded a cannery tender bound for the camping grounds, nine miles away.

Just before casting off, a tax collector came on the deck with a list of our names, which she had secured from the office of the company, and had us give our age, so that they could collect $5 from each of us.

As to the camp and conditions we found there, I will say this: According to our agreement, we were to be furnished a cabin for each two men, the said cabin to be equipped with a stove, dishes, bed, and mattress. When we arrived at this camp we found that there were only about half enough cabins to go around and, being broke, we had to crowd into these small quarters and make the best of it. These cabins had not been occupied for eight months and were exposed to the snow and rain, so that they were water-soaked. The stoves furnished were small sheet-iron camp stoves (the variety with no grates) and our fuel was to be one hundred pounds of coal per week.

After a week or so we were furnished lumber and a tent which we had to put up ourselves. Groceries were advanced us—to be paid for out of the first money earned, along with the fare and any other expenses. At these camps there were no facilities for bathing or washing one’s clothing. Our supplies were brought out to us two days after ordering them.

Our groceries came from the company commissary and though they seemed to have a different price for everybody, they charged everybody enough.

At these clam camps there was no medical attention, not even a first-aid kit furnished. If one had an accident or was sick he just got to town the best way he could.

What the Work Is Like

Clam digging, unlike most work, can only be done at extreme low tide. There is an average of fifteen tides a month which are low enough to dig clams on. The digging time on these tides is about two hours. The clam beds are from one to six miles from camp, each two men are furnished with a skiff (row-boat) and a gas boat for each two skiffs.

During April the weather is still cold and rainy with many days of sleet and snow, and good stiff wind blowing.

After waiting nearly two weeks for a tide that we could work in, the great day came when we could commence producing clams. We arose at 4 o’clock and after an hour of traveling we came to one of the many bars where clams were supposed to abound, but our troubles had just begun as it was still so cold that few clams were showing, and our hands grew so cold and numb that it was next to impossible to hold on to a clam.

I don’t want anyone to draw the conclusion that the conditions in all the camps are the same as in this one, as I learned later that in some they were worse. In one camp they had no power boats and the diggers were obliged to row to the bars, which took several hours of strenuous work.

One camp was on an island which was not much more than a bar and at times at high tide the water covered the island. One fellow worker who was working at this camp told me that one night he awoke and got up to see that everything was all right as the wind was blowing hard, he jumped out of his bunk into ice cold water which came above his knees. His kindling had floated away and so there was nothing to do but go back to bed and wait for the tide to go down. The water at this camp was hauled in by a cannery tender and sometimes this boat was late or did not bring enough water to go around.

Clam digging is somewhat of a trade, ana the majority of us had never dug clams before; the main reason for so many green diggers is because the bars are getting dug out and the companies, in order to get clams enough to run their canneries, must put on more diggers each year. In 1924 there were 200 diggers; in 1925 there were nearly 500.

Alaska has a law which makes it a crime, punishable by fine or imprisonment, or both, for having in one’s possession clams under four inches long. A number of slaves were arrested and fined $25 each. But owing to the fact that they were broke the company paid the fine for them, and I suppose they still owe it.

The Strike

After working eight tides during April, I had dug’ 560 pounds at $0.03 per pound, and I owed the company $80 for fare and groceries. Now I was only one of seventy-five men in this one camp in the same fix. There’ were six camps, so we began to compare notes as it were, and on May the 7th we went on strike for $0.04 flat, and no agreement.

There were men from many walks of life to be found on the clam beach, ranging from a corn doctor from Los Angeles to a logger from Duluth. It is a well known fact that unorganized men do not go on strike unless conditions drive them to it, as a last resort. This strike was no exception in that respect. However, we were confronted with a different situation than the majority of us ever had to deal with.

On May 8th 300 men came into Cordova. Three hundred strikers who had come off the beach to try and improve their conditions were broke to the man. I don’t believe there was $50 in the crowd, and the first thing to do was to find a place to eat and sleep.

The hotels and restaurants gave us credit, but some of us thought it would be better not to go too far in debt, so we established a strike kitchen and secured credit for the strike.

It lasted two weeks and was lost. Most of the men went to work at other work, leaving the company holding the sack.

The Canneries Bad Too

Not only did I find conditions bad on the beach but also in the canneries where these same clams are canned.

Girls are hired to clean clams and get 35 and 40 cents per hundred pounds of cleaned clams. During April these girls made $5 each. At one cannery one of the girls told me that the most made by any of them at that cannery for the two months of May and June, was $18. Even at that they were better off in some ways than the men who had done the digging, as they have free fare up and back, and get their board free.

By the 16th of May I decided not to go back to the beach, so I hired out as engineer on a cannery tender for which I received $135 per month.

Fishing Not Good Sport

I was still to see many bad working. conditions. Salmon fishing is anything but pleasant. The fishing here was done on what is known as the Copper River Flats.

These flats are cut with channels leading from the sloughs at the mouth of the river and even the small fishing boats can only navigate while the tide is in. Stake nets were not allowed on the flats in the season of 1925, so the fishing was all done with drift nets during May and June.

The boats used for gill net fishing are small, with scarcely enough room to accommodate two men, so in some cases one man fishes alone. Two hundred and fifty fathoms of net are used, and the drifting is done at slack tide. The fishermen get 75 cents each for King Salmon and fifteen cents each for Sockeyes. Each fisherman is allowed $45 worth of groceries for his board, and if more are used he must pay for them.

The independent fishermen (those owning their own outfits, and selling to whom they please) get $1.25 to $1.50 each for Kings and 30 cents for Reds. These fishermen leave Cordova the first of May for the flats which are thirty miles away. They are obliged to lie out there on those flats in those small boats in all kinds of weather for two months, and they must work night and day during a run of fish. Their supplies are brought out to them by the cannery tenders which make daily trips. Water and coal are also brought them daily. Most of these men are shipped from Seattle with no guarantee of anything; it all depends on the number of fish. Some years fishermen make good money, while in others they scarcely make anything. The season of 1925 averaged them less than $200 each. This is not much even for two months’ work; but when one considers the time wasted, that they leave Seattle the first part of April and get back there the last of August, it is decidedly small pay.

During July and the first part of August the fish are caught in traps which require less men. A few fishermen take pink salmon with purse seins but the canneries pay only two and a half cents each for these.

Wages paid in the canneries are also low. Most of the labor in the canneries is done by Orientals who get $280 for the season, while the rest of the crew get $80 per month and board. The season at these canneries lasts five months.

Ten-Hour Day—Or More

Ten hours is the length of a workday throughout the fishing industry of Alaska. The cannery help is all shipped up from Seattle where they sign an agreement drawn up to give the company all the advantage over the worker.

In this agreement the worker promises to work for the company in Alaska for the season, for so much a month and board, fare from Seattle and return to be paid by the company if said employe stays the entire season; but if he or she quits or is discharged for any reason, the company shall hold out of his or her pay the fare advanced, and any other expenses caused by said employe.

Worth His Salt

On July 9th, having made the last trip to the flats, we were laid off, and I took passage on the S.S. Alaska for La Touche, to look for a master. I arrived there the 10th, and hired out on a floating saltry as a gibber.

Bad conditions were still the order of the day. Low wages, long hours, no facilities for bathing, no place for clothes, lack of fresh water, and no place of recreation are a few things I found to complain about.

Like the clam and salmon canneries, the herring saltries hire the bulk of their help in Seattle, and their agreements are similar: eight dollars per month and board for the monthly men, with fifty cents per hour for overtime. The gibbers signed up to work for 40 cents per bbl. and were to have a bonus of 20 cents per bbl. if they stayed the season.

Piece-work has had the same effect on the slaves in the herring saltries as in other industries. For a few years gibbers were paid $1 a barrel; only men were hired, and they used good judgment and packed no more than ten barrels a day. But during the war women were hired, and they were anxious to get rich quickly, and packed as high as twenty barrels. The usual cut in wages followed. And now they must pack seventeen barrels to receive as much as they formerly received for ten.

The fishermen are hired in two different ways: first (or the old way) they get $50 a month and board, and seven cents a barrel, this to be based on the amount of fish packed; secondly, (or the new way), they pay the fishing crew $1 per barrel, to be divided among five men. This new way is becoming very popular with the companies, for if there is no fish, the men receive no pay.

After working aboard this saltry for a month, we found out that other floating saltries were paying 75 cents for gibbing, but owing to the bonus system most of the crew were afraid to demand an increase. After nearly another month they did get up courage enough to meekly ask for 75 cents per barrel, but were told that they could work for sixty or be paid off at forty. And as that would mean a loss of about $120 each, they decided to work. As for me, I was hired in Alaska, and at a flat scale, so I called for my walking papers. On September 3 I boarded the S.S. Redondo at Blue Fox Bay (where the Floating Saltry was anchored) and on Sunday, September 6, arrived at Seldovia.

The Whims of Poor Fish

Now I heard that the saltries there would run until the first of the year, so I expected to get work and complete my winter stake, but on arriving there I found that there were no herring running at that time.

I got a room at the only hotel and proceeded to wait for the herring to decide to come, and incidentally I began to spend my winter stake, as it cost me from three to five dollars to live in Seldovia.

To make a long story short, I waited until the first of October for that elusive job to show up. Then I was lucky enough to get signed onto a fourmasted schooner bound for Seattle.

Leaving Seldovia October 4 we battled with tides and head winds for nine days and lost nearly all the sails and dropped anchor at Seldovia; we never got more than thirty miles out, and the wind would drive us back. As I never was a sailor, and had never been to sea, I will not say anything about conditions on this schooner as I suppose they were the same as on all other sailing vessels. On the 16th of October we were paid off and the next boat was due the 6th of November.

Good-bye my winter stake.

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/industrial-pioneer_1926-01_3_9/industrial-pioneer_1926-01_3_9.pdf