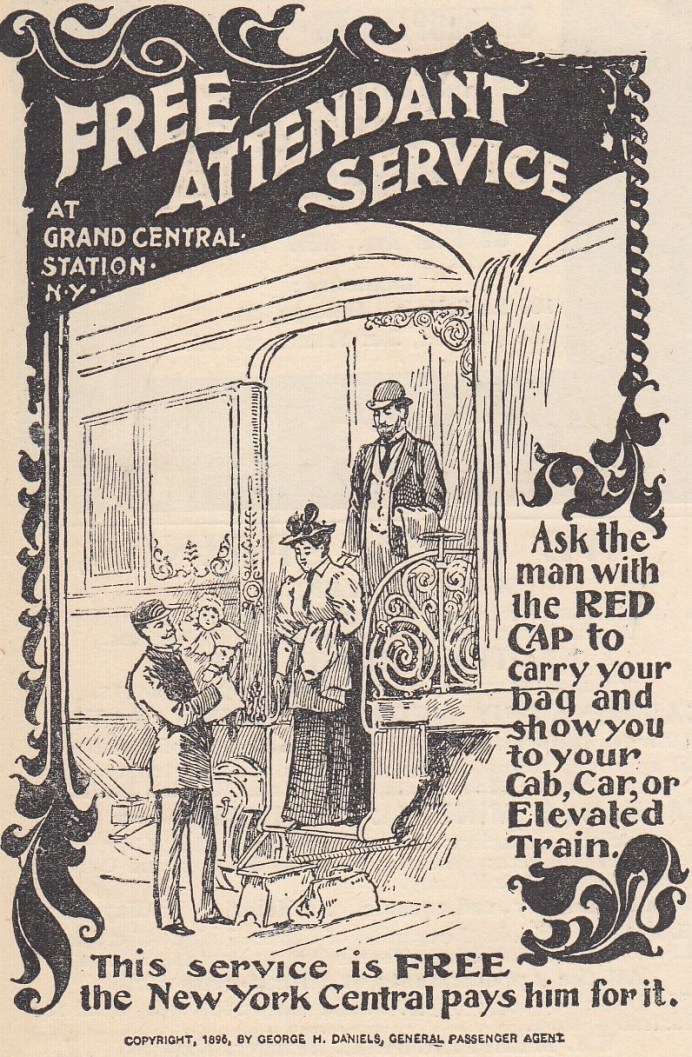

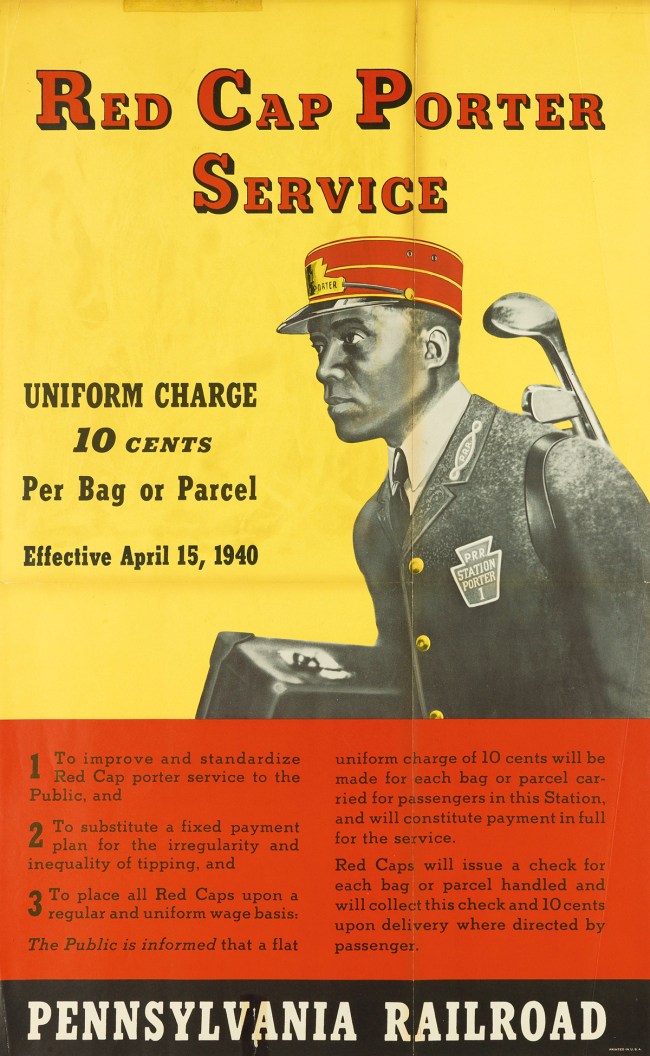

A former Red Cap, exclusively Black railroad station porters whose red hat distinguished them from the blue-capped train porters, describes conditions in the nation’s premiere train station before unionization with A. Philip Randolph’s Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

‘Slaves of Grand Central Terminal’ by Allan S.A. Titley from The Messenger. Vol. 9 No. 10. October, 1927.

Every now and then an article appears in some magazine concerning the Red Caps of Grand Central Terminal, and the general public knowing this body of men merely from a few minutes contact with one or more of its members, accepts what it sees in print as authentic. Never have I seen an article written by one who is or has been a Red Cap, or by anyone really familiar with the work of these men.

The truth is that since the war period the morale of the Red Caps has greatly deteriorated, not through the men themselves, but on account of severe pressure being brought to bear upon them as an unorganized body. During the war men had to be paid, and the Red Cap received a salary of $45 monthly. At that time the force numbered not more than 100 men. Today this same force numbers over 500 men, consisting of 1 Chief, 3 Assistant Chiefs, 13 Captains, 40 regular men who receive $18 monthly, about 100 men receiving $1 monthly and the balance receive no salary at all.

It is generally assumed that the duties of a Red Cap are limited to assisting passengers to and from trains, or acting as guide within the limits of the station, but strictly speaking the responsibilities of these men are much more than the public realizes. The taking of train reports has always been a duty of the Red Cap and is limited to the 40 regular or oldest men. Sometimes one of the $1-a-month men is used if he is detailed on Vanderbilt Avenue. These reports tell if the trains are on time or late and are taken every thirty minutes.

Working overtime with no remuneration, for doing so is one of the impositions placed on a Red Cap. The men are supposed to be on duty 10 hours with one hour for lunch, which leaves nine working hours, except 4 regular night men who receive $36 monthly. These men are supposed to work from 12 midnight to 10 A.M., but on account of business being particularly slow between 10 P.M. and 12 midnight, they have the option of reporting at 10 P.M., which means that they are on duty 12 hours. At any time a notice may be placed on the time clock, “All attendants work until relieved” and if a man fails to obey the order he is severely disciplined. This happens when trains are late, and the men who are not detailed on incoming trains have to remain also.

Owing to the fact that some of the platforms (especially in the lower level) curve at the extreme end, there is a wide space between the rear cars of an incoming train and the platform. This necessitates the placing of boards so that passengers may not slip between the train and the platform. These boards are placed by the oldest men in the station; in other words, men are taken from Vanderbilt Avenue and made to place these boards while the extra men meet the train and wait on passengers.

Twice daily the ticket offices have to be supplied with money from the bank. This also falls on the Red Cap. At 11 A.M. and 1 P.M., 12 men are sent to the Lincoln Bank to bring sacks of silver back to the ticket offices. During a holiday rush, as many as 50 men may be used between both ticket offices. These men are taken from Vanderbilt Avenue, except in cases of emergency a few track men may be used. It is true that they have the protection of a few detectives, but in the event of a hold up there is the possibility of a Red Cap being killed or severely wounded.

It will be clearly seen that the Vanderbilt Avenue men have the responsibility of the work on their shoulders, and these men are given the least consideration of all the Red Caps. The greatest imposition placed upon them is the manner in which they are compelled to return to their detail after waiting on a passenger. In the olden days Vanderbilt Avenue was looked upon as the zenith of a Red Cap’s career owing to the fact that a man had to work himself up to that position through his length of time in the service. This locality was reserved for the oldest men in the station, and a man felt it his duty to take some pride in his work. After waiting on passengers he could return to Vanderbilt Avenue by the shortest possible route and line up behind 30 or 40 men at most. Nowadays, things are entirely different, after waiting on a passenger these men have to walk through the waiting room to 42nd Street and Park Avenue, and remain there until another Vanderbilt Avenue man who has waited on a passenger relieves him. He then walks to 42nd Street, and along Vanderbilt Avenue to 43rd Street, where he lines up behind 70 or 80 men. In other words, this man has walked four blocks where it is only necessary to walk up the stairs. There are times when a Red Cap takes baggage to a car which might be at 47th or 48th Street. This means that when he returns to the train gate which is between 43rd or 44th Street he has walked 3 to 41⁄2 blocks on his return journey. The Vanderbilt Avenue man has to go four more blocks while the extra man can run up the stairs if porters are needed on Vanderbilt Avenue. No plausible reason has ever been given for this outrage, more than that it is necessary to cover 42nd Street. (One would think that with 500 men in the station some means of covering 42nd Street could be worked out without imposing on the oldest men in the station.)

The Extra man has his problem to solve, but of quite a different nature to the regular man. He pays $1 for his numbers (on each side of his cap) and about $30 for his uniform and cap, and then he can hustle. But he has about 400 men to contend with on the tracks and this means, to make a living, he must get jobs that really do not belong to him. He is not expected to do anything else but make what he can. He has the detail of the whole station. In other words, a regular man’s detail is confined to Vanderbilt Avenue, while an extra man’s detail is Grand Central Terminal.

The efforts of some corporations to popularize free or underpaid labor sometimes lead to misunderstandings. Not long ago an article appeared in a magazine giving a very wrong conception of the Red Caps of Grand Central Terminal. Having been a Red Cap myself for over 16 years (resigning that position in February, 1926), and being subjected to the injustices which are still being practised toward the Red Caps, I feel that some effort should be made to clear the minds of the traveling public of the idea that a Red Cap is a well paid man. The public pays him and the public should know that it is on them that he depends for a livelihood. One would naturally ask why should these conditions exist. Space does not permit a broad explanation. One reason is that the Red Caps are an unorganized body. Even though a man may be working for 20 years or more, he can be discharged at a moment’s notice. He can be suspended for any length of time at the will of those in authority. If he exhibits a fair amount of intelligence he becomes a bad fellow. He is supposed to be off duty every other Sunday. If he is told to report on the Sunday he is due off, he has to do so, or lose his job. To give an instance of the helplessness of these men: A passenger arriving on the Empire State Express due at 10 P.M. failed to get a Red Cap one night. He reported it to the authorities and the result was that the day men, even those detailed on Vanderbilt Avenue who do not meet trains, and who were off between 5 and 7 P.M. were ordered to report for duty in the evenings just to meet that train and the Boston Limited due at the same time. If these trains happened to be late why the men had to remain until they arrived, and report for duty at the regular hour next morning. This was kept up for some weeks.

The collective spirit of these men is one of unrest and dissatisfaction, yet none dares to admit it openly. Every Red Cap knows that his place can be filled immediately. If he is a paid man, there are men applying for work every day who will fill his place for nothing. If every Red Cap in the Grand Central Station resigned, they could be replaced by double the amount of men within 24 hours.

Years ago a Red Cap had to sign a book of rules when he joined the force. Today there is no such thing as a book of rules governing the Red Caps. Rules are made according to the likes or dislikes of the authorities and can be broken at a moment’s notice.

If I may be permitted to express my opinion regarding the future of the Red Caps of Grand Central Terminal, I will say that the time is not far distant when organized labor will find its way into the ranks of this body of men. The question is, when that time comes, will we find colored men manning the station? Will those in authority remember those men who have worked in the Old Lexington Avenue Station? Men who cleaned the old station at night time for practically no wages at all, men who have been called upon to do the work of white men, when those white men were on strike? Will we find these old men in Grand Central at that time or will we find a well organized body of two or three hundred white men enjoying the benefits of a good salary, plus the remuneration they receive for their services to the traveling public? The future will tell, but for my part, I much prefer to see white men demanding the treatment of men, than to see colored men being treated as slaves.

The Messenger was founded and published in New York City by A. Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen in 1917 after they both joined the Socialist Party of America. The Messenger opposed World War I, conscription and supported the Bolshevik Revolution, though it remained loyal to the Socialist Party when the left split in 1919. It sought to promote a labor-orientated Black leadership, “New Crowd Negroes,” as explicitly opposed to the positions of both WEB DuBois and Booker T Washington at the time. Both Owen and Randolph were arrested under the Espionage Act in an attempt to disrupt The Messenger. Eventually, The Messenger became less political and more trade union focused. After the departure of and Owen, the focus again shifted to arts and culture. The Messenger ceased publishing in 1928. Its early issues contain invaluable articles on the early Black left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/messenger/v9n10-oct-1927-Messenger-RIAZ.pdf