A fine biographical introduction of Marat from German Communist Paul Friedländer for the Vioces of Revolt series.

‘Jean Paul Marat, the Man of the People’ by Paul Friedländer from Voices of Revolt No. 2. International Publishers, New York. 1927.

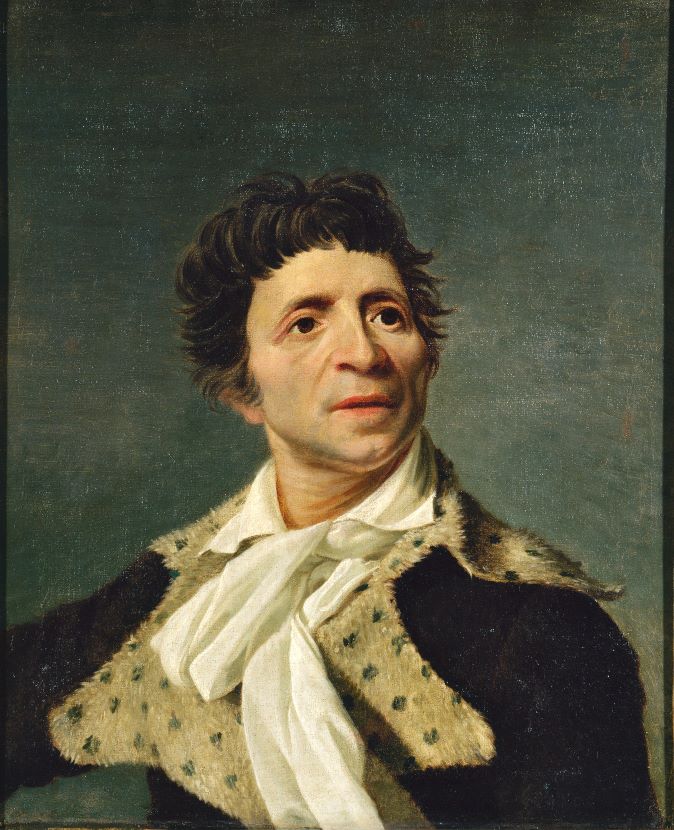

MARAT, the Man of the People, the tirelessly watchful eye of the people, of all the leaders in the years of Revolution the most viciously persecuted, and finally murdered by the nobility, hated and calumniated by bourgeois historians as a “bloodhound”–occupies one of the foremost places among the great men of the French Revolution. From the very first days of the Revolution, his struggles and his destiny were united more than in the case of any other leader with the struggle and the destiny of those “who really carried out the revolution,” “of the lower classes,” “of the propertyless whom the rich call the canaille” (to use Marat’s own words). It was Marat who recognized at the very outset, with his incomparable political acumen, the quality of the “constituent National Assembly” as a pacemaker for the “respectable” bourgeoisie, and simultaneously as an oppressor of the great masses of the people. He was the first to emphasize the class contradictions in the “third estate,” the first to become a passionate proclaimer of the hardships and needs of the wage laborers, apprentices, petty artisans, petty traders, and poor peasants. He was the first in whose person the will of the proletariat to engage in the class struggle was embodied. His memory must remain firmly anchored in the consciousness of the workers forever.

Marat–by calling a respected physician and scholar, while Robespierre, Danton and Desmoulins were lawyers–entered the political arena as a mature man, a finished personality, in which he differed from almost all the other heads of the French Revolution. Jean Paul Marat was born in Switzerland in 1743.

His studies–chiefly in medicine and the natural sciences–were carried on at Toulouse, Bordeaux and Paris, later in England, and Scotland. He was given the degree of doctor of medicine by the University of St. Andrews (Scotland) and termed a “quite prominent master of the sciences.” He practiced in London, a: respected physician. In 1774, he was made a member of the Grand Lodge of the Free Masons of England. After having issued a number of scientific writings he published in 1774–in English–a social and political polemic entitled The Chains of Slavery. In this book, still strongly influenced by the English and French philosophy of enlightenment of the eighteenth century, he attacks abuses of government by princes as the cause of social ills and demands the liberation of the people from the chains of slavery by means of a free parliamentary system. He also took active part in English politics by publishing an election leaflet.

When thirty-four years old, he returned to Paris as the court physician of the Comte d’ Artois, one of the leading members of the higher nobility. He continued to occupy is position for five or six years, after which he was glad to free himself from this situation of dependence. During this time, he published a: number of sensational writings on electricity, on fundamental questions of optics, and on light.

Among other things, he translated Isaac Newton’s Optics into French, and attacked Newton’s theory of color (as Goethe–who approved Marat’s position–also did later). He was obliged to struggle for years against the malaise of the scientific academies, a thing which embittered him considerably. His appointment to be the head of an academy of sciences about to be established in Spain was defeated by intrigues. In addition to his considerable scientific activity and his extensive correspondence, which he did not neglect even in the years of Revolution, he also published a serious political work which is indicative of his great breadth of view, the Plan for a Penal Legislation. In this work he appears as an opponent both of the crude materialism of his era, as well as of atheism, but demands greater liberties for the people and espouses an insurrection against the tyranny of princes and in favor of liberty of belief, and of society’s obligation to take care of the unemployed and for the erection of national workshops with compulsory labor (for giving employment to those who steal because of hunger and distress; these are to suffer no other punishment). The first call of the Revolution served as a turning point in his life: this was the convocation of the States General. The news of this step, as he himself informs us in a later address to the president of the Constituent National Assembly in 1790, made an “immense impression on him” then seriously ill, and brought about “a beneficent crisis.” In the last few years he had followed with despair in his heart the conditions in France, the irresponsibility of absolutism, the nation’s burden of debts, the decay of industry, the boundless extravagance of the court, the nobility and the church, at the expense of all the workers. At once–early in 1789–Marat composed an extensive pamphlet on the elections to the States General: The Gift to the Fatherland (Offrande a la patrie).

This work, composed in the clear, entrancing style that marks Marat’s writings, attempts to spur on the “third estate,” in spite of its motley social composition, to the performance of uniform and thorough reforms. The States General must establish the sovereignty of the nation in a new constitution; a permanent parliamentary committee must be installed, to which the ministers shall be responsible; freedom of the press and of associations, abolition of lettres de cachet, a radical reform of the penal law, a graduated tax on incomes and capital-all these are necessary.

Up to the time he wrote this book, Marat had been a theoretical reformer, like many other men of his day. Furthermore, he had remained a faithful adherent of the king; but now he changed–impelled by his political understanding, which was as acute as it was vehement, and by reason of the course of events–into a practical revolutionary who could no longer be deceived by “horse play” or “radical rhetoric” of any kind.”

An attempt to outline the role of Marat in the French Revolution involves also throwing light on the development of the French Revolution to its culmination, namely, the establishment of the authority of the Jacobins, from the point of view of the broad strata of the “third estate.”

Only two months after his Gift to the Fatherland, Marat issued a supplementary pamphlet in a much sharper vein. In the addresses to the “third estate” he not only scourges the crimes of the government, but also harshly criticizes the manner in which the States General were convoked and the nature of its membership. A broad mass movement had already begun in Paris early in 1789. The opposition of the financial and commercial bourgeoisie, of the factory owners, the guild masters, as well as of certain strata of the intellectuals–to the ruinous autocracy of Louis XVI and the court nobility, together with the reverberations of the peasant insurrections, had an inflammatory effect on the great masses of the population of Paris, the artisans, petty traders, apprentices, wage laborers, domestic servants, the unemployed. While the interests of these classes did not coincide in any way, they were none the less united by one common demand: that of being represented in the National Assembly and of thus having an opportunity to present their grievances. For all had been excluded from representation in the constituent body. Furthermore it is these classes that were hardest hit by the general economic collapse and by the high cost of living. Among the apprentices and wage workers, who must suffer more than others, by reason of low wages and the exploitation practiced by the “respectable citizens,” in other words, by the nucleus of the “third estate,” there begins a vague expression of resistance to the “respectable citizens.” This opposition is expressed in the “Petition of 150,000 Workers and Artisans of Paris” addressed to the States General, and putting the question: “Are we not citizens also?” It is also expressed in the “Grievances of the Poor Population,” which state plainly: “We are, to be sure, to be counted among the ‘third estate,’ but among the elected representatives there is not one of our class (sic!) and it seems that everything has been done only to the advantage of the rich.”1

In the “cahiers2 of the fourth order,” the wage workers demand recognition and representation as the “fourth estate,” because the bourgeoisie, who are declared to be nothing but wage exploiters and vampires, are advocating interests opposed to theirs.3

This vague discontent of the petty citizens and workers made its way to Marat’s ear, as is shown already in his Outline of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which appeared in the spring of 1789. Here, Marat is taking a step in advance, in demanding universal suffrage (for men), equal political rights for all citizens, recall of representatives by their electors. No doubt, Marat still accepts the basis of a guarantee of property, not of its abolition, but he does declare that great property differences jeopardize democracy.

The States General meet: the first phase of the Revolution begins. The “third estate” is constituted under the pressure of the masses as a National Assembly. The nobility and the clergy are obliged to submit willy nilly. Simultaneously, the court begins its counter-revolutionary machinations, which result in the storming of the Bastille by the lower strata of the population, on July 14, 1789. The Necker Government is formed and the abolition of feudal privileges is proclaimed in the night of August 4, 1784.

Marat recognizes the nature of the Revolution at this stage; he recognizes not only the subsequent threatening danger of counter-revolution, but he also understands that the revolution has been of advantage only to the upper strata of the bourgeoisie, to the rich, and not to the masses of the people. For this reason, Marat establishes, early in September, 1789, a periodical first published as the Publiciste parisien (September 12, 1789) whose name was changed on September 16 to L’ami du peuple (“The Friend of the People”). In this periodical, perhaps the most important of the many periodicals that then sprang out of the ground like mushrooms, Marat is the sole writer. Its existence continues up to his death. In the period of the Convention, beginning September 1792, it was called the Journal de la republique francaise, par Marat, l’ami du peuple.

At the very beginning, Marat is the first to enter the opposition against the government and against the National Assembly, attracting great attention thereby. Marat comes out boldly to attack the proposed limitation of the sovereignty of the people by means of a second chamber (a senate) and by means of a royal veto power. He demands that the mandates of the representatives in the National Assembly be considered as conditional. Should the delegates not discharge their duty, the people must have the right to recall them and declare their legislation as null and void.

Marat points out that the commercial bourgeoisie is attempting to exploit the national assembly for its own advantage and not hesitating to ally itself for this purpose with the crown, the nobility, and the church against the people. From the very beginning, he unmasks the activities of the triune group engaged in this work, namely: Necker, Mirabeau and Lafayette. Even while the entire population, including the Lefts, lies prostrate before these men, he predicts in detail their treason to the Revolution, their passing over to the enemy, to the royal power and the nobility, all of which was later to come to pass. (Marat’s Appel a la nation, “Appeal to the Nation”).

Marat is the first to point out, in his L’ami du peuple, that the National Assembly has done nothing to improve the public economy.

“People without reflection!…Why rejoice?…The state lies in its death throes; the workshops stand empty, factories are deserted, trade is at a standstill, the finances are demoralized…”4

The National Assembly does nothing to counteract this condition. Necker’s financial and economic policy merely makes the situation worse. The workers are unemployed and starving.

Marat is the first to recognize that the “great sacrifices” of August 4 are illusions, since the land rights and feudal rights have not been annulled for the common weal; they can merely be transferred, and this condition is of practical value only to the rich.

Marat’s role as an advocate of the poor, who have made the Revolution and who come off without any gains from it, becomes more important in the course of the Revolution. The Revolution does not bestow the suffrage on the propertyless; it denies them the right of organization, it grants them no minimum of subsistence, it crowds the unemployed into frightful compulsory labor colonies. It excludes workers from the National Guard, which becomes a guard of rich citizens. It incarcerates workers who strike or who make demonstrations for improved wages.

In the course of development, Marat’s political and economic views become clearer and clearer. His horizon broadens. Marat demands a cleaning up of the national apparatus and of the local apparatus, of all elements hostile to the people. He declares: “We must sweep out of the Hotel de Ville all the…public prosecutors, lawyers, academic professors, gentlemen of the courts, courtiers…the financial jobbers and speculators.”

Marat fumes tirelessly against the financial policy of Necker which burdens small incomes and the propertyless; he wages a polemic against the policy of inflation (the issue of assignats). “Shall the poor artisans, the poor workers, the poor wage laborers be fleeced…shall twenty million human beings be reduced to beggary…” merely to benefit the parasites on the nation and the community, the financial speculators, the tax farmers?

In January 1790, and in the spring of the same year, Marat issues his great polemics (the Denonciation contre Necker, and the Denonciation nouvelle contre Necker) in which he shows that Necker’s policy provides an easy path for grain profiteering and famine, and favors the traders and the rich, to the point of aiding the counter-revolution.

In his L’dmi du peuple, Marat declares himself more and more definitely and vehemently in favor of the propertyless. (See, in this book, the passionate Open Letter to Desmoulins, whose fundamental note is struck in the words: “The demands of those who have nothing on those who have everything.”)

He demands for them the same political and material rights as for the rich, particularly the active and passive right of suffrage without regard to amount of taxes paid, and the representation of the masses in all representative bodies, the state, the department, the commune. If this right is not granted them, the Revolution will proceed until they obtain it by force. Marat here displays profound insight into the historical evolution:

“Laws, moreover, have authority only in so far as the nations are ready to submit to them; if the nations have been able to break the yoke of the nobility, they will also be able to break the yoke of wealth…The propertyless will be able to avail themselves as well of the principles of liberty and equality in order to deprive the wealthy of their privileges and their booty, as did the “third estate’·’ when it destroyed the privileges of the nobility.”5

Marat demands higher wages, the abolition of all head taxes and consumers’ taxes, a general supplying of cheap bread to the population.

Soon after the appearance of the first issue of L’ami du peuple, those attacked in its columns began their campaign of persecution, particularly Mayor Bailly, the Commandant of the National Guard, Lafayette, and the Government resorts to the Court of the Chatelet for this purpose. For three years Marat is obliged to live and work “illegally.” He is hunted from quarter to quarter, is obliged to live for months in moist, dark cellars, even to flee to England for a period. But his energy is unflagging. His writings are confiscated, his presses destroyed, his numerous letters to the National Assembly are burned. He is overwhelmed with bucketfuls of calumniation. He continues to work without giving himself sleep and recreation, although his health has been seriously affected. His faithful lover, Simonne Evrard, stands by him bravely (until his assassination breaks her completely).

The French Revolution, meanwhile, had entered upon a new stage. After a forced transfer of the royal family to Paris, there came the period of counter-revolutionary machinations and the attempts at counter-revolutionary insurrection. Again Marat is at the head of those who demand the safeguarding of the Revolution by other means, if necessary, even by dictatorial and terroristic means. In a handbill (Sommes-nous trahis? of July 26, 1790) printed in this book, he demands a general arming of the people, a disarming of the court, the beheading of the leaders of the counter-revolution. This creates a profound impression. There is a general wailing and gnashing of teeth, but Marat speaks–being a vehement yet a humane champion of the Revolution–not through love of bloodshed but because of his political clarity. Marat, the consistent democrat, recognizes that a (mild) terror is the sole means for safeguarding and expanding the work of the Revolution. He who “could not bear to see an insect suffer,” wishes to prevent whole oceans of blood from being shed later, as a consequence of “false notions of humanity,” of a foolish consideration for the feelings of the bloodthirsty enemy,” and he prophesies the dreadful raging of the counter-revolutionists if they should ever again gain the upper hand. Not long after the publication of this document, the correctness of Marat’s view received its first confirmation. The National Assembly and the royalist officers at Nancy ordered bloody massacres costing thousands of lives, merely because the garrison at Nancy had demonstrated in protest against corrupt feudal military officers.

Soon the storm gathers about France. The emigres stir the European powers to action. The campaign of the monarchs against revolutionary France begins. The king, the court, the Right section of the National Assembly, all conspire with foreign powers against the Revolution. The parties within. the National Assembly are more sharply differentiated. The king makes his unsuccessful attempt at flight, leaving behind a counter-revolutionary manifesto. Marat calls for the overthrow of the king, the smoking out of the court. It is all in vain. The counter-revolutionary groups still have the upper hand. The treasonable king is soon again restored to all his rights.

Marat, who had been obliged to flee to England for a few months in the autumn of 1791 now draws his support more and more from the lower strata of society. He becomes mentally clearer as to the opposition of class interests within the “third estate.”

The safeguarding of the Revolution and its political and social progress are assured only by the lower strata of the population.

Early in October 1791, the “Legislative Assembly” takes the place of the “National Assembly.” This assembly was elected on the basis of a privileged suffrage right held by the wealthy. The Girondists have a great influence upon it. Marat, who had returned to Paris in February, 1792, again begins his campaign of exposure against the vacillating faction of the Girondists, who speak for the interests of the commercial bourgeoisie. He also antagonizes the constitutional group, who are trying to maintain the constitutional monarchy, with Louis XVI, the “crowned perjurer” and “traitor to his country,” in power. “The second legislation is not less rotten than the first,” writes Marat: The policy of hostility to the workers, the policy of profiteering, these make conditions worse and worse. In addition, the king interposes his veto against the resolutions opposing the emigres and clergy which have been passed by the assembly in response to a general pressure from the masses.

High prices and hunger are on the increase. So is the general discontent.

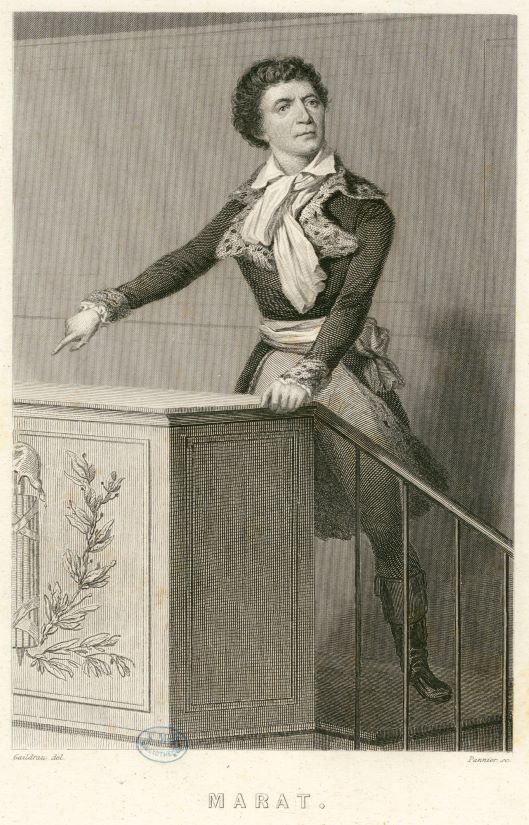

Marat agitates in the workers’ sections, where the discontent is strongest, as a result of profiteering, of unemployment, and of the general policy of hostility to the petty bourgeoisie and the workers. He plays a prominent part in the Left Club of the Cordeliers, soon also in the Jacobins. The authorities fret and fume because they are unable to get the better of him. Marat demands a thorough revision of the national and communal apparatus. He demands the establishment of the republic. But a new, truly democratic order, can only be established by force. “Do you really believe that you can change the inclinations and habits, the manners and passions, of the ruling class, by the preaching of moral principles?”

The court, allied with foreign powers, makes one fruitless counter-revolutionary attempt after the other, and as a result, the Tuileries is stormed on August 10, 1792, and the king taken prisoner. The Republic is proclaimed. This action is an action of the masses. The Communal Council is deposed. A new Communal Council of revolutionary membership is elected. Marat is elected as a member of the Committee of Public Safety which is the result of his motion. Now at last, in the third phase of the Revolution, Marat finds it possible to appear publicly as a protagonist. Danton, Robespierre, Marat, bring about the establishment of the flying court, which disposes swiftly of the most dangerous ringleaders of the insurrectionary attempts. These are the so-called “September murders.”

The National Assembly is dissolved. The National Convention is convoked. Marat becomes a member of the Convention. The name of his paper is changed to the Journal de la republique francaise.

The motto printed at its head is: Ut redeat miseria, abeat fortuna superbis (“In order that misery may be diminished, the property of the wealthy must be abolished”). This motto is a clear indication of Marat’s role in this phase of the French Revolution.

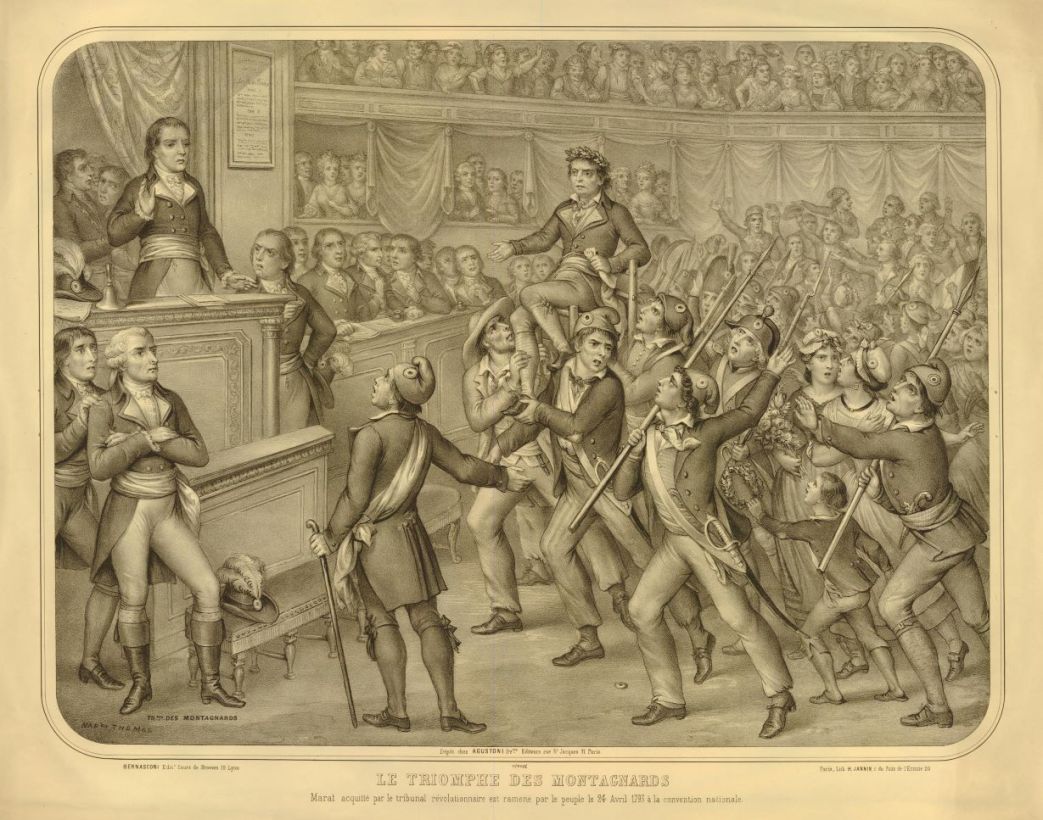

In the Convention, the Jacobins succeed in carrying out their demand for a real political democracy. The Girondists make this concession in order to maintain themselves at the top, but in vain! Marat continues his struggle against the domination of the Girondists, whose vacillation and whose connection with the counter-revolution endangers the Revolution in the provinces. He declares that a “dictator,” whose duty however shall be not that of conducting the national affairs but that of disarming the counterrevolutionaries, must be appointed. The Girondists wish to draw up an indictment against Marat and Robespierre through the Convention. The Convention ref uses to do this. Marat, who enjoys the passionate affection of the broad masses in Paris, who call him their “prophet” when he permits them to express themselves in his paper, will not be intimidated. Marat’s influence in the Paris Commune becomes an incisive one. He wages a campaign against food profiteering, for which the policy of the Girondist government is chiefly to blame. He proposes a number of measures for alleviating the lot of the workers. A militant article in his newspaper (which is printed in this book) on the subject of plunderings that have taken place, arouses the Girondists to the extreme, but they dare not proceed against him. Since the Gironde continues its “respectable bourgeois policy” and opposes no serious resistance to the counter-revolutionary insurrections in the interior of the country, particularly in the Province of La Vendee, nor to the great military intervention from abroad, Marat emphatically demands its elimination. When the Girondists finally succeed in having him summoned before the Revolutionary Tribunal (on April 24, 1793) to answer a charge of “incitation,” he is unanimously acquitted and led home in triumph through the streets of Paris, accompanied by almost the whole population.

This trial is a prelude to the downfall of the Girondists. Marat is at the head of the Jacobin Club. The situation in France has reached its most critical point. The Revolution is in the greatest danger-Marat organizes the defeat of the Girondists. In the last days of May, 1793, the entire working population of Paris rises. Together with the Communal Council and led by Marat, it forces the arrest of the leaders of the Gironde (on June 1, 1793), as a result of whose policy the young republic had been brought to the brink of ruin. The Convention now proceeds to take steps in accordance with Marat’s most important demands for the safeguarding of the Revolution. The rule of the Jacobins and of the Committee of Public Safety is established. The Convention succeeds in the space of a few months in safeguarding the republic within and without.

Marat became seriously ill early in June. The terrible life he had been obliged to lead for years now took its revenge upon him. He is unable to attend the sessions of the Convention, but from his sick bed sends daily letters to that body.

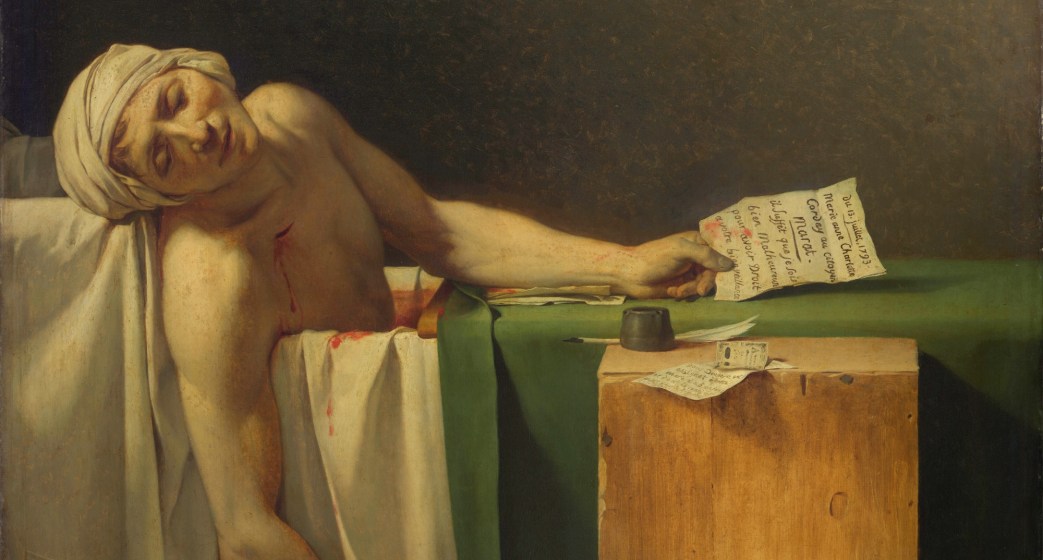

The hatred and rage of the counter-revolutionaries concentrates on Marat. From Caen, in La Vendee, where an opposition government has been formed, the royalists send their fanatical adherent, Charlotte Corday, to murder Marat. She obtains access to his rooms by misrepresentations of various kinds, on July 13, 1793. She stabs to death the defenseless man, who is sitting in his bath, now a practice demanded by his skin disease, and is herself decapitated a few days later.

Marat died without leaving any property. His tragic death horrified the entire population of Paris, which was fanatically attached to him. Even one of the most read bourgeois-reactionary histories of the French Revolution has the following to say: “Marat after he was murdered was even far more the object of the enthusiastic worship of the population than during his life. His name was invoked in public squares as that of a saint; his bust was exhibited in all patriotic societies, and the Convention was obliged to grant him the honor of interment in the Pantheon.”

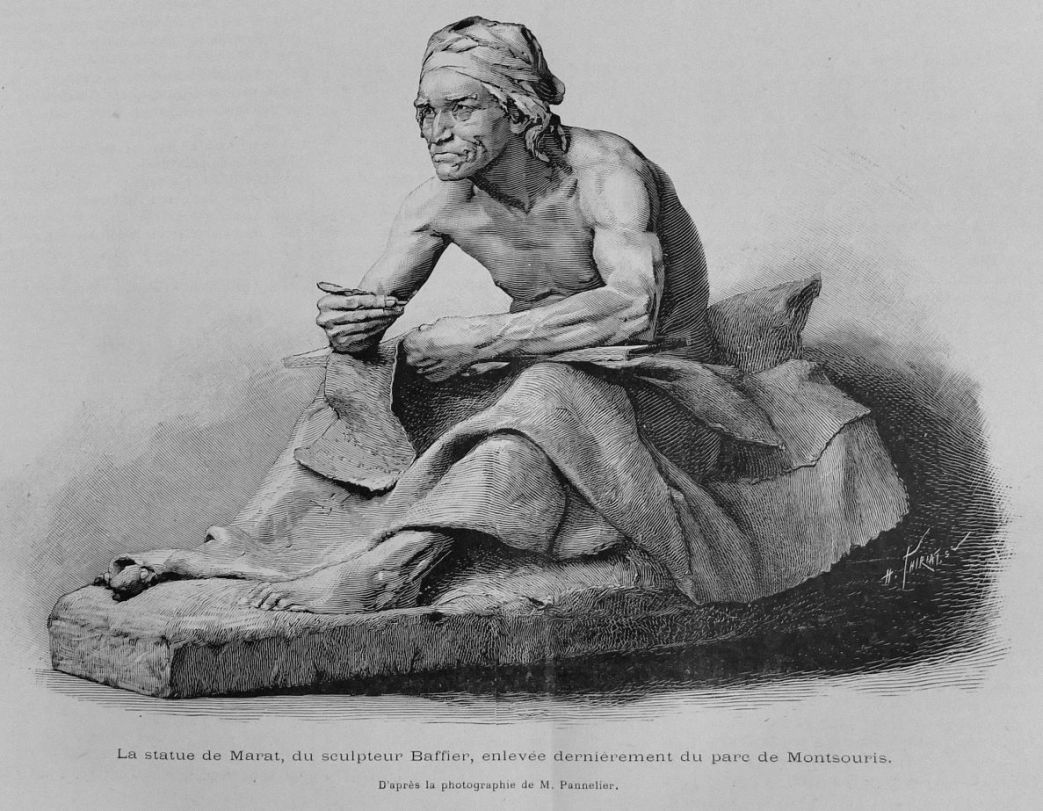

Marat’s murder was a severe blow to the French Revolution, which lost in him probably its best and clearest thinker. The counter-revolution did everything it could to besmirch Marat’s memory. It destroyed his monument in the Pantheon. It burned his correspondence and most of his writings. Every painting, every inscription, which suggested his name was destroyed (including a work by the great painter David). Charlotte Corday was lauded to the skies. Yet, an honest historical presentation cannot do otherwise than admit that the soaring flight of the French Revolution will be associated forever with the shining name of Marat.

Marat was a revolutionary pioneer of the laboring masses. In the. Hall of Fame that the workers will one day dedicate to their noblest pioneers, Marat will hold. a place of honor.

NOTES

1. Karl Grunberg: Archiv fur die Geschichte des Socialismus und der Arbeiterbewegung, vol. I, 19n, p. 447.

2. The cahiers (Fr. cahier means notebook) were the written instructions issued by the electors of the three estates to serve as a guide for their representatives in the States General of 1789.

3. Loc. cit.

4. Heinrich Cunow: Die Partden der grossen frainziisischen Revolution und Presse, Berlin, 1912, p. 325.

5. Heinrich Cunow: op. cit., p. 329.

Writings and Speeches of Jean Paul Marat. Voices of Revolt No. 2. International Publishers, New York. 1927.

Contents: Biographical Sketch by Paul Friedlander, A Fiendish Attempt by the Foes of the Revolution (July, 1790), Our We Undone? (July 26, 1790), A Fair Dream and a Rude Awakening (August 25, 1790), Nothing Has Changed! (July, 1792), The Friend of the People to the French Patriots (August, 1792),Marat the People’s Friend to the Brave Parisians (August 26, 1792), Marat the People’s Friend to the Faithful Parisians (August 28, 1792), Guard Against Profiteers! (February 25, I793), Letter from Marat to Camille Desmoulins (June 24, 1790), Letter from Marat to Camille Desmoulins (August, 1790), Explanatory Notes. 78 pages.

The second in the Voices of Revolt series begun by the Communist Party’s International Publishers under the direction of Alexander Trachtenberg in 1927.

PDF of original book: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/voices-of-revolt/02-Jean-Paul-Marat-VOR-ocr.pdf