Political and social life in the United States was transformed by the ‘Great Migration’ of millions of Black workers from the tenant farms and plantations of the Jim Crow South to the rapidly industrializing cities of the north. Jay Lovestone looks at some of the many implications for the class war.

‘The Great Negro Migration’ by Jay Lovestone from Workers Monthly. Vol. 5 No. 4. February, 1926.

AS a result of the world war, the class divisions and the relation of class forces in the United States changed deeply.

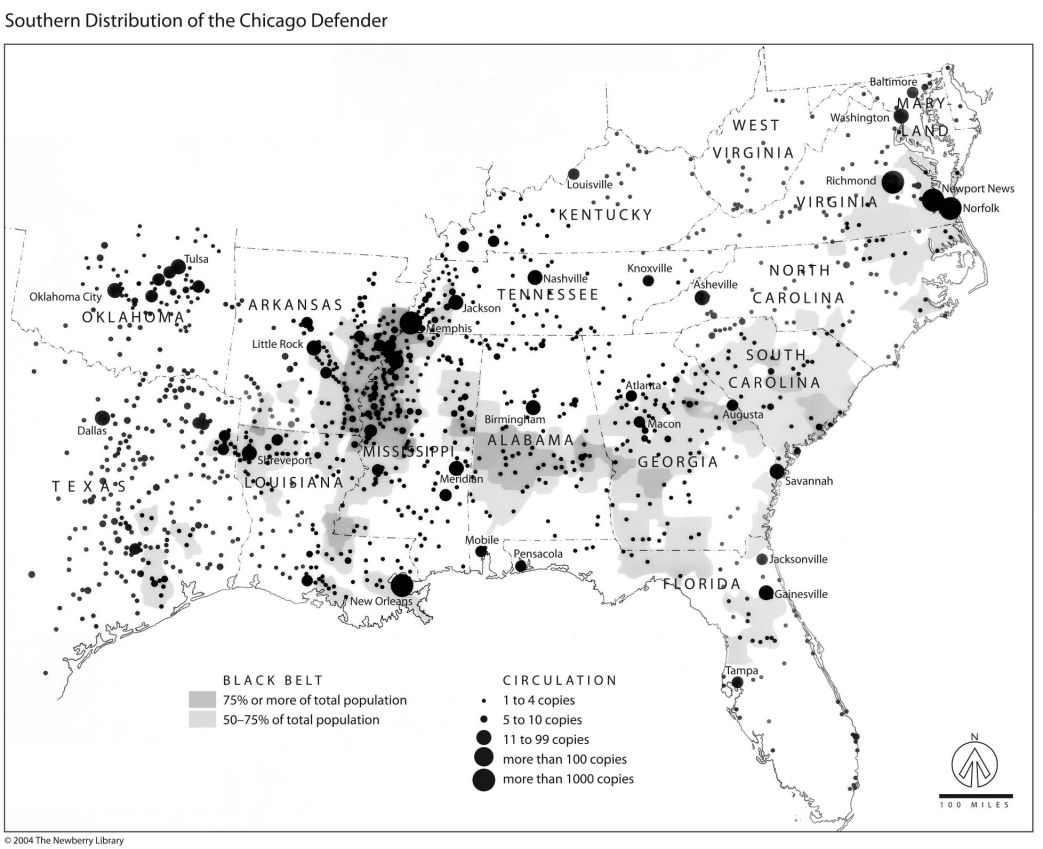

A most striking phenomenon of this character is the mass migration of the Negroes, mainly from the cotton plantations of the South to the industrial centers of the northern and eastern states. John Pepper characterizes these migrations strikingly as “unarmed Spartacus uprisings” against the slavery and the oppression of the capitalist oligarchy in the Southern states. This phenomenon is of tremendous economic, political and social significance for the whole American working class.

Co-incident with such dynamic forces influencing the class relations in the United States, is the increasing world supremacy of American imperialism.

America has become the center of the economic and cultural emancipation of the Negro. Here this movement forms and crystallizes itself. Therefore it is especially important for the success of the efforts of the Comintern and the Red International of Labor Unions striving to mobilize the millions of Negro masses of Africa, Costa Rico, Guatemala, Colombia, Nicaragua, and the satrapies of American imperialism such as Porto Rico, Haiti and Santa Domingo, against the world bourgeoisie, that the movement of the Negroes in the United States should develop in a revolutionary direction.

Extent of the Negro Migration.

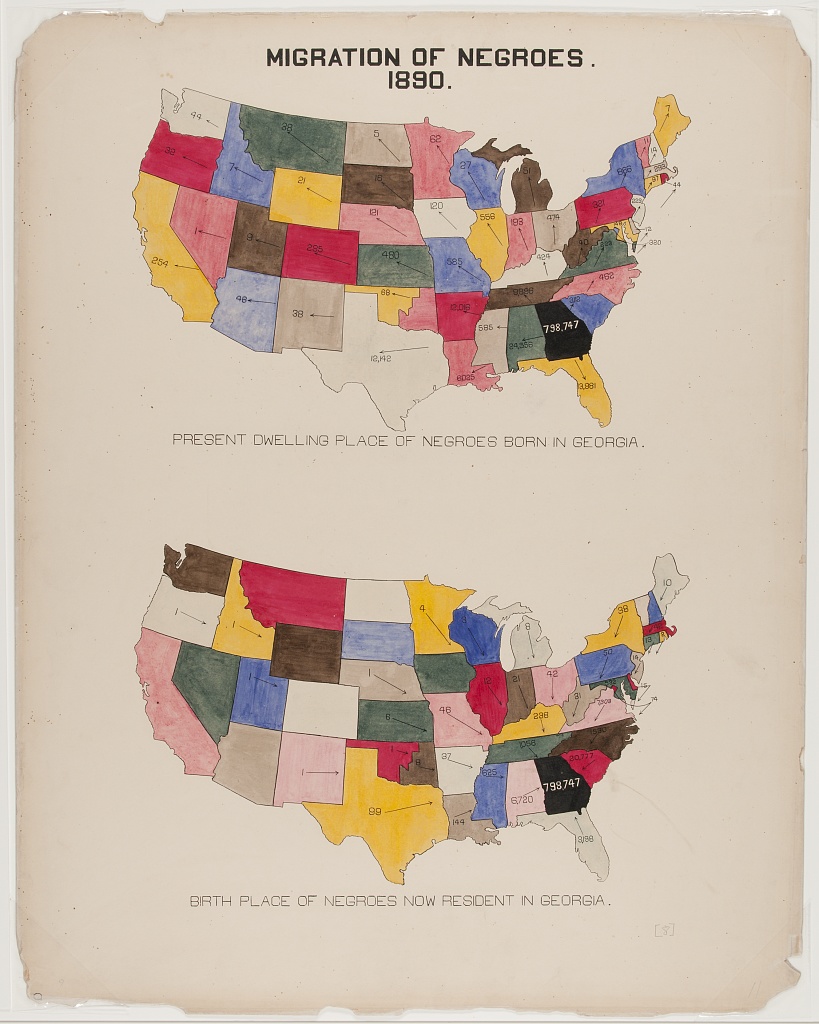

According to the last census (January, 1920) there were in the United States 10,463,131 Negroes of whom eight millions were then still in the Southern states. The recent migration of the Negroes from the South took place during two main periods. The first was 1916-1917 when, because of the entrance of America into the world war, a strong demand for skilled labor power arose and whole Negro colonies and Negro villages migrated to the northern industrial centers. This migration totaled approximately four hundred thousand. The second period, 1922-23 coincided with the peak of American industry that followed after the economic crisis of 1920-21, and is to be traced back to the great demand for unskilled labor in the Northern districts.

According to the findings of the United States Agricultural Department, the period since 1916 has seen an annual migration of 200,000 Negroes from the Southern states, as against ten to twelve thousand annually for the period before 1916. In the four years from 1916 to 1920 between 400,000 and 730,000 Negroes left for the North. In the period from 1916 to 1924 the figures reached one million. The influence of this upon the concentration of population is obvious from the following figures: In 1910 the Southern states included 80.68% of the Negro population of America, while in 1920 only 76.99%. In four of these eleven states, the decrease of the general population from 1910 to 1920 was primarily due to the migration of the Negroes.

In 1923, 32,000 or 13% of the colored agricultural workers-left Georgia for the North. In the same year, there migrated from Alabama 10,000, from Arkansas, 15,000, and from South Carolina, 22,700 Negroes.

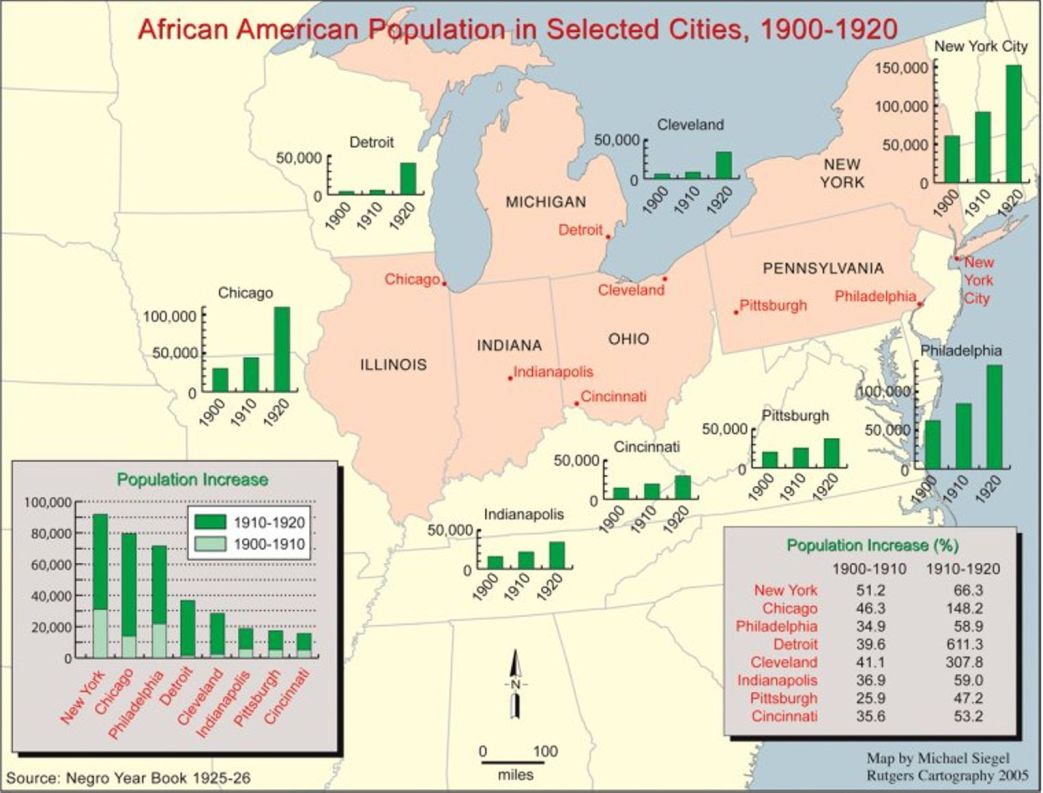

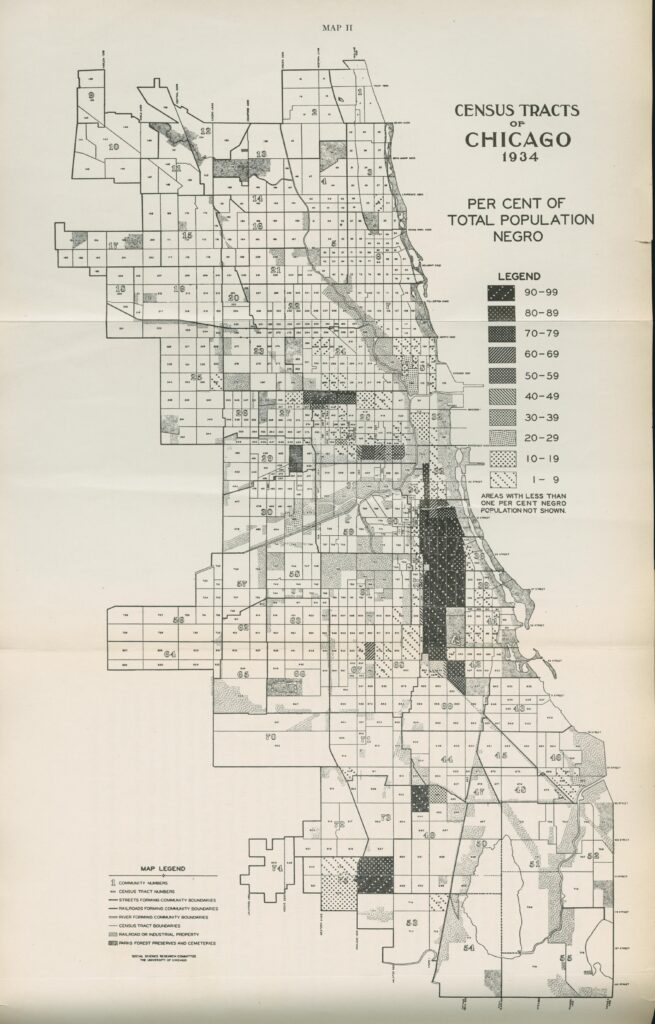

On the other hand, the Negro population of the Northern industrial city, Detroit, the greatest automobile center, increased in the period of 1910 to 1920 from 57,000 to about 90,000 and of Chicago, from 109,000 in 1919 to 200,000 in 1924. The strength of this migration from the South is evidenced by the fact that records show that in one day 3,000 Negroes passed thru a railroad station in Philadelphia. And this was not unusual. The mass of the emigrants consisted of agricultural workers and small tenants.

Because of the lack of labor power, many cotton and fruit plantations had to change to cattle breeding and dairying. According to the investigation of the Bankers Association of Georgia, there were, in 1923, in this state, no less than 46,674 deserted farms and 55,524 unplowed plots of land. Furthermore, on account of the migrations there was a loss of national wealth to the state amounting to $27,000,000.

The bourgeoisie and the big landowners in the southern states naturally at first resorted to strong measures against the mass exodus of their slaves. Thus in Georgia, for example, a law was passed according to which the “hiring of workers for other states, thru private persons or organizations is to be considered as a crime.” The plantation owners in Tennessee forced their government to put all those Negroes in custody who registered themselves in unemployment bureaus. In South Carolina and Virginia, all agents who were to obtain workers for other states had to pay a special license fee of $2,500 on the pain of suffering greater fine or imprisonment.

Causes of Migration.

The most important causes for the migration of Negroes from the South are the following:

1. The oppressive conditions of life and work of the Negro population, consisting mostly of tenants and agricultural workers.

2. The boll weevil plague in the cotton plantations.

3. The general agrarian crisis which forced the tenants in the South, as well as in the northern states, to look for work in the cities.

4. The deepgoing dissatisfaction among the Negroes in the South, especially after the world war.

5. The intense development of industry in the northern states, as a consequence of the world war, coupled with the immigration ban, as a result of which the demand for unskilled labor power grew tremendously.

1. Living and Working Conditions of the Southern Negroes.

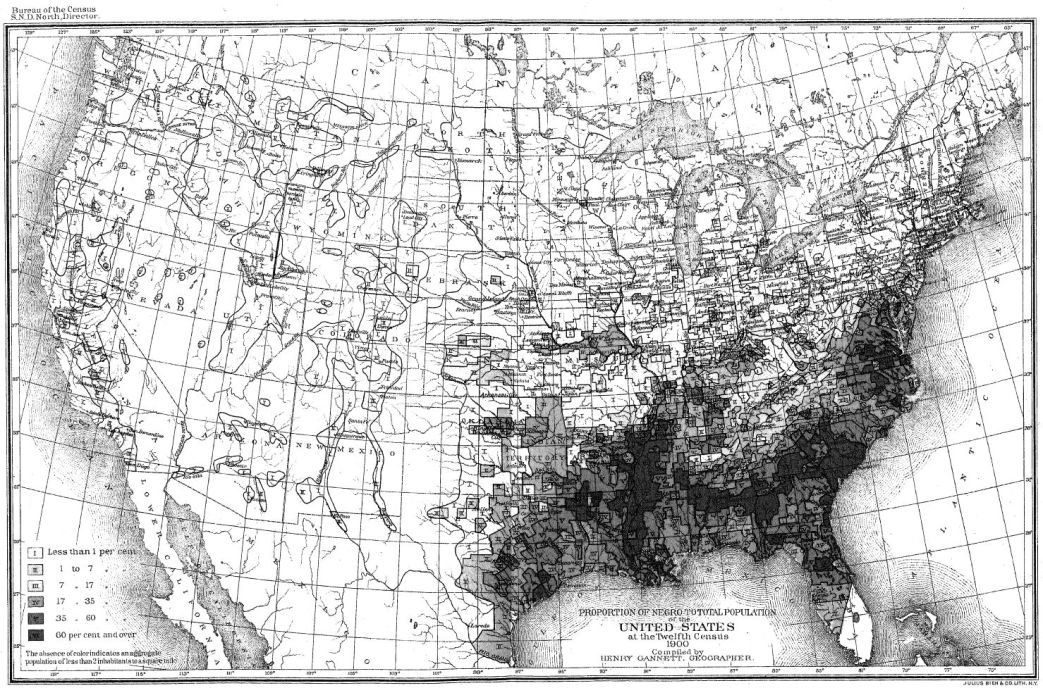

Most of the labor power in cotton production in the South has been Negro. In the period from 1880-1920, the percentage of plantation owners in the cotton belt sank from 62% to 49.8%. Seventy to ninety per cent of the cultivated land in the cotton districts of Georgia, South Carolina and Mississippi are rented by Negro tenants. In Mississippi 60% of all cotton farms are worked by Negroes, of whom 85% are tenants.

The tenants have not the slightest prospect of ever acquiring the possession of the land on which they work—a prospect that is still in the realms of possibility for the white farmer in the northeastern states, altho even here such prospects are now under ever growing difficulties. For the Negroes, the status of tenant is unchangeable. Leading a miserable existence, the Negro tenant is in the rarest cases able to provide his children with an elementary education. Thus, in 1923 in the state of Georgia, the appropriations for the schools for Negroes who at that time composed 45% of the population reached the total of $15,000 as opposed to the appropriation of $735,000 for the whites. We must add to this the usurious credit system which still more diminishes the scanty earnings of the tenant. The prices of the commodities bought by Negro tenants on credit are on the average seventy percent higher but in Texas it is 81% and in Arkansas 90%.

As a rule, the Negro tenant has a claim to only a half of the product of the labor of his relatives or others whose help he can obtain. Of this, the owners are legally empowered to deduct for supposed allowances and services by the land barons for means of life, clothing, medical help, etc. Many landowners are at the same time also merchants. Since written agreements are entirely unusual, the Negro is thus further uniformly swindled in the most shameless way.

The Negro masses are exploited so intensely that they are often more miserable than under chattel slavery. The status of the Negroes, their working conditions, and their sufferings, are illustrated in the following quotation from a report of the National Association of Manufacturers, of October 7, 1920: “The bad economic exploitation in these cases indicates a slavery many times worse than the former real slavery. Thousands of Negroes who have been working all their lives uninterruptedly are not able to show the value of ten dollars, and are not able to buy the most necessary clothing at the close of the season. They live in the most wretched condition… and are lucky to get hold of a worn out pair of boots or some old clothing…”

Judge S. O. Bratton who was able to obtain in Littke Rock, Arkansas, an accurate picture of the relations between the whites and the blacks, writes as follows: “The conditions today are worse than before the American Civil War… The system of exploitation is carried to such a point that most Negroes can hardly keep themselves alive upon their earnings. The plantation owners maintain so-called ‘commission businesses’ in which the prices of commodities are fixed at the order of the plantation inspectors. The Negroes are prevented in every possible way from keeping an account of the wares taken by them.”

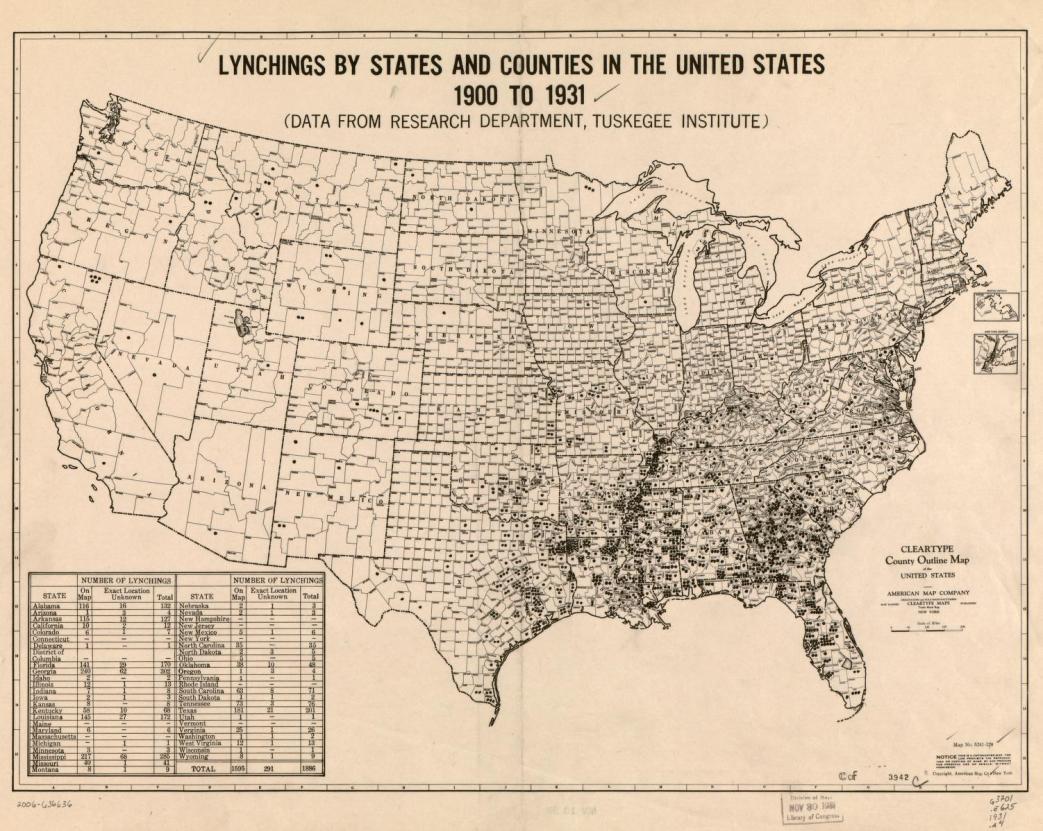

Another big source of misery is to be found in the “lynch law” and the terror of the Ku Klux Klan. In the January 1924 issue of the North American Review we have an illuminating report of Howard Snyder who spent many years in the plantation districts of Mississippi. Mr. Snyder says: “…If we add the cruel lynch law which is responsible for the murder of many Negroes burned alive, of whom we never hear in our great newspapers, and if we keep in mind that the Negroes working on the plantations are helpless and defenseless beings who are thrown into panic at the very mention of the Ku Klux Klan, then we will be able to understand the other causes of the mass migration. Nowhere in the world is there among the civilized peoples a human being so cruelly persecuted as the Negro in the South. Almost every day we read that some Negro was baited to death with dogs or whipped to death, or burned alive amidst the howls of huge crowds. How they could ever cherish the hope in the South that these people would suffer all this without protest when twenty dollars, the price of a railway ticket, can be sufficient to free them from this hell, passes my understanding.”

2. The Boll Weevil Plague and the Agricultural Crisis.

The boll weevil plague which recently visited the cotton plantations, has been a tremendous factor in changing the South. According to the approximate evaluation, the damages wrought by this pest in the years 1917-22 amounted from $1,600.000,000 to $1,900,000,000. As a consequence of this, cotton-cultivated land grew markedly smaller. Thus many black workers and tenants were forced to go to the North.

3. The World War and the Negro.

This wretched system existed prior to the world war. The Negroes were dissatisfied even before the world war. Yet it was the world war with its consequent fundamental economic changes and the Negro migration as a result of the rapid industrialization in the North and East that gave special impetus and created favorable opportunities for a wave of intense dissatisfaction among the Negro tenants and agricultural workers.

We must not underestimate the deep going change in the ideology of the Negro masses called forth by the world war. Whole generations were, so to speak, tied down like slaves to the soil. To them, their village was the world. And now, suddenly, hundreds of thousands of them (376,710) were drawn into military service. Over 200,000 were sent across and returned with new concepts, with new hopes, with a new belief in their people. Their political and social sphere of ideas broadened. Their former hesitancy and lack of decision was now leaving them. The Negroes were stirred en masse and set out to carry thru their aspirations, left their miserable shacks and went to look for better working and living conditions.

Simultaneously, the immigration of European workers into America was practically ended by the world war. In the post-war period, strict legal measures were taken for the same end. In this way, one of the best sources of the stream of unskilled labor was dried up. Thru the world war, however, the development of American industry made mighty steps forward and with this the demand for labor power rose. The industrial reserve army had to be filled up and the bourgeoisie of the North turned to the Southern states. In the Negro masses they saw a fitting reservoir to supply their gigantic factories of the northern and eastern states.

To illustrate how the capitalists looked upon the Negro problem in this phase of development, we have the following quotations of Blanton Fortson in a recent number of the Forum: “Disregarding his low stage of development, the undesirable immigrant is characterized by all those traits which are foreign to the Negro. He is permeated with Bolshevism. He understands neither the American language nor the American employers, contracts marriage with American women, multiplies very fast, so that finally, if the door is not closed to the stream of people of his kind, the real native workers will be suppressed by them.

“In normal times, there always exists in the industrial centers a demand for unskilled labor. Where can the North find this? To import unskilled workers from eastern and southern Europe means to increase the number of inferior people in America (To this apologist of capitalism, the ‘people permeated with Bolshevism’ are inferior. J.L.) If, however, we make use of the Negroes for this purpose, then we will simply redistribute the people of a lower race already existing in the United States and not increase them; in fact, diminish them.”

A more open declaration as to how the ruling class in America fills up its industrial reserve army with the help of the South and in this way lowers wages could hardly be found.

The Negroes who are tenants or agricultural laborers naturally seek to escape from their oppressive condition in the South. Better wage and working conditions in the North, somewhat more favorable educational facilities, and the illusory hopes of finally escaping from their difficulties are the motives of the Negroes in their migration. This phenomenon is one of the most significant in history. Today a Negro quarter can be found in nearly every one of the smallest towns of the northern states.

The Results of the Migration of the Negroes

1. The Improvement of the Standard of Living.

No one can question the fact that thru this migration of the Negroes the standard of living of the colored workers and peasants has been considerably raised. In comparison with the conditions confronting them in the southern states, before 1914 the colored workers today certainly have more opportunities to dispose of their only possession, labor power. Moreover, the mass exodus from the South has forced the ruling classes in the cotton fields to ameliorate the cruel treatment of their agricultural workers and in many cases even to raise their wages. The strong demand for colored workers has raised their price.

2. The Strengthening of Race Consciousness.

A further result of the mass migration of the Negroes is the development of a stronger race consciousness. Since hundreds of thousands of colored people have freed themselves from the yoke of slavery in the South, their pride and their confidence in the race have grown. The Negroes have begun to organize themselves. They are now taking up the struggle against their oppression in a more organized fashion. This is one of the real meanings of the still organizationally weak American Negro Labor Congress.

It is, therefore, no accident that in the recent years lynching has been on a decrease. For example, in 1892, there were 155 Negroes murdered in the United States; three decades later, 1922, only 61; and in 1923, only 28, while in 1924 there were only 16. This is partly to be traced to the changed attitude of the capitalists. But primarily it is to be attributed to the fact that of late Negroes have been offering more effective resistance to their oppressors.

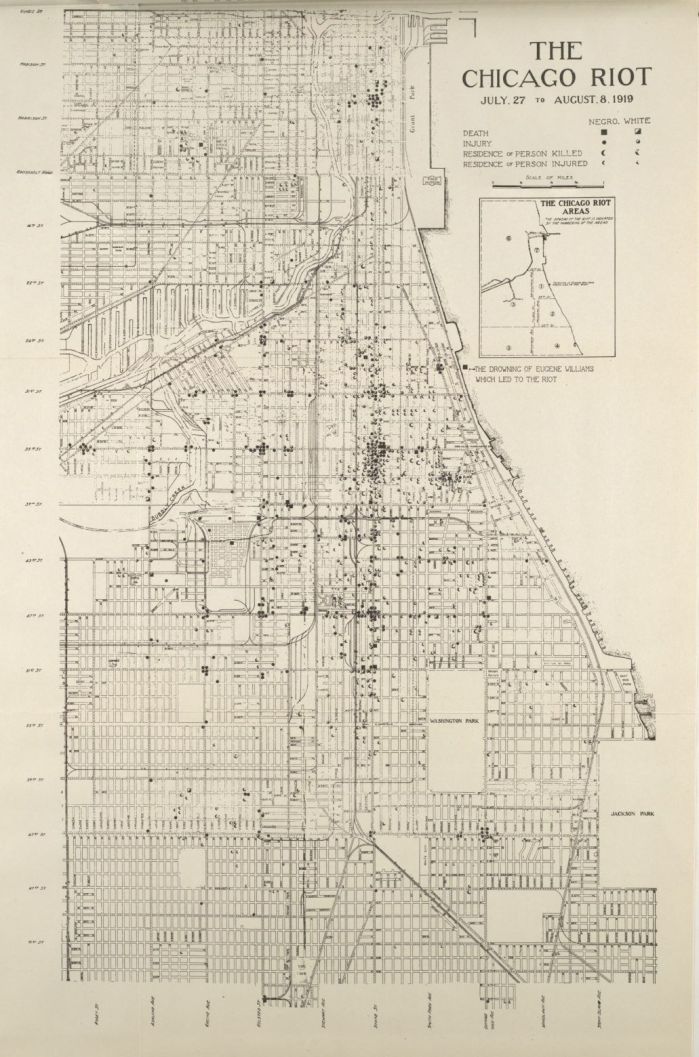

In October, 1919, for example, the colored tenants in Phillips county, Arkansas, rose up against their oppressive exploiters. It went as far as a bloody battle in which five whites and seventeen Negroes were killed. Also in Charlestown, West Virginia, Tulsa, Oklahoma, we had similar revolts. Furthermore, the Negro uprisings in the Northern centers, Chicago, Omaha and Duluth, were in a certain sense also the evidence of a strengthened race consciousness,

3. Concentration of the Negro Proletariat.

The migration of the Negro proletariat to the industrial cities of the North hastened its concentration. As evidence, we can point to the growing number of colored people living in the cities. In the last 20 years this rate of increase among the colored workers has grown much faster than among the whites. Whereas the white urban population was 43.3 per cent of the total population of the United States in 1900, 48.1 per cent in 1910 and 53.3 per cent in 1920, the following relations obtained for the colored population: 1900—22.6 per cent, 1910—27.3 per cent, 1920—-34.2 per cent. In 1920 more than 50 per cent of the Negro population in 27 states was found in the cities. With the white population only fourteen states showed fifty per cent or more living in the cities.

This tendency also prevails in the South, despite of the mass migration of the Negroes. For example, in the state of Mississippi the total number of Negroes fell by 75,000 from 1910 to 1920, the colored urban population increased by 3.4 per cent. Above all, the social composition of the Negroes has changed extraordinarily. Before the migration, the overwhelming majority was employed on the cotton plantations, today the greater proportion work for the industrial concerns. In the North, the Negroes had formerly been engaged as domestic help. Now, however, they are dominantly employed in heavy industry.

The Significance of the Migration.

In the South there is to be found approximately one quarter of the total population of the United States. Therefore, this migration is of tremendous economic, political and social significance for the entire country.

1. The Industrialization of the South.

Up to now the operation and organization of the cotton plantations were on an extremely primitive level. It was largely because of the migration of the black workers that the bourgeoisie were forced to reorganize their cotton culture and use machinery on a larger scale. Besides, the capitalists were forced to pay more attention to the natural resources of the southern states. This also hastened the industrialization of this section of the country.

2. The Negro as a Political Factor.

The mass migration of the Negroes to the North has increased their importance as a political factor. It is clear that their votes are of great importance in the elections of the northern industrial states. In the South the Negroes are very often deprived of their suffrage upon this or that pretext. In the North such disfranchisement is not so open or prevalent. From 1910 to 1920 the number of Negroes with votes (from 21 years up) increased in New York from 95,177 to 142,580; in New Jersey from 58,467 to 75,671; in Ohio from 72,871 to 126,940; in Indiana from 39,037 to 53,935 and in Illinois from 74,225 to 128,450. The Republican as well as the Democratic Party made the greatest attempts to win these voters for themselves in the northern industrial centers.

3. The Negro Question—a National Problem.

Thru the migration of the Negroes to the North the Negro problem did not lose any of its significance for the United States as a whole. On the contrary, it gained importance inasmuch as it became a question of national significance. In practically every industrial center the question of the segregation of the Negroes, their segregation in separate quarters of the city, stood on the order as an acute problem in some form or other. Thus, in the last report of the American Ass’n for the Advancement of the Colored People, it said, “In 1924, the most significant question was the creation of separate schools, of separate city quarters for the colored population of the United States.”

The broad masses of the Negroes migrating to the North have to a great extent recognized that the illusions which caused them to look upon the Northern states as a paradise were painfully unfounded. The apparent social and political equality of the Negro with the rest of the population of the North had only the slightest pretense to existence in fact so long as the Negroes constituted only a small minority.

The more the Negro problem takes on a national character the more important a role does the South begin to play in the economic and political life of the United States. To the working masses the Negro problem appears on first consideration as a class and racial question. But we should not forget that the basis of the class principle and not the racial principle, must serve as our point of judgement in this instance. In short, the mass migration has not solved the Negro problem in the United States. On the contrary, the great Negro migration has placed this problem before us with greater clarity.

We point to the plans to isolate the Negro population in the northern states, to the Negro revolts, as well as to the expulsion of the Negroes from the industrial city of Johnstown, Pa., in 1923.

Negro Migrations and the American Proletariat.

1. Racial Prejudice.

Considered from the economic standpoint the Negro problem is a part of the general problem of the unskilled worker in the United States. Except for those working on the cotton plantations in the South, a large number of Negroes work in the steel industry, in the coal mines, in the packing houses, in tobacco and cigar factories. The unionization of the Negroes is made extraordinarily difficult by the artificially nourished hatred of the white worker for his colored fellow-worker. The bourgeoisie is very eager to stimulate racial prejudice.

2. The Trade Union Bureaucracy and the Organization of the Negro.

The trade union bureaucracy has been consistently refusing to accept the Negro into the trade unions. We can cite the attitude and practices of the railroad workers, locomotive enginemen and firemen, the boilermakers and other trade unions.

The American Federation of Labor has concerned itself with the organization of the Negroes only on paper. It is true that there was established in 1920 a special commission for this purpose. But it did nothing. At the congress of the A. F. of L. in 1923 the Executive Council reported that it was impossible to prevail upon the railroad workers and the boilermakers to change their statutes and accept Negroes into their organization. This, however, was only a gesture, since in fact nothing was undertaken to exercise any pressure upon these unions. Because of the efforts of the American Negro Labor Congress, it is said that the Executive Council of the American Federation of Labor has put on four organizers ostensibly for special work among the Negroes.

The harmfulness of these tactics of the trade union bureaucracy is shown with special clarity in the following occurrence in the steel industry, in which at present, many Negroes are employed. From this it is clearly seen how the bosses play the reactionary leaders against the Negro workers in order to prejudice these workers against all the activities of the trade unions in the steel industry. The Negro organ, “The Crisis,” made public in November, 1923, a circular distributed by the Indiana Foundry Company of Muncie among the colored workers who at that time were brought in as strike-breakers. We quote from this circular which had very serious consequences for the strikers:

“Our factory works on the open shop principle. Most of our puddlers, who are colored, have just been trained by us. The union is not in agreement with this and wants to force us to submit to its will. In our city there are four factories in which only members of the union may work and three which are open to all workers. Our factory is the only one in which the Negroes can rise to be skilled workers. Now the union demands that all colored workers who are employed as puddlers should be replaced by whites and that these must submit to the union’s statutes.”

The trade union bureaucrats therefore make i possible for the capitalists to split the proletarian ranks and in the above case were responsible fo the capitalists being able to beat the white as well as the black workers.

3. The Possibility of Organizing the Negro.

Unquestionably, the racial prejudice of the workers makes it much harder to organize the Ne gro proletariat. It must further be added that the Negroes on the cotton plantations of the South were working and living under an almost patriarchal system in relation to their masters. This naturally still tends to influence their minds.

Yet the Negroes have many times demonstrated their organizibility. In 1913 the well-known petty-bourgeois Negro leader, Booker T. Washington, attempted to determine to what extent it was possible to organize the Negro. Out of the 51 questionnaires he sent out for this purpose, only 2 were received with the answer that it was impossible to make the Negroes good members of a labor organization. Moreover, there are already in the United States several mixed unions that include in their ranks white as well as Negro workers. Outside of that, there are 400 independent trade unions of Negroes. Then, there are hundreds of thousands of Negroes who are members of mass organizations of colored workers.

4. Necessity for Unity Between Negro and White Workers.

The rapidly advancing concentration of the Negro proletariat, the increasing political significance of the Negro workers, the efforts of the bourgeoisie to stimulate the racial antagonism between the Negro and the white workers, and finally the growing racial consciousness of the Negro—all of these demand that the workers of the United States und their organizations should not allow racial prejudice to dominate in the least but should adhere only to the class principle. If the white workers follow any other tactics and permit their exploiters to split the proletariat thru racial hatred and prejudice then they will deliver themselves body and soul to their deadly enemies.

5. What Must the American Workers Do?

A solution of the Negro problem in the United States is offered only in the program of the Workers (Communist) Party. The American proletariat must at every opportunity support the Negro in his struggle against the exploiters and oppressors of all the workers—white and black. The American Negro Labor Congress is a step in the right direction for the development of a movement to unify all workers regardless of color against the bourgeoisie.

The American working class must fight for the social, political and economic equality of the Negro.

The representatives of the working class must do everything to remove the obstacles which many trade unions place in the way of the acceptance of the Negroes becoming members. Where this is not possible at the present moment, it is not out of order to form temporarily organizations of Negroes, the chief task of which must be, under all circumstances, to demand unification of the American proletariat regardless of race or nationality against the exploiters, against the bourgeoisie as a whole.

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1926/v5n04-feb-1926-1B-WM.pdf