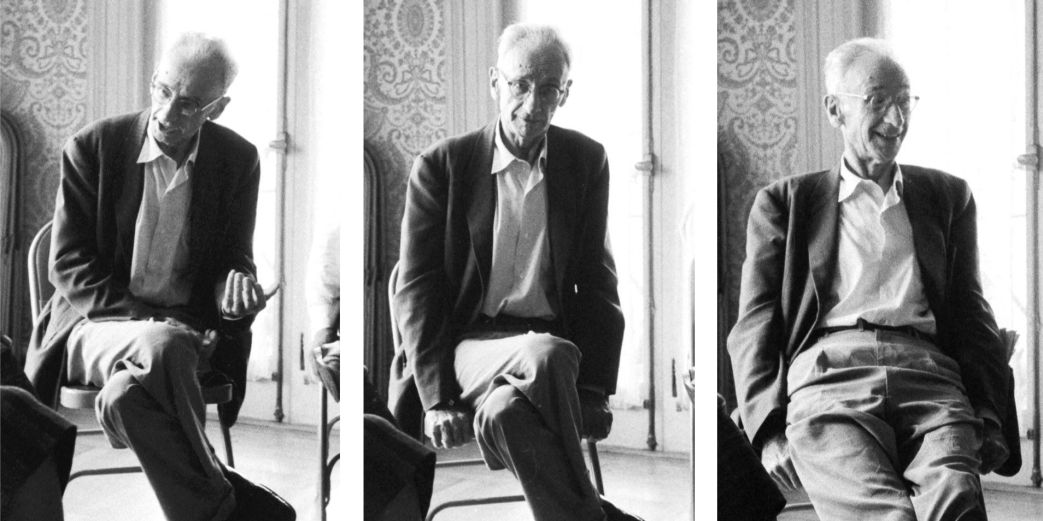

For A.J. Muste, here Dean of the Brookwood Workers’ College and Teachers’ Union delegate to the New York Central Trades and Labor Council, workers’ education was a central focus of his life’s activity. Here, here offers an early explanation of its importance.

‘Workers’ Education: What’s It All About?’ by A.J. Muste from Labor Age. Vol. 13 No. 4. April, 1924.

WORKERS’ education in the proper sense of the term applies to enterprises under the control of workers’ organizations (trade unions primarily), having as their fundamental aim to help the members and officers of these organizations to render more efficient and intelligent service to their organizations. This is a blunt statement with which perhaps some will not agree. What does it mean and how may it be justified?

Every group or class in society carries on some sort of educational work for those who are or may become its members. Such education always has two chief aims. It seeks to impart a knowledge of a certain procedure, of ways of doing things that are of importance to the organization. On the other hand, it also seeks to impart the general aims, ideals and spirit of the group, in order that members may be inspired with loyalty to it.

Thus the fraternal order teaches candidates for membership the rules of the order, grips, passwords, proper behavior at meetings. But in addition it brings before them the great ideas and ideals of the order, in order to inspire enthusiastic loyalty. Thus the church teaches children or prospective members proper procedure in connection with church services and ceremonies. But it also undertakes in various ways to give them an understanding of the doctrines, the philosophy, the fundamental spiritual aims of the church in order to arouse loyalty.

It is so with every kind of educational work. A man goes to law school and learns how to try cases. He also acquires a lawyer’s point of view, which affects him in all the relations of life. He goes to engineering school and learns. how to build bridges but also gets the engineering slant on everything. He goes to Harvard and learns something about physics or chemistry. He also comes out a “Harvard” man.

Ever Since Trade Unionism Began

There has been workers’ education ever since there have been trade unions. It is a great mistake to suppose that workers’ education is something that dropped out of the sky or was conceived by a benevolently disposed professor three or four years ago. By means of meetings, pamphlets and official journals, the trade unions have always imparted education to actual or prospective members. In this way has the union informed them, on the one hand, about shop rules, methods of conducting the organization and other such points of procedure, and on the other hand, inspired them with loyalty to the great aims and ideals of the movement.

Workers’ education is more elaborate and complex today, simply because the tasks confronting the unions are more elaborate and complex. The unions are therefore shaping a more adequate educational instrument to meet the needs of the new day. But the aim of workers’ education is not essentially changed. The primary question to be asked by every enterprise that wears the name is still: “Here are the American trade unions with their increasingly complex problems, tasks, difficulties—with wages and hours to be gained, standards of living to be protected, open shop campaigns and company union drives to be resisted. Here, on the other hand, are the members and officers of these unions. Now, what can we as a workers’ education enterprise do to help fit these members and officers intelligently and efficiently to meet these day-to-day problems and tasks?”

If we keep clearly in mind that the chief aim of any labor class or college is to aid trade unionists (insofar as education may be able to do so) to fight the unions’ daily battle, it will be possible for us to answer many practical questions that face the workers’ education movement.

Can Columbia Teach Picketing?

There is, for example, the question: “Why should workers’ education not be carried on in collaboration with the extension departments of universities, colleges, or city public school systems, or even perhaps be handed over entirely to such institutions?”

There are many sound reasons, both from an educational and from a labor point of view, why this should not be done. In order to educate a man you have to take him where he is. The trade unionist must be educated in an atmosphere, in surroundings where he is at home. The adult trade unionist is by no means at home in the halls of colleges and universities, even when he finds there no direct hostility to his union.

At least some of the subjects that have to be taught in workers’ classes will not, in the present state of things, be offered in the curriculum of a university extension department. Trade unionists have to be taught how to organize different types of workers, how to combat the open shop campaign, how to picket effectively, how to organize strikes. Is it likely that Columbia or the University of Pennsylvania, or many other institutions that might be named, will put such practical subjects into their curriculum?

Workers’ education must to a great extent develop an educational method of its own. The trade unionists that come to our workers’ classes and colleges have a background. They are emotionally mature. They have had years of experience in the hard school of industry. The problem of teaching them is a very different one from the problem of teaching boys and girls in high schools or colleges. Very crudely, one might say that in the main the boys and girls in the colleges have nothing to say but know how to say it, because of their training in organization of thought and expression in the lower schools. On the other hand, the members of our trade union classes have much to say, a rich experience, but they do not know how to say it. From a teaching standpoint, it will be well for some time to come to let our American workers’ classes develop their own technique and not have imposed upon them the educational methods of our existing institutions, which are in any case being subjected to very severe criticism by competent educators.

Trade Unions Must Hold Control

Most important of all perhaps, the trade unions must keep workers’ education under their own control. They must do this because workers’ education must serve not only to impart a certain technique to the members of classes, but also to make clear to them the fundamental aims and ideals of the labor movement and inspire them with a passionate devotion to these aims and ideals. If people do not come out of workers’ classes with a firmer determination to serve their various unions, then it were better that they were abandoned altogether.

But someone will ask: “If the aim of workers’ education is to be to inspire workers with loyalty to the unions, does that not imply that workers’ education is class-conscious?”? The answer must be very frankly, “Yes.” This does not mean inspiring the individual workers with bitterness toward the individual boss. It does not mean inspiring them with a purpose to gain the interests of manual workers in a narrow sense and to wipe out everybody else. We want to inspire the workers with a consciousness of the position, the interests, the aims and the ideals of their group, precisely because it is upon that group and its faithfulness to its mission that the well-being of the whole community is in the long run dependent.

Does this mean that our method in workers’ classes is to be propagandist? Decidedly Someone recently said: “The capitalists select their facts and present in their schools only those that serve their interests. So the workers will select their facts and present only those that serve their interest.” I am in total disagreement with that sentiment. The workers can afford to select all the facts, to face the whole truth. They want nothing more or less than that from those who undertake to teach them. The Labor Movement is the one great modern movement that can afford to be quite scientific in its attitude, even toward itself.

If we are not to entrust workers’ education, at any rate for the present, to any other control than that of the labor movement, does this mean that we must refrain from making use of the services of college men and women who are sympathetic toward the Labor Movement, as teachers? By no means. Control of the movement as a whole being provided for, we must avail ourselves of the best training in various directions that we can make helpful to our enterprise.

Nevertheless, what we have been saying surely implies that we must also bear in mind the importance of developing, so far as possible, young men and women of the labor movement capable of organizing workers’ education enterprises and teaching workers’ classes. The teacher of a workers’ class must not only know something about something, but must know the psychology, the condition of his students. In many cases what the worker who has become a teacher lacks in professional training, he can make up by his knowledge of the psychology of the workers and of the movement.

“Culture” Not Workers’ Chief Need

We need to be careful, however, to maintain the highest standards of teaching, whether our teachers be drawn from the staffs of colleges and universities or eventually from the trade unions themselves.

Perhaps some will complain that workers’ education, as we have defined it, is utilitarian and narrow. Do we not wish to impart “culture” to the worker; to make his life broad and rich; to put him into touch with all the treasures of literature, art and thought?

“Culture” certainly is not to be despised. But the worker is not suffering primarily from the fact that he cannot read Greek, or does not understand Browning, or appreciate the lines of the Venus de Milo. He is suffering primarily from the fact that he does not understand his own position in society as a worker and as a member of the labor movement. Consequently he does not know how adequately to fill that position. That is the basic need which workers’ education must help supply.

The most truly cultured man is the man who knows his position in his social group and knows how to fill it. Once that is taken care of, the worker can then avail himself of the treasures of art and thought. But if this central need is neglected, then culture becomes a mere “frill” or a dangerous substitute for what he really needs.

In other words, practically anything may find a place in the curricula of our labor colleges if the workers ask for it. Provided that we are all the time perfectly clear as to what we are really trying to get at. All this is very far from implying a contempt for culture or a narrow conception of the aim of workers’ education. There is no danger that a man who is a good trade unionist in our modern complex society, with its complex demands upon the labor movement, will be narrow. What we are doing is insisting that workers’ education shall work from the center and not nibble away at the circumference.

How About the “Revolution?”

On the other hand, someone will probably exclaim: “But workers’ education must be revolutionary. It must teach the worker how to overthrow capitalism and it must develop a proletarian culture.” Whatever may be the value of such a statement in general, it does not give us very much help in meeting the practical problems of workers’ education at this moment.

It is to be feared that the people who employ these expressions very often picture the situation in this way: They begin with their vision of Utopia, of an ideal social order off in the distance. Just on this side of their Utopia, they see a dead line sharply cutting off the present state of things from Utopia. That dead line is the revolution. Far, far behind in the dim distance is the trade union movement. Workers’ education is to be the Messiah, the giant that is to drag the reluctant trade union movement the long distance from where it is now—over the dead line of the revolution into Utopia! The result of such an approach, it seems to me, is bound to be misleading. Let workers’ education take its place not outside the trade union movement, but in it. Not as an instrument fashioned by somebody else, that is to do something to the movement, but as an instrument being fashioned by the movement itself. Here we stand where the movement stands; with wages to be raised, hours to be lowered, with intolerable housing conditions to be remedied, with strikes and lockouts to be fought, with injunctions and Supreme Court decisions to contend against, with the open shop drive to combat, with increasing responsibilities for the control of industry. The workers’ education movement will have a practical, yet most glorious place, to fill—if as an instrument being created by the movement, it helps to equip the officers and members of the movement to meet those problems and tasks. If it consistently and honestly maintains this point of view about itself, it will never be reactionary. It will never dull the edge of the workers’ aggressiveness. It will not impart to them a false “refinement” that makes them too good for practical service in the movement. It will inevitably grow as the American Labor Movement itself inevitably grows.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v13n04-apr-1924-LA.pdf