‘Saint Simon and the Saint-Simonians’ by Max Beer from Social Struggles and Thought. Translated by H.J. Stennings. Small, Maynard, and Company Publishers, Boston. 1925.

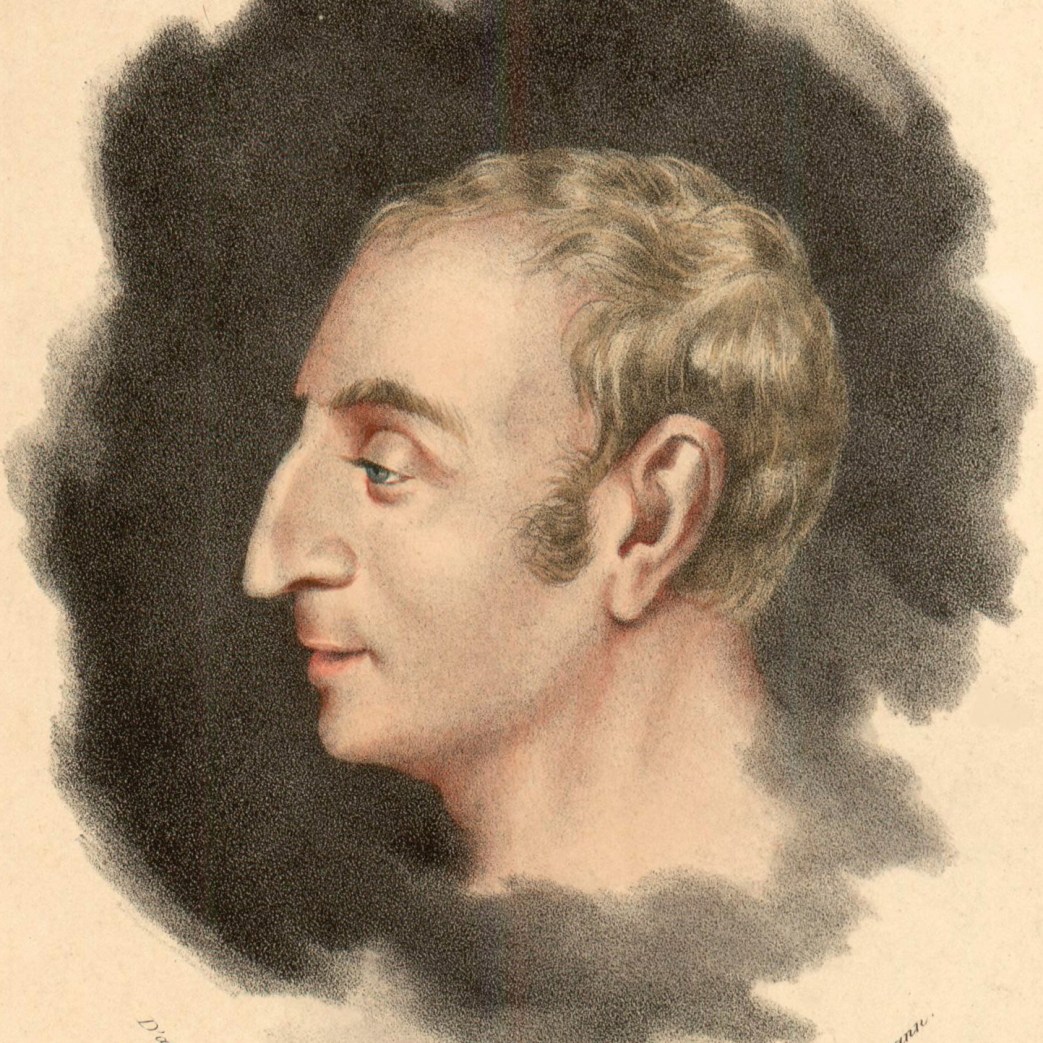

Saint Simon.

It is necessary to distinguish between Saint Simon and the Saint-Simonians as strictly as between Kant and the Neo-Kantians. Saint Simon was as little a Socialist as Kant; both rather belonged to the Liberal school of thought; Kant was a philosophic Liberal, Saint-Simon an economic Liberal; both regarded religion as the doctrine of practical ethics.

It was only the younger generation of Saint Simon’s disciples, who were familiar with the associative theory of Fourier, the English labour struggles and social doctrines (1810—1826) and with Buonarroti’s socialist ideas, who, after 1829, commenced—four years after the death of their master—to impart a social-reformist tendency to the ideas bequeathed to them, just as the Neo-Kantians, who are acquainted with modern socialism, endeavour to establish the closest connection between their master and Marxism.

Count Henri de Saint-Simon was a scion of a family belonging to the higher nobility of France; he was related to the famous writer of memoirs, the Due de Saint-Simon (under Louis XIV) and traced his pedigree back to Charles the Great. He was educated according to his class, for Court and military circles. As a young officer he fought by the side of Lafayette in the American War of Independence against England, and there learned to admire the purely middle-class nature of the United States. He had already drawn up plans for the construction of the Panama Canal, as he was keenly interested in all problems relating to commercial and industrial activity. On returning to France, he took no part in the Revolution, but utilized the economic opportunities to buy and sell confiscated properties, thus acquiring much money (140,000 francs), which enabled him to fill up the gaps in his knowledge and indulge in all the enjoyments which life could offer him. The money was soon dissipated by the aristocratic-intellectual mode of living, and then he lived sparingly and often in great need, until the Jewish banker, Rodrigues, and his friends afforded him the means of passing the evening of his days free from care. In the years 1802—1825 he developed a lively journalistic activity. His ideas were born of middle class industrial interests and his personal humanitarian inclinations. A glance at the conditions of that time shows this distinctly.

The middle class, which had grown rich during the Revolution and the wars following in its wake, acquiesced in the Napoleonic despotism so long as victory crowned it with a halo of glory. After the catastrophes of Moscow and Leipzig (1812 and 1813), the middle class went into opposition, and when Napoleon returned from Elba to Paris he was confronted with a strong constitutional movement, to which he was obliged to make concessions.

After his final defeat (1815), the Bourbons (Louis XVIII, 1814—1824, and Charles X, 1824—1830) returned to power. They ignored all the lessons of the Revolution, and restored the nobles and clergy to their old position, whereupon the middle class became rebellious. Economically it was much stronger than its predecessor of 1789, as technology and industry had made considerable progress in the meantime. While their representatives more than ever felt that they wielded the real power in the State, the Bourbons deprived them of all political influence. A rebellious bourgeoisie always seeks the assistance of the lower classes and regards itself as the representative of the people against personal monarchy and reaction.

The intellectual product of these conditions was Saint-Simon (1760—1825) and even more the Saint-Simonians, for the latter came into prominence on the eve of the July Revolution, when middle-class circles found themselves in sharp opposition to the Bourbons, whereas Saint-Simon was only an eye-witness of the beginnings of this rebellion and laboured for a reconciliation between the monarchy and the bourgeoisie.

The essence of Saint-Simon’s doctrines consists in the proposition that the chief task of society should be to promote the production of wealth, that consequently the industrialists (the manufacturers, technicians, farmers, artisans, bankers, merchants) form a more important factor in society than the nobility and the clergy, and that middle-class talent should undertake the administration of the country. “It is not the political constitution, but the right of property that has the greater influence upon the wellbeing of society. The claim to property should be based on the growth of wealth and the freedom of industry. The law that establishes property is the most important of all: this it is that serves as basis of the social structure. The law that defines the division of powers and regulates their exercise (i.e., the Constitution) is only a secondary law.” (Saint-Simon, “Euvres,” edited by Rodrigues, Paris, 1841, first part, pp. 248, 257, 259, 267.) Saint-Simon sometimes distinguishes between the right and the law of property. The former he regards as progressive: “as the human intellect progresses, the law of property, as once established, may not be perpetuated.” (p. 265.) He further contends that the property of the nobility is based on conquest, on force, whereas that of the industrialists (manufacturers, farmers, bankers, merchants, artisans) is the result of their legitimate activity. His conception of property is a defence of middle class and a condemnation of aristocratic property and of the political pretensions of courtiers, and highly-placed State and ecclesiastical dignitaries. A popular summary of these ideas is contained in the parable which Saint-Simon published in 1819, for which he was prosecuted but declared to be not guilty by the jury. In this parable he compares the eventual loss of the fifty first physicists, chemists, technicians, industrialists, shippers, merchants and artisans with that of fifty princes, courtiers, ministers and higher clergy. The loss of the former would be irreplaceable, whilst the fifty vacant places of the latter would be easy to fill. Saint-Simon therefore advised the Bourbon King Louis XVIII to ally himself with the industrialists and become a citizen king. The French bourgeoisie also sighed for a citizen king, who was granted them in 1830—after the fall of the Bourbons—in the person of King Louis Philippe (1830—1848).

Saint-Simon also made some incursions into philosophical history, and attempted to exhibit the past in the light of his conceptions. We shall deal with them in connection with Saint Simonism in the following chapter. Meanwhile it is to be emphasized that Saint-Simon’s economic ideas were purely middle-class in their character, and at first his attitude to the workers was also a middle-class attitude. In his first work, “Lettres d’un habitant de Geneve” (1802), he divided society into three classes: (1) into liberals (scholars, artists, as well as all persons having progressive ideas);

(2) into possessors, who desire no innovations;

(3) into those persons who rally round the word “equality.” To the workers who strive for equality he declared: “The possessors have acquired their power over the nonpossessors, not by virtue of their property but in consequence of their intellectual superiority.” (“CEuvres,” second part, pp. 24, 27, 40.) “Look at what happened in France,” he says to the workers, “when your comrades ruled there: they brought about starvation.” (p. 40.) Saint-Simon was thinking of the period of the Convention (1792-94); he did not know that it was not the workers at all who ruled then; he was also unaware that the starvation was the work of the opponents of the Jacobins; the jobbers, the forestallers, the profiteers. Saint-Simon regarded the rule of the Convention as “the most complete anarchy.” (p. 136.) “The Convention destroyed Louis XVI, the noble philanthropist, and the monarchy, the fundamental institution of the social organization of France. The Convention created a democratic constitution, which gave the greatest influence to the poorest and most ignorant.” (p. 136.)

It is true that Saint-Simon remained a Liberal, and, therefore, a supporter of the rule of the industrialists, but as an enlightened man he was also a careful observer of the movements among the workers. He noted how the English industrial workers had been revolting against the industrialists since 1810, destroying machines (Luddite movement), and embarking on a struggle for the franchise and factory protection (1816—1818). Moreover, he was himself in want, and possessed a strong moral and religious disposition, which prompted him to pay attention to the social doctrines of Christianity; he knew Lessing’s “Education of the Human Race,” and was influenced by its ideas. After 1819 Saint Simon emphasizes more and more the necessity of assisting the workers. In the “Catechisme des Industriels” he exhorts the employers to look after the workers: “The captains of industry are the born protectors, the natural leaders of the working class. So long as the captains of industry refrain from uniting with the workers, the latter will be seduced by intriguers and radicals into making a revolution and seizing the political power.” (“CEuvres,” first part, p. 221.) The events in England serve as illustrations. In the last years of his life his interest in the well-being of the workers outweighed all other interests; his views upon this subject were expounded in a work published immediately before his death, “Le nouveau christianisme” (1825); the new Christianity shall so regulate the relations between Capital and Labour that “the most rapid improvement possible of the lot of the poorest classes will be effected;” the new Christianity sheds the Catholic and Protestant dogmas and rituals and becomes social ethics, whose chief postulate is that men should behave to each other as brothers. “The new Christianity will consist of parts which in the main coincide with those that are peculiar to the various heretical sects of Europe and America. Like primitive Christianity in former days, the new Christianity will be supported and promoted by the force of morals and public opinion.” Saint-Simon then states that at first he addressed his teaching to the rich, in order to win their support for these doctrines, at the same time making it clear to them that his doctrines “were not opposed to their interests, because apparently an improvement in the position of the poor is only possible through means which cause a decrease in the pleasures of life of the wealthy classes. I have to make the artists, the scholars, and the great employers understand that their interests are essentially identical with those of the masses of the people, that they, on the one hand, belong to the working class, and, on the other hand, are its natural leaders, and that the applause of the people for the services rendered it is the only worthy recompense for their glorious influence.” He even appealed to the Holy Alliance and the rest of the kings and princes: “Unite in the name of Christianity and perform the duties which it imposes upon the mighty; know that it commands them to dedicate all their strength to the most rapid elevation possible of the social fortunes of the poor.”

After the announcement of this “new” gospel Saint-Simon died. Summarizing, it may be said: Saint-Simon was neither a Socialist nor a Democrat, but a Liberal with a strong ethical bias, who was able to give consistent expression to his Liberal and ethical theories only because of his intellectuality and his aloofness from the pursuit of money. This applies particularly to his doctrine of property, which—in view of the rise of the working class and the beginning of the proletarian class struggle—could bear an interpretation unfavourable to middle-class property. And this interpretation of the doctrines of their master was effected by the Saint-Simonians.

The Saint-Simonians

The small number of supporters who adhered to Saint-Simon’s doctrines belonged almost exclusively to the cultivated and prosperous section of the population. After 1827 the elections to the Chamber more and more favoured the opposition, but ever since 1821 the intellectual youth of Paris had formed secret associations to overthrow the Bourbons, to establish the sovereignty of the nation, and “to emancipate the people.” They entered into relations with the Italian Carbonari, learned their conspiratorial methods, studied the French Revolution and English social conditions and theories, and were receptive to all kinds of new ideas, as understood by revolutionary youth who were obliged to organize in secret. Among these young people were Saint-Amand Bazard (1791—1832), a logical, clear-thinking mind, and P.B.J. Buchez (1796—1865), who was later to devote himself to propaganda in favour of co-operative production (with State aid). Bazard became a Saint-Simonian in 1825; he read Buonarroti in 1829, and in the following year he lectured on the doctrines of the master at Saint-Simonian meetings. His collaborator was B.P. Enfantin (1796—1864), manager of financial institutions and later a railway director, a man who combined high imagination and enthusiasm with great energy and acuteness. With them were active the brothers Pereire, who were later the founders of great financial institutions, and then Ferdinand Lesseps, the subsequent constructor of the Suez Canal and director of the preliminary work of the Panama Canal. It may be seen how the real essence of Saint-Simon’s doctrines: industrial-commercial Liberalism, eventually worked out; meanwhile, however, the social aspect occupied the foreground and the Saint-Simonians were regarded as Socialists. The collected works of Saint Simon and Enfantin (CEuvres de Saint-Simon et d’Enfantin) contain the brilliant “Exposition de la doctrine Saint-Simonienne” (Exposition of the Saint-Simonian teaching), which Bazard gave in his lectures (1829 — 1830). He took certain of the ideas of Saint Simon, developed them with the aid of the results of his own studies and experiences, and blended them into a homogeneous system. The basic features of this system are as follows:

Saint-Simon taught that in the history of mankind organic and critical periods alternate. The first is characterized by unity of thought and belief, a certain community of social interests; such periods were: Greece, up till the fifth century B.C., where polytheism held undisputed sway; further in the Middle Ages up till the appearance of Luther, where the Catholic Church formed the spiritual unity. The organic periods are followed by the critical, where the unity of thought disintegrates and social dissonances appear; as in Greece after the fifth century B.C., where a variety of philosophical systems arose. In the Middle Ages the critical period commenced with the Reformation, which was accompanied by various systems of thought and revolutions, to be followed by an organic period. To inaugurate this period is the mission of Saint Simon, who expounded it in the “New Christianity.” It will close the critical period ushered in by Luther.

Following out this train of thought, Bazard declares that the alternating organic and critical periods are characterized by the principle of association and that of antagonism respectively. The antagonisms or conflicts, however, are of a temporary and secondary nature, whilst the chief endeavour of mankind and the chief law of history is association. The antagonisms and struggles between families and towns were fought out with the object of welding the nation together under the empire of one faith, of a spiritual unity. Mankind is now striving to achieve the great, universal, organic union in which love, knowledge and wealth will increase.

The antagonisms and conflicts are always caused by the domination of physical force, which leads to the exploitation of man by man. But the effect of this force is always weakening; and this weakening process is revealed in the progress which has transformed the slave into the worker of to-day. The graduated stages are: slavery, servitude, wage labour. Here is distinctly shown the decrease in the exploitation of man by man.

While the person of the slave belonged to his master, the serf was possessed of some liberties, and the modern worker is politically free; what the latter still lacks is freedom from economic dependence. This progress is also manifested in the growth of association, but this growth is still hindered by clinging to the traditional law of property, which enables the proprietor to live without working and to rule other men. At least it is said “that property is the basis of the entire political order. We Saint-Simonians are generally of this opinion, but property is a social fact which is subject to the law of progress. Property may therefore be understood, defined and regulated at various times in various ways.” (Vol. 41, p. 231.) Heinrich Heine, who, in the thirties of the last century, kept the German public informed about this movement in his Paris correspondence to the “Augsburg Allgemeine Zeitung,” observed ironically: “The Saint Simonians do not want to abolish property, but to define it out of existence.”

However, the Saint-Simonians advocated the abolition of the right of inheritance. “The property of deceased persons should fall to the State, which will have become an association of active workers. The whole nation should inherit and not the family concerned. The privileges of birth, which, moreover, have suffered so many relaxations, should be completely abolished.” (p. 243.) Why should anybody attain to wealth merely because he is the son of his father or the relative of another person? The sole right to property is the capacity to produce it. In the associated State, in the association of active workers, everybody will occupy a position according to his capabilities, and will be paid according to his deeds. The State will be transformed into an economic administration, at the head of which will be the best administrative talent available; just as to-day we have military academies to educate capable army officers, so in the associated State there will be schools and academies for industrial leaders. The task of these leaders will consist in managing the national household, classifying the workers according to their capabilities, allocating them to the most suitable positions, and rewarding them according to their services. The economic process will be regulated, not by a democracy but by a hierarchically-organized management. Only in this way will it be possible to abolish idleness, overwork, poverty, exploitation of man by man, and the vestiges of slavery, and to establish the new organic period, the epoch of social harmony.

The modern worker, who has become politically free, must also be made industrially free. But this need not be effected by forcible revolution. “The teaching of Saint-Simon aims at no overthrow, at no revolution; it aims at a transformation, at evolution— it brings the world a new education, an ultimate rebirth.” (p. 279.) Hitherto great changes have been marked by a forcible and catastrophic character, because men were not acquainted with the laws of progress. It was ignorance which turned evolution into revolution. Now mankind is conscious that it is progressing, and already it perceives the law of social crises; consequently it is easy to prepare the transformation and avoid being surprised by force. “The changes in the social organization which we announce—the notion that the present system of property will have to yield place to quite different property institutions—will be effected neither suddenly nor forcibly, but by means of a peaceable and gradual transition.” (p. 281.) In the Saint Simonian associated State the highest social stage will be occupied by religion (by the preachers of the New Christianity); the second stage by the natural scientists; the third by the industrialists. Moral and religious enthusiasm, clear-sighted, disciplined reason, and efficient industrial technique will redeem mankind. (Vol. 42, p. 388 et seq.)

These lectures of Bazard aroused much interest, and were eminently fitted to attract intellectuals, artists, and benevolent Liberals.

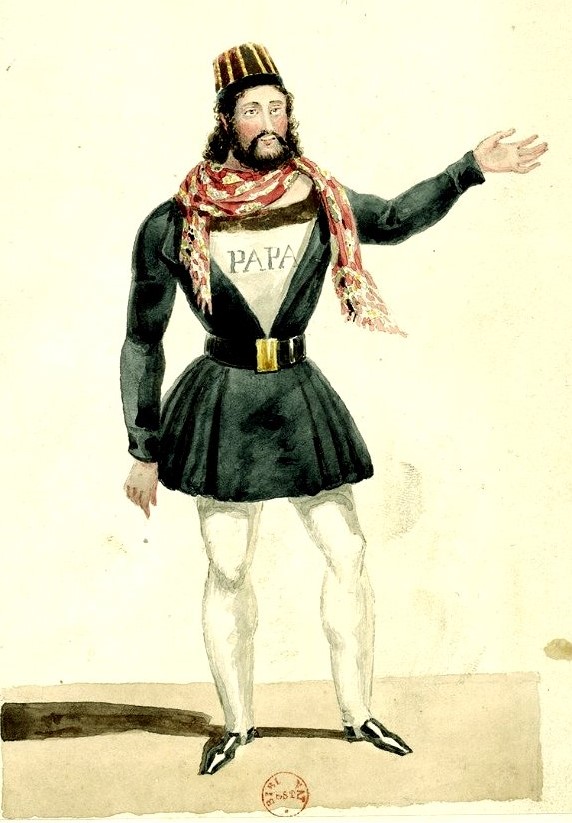

However, division soon broke out among the Saint-Simonians, which rendered impossible any further successful propaganda. Enfantin, in violent antagonism to Bazard and Rodrigues, came under the influence of the Fourierist ideas concerning the emancipation of women, and attempted to graft the principle of free love on to Saint-Simonism. To this most of the members objected. Enfantin withdrew with a number of his followers to Menilmontant, where he lived for some time as a social father with his community. Saint Simonism as a movement became impossible, but it bequeathed to the social-revolutionary movement of 1830—1848 a wealth of sociological and economic ideas which continued to operate for a long time.

Social Struggles and Thought by Max Beer. Translated by H.J. Stennings. Small, Maynard, and Company Publishers, Boston. 1925.

Contents: I) THE ECONOMIC REVOLUTION IN ENGLAND, Ascendancy of the Commercial and Trading Class, Mechanical Inventions and the Factory System, Smith Bentham and Ricardo, II) ENGLISH SOCIAL CRITICS DURING THE FIRST PHASE OF THE ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION, Robert Wallace: Communism and Over population, Spence and Land Reform, Godwin and Anarchist Communism, Charles Hall: Expounder of the Class Struggle, III) THE ATTEMPTED ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION IN FRANCE, From Tutelage to Freedom, The Physiocrats: Economic Freedom: Laissez faire, laissez Aller, IV) THE FRENCH REVOLUTION, The Classes and the Constitutional Conflict, The Revolutionary Dictatorship, The Constitution of 1793 and Social Criticism, Lange and Dolivier, V) THE CONSPIRACY OF BABEUF AND HIS COMRADES, Causes Objects, Filippo Buonarroti and the Revolutionary Dictatorship, The Upshot of the Conspiracy, VI) REACTION UPON GERMANY, Economic Revival and Political Oppression, Wieland and Heinse on Communism, Heretical Social and Religious Tendencies: Weishaupt (The Illuminati), Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Friedrich Christoph Oetinger, Fichte and his Social Policy, VII) THE FRANCE OF NAPOLEON AND THE RESTORATION, War Imperial Policy and Commercial Speculation, Charles Fourier, Saint- Simon, The Saint- Simonians, VIII) THE BEGINNINGS ENGLISH OF THE LABOUR MOVEMENT (1792–1824), The Influence of the French Revolution, The Luddites, Storm and Stress, Robert Owen, Combe Gray Thompson Morgan Bray, Individualistic Social Reformers, IX) ENGLAND’S FIRST SOCIAL REVOLUTIONARY MOVE MENT (1825—1855), 1st Stage: Alliance Between Working and Middle Classes for the Franchise (1825-1832), 2nd Stage: Anti-Parliamentarism and Syndicalism (1832—1835), 3rd Stage: Chartism (1836–1855), X) FRANCE (1830-1848), The Citizen Monarchy, The Class Division into Bourgeoisie and People, Secret Conspiracies and Revolts, August Blanqui, Socialists and Social Reformers: Pecqueur Proudhon Cabet Leroux Blanc, February Revolution of 1848, INDEX. 232 pages.

PDF of original book: https://books.google.com/books/download/Social_Struggles_and_Thought.pdf?id=BUkGAAAAMAAJ&output=pdf