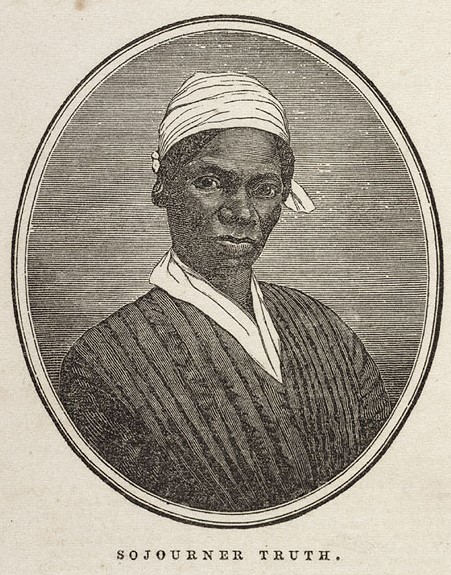

‘Sojourner Truth: An Unsung Heroine’ by Otto Hall from Working Woman. Vol. 6 No. 6. June, 1935.

IN the struggles of the Negro slaves for their freedom, the Negro women played an important role. They fought side by side with their men in many of the slave rebellions, were active in in the Abolitionists’ movement, and were also active workers in the “Underground Railroad.” One of the most famous Negro woman fighters against slavery was Sojourner Truth. It is not known when this remarkable woman was born, as it was not customary to keep a record of such “trivial events” as the birth of slave children. This much is known, however, that she was born at a place called Hurley, Ulster County, New York, some time during the last quarter of the 18th century. Her parents were the slaves of Colonel Ardinburgh and were sold when she was quite young. Her name originally was Isabella, but she called herself Sojourner Truth.

Carried Scars to Death

At nine years of age, her master sold her to one John Weely of Ulster, New York. Her first master Dutch, and at the time of her sale, she did not know a single word of English. She received many cruel beatings because, not understanding her mistress’ orders, she was constantly making mistakes. For failure to understand an order, she was taken to the barn one Sunday morning, stripped to the waist, and beaten till the blood ran down her back. She carried scars from this beating to her dying day. She was then only about ten years old. She was sold several times afterwards until she became the slave of a Mr. Dumont, who treated her more kindly. She had grown to be a gaunt, rawboned woman, a pure African type, and was said to possess more strength than most men. She was the mother of 13 children, all of whom were taken away from her and sold before they were grown. Her owners forced her to plow the fields and in other ways do the work of a man.

Like most slaves of her time she had been taught to be very religious. The Bible had been read to her and she had managed to utilize only those parts that seemed to justify her activities and to cast aside the rest.

She had never learned to read and write but had a keen mind, a good memory, plenty of native wit, and a very sharp tongue. She was an orator of no mean ability, being able to electrify her audiences with a few forceful sentences. She was said to have been able to remember things that she had been told many years before.

Fought For Freedom

Never satisfied with her condition of slavery, she finally ran away from her master and refused to come back. When he came after her she told him that she knew that, according to the Manumission law (passed by the New York Legislature in 1811) she was entitled to her freedom, having served the required time. This was in 1827. The law had decreed that all slaves living in New York who had slaves reached the age of 40 were to be liberated at once; the others in 1828, and the children upon reaching their majority. Her master had promised her freedom for faithful service before that time, but she was so valuable that when the time came for him grant her freedom, he attempted to put it off. She, however, would not stand for this and left. A kindly Quaker family gave her refuge and, refusing to surrender her to her master, finally settled with him by paying him $20 for her freedom, a sum of money to which he was not entitled.

Founder of the Underground

After having secured her freedom, she devoted her time to the cause of emancipation. She was one of the founders of the “Underground Railway” system. It was a very ingenious system. Agents were posted at strategic points in many of the larger Southern cities, people who were devoted to the cause of Abolition, but who would be the last ones to be suspected of carrying on such work.

Slaves who wanted to escape were told by others where these agents could be reached. A slave who could get from the plantation to the first “station” usually was safe. Various clever methods were used in getting the slaves from station to station. They were usually shipped to others connected with the movement, concealed in boxes or barrels with hidden airholes and sufficient provisions for the journey. These boxes were very often shipped long distances, and on many occasions the slaves endured untold hardships and died on the way. Some were disguised as body servants and personally conducted the agent from place to place, until they finally reached their goal. It is known that thousands of slaves made their escape through the “Underground Railroad.”

A cabin situated in an isolated spot a few miles out from town, and thought by the people of the community to be haunted, was used as one of the stations. Sojourner was known to have kept lonely vigil, night after night, with a shotgun over her shoulder, at one of these stations.

Labored Without Pause

She made the acquaintance of Frederick Douglass some years later and became one of his admirers and life-long friend. Her energy was tireless. As an active Abolitionist, she traveled over a considerable portion of the country, lecturing against slavery.

Just before the Civil War, she held a number of meetings in Ohio and hit the local apologists for slavery (known as copper-heads) sledge hammer blows. At one of these meetings a small-town wise guy interrupted her speech and said, “Old woman, do you think that your anti-slavery talk does any good? Why, I don’t care any more for your talk than I do for the bite of a flea.” “Perhaps not,” she answered, “but the Lord willing, I’ll keep you keep you scratching!”

She met an old friend one day who asked her what business she was following. She quickly answered, “Years ago, when I lived in the city of New York, my occupation was scouring brass door knobs; but now I go about scouring ‘copper heads’.”

At the Women’s Rights Convention

She was known not only as an Abolitionist, but also as one of the pioneer fighters for women’s rights. She often spoke at their meetings. At that time any advocate of women’s suffrage was looked upon generally as an extreme radical, and was subjected to as much abuse and vilification as were the Abolitionists. She was a delegate to the first Women’s Rights Convention ever held in this country, the only Negro woman there.

Many opponents of equal suffrage attended this convention, and their continual heckling threatened to throw the convention into confusion. But Sojourner saved the day. She put the hecklers to rout. One of them raised the objection “That according to the Bible, ever since women had been on earth from the time of Mother Eve, they have meddled in men’s affairs and have by so doing turned the world upside down.”

Sojourner came right back at him. She rolled up her sleeves, showing her muscular arms, and declared that she was able to do as much work as any man, and had plowed fields night and day, had brought numerous children into the world, had never had to give way to the strongest man, and wasn’t she a woman?

She Talked Turkey

She stated further, “If the first woman God ever made could turn the world upside down all alone, all of these women, together, ought to be able to turn it back and get it right side up again, and now that they were asking to do it, the men had better step aside and let them.”

A Long, Useful Life

It is believed that she was well over 100 years old when she died at Battle Creek, Michigan, in 1883, but she was active to the last. Just a year or so before her death, a famous preacher of that time remarked, after hearing her speak in Topeka, Kansas, “She was more than a hundred years old, but her voice filled a large auditorium, and she held her audience with ease.”

The Working Woman, ‘A Paper for Working Women, Farm Women, and Working-Class Housewives,’ was first published monthly by the Communist Party USA Central Committee Women’s Department from 1929 to 1935, continuing until 1937. It was the first official English-language paper of a Socialist or Communist Party specifically for women (there had been many independent such papers). At first a newspaper and very much an exponent of ‘Third Period’ politics, it played particular attention to Black women, long invisible in the left press. In addition, the magazine covered home-life, women’s health and women’s history, trade union and unemployment struggles, Party activities, as well poems and short stories. The newspaper became a magazine in 1933, and in late 1935 it was folded into The Woman Today which sought to compete with bourgeois women’s magazines in the Popular Front era. The Woman today published until 1937. During its run editors included Isobel Walker Soule, Elinor Curtis, and Margaret Cowl among others.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/wt/v6n06-jun-1935-Working-Women-R7524-R1-neg.pdf