Manuel Gomez (born Charles Phillips, he took the name Gomez while living in Mexico on the run from World War One draft evasion) with an informative background on the Cristero War that followed the Mexican Revolution.

‘The Catholic Rebellion in Mexico’ by Manuel Gomez from Workers Monthly. Vol. 5 No. 11. September, 1926.

REVOLUTIONS are fought and won, and as a result certain revolutionary conquests are written into law. When the acute revolutionary situation has given way to the peaceful dominance of the new regime, these laws have to be applied. But here it develops that the enemy has been by no means finally disposed of. Out from its temporary hiding places creeps the old regime. Every attempt to apply the new laws is a signal for renewed struggle. The fight then begins all over again on propositions that are officially assumed to ‘have been accepted by the entire population as a matter of course.

A revolution has not really triumphed until the revolutionary gains are established beyond question in the new society. Until then, every one of them is a possible point of focus for reactionary counter-attack.

The Mexican revolution wrote its Magna Charta in the Constitution of 1917. Two of the most typical sections are Articles 27 and 123, both of which were acclaimed thruout Mexico on their adoption as embodying great revolutionary gains. Nevertheless, so complex were the forces that became assimilated to the victorious revolutionary regime, so paralyzing was the dead weight of old class relationships upon the government, and so persistent was the outside opposition, that years passed without any determined effort to put them into effect. Setbacks encountered with regard to one constitutional provision opened the way for resistance to others. Slowly, the reactionary front crystallized again along the whole line. It was—and still is—a weak and wavering front, for the reactionary classes must again be awakened politically before they can be galvanized into activity on a big scale, but it has gained confidence thru the idea that help may come to it from unexpected sources.

The present Catholic rebellion brings to a crisis the entire period of post-revolutionary resistance to the conquests of the revolution. None but a philistine could believe that it is merely a religious struggle, or even a strictly Church struggle.

It is a well known fact that the United States has been a prime factor in obstructing the application of the Mexican constitution from the beginning. Article 27, which more than any other may be said to symbolize the revolutionary aspirations, was the target for incessant pounding by the oil interests, their Wall Street bankers, and their Washington political executive committee.

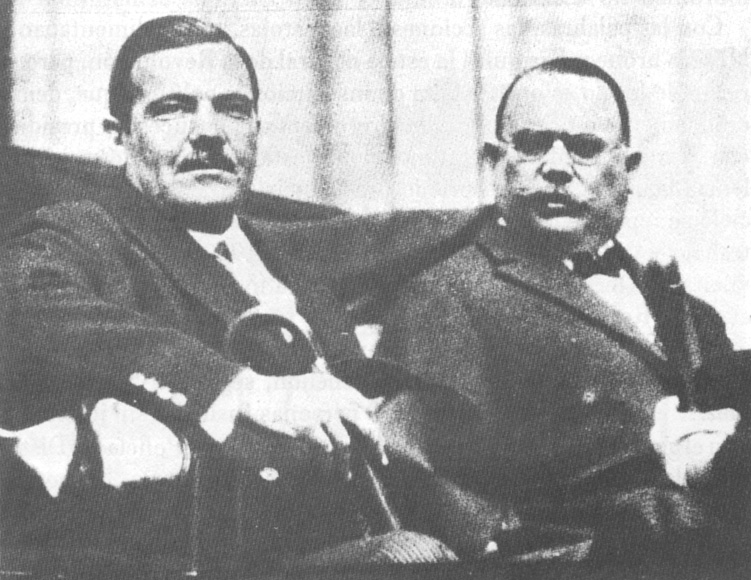

Neither Carranza nor Obregon made any determined effort to apply Article 27 in the face of the U.S. imperialist fury. ‘Calles attempted to confront the storm. His administration presented to the Mexican congress two laws, known as the Alien Land Law and the Petroleum Law. They were passed on January 1st, 1926—nine years after the promulgation of the famous Queretaro constitution. These were enabling laws for the enforcement of Article 27. Diplomatic pressure by the United States government began in October, 1925, even before the oil and land laws were adopted. On October 29th, the U.S. ambassador addressed a series of significant inquiries to the Mexican Foreign Office. Notes from Secretary of State Kellogg followed in impressive succession. Threats from both Wall Street and Washington filled the air. All through the winter and into the spring of this year the offensive continued—until finally during the month of March the Calles government gave way. Calles, who could not present as resolute an opposition to American imperialism as was necessary because of the petty-bourgeois defects of his regime, conceded most of the U.S. demands in a series of administrative regulations for the enforcement of the new laws.

Relations between the United States and Mexican governments are still tense. For American imperialism is by no means satisfied with the national-revolutionary program of Calles. The atmosphere of conflict continues and becomes more threatening from day to day.

Taking comfort from this atmosphere that the native Mexican reactionary elements become bolder. The abortive counter-revolution of Adolfo de la Huerta in 1923-24 was little more than a military tour de force. The present situation in Mexico reveals an attempt to elevate the opposition into a wide-spread, deep-going movement with a common reactionary ideology.

American imperialism is obviously not the only enemy of the revolutionary constitution of 1917, nor even of Article 27. This article, besides striking at foreign monopoly control of Mexico’s oil and other resources, includes the revolutionary agrarian program for the break-up of big landed estates. It also includes most of the constitutional provisions against the power ft the Catholic Church.

Mexican landed aristocrats have banded themselves together in the so-called Sindicato de Agricultores, which maintains armed “white guards” in various parts of the Republic to intimidate the peasants and the local agrarian commissions charged with the carrying out of the land laws. The Sindicato de Agricultores is a closelyknit organization carrying on constant guerrilla warfare against Article-27 of the constitution by all possible means, legal, extra-legal and illegal.

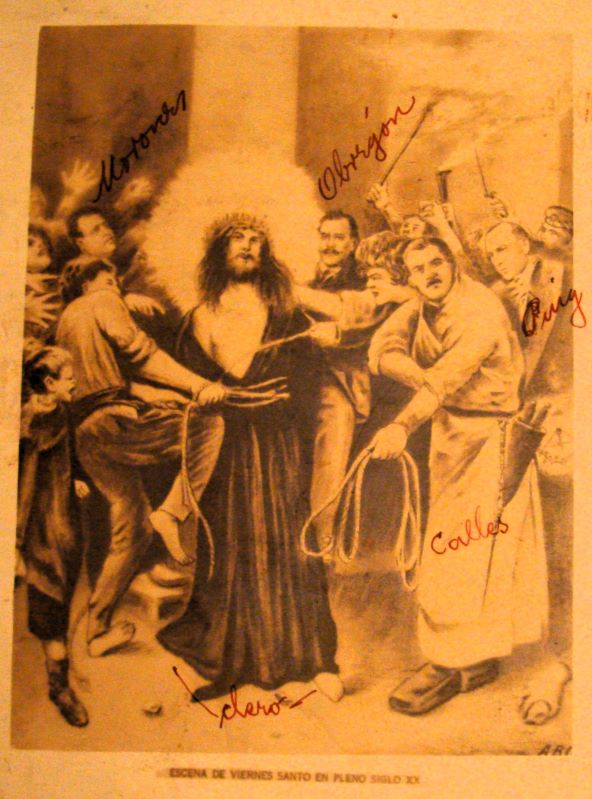

But upon the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico falls naturally the task of uniting and expressing all of the elements of the opposition. The Church with its peculiar religio-political position, its over-powering traditions and its wide-spread ramifications among the masses of the people, is the manifest point of focus of Mexican reaction.

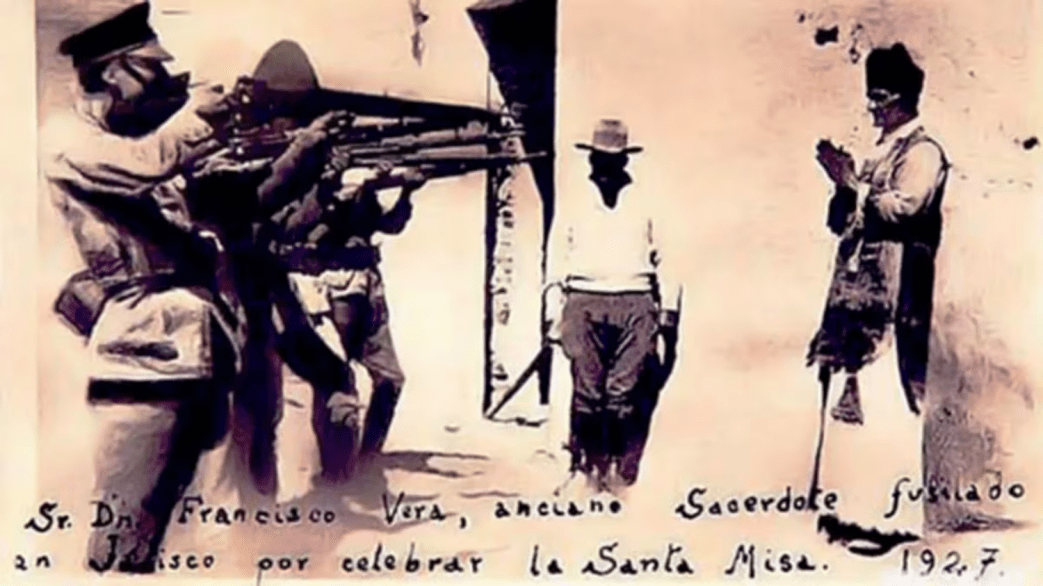

The reactionary quick-step is, therefore, signalized by a concentration of struggle around the anti-clerical provisions of the constitution. Twenty-five thousand priests are on a general strike, refusing to perform any clerical function. An economic boycott, organized by wealthy Catholic laymen with the connivance of Rome, aims to paralyze the life of the country and thus bring the government to its knees. President Calles, petty bourgeois revolutionary-nationalist, is forced to use every governmental and extragovernmental instrument in trying to apply the anticlerical provisions of the Mexican constitution, which had long ago been established by force of arms. The entire nation is aroused. American imperialism peers eagerly over the border, hanging on the outcome. Organized reaction, clerical and otherwise, is once more engaging the forces of the Mexican revolution.

The national revolutionary front is standing firm. If the international situation does not take a more decisive turn, and if President Calles takes the requisite steps, relying more confidently than in the past upon the laboring masses, the Church power may now be finally disposed of.

The Catholic Church was dis-established in Mexico as far back 1857, when the Jaurez pro-capitalist movement, in an early attempt to sweep away semi-feudal incumbrances, launched out against all the bulwarks of the old aristocracy. Jaurez helped to dispossess the peasants of the land, thus laying the basis for new agrarian problems. But he broke up many of the old aristocratic centers of vantage. In the constitution of 1857, and in the Reform Laws Jaurez’s regime initiated what was to be the Mexican Reformation.

Church and state were separated, never again to be united. The Church was forbidden to hold property (this was unconsciously part of the classic pro-capitalist program to free the land from incumbering restrictions). Secular orders, monasteries and convents were suppressed. Education was secularized. The religious oath was abolished, and marriage was declared to be a civil contract.

We have already seen that constitutional provisions are easier enacted than applied. The clergy was the best educated class in Mexico; their parishes possessed a continuous existence, and it was practically impossible for the state to distinguish between gifts to the Church for current expenses and gifts that would render the parish wealthy. When the “cientifico” regime developed under Porfirio Diaz it was natura] that the clergy and the Catholic leaders should have assumed a more important part in public affairs. Gradually many of their lost powers ‘were regained.

The overthrow of Diaz and the further march of the great Mexican revolution of 1910-20 was a final accounting with feudalism.

In its initial stages the revolution appeared as a vaguely conscious pro-capitalist rising against the Diaz dictatorship. Almost simultaneously the Zapata-led movement of the poor peasants made its appearance, battling for the break-up of the huge landed estates under the famous slogan of “Land and Liberty!” The two movements ran more and more into one mighty current, unburdening themselves of inadequate leaders along the way. From 1913 onward the revolutionary stream widened perceptibly. The revolution now incorporated aspirations of the youthful but strategically intrenched proletariat. Finally, under Carranza it became definitely and aggressively nationalistic. Liquidation of clerical power became a natural point of the revolutionary program, after the ephemeral Church-supported dictatorship of Victoriano Huerta.

During the days when Carranza was marshalling his forces for new struggles after the elimination of Huerta, many states of the republic arbitrarily limited the number of priests who could officiate within their territory; churches were turned into barracks, schools, and libraries. I have seen many of these made-over institutions, which still flourish in the states where the revolutionary struggles were fiercest. It is unlikely that they ever will be returned to their original purposes.

Coming on the wave of this spontaneous succession of revolutionary acts against the Church as an instrument of the old regime, the constitution of 1917 re-enacted the anti-clerical provisions of 1857, and went beyond them. The present document forbids foreign priests to officiate in Mexico, excludes the clergy from all participation in politics and even prohibits Catholic periodicals from criticizing the government in any way.

The Mexican revolution may be said to have been in power throughout the presidential terms of Carranza, Obregon and Calles. There were governmental compromises and betrayals during these last ten years; but throughout the period the aroused workers, peasants and petty-bourgeoisie have been the center of gravity in the political life of the nation. The political atmosphere of the country has been “radical.”

When the armed struggle died down, however, many things intervened to lighten the pressure of the triumphant revolution upon the Church, as upon other institutions. There was even sometimes a tacit understanding that some of the anti-clerical provisions of the constitution might be allowed to become dead letters. The defeated forces of the old regime were struggling for some kind of a foothold again. The process described at the outset of the present article was taking place.

The attitude of the reaction became a standing challenge. The crisis with the church was brewing all thru the last years of Obregon’s presidency.

With the decisive defeat of De la Huerta’s revolt the national revolutionary elements were in a position to take the offensive. Calles began to work out his program for the building of an independent national economy in Mexico. He set out to apply the national-revolutionary provisions of the constitution. On July 3rd, Calles issued a set of decrees putting the anti-clerical provisions into execution, beginning August list. His decrees moreover denied to periodicals with even a general clerical tone the right to criticize acts of the government.

Instantly there was tumult. In a sense the attitude of the government had been assumed without warning, although it was foreshadowed in the deportation of papal legates and in a generally increasing aggressiveness toward Rome which could be traced back to the last years of Obregon.

No doubt Calles’ move is partly influenced by the fact that a presidential campaign is approaching in Mexico. Workers, organized peasants and petty-bourgeoisie make up by far the most active elements politically of the electorate. Calles has tried to base himself on the workers and peasants, but he has shown a repeated disposition to subordinate their interests to those of the numerically weak petty-bourgeoisie, a circumstance which has even led to compromises with American imperialism. Even the workers affiliated to the official and officially-favored Labor Party are tired of getting no more revolutionary stimulant than slogans about accepting wage cuts for the benefit of national industry. The peasants have still more serious grievances, notwithstanding that the Calles government has given out titles for partitioned lands and is furthering peasant co-operatives. Calles’ candidate could not win against a strong contender such as Obregon—if Obregon should be the opposition—unless the government took energetic steps to enhance its revolutionary prestige. At the present time no matter what electoral combinations may be formed, Calles has the undoubted prestige of leading the anti-clerical struggle.

What, in a larger sense, is the government objective in this anti-clerical offensive? One might say that, hewing to the line of the constitution, it is directed only against the political power of the Church. But what is political? What is left of the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico after the new laws and regulations are in effect? No Church property, no monasteries or convents, no foreign officiates, no ecclesiastical vestments outside of church buildings, no control over elementary education, no polemical press. The very substance of Catholicism must be changed under such circumstances. Anyone who understands the ramifications of Catholic authority must realize this.

Mossbacked American editorial writers ask: How can an anti-Catholic movement triumph in a Catholic country? But this is exactly what happened throughout most of Europe during the Reformation. The Mexican people are throwing off Catholicism. Whether a modified hierarchical form, or something else, will take its place remains to be seen. The attempt to set up a Mexican Schismatic Catholic Apostolic Church, initiated last year with the obvious support of the government, has quite apparently failed. It is possible that the peasants, the masses of whom are religious, will eventually group themselves around their local priests. One thing is certain: Mexico’s Reformation will not and cannot follow the classic European lines.

The whole course of modern Mexican history tells us that the anti-Catholic movement is part of a great Mexican revolution which could not reach fruition while leaving the feudal Church intact.

What is perhaps the most obvious aspect of the present conflict in Mexico is that while it began as a government offensive, the Church quickly and energetically took up the challenge, striving to convert it into a clerical counter-offensive. Fortified by the letter from the Pope and full of hopes of aid from the United States as a result of a tacit concordat at the Eucharistic Congress at Chicago, the Mexican clericals decided upon open rebellion. With the priesthood and lay Catholics on one side and the united national-revolutionary forces on the other, the contest become a vital test of the revolution. De la Huerta’s declaration from his Los Angeles retreat that he was ready at any time to engage in a new armed movement for “religious liberty” was, of course, wholly to be expected.

That on the strength of the present contest the Church stands defeated is a tribute to the fundamentally sound class basis of the revolution.

However, the Church struggle will last. It will last because it is a struggle to activize politically the potential reactionary supporters on which a permanent post-revolutionary opposition must base itself. It is an attempt to throw these elements into motion. To awaken them from the stupor to which the long years of revolutionary supremacy reduced them, and to make them contesting factors with the working class and petty bourgeois elements who have for so long dominated the Mexican political atmosphere. One can expect the Church conflict to be a factor in the next presidential elections.

It will last because there is a basis for it in the Mexican class structure.

And it will last because of constantly renewed inspiration from the imperialist nation across the northern border.

Even now the government of America’s oil magnates, mining lords and money kings is playing more than a passive role in the Mexican situation. So much secrecy enshrouds the latest U.S. note to the Mexican government at this writing that it is difficult to say what its contents may be; but whatever it may contain, the note has been sent. And it is a hostile act of considerable importance.

President Coolidge makes solemn official declarations to the Knights of Columbus that the United States cannot intervene in such a purely domestic matter as the Mexican Church conflict. But at the same time he dispatches another of his threatening messages to the Mexican government, probably again opening the whole controversy of Mexico’s oil and land laws.

The purpose is clearly to embarrass the Calles government at a time when it is face to face with reaction at home, thus lending aid to the clericals.

Incidentally it reveals the whole line of American imperialist policy from the beginning of the Church struggle. The policy is not a new one with regard to Mexico or to other countries of Latin-America. Wall Street and Washington recognize the Catholic Church as a valuable ally of American imperialism, but the complex of forces in the United States itself makes it impossible to support the Church exclusively on Church issues. Consequently, the Church is supported through covert insinuations at a Eucharistic Congress and through official protests over the perfectly legal deportation of a Catholic archbishop who happens to be an American citizen. In the course of the present Catholic rebellion, Ambassador Sheffield, out of a blue sky, hands the Mexican government a threatening note. U.S. intervention—still only diplomatic it is true—becomes a fact, although crystalized around issues quite apart from those raised by the Church conflict.

What can the United States want from Mexico regarding the oil and land laws? The government declared months ago that it was satisfied with President Calles’ regulations modifying their enforcement. In these regulations Calles gave practically everything that was immediately asked. What is then the issue with the Mexican government?

The revolution is the issue.

Mexico is a relatively small nation bordering on the most powerful imperialist country in the world. The maintenance of a national-revolutionary program in Mexico is a challenge to the most cherished imperialist aspirations of Wall Street, which include nothing less than the complete subjugation of the republic lying across the Rio Grande.

The latest note to Calles’ government may be just an isolated thrust or it may be followed by a general assault against Mexican sovereignty. But whether or not the note is followed immediately by others it cannot properly be regarded as an isolated one. It is part of the general ever-intensifying push forward of American imperialism against Mexico, in alliance with whatever counter-revolutionary forces are allowed to gain strength there.

It is not likely that there will be any more direct U.S. intervention in the present crisis. The Catholic rebellion failed to split the revolutionary forces and thereby create a favorable situation for imperialism.

The Mexican government will be strengthening the revolution in the face of all its enemies, native and foreign, if it acts with energy in the present crisis. Unless there is a rapid shift in developments the Church will emerge from the present conflict with its prestige badly shattered. The government must grasp this opportunity to remove clericals from strategic positions everywhere, to put out of harm’s way all those who have taken an active part in support of the clerical rebellion to root out every remaining vestige of clerical power—and to base itself more and more decisively upon the toiling masses who must be the backbone of its support. The extent to which Calles adopts such a course will determine its true revolutionary character.

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1926/v5n11-sep-1926-1B-FT-80-WM.pdf