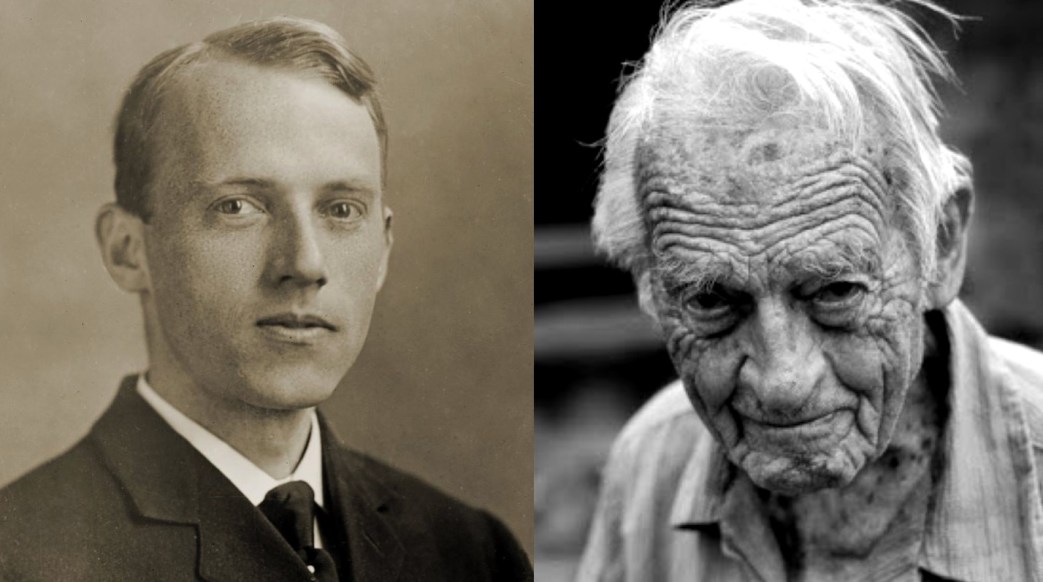

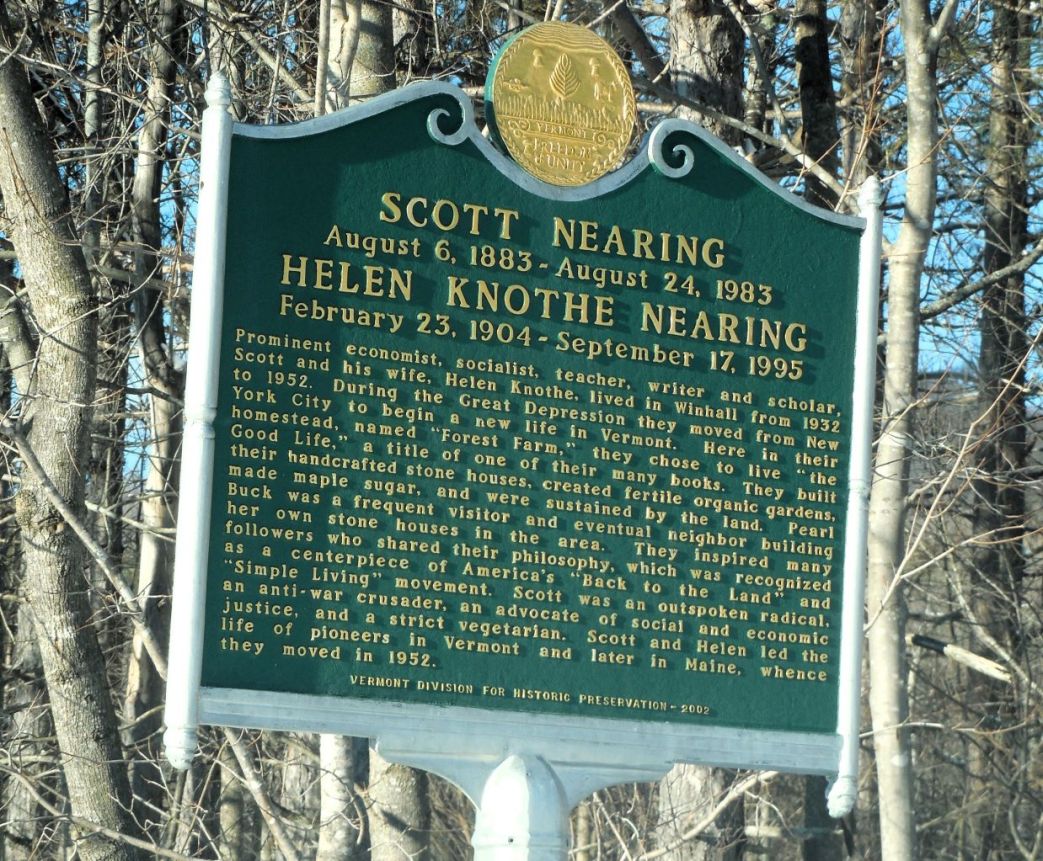

Always an independent thinker, Scott Nearing with an early entry into the ‘growth’/’de-growth’ debate.

‘The Lap of Luxury’ by Scott Nearing from The Liberator. Vol. 6 No. 6. June, 1923.

(Prepared for THE LIBERATOR from a lecture delivered at the Rand School.)

A LABOR organizer, in speaking of his Buick car, said to me recently: “The best the country affords is none too good for the workers and the organizers of the workers.” Not all of the workers whom he had organized, however, had Buicks. Gompers makes a thousand dollars a month as President of an organization, some of the members of which are getting twenty-five dollars a week. How far is this going to go before you say to the president of a union: “You have had enough?” By contrast, the I.W.W. has always taken the position that the man in the office shall get the same salary as the man on the job. There are two sharply contrasted theories as to whether the worker should stay with his own class economically or should get all he can. There are rich Socialists whose economic interests pull them in one direction while their political interests pull them in another direction.

Necessity is a combination of those goods and services which maintain health and decency, so that one does not go dressed in rags in a community where people do not wear rags, or is not housed badly to the point of attracting attention. Comfort is anything above necessity which increases man’s efficiency and social usefulness. Luxury is anything beyond that. You will see at once that luxury cannot be defined in so many dollars a week, for the standard will differ for each member of the community. Nevertheless, this standard constitutes a real challenge and presents a real issue.

There is the well-known formula of Bentham and his school of utilitarian philosophers who hold that happiness of the individual depends on what he possesses because each economic good carries with it a certain amount of happiness or capacity to satisfy man’s wants. An apple satisfies hunger; shoes provide comfort, etcetera, and therefore man’s happiness is dependent upon the sum of goods and services at his disposal. But the increase in the volume of happiness is not as rapid as the increase in the volume of things; if you eat four apples you do not get as much pleasure out of eating the fourth as you do out of the first. That is the law of diminishing utility. Yet, Bentham concludes, a man with more things would be happier on the whole than the man with fewer things. This is the foundation of modern thinking in the Western world, that the better off you are economically the happier you will be. You want to have at your disposal the things that are at the disposal of the best people. Who are the best people? The people who have the most things, live in the best houses, wear the best clothes, and eat the best food, and so you strive for these things so that you may become one of the best people. We have accepted, hook, bait, and sinker, this utilitarian philosophy of Bentham.

Socrates, on the other hand, in speaking of economic goods, said that to have no wants is divine, and that to want as little as possible is our nearest approach to divinity. These two doctrines come into conflict in the life of every individual who is in a position either to have luxury or to think of having luxury. Which one is sound? Granted that a man needs the necessities of life, and that comforts add to his usefulness how about the additional things? Are they desirable or undesirable? The people of the United States are in a better position to answer that question than the people of any country have ever been. In no other country have Tom, Dick, and Harry been taken out of the ranks and given such great quantities of superfluous things. Tens of thousands have become rich over night and have been able to enjoy every advantage that wealth can command. Are they better or worse off? Is it true as a general principle that the best in the country is none too good for them and that the best in the country means luxury?

What effect has luxury had on the people who have secured it? From what we hear about the rich we may conclude that many of them are profoundly unhappy. The possession of many things, therefore, has not brought the promised satisfaction. The reasons are manifest. The psychology of many possessions is bad; it is as disastrous to live among many things as it would be to spend all of your time at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where your attention would be constantly diverted by the variety of things about you. If a room has too much furniture in it it is difficult to concentrate on any one thing. People of much wealth have many possessions; that is why the younger generation of the wealthy are often scatter-brained people. They disperse their energies; they are not necessarily vicious but they tend to be useless because their life has consisted in a vast number of choices. They may eat a different pie every day; they can begin with apple pie and go right on down the list; they never have to go back to apple pie; this may make them a connoisseur of pie but that has its limitations. They may become connoisseurs of cut jewels and fine china but the vitalness of life is lost to them because of the extreme diffusion of their attention.

Wealth, luxury, riches, surplus, destroy man’s initiative. I do not mean that a man should go hungry, but if he has more than enough to maintain efficiency and social usefulness it tends to destroy his efficiency. What happens when a man gets money and fine things? He says to himself: “After all, I do not need to struggle any more, and my children will never have to go through the struggle I went through.” I was talking to a big robust fellow the other day, a man who had made a business success,–as to whether or not wealth should be inherited. He said that he had always got up at five o’clock and considered that a great asset. I asked him what time his children got up. He answered: “No particular time.” I asked him why he did not give his children the opportunities that had made him what he was. He didn’t quite know, but he was going to see that they had a good time in life. Because he had got away from the necessity of rising at five o’clock, which he considered an asset, he allowed his children to get up at ten o’clock and so deprived them of this opportunity. Thus the second generation are incapacitated to function; they cannot tie their own shoes; they have a servant to do it for them. They are pauperized by their relation to luxury. What is a pauper? It is a person supported by somebody else until he is incapable of self support. A rich man’s son tends to become a pauper.

Historically, age after age, the same series of events have followed one another, men have secured luxuries and have passed them on to their families and their families have deteriorated because the possession of more things than men require tends to break down the stamina of the people who have them. They are forced to spend because they do not know what else to do with their lives, and this involves the atrophy of the creative instinct in man. Living on one’s income means dying economically. He who ceases to produce the equivalent of his keep has suffered economic death.

Wealth, luxury, surplus are not necessarily desirable; Bentham’s formula follows only for a very short distance. After a man has eaten three apples, the fourth brings no pleasure, and so with everything else,–increased amounts of the commodity do not bring increased happiness.

Let us go back to the trade union official and the worker; shall we raise the salary of the president of the union from $7500 to $10,000 a year? Suppose that $2,100 will provide health and decency; allow $2,900 for comforts,– $5,000 should be enough on any basis. To add luxury is to diminish the value of the man and of his family. When men reach the luxury point they would be wise to stop. No matter what their service to the community, the world must find some other recompense than increased economic goods. The problem of the effect of surplus wealth on the wealth possessor is one of the most important that the community faces.

There is another phase, the result of varying economic standards. What happens when the president of a union gets $250 a week while many of the workers in that union get $25 a week? Take the latest income tax returns in the United States where there are 43 million people gainfully employed. According to these returns five million people get between $20 and $60 a week,–one-ninth of the total; one and one-third million get between $60 and $100 a week; one-half million between $100 and $200 a week; one-quarter million over $200 a week. Three-quarters of a million out of 43 million receive $100 a week or more. One-onehundred and sixtieth receive at least $200 a week. In the whole population only about two million or one-twentieth of the gainfully employed get over $60 a week. Of course these figures are not entirely accurate, but they are substantially representative.

By contrast, take the figures for the wages in Ohio in 1921. Four per cent of the male workers received less than $15 a week; 14 percent got from $15 to $20; 38 percent from $20 to $30; 28 percent from $30 to $40, and 16 percent got over $40. In Ohio 84 percent of all the workers get less than $40 a week. If these figures are compared with the income tax returns it is evident that in the United States at the present time a very small fraction of the people get $100 a week or over, that the great body of people get less than $100, and that at least two-thirds get less than $35 a week. We live in a world where a very small group has the necessaries plus the comforts of life, where a larger group has the necessities, and where a very big group has less than the necessities. Those people who do most of the work, who dig the coal, clean the streets, handle the freight at the terminals, they and their families are living at or below the health and decency standard.

What is the effect on anybody who lives on one standard with a surplus while other people lack the necessities? What happiness is there when one man enjoys luxuries side by side with people who lack necessities? Those are the essential contrasts which are encountered in every modern society and any discussion of luxury involves a contrast between one man’s luxury and another man’s poverty. The first effect of such a solution is to create class bitterness and antagonism and division. From the social as well as from the individual viewpoint, advantage lies not in the possession of luxury but in the common well-being of the mass of people. If raising the standard of living for one man means lowering the standard of somebody else then those on high standards enjoy luxury on some other person’s heavy labor; as Hugo says, the Heaven of the rich is built on the Hell of the poor. In present day society the luxury of the few is built on the service of the many. Social, therefore, as well as individual luxury, is a menace to the well-being of society; instead of bringing men together it creates division, and prevents any semblance of fellowship or fraternity.

There is another aspect that is comparatively little thought about,–the United States finds itself in a very unique and favorable position in the world. During the last few years it has gone through a period of extreme prosperity. In 1850 the wealth of the country was seven billion dollars; from 1860 to 1900 it grew to 88 billions and from 1900 to date, to 350 billions. Wealth has grown with tremendous rapidity, and the same thing is true of the income of the country. In 1890 the national income was nine billion dollars, in 1910 it was 30 billions, and in 1918 it was 73 billions. As compared with the other countries of the world the United States finds itself in an extremely favorable position. The turbulent conditions of the world make any estimates of wealth mere guesses, but the following figures give us some idea of the comparative wealth and debt of several countries:

Country–Wealth–Debt

British Empire, 230 billions, 45 billions

France, 100, 51

Russia, 60, 25

Japan, 40, 2

Italy, 40, 20

The total wealth of these countries is 470 billions; the wealth of the United States is 350 billions, with a debt of 23 billions.

An interesting thing is happening at the present time,— the United States is putting up a barrier against immigration. With this enormous wealth, with tremendously high standard of income, the American people are putting a fence around the whole thing. They refuse to let anybody in un- less they come to buy; if they are business men, they are welcomed, but if they are people looking for a higher standard of living they cannot come in if their “quota” is exhausted. Here is the New World formula,–luxury for America, starvation for Central Europe, and bare subsistence for the rest of the world. The American people hold an advantage which they propose to keep for themselves and their children. Just as an individual in a community sets himself up with a nice house on a hill, with silver service, a maid and a cook, and does not care how the people in the valley are living, so with America. The Americans are generous; they give to starving Russia or China, but they do not let that interfere with their three course dinner. America today is the lap of luxury of the world; it has more rich people, more income, more wealth, than there is in any other country in the world.

The attitude of the Hindu, the Chinaman, the German, the Russian to America is like that of Lazarus to Dives,–thanking God for the rich man who threw him crumbs of bread from his table. The same fact that is encountered when the individual enjoys luxury is encountered when the country enjoys luxury. Differing standards of living in a community breed civil war. The United States enjoys the good things of life in abundance, and sooner or later the group outside will come knocking at the door, and when that time comes, the United States, with one-sixteenth of the world’s population will have to answer to the other fifteen-sixteenths outside.

It is very difficult for a man to sit down in a starving group of people and eat to satiety without offering them a share. Face to face, such a thing is impossible, but it is not necessary to see them; the camouflage of modern life removes that danger. One-sixteenth of the people of the world are living in the United States with a tremendously high standard of living, and among the other fifteen-sixteenths hundreds of millions are living in misery.

Can one group of people expect to monopolize wealth and keep hold of it? No, it is not practicable. Can one group in a community live in luxury and let others go hungry? No. Can an individual live and be happy in proportion to the amount of luxury he secures? No, the volume of wealth is a source of unhappiness rather than happiness. Can a man expect to live in luxury while other lack necessities, build happiness out of luxury, look to luxury in any form as a personal advantage? No, luxury is a source of personal deterioration and a community menace, and the individual who has his own well-being at heart will refrain from luxury as he would from any other menace.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1923/06/v6n06-w62-jun-1923-liberator-hr.pdf