Chandler Owen and A. Philip Randolph, the editors of The Messenger, leave the city in August, 1921 for a vacation at the International Ladies Garment Workers Union’s Unity House in the Pennsylvania mountains, the retreat’s first Black guests.

‘A Vacation’ by Chandler Owen and A. Philip Randolph from The Messenger. Vol. 5 No. 11. November, 1921.

WE were tired. A long winter of work and worry combined with a sweltering July had brought us upon the brink of breakdown.

Rest, nature’s balm, called. Dreams of vacation haunted us. The goddess of Leisure beckoned us on. Where to go was settled without much deliberation. The Ladies Waist Makers of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union had a great resort — The Workers’ Unity House, Forest Park, Pennsylvania, in the heart of the Blue Ridge Mountains. It is open to all persons of labor and radical sympathies, so that labor and radical educators, journalists and teachers are welcome.

Early in August we dropped everything, and with cases packed for vacation, proceeded to Forest Park, where we arrived about three o’clock in the afternoon.

When we motored into the grounds we were greeted by a great arched sign which reads: “Welcome Unity House!” As we stepped out on the spacious porch of the main building a little girl, Miss Bessie Switzsky, the manager, escorted us to the register. This completed, we received a supply of towels and were shown the way to our room. It was room number 26, in one of the cottages, spacious, airy, light, with a large private bath and a glass door permitting porch exposure.

Dusty and dirty from the travel by train and auto we immediately tested the refreshing utility of the tub. We next attired in regular vacation style,–doffing our hats, collars, ties and coats, and turning in the collars of our shirts.

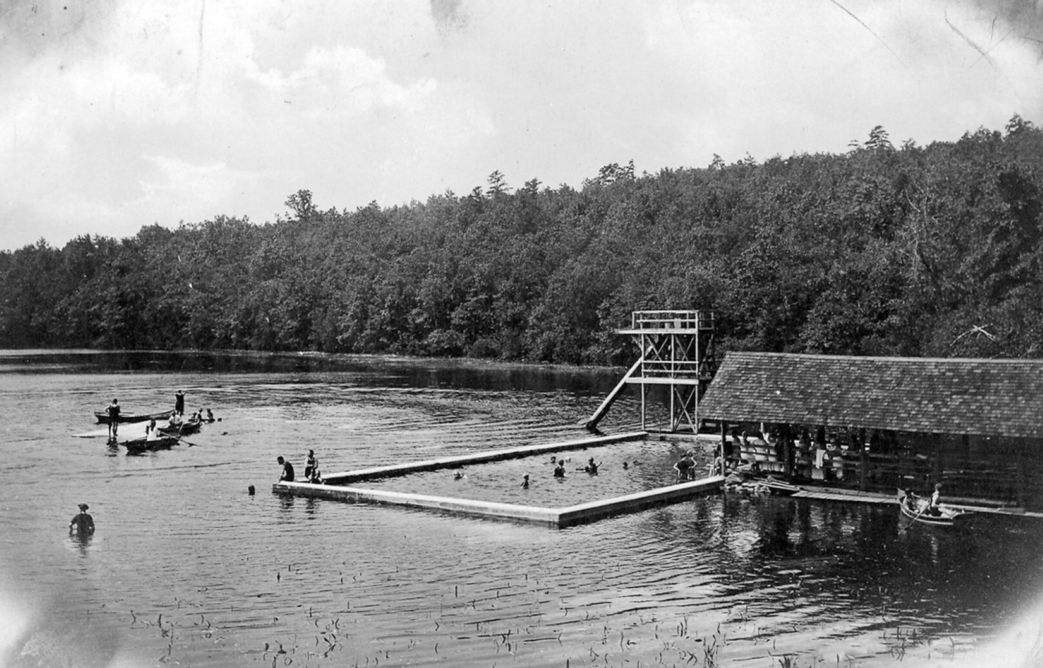

It was a hot day. The humidity was high. We yearned for water–not to drink but to bathe in, to drink from its cool current of air. Forest Lake affords both. There is something fatally fascinating about water anyhow, but this lake emmeshed between mountains, always placid except for the lapping waters and the paddling oars, veritably lures. And here we spent much of our stay at Unity.

When we returned from the lake it was nearing 6:30, the dinner hour. Persons were stretched all over the green lawns–some taking sun baths, some drying after a lake plunge, others seeking the coolness of shade beneath the gentle maples, the giant oaks, the bending birches, the sweet scented cedars.

Suddenly, we saw them rise as though some intense stimulus had actuated them. It had. The dinner bell, described by one cynical fellow as the favorite orchestra there, had rung. To us it was not unwelcome either. We went into the long dining room where we were seated at the administration table. Later we were seated at the artists’ table. The evening was clear. For a moment we looked out across the lake and spied the mountains soaring above the treetops, thrown into bold relief against the velvet purple of the sky. It was beautiful, but we were too hungry long to indulge our poetic tastes. Utility prevailed over esthetics; we deserted the landscape and gratified our gustatory appetites.

The first morning we missed breakfast in favor of sleep. So rare was such procedure that every- body was sure we were sick. Afterwards we never again missed a meal,-not so much to save the management anguish, but because we felt the “Call of the Wild” Wolf-Hunger.

Dinner over, we began to examine the physical plant. In this respect Unity House is ample and exquisite. There is one large hotel together with eleven large cottages. Many of the rooms have private baths. Electricity, hot and cold water, are in every When one wants to walk, when the wanderlust pricks and goads, there are nearly 3,000 acres of land over which he may roam, for the Rand School with its Camp Taminent has 2,000 acres in addition to Unity’s 1,000 acres, over which a guest at either place may perambulate to his heart’s content.

If it rains at Forest Park, nothing stops but tennis, which was our favorite game. Each building is united to all others by connecting sheds which make a complete oval of the lawns and hotel grounds.

When the day was done and the night fall descended upon that park in the mountain forests, nearly everybody sat on the long piazzas, lounged in the lobbies, strolled over the campus, or went to the lake.

The day is over; the cool kisses of twilight lull to leisure, recreation or sleep. At 8:30 p.m. sharp the music strikes up in the dance hall. It is music led by Miss Sadie Beckler, the pianist, and gets the feet panting and the shoulders yearning to trip the toe. Besides, the dance hall is beautiful, shapely in design, flushed with the lake air, and gently located upon the crest of the hill overlooking Forest Lake.

A few nights the dance was cut out in favor of a bonfire. This suggestion came from the very competent physical and recreation director, Mrs. Mildred Fox. By the use of flashlights many would worm their way through a winding path to an opening beside the lake which no doubt has been used many years for a bonfire purpose. Others more adept at canoeing and swimming would go out in the boats, row up to the bonfire and take turns in singing and reciting after those on shore would cease. When the bonfire would close the shore group wandered back through the woodland path while the rowing party paddled to the pier, meanwhile emitting mirth, nay, wafting bubbles of laughter over the rippling but tranquil waves. Then lazily we climbed the hill homeward, loitering the while, quaffed the quickening air from the fresh grasses and inhaled the fragrant odors from ripening grapes.

Both Unity and Camp Taminent gave their respective guests some good concerts. The Labor Day Concert of Unity, however, was a rare treat. S. Goldenberg, baritone and actor of the Jewish Theatre, sang; Marcel Silesco, of the Vienna Opera House (the world’s greatest, most critical opera house) graced the occasion with his dulcet tenor. Here was a master, grand opera singer. On this occasion one of the editors of the MESSENGER was pressed into service–not to sing, but to speak to appeal for funds for starving Russia. After some debate as to who should do it, Owen was finally saddled. He took up a collection of $256.65.

Two things stood out at Forest park–one, the no lock on rooms, and the other, the absence of race prejudice. No rooms were locked; no keys. The workers were there for vacation, not to steal from fellow workers.

No race prejudice. The malicious leer of its breath was not to be seen, heard or manifested in any way. We were the first colored guests they ever had, but they welcomed all races. Race, creed and color were not the issue. We were all hand or brain workers, struggling for a new social order, fighting for a more abundant life, battling for a better world.

The organized workers have bought and are running one of the choicest cloistered retreats of the millionaires–running it ably and without race prejudice, whether in dance hall, in bathing pool, on lake pier or in dining room. And this, let it be remembered, in America, the America of the lynching bee, the Jim Crow Car, the Ku Klux Klan, the disfranchised Negro, the black peon, the proscribed!

Gentle reader, is this not a lesson which labor is teaching those poisoned by prejudice?

The Messenger was founded and published in New York City by A. Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen in 1917 after they both joined the Socialist Party of America. The Messenger opposed World War I, conscription and supported the Bolshevik Revolution, though it remained loyal to the Socialist Party when the left split in 1919. It sought to promote a labor-orientated Black leadership, “New Crowd Negroes,” as explicitly opposed to the positions of both WEB DuBois and Booker T Washington at the time. Both Owen and Randolph were arrested under the Espionage Act in an attempt to disrupt The Messenger. Eventually, The Messenger became less political and more trade union focused. After the departure of and Owen, the focus again shifted to arts and culture. The Messenger ceased publishing in 1928. Its early issues contain invaluable articles on the early Black left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/messenger/1921-11-nov-mess-RIAZ.pdf