A valuable explanation of the organs of power in the Soviet state as established by the 1918 Constitution and developed in the first years of the Revolution. In six parts: I. The All-Russian Central Executive Committee, II. The Council of People’s Commissars, III. The Council of Labor and Defence, IV. The All-Russian Congress of Soviets, V. Local Soviet Congresses, VI. Town Soviets.

‘How the Soviet Government Works I: The All-Russian Central Executive Committee’ from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 6 No. 1. January, 1922.

(The following is the first of a series of articles on the institutions of the Soviet Government which we are reprinting from “Russian Information and Review”, published by the Russian Trade Delegation, London.)

IN spite of the publication, over three years ago, of the Soviet constitution, the nature of the organs through which the Government functions, and the methods of its work still remain an impenetrable mystery to the vast majority of even its friends in western Europe and America. It is unnecessary to discuss here the reasons for this; it is sufficient to state, with no fear of contradiction, that very little is known of the supreme organs of authority in Russia except that they issue decrees. The following sketches of the principal State organs are intended as an introduction to a wider and more detailed study of their work.

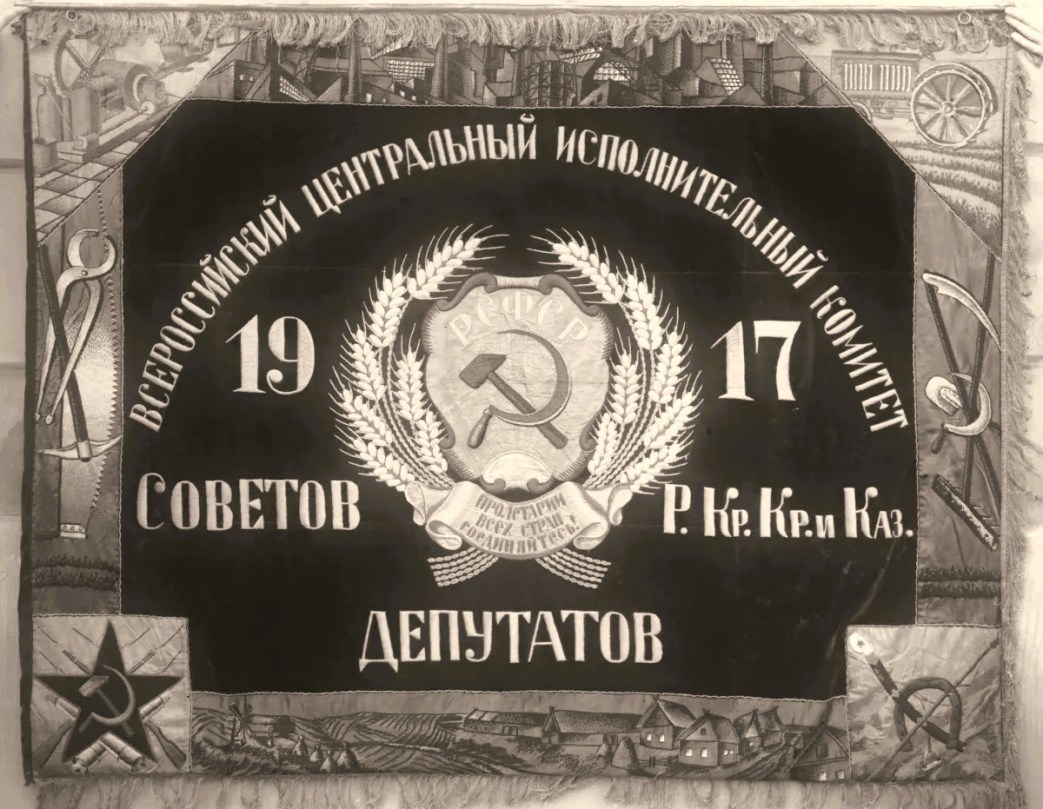

The All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets was created as early as June, 1917, when the Soviets had not yet assumed State authority. From a central unified executive organization, elected by the General Congress of Soviets from all over Russia, it naturally became the central and, between congresses, the supreme legislative body when the great change in the position of the Soviets took place in November, 1917.

The A.R.C.E.C., according to the constitution of July, 1918, which was based on the practice of twelve months, consisted of 200 members elected by the All-Russian Congress. This number was increased at the eighth congress in December, 1920, to 300 members. At first the builders of the Soviet constitution conceived of an A.R.C.E.С. as a legislative body in more or less permanent session, working, consequently, in much the same way as western Parliaments, although its functions were much wider. Further experience, however, showed that the demands of the working masses for constant control over and contact with their representatives, the ever-present danger that those representatives would lose the vital acquaintance with local conditions which is essential for a revolutionary government, and the extreme shortage of practised experienced administrative workers in the districts, all combined to make it impossible for the A.R.C.E.C. to remain constantly in session at Moscow. Since the beginning of 1920, therefore, the A.R.C.E.C. meets regularly once every two months for approximately a week. At these sessions it considers all decrees affecting political or economic life, or introducing radical changes into the existing State institutions. The regular reports of the People’s Commissariats, or ministries, are considered at these sessions. The reports of the presidium, or standing committee, relative to the execution of the decisions of the last session during the intervening two months, and of various sub-committees appointed to work out specific questions, are also submitted and discussed.

In practice the net result has been that only those members of the A.R.C.E.C. remain in Moscow who are (1) engaged on work in one of the People’s Commissariats or State inter-departmental commissions; or (2) detailed for specific work by the A.R.C.E.C. either as members of the presidium or as representatives of the А.R.С.Е.C. on various public bodies. The majority of the members, however, are engaged between the sessions on important work in their own provinces, members of executive committees, chiefs of departments, and so on.

Detailed statistics are available to illustrate the work of the All Russian Central Executive Committee between January 1 and May 1 of the current year. At the three sessions 700 questions of a current nature were discussed, 132 being brought forward by private members, seventy-five by the People’s Commissariat for Transport, sixty-nine by the Supreme Appeal Tribunal, and so on. The nature of the questions discussed is as follows: 353 administrative (involving questions of provincial boundaries and control of the activity of the People’s Commissariats and local executive committees) and 205 judicial (questions of amnesty, appeal; etc.) | During these four months thirty-five commissions were instituted. Of these, five were in connection with draft projects for creating autonomous republics, five for reviewing the work of various institutions, four on questions of general administrative organization and questions of local government, four on judicial questions, and the remainder on economic questions and questions of the internal administration of the A.R.C.E.C. itself.

Characteristic of the work of the A.R.C.E.C. is its “waiting room” in which any worker or peasant can see members of the highest legislative authority in the country without any annoying formalities and through him approach the presidium of the A.R.C.E.C. This institution, in fact, realizes in real life the long-dreamt-of ideal of the most advanced democrats, namely, the right of private individuals to initiate public legislation — which has never before been attained so effectively. During these four months, 1667 such cases were registered, and 389 of them were raised by peasants.

To complete the picture of this unprecedented legislative body, which is at the same time a working institution, both as a unit and in the person of each of its members, it is necessary to quote from the standing orders of the A.R.C.E.C., published in December, 1919, the provisions relative to the members. No member may be arrested without the consent of the presidium or the chairman of the A.R.C.E.C.; traveling expenses of the members are allowed by the presidium when they are traveling on public work; they may take part in a consultative capacity in the proceedings of all local Soviets and executive committees; they have the right, on production of their mandate, of admission to all Soviet institutions and departments to obtain information on any point they require. On the other hand, no member of the A.R.C.E.C. may refuse to execute any task assigned to him by the presidium; every member must be actively engaged in Soviet work, either in a central or in a local organ of the Government; members of the A.R.C.E.C. who have failed to attend three successive sessions without adequate reasons forfeit their seats and are replaced by reserve members, or “candidates”, elected at the same time as the A.R.C.E.C. at the All-Russian Congress; all members receive salary at fixed rates from the А.R.С.E.C., and receipt of additional salary or income from any source is forbidden.

Summarizing the foregoing, it is clear that the All-Russian Central Executive Committee is specifically the organ which co-ordinates the activities of the local Soviet authorities and of the central Soviet organs; legislating, administrating, and exercising judicial functions at one and the same time. Its businesslike sessions and its quick and sensitive ear to the requirements of the masses make it a peculiarly successful example of the spirit of the Soviet Government.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v6-7-soviet-russia%20Jan-Dec%201922.pdf