A wonderful look at details of a season of the venerable Work Peoples College in Duluth from one of its instructors. What began as a center for the Finnish Socialist Federation of Duluth in 1907, Työväen Opisto, quickly grew as a dollar of dues a year for each member of the Federation nationally was invested into the school. In the 1915 split in the Federation, the school went with the syndicalists. Further changes in that wing led to the Industrial Workers of the World taking leadership of the college in the 1920s. Running until 1941, the school was among the most important institutions of the radical U.S. working class in our history with a great number of important activists attending as students or as educators.

‘The Story of the Past Winter Semester at the Work Peoples’ College’ by Clifford B. Ellis from Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 4 No. 1. May, 1926.

THEY had seen much in life. They wanted to know its meaning—to interpret it in terms of their own experience. They were a motley gathering. There were over seventy men and a few women—all of the working class. Some were sailors who had sailed the seven seas and been in half the ports of the earth. Some came from the mines of Montana and Wyoming. There were sheepherders from the sage-plains of the Far West. There were craftsmen of various trades. Saskatchewan and Alberta sent their contingent and there were boys who had followed the cycle of the harvest from Texas to the Dakotas, and who knew every yard bull and hardboiled “push” from Denver Bob and Ole of Ashland to Maricopa Slim of Arizona and Jimmy Under-the-belt of Minnesota. One had beaten his way in the dead of winter from far Saskatoon, with his tuition money concealed upon his person. There was just enough money to make it. There was nothing left over for railroad fare. It was below zero. Much of the way he had to ride outside, exposed to the icy blasts of an almost arctic winter. But he was there. Such is the thirst for education among the workers.

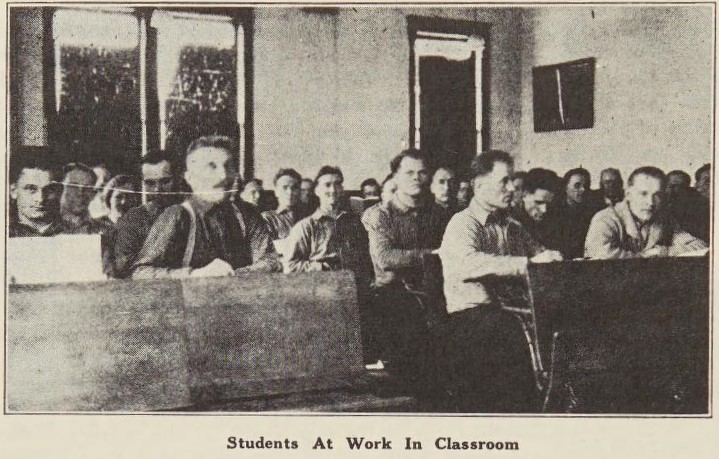

The bell tinkled in the long hall. From the dormitories down the stairs came a rush of many feet and they gathered in the class rooms, eager, expectant, is search of the knowledge that would aid in the struggle to break the shackles of slavery that bound their class. They had saved and skimped and foregone many comforts to get together the price of this season of study and here they were. The winter semester of the Work Peoples’ College was open.

Internationalism of I.W.W. Shown

Only the I.W.W. could have inspired such a gathering. In one group of nine English-speaking students there were represented Sweden, Ireland, Canada, Scotland, Germany, Finland, Russia, America and England. They were of various ages from pink-cheeked twenty to grizzled forty-five. Some had a primary education; some had passed the grammar grades, and a very few had advanced even further. But in all there persisted the same conviction. The capitalistic interpretation of life was false to the workers’ interests and perversive of truth. The school of hard knocks had taught them that. They wanted to undo the evil of the years and get re-oriented—to understand with Jack London, ‘‘what life means to me.”

Through the windows and from the grounds about the College is the vista of Spirit Lake and its island-dotted surface. Now it was a-shimmer with ice and snow, across which the sun cast its crimson bars. Each island rose from the snowy surface of the lake, a sugar-loaf of glistening white, with dark traceries of leafless boughs fringing its shore like filmy lace. Northward lay the city of Duluth; across the lake the dim outlines of buildings gave a hint of the city of Superior; around a bend in the lake shore lay Gary, the model city of the Great Steel Baron, where everything from human morals to molasses is cut to measure and adjusted to suit the dictatorial tastes and interests of the master. Its children are born in the shadow of smoke-stacks and church spires and live their lives between the alarm-clock, the hum of the machines and, of a Sunday, the droning of cut-to-fit steel trust sermons; for Jesus and Gary are in alliance here. Nothing is allowed to happen in this model village that does not chime with steel profits.

How The Instruction Is Given

And under the very shadow of this steel trust citadel, it was the function of the Work Peoples’ College to teach the neglected truths of capitalist production and how it affects the workers. These workers have traversed thousands of miles for that. They had paid their hard-earned dollars for that. They had, in many cases, endured the hardships of box-car transit to reach the College for the attainment of this knowledge.

How could this be accomplished? Economics and sociology are not easy subjects to teach or to acquire. If scholars of careful training find Marx, the sole capable exponent of capitalist production, difficult and obscure, how were these men to be expected to grasp his difficult analysis of value and surplus value? How could the complex problems of sociology, with their roots in human origins and psychology be made clear to these men whom capitalistic greed had forced from school at the very dawn of life?

The first lesson of the morning session was in economics. The class period was from eight to nine o’clock. We opened with the reading in class of Mary E. Marcy’s “Shop Talks on Economics.” Its words are simple. Its lessons are direct. They reflect the daily experience of the worker. The students read each a paragraph at a time. From the blackboard the instructor followed step by step, turning now and then to the board to illustrate in graphic outline some cogent lesson of the text. The students were earnest and attentive. They did not laugh when some reader stumbled over an unfamiliar word. They were there to help, not to ridicule.

Making The Grade To Marx

At nine-fifty the session bell sent its tinkling summons through the halls and the classes filed out to realign themselves in other classes, or to repair to their rooms for an interval of study. The courses were elective. In the twenty class-room hours per week which constituted the elective course of the average student, English grammar and composition, arithmetic, translation, public speaking, bookkeeping and secretarial work, organization and History of American Labor were among those included in the courses selected by most of the students.

In the History of American Labor, Perlman’s and Commons’ texts were used selectively as sources, but broad discursions were made to include a comprehensive survey of the labor union movement of America from its beginnings down to contemporary unionism. Here comparative studies were made of the American Federation of Labor, its structure and methods, the I.W.W. in history, theory and practice, and contemporary communism. The utmost latitude for discussion was allowed and much clearer conceptions of the various movements were the result of the studies. The history of revolutionary crises was introduced and their economic causes traced. The famous dictum of Fellow Worker J.A. McDonald seemed to prevail, that “a proletarian revolution is possible in a nation of smokestacks but it can not occur in a nation of haystacks.”

In economics the introductory course in Marcy’s pamphlet furnished an outline sufficient to accustom the student to logical methods of study. A few weeks of this discipline, a period of defining terms and accustoming the student to individual application and research, and then the class was introduced to the text of Marx’s ‘‘Capital.” Paragraph by paragraph, chapter by chapter, from “Commodities” to “Modern Theory of Colonization,” the first volume was read and digested. At first by reading in class, then by direct instruction and questions, and finally the ‘entire volume was reviewed step by step by interpretative lectures on the text with blackboard demonstrations.

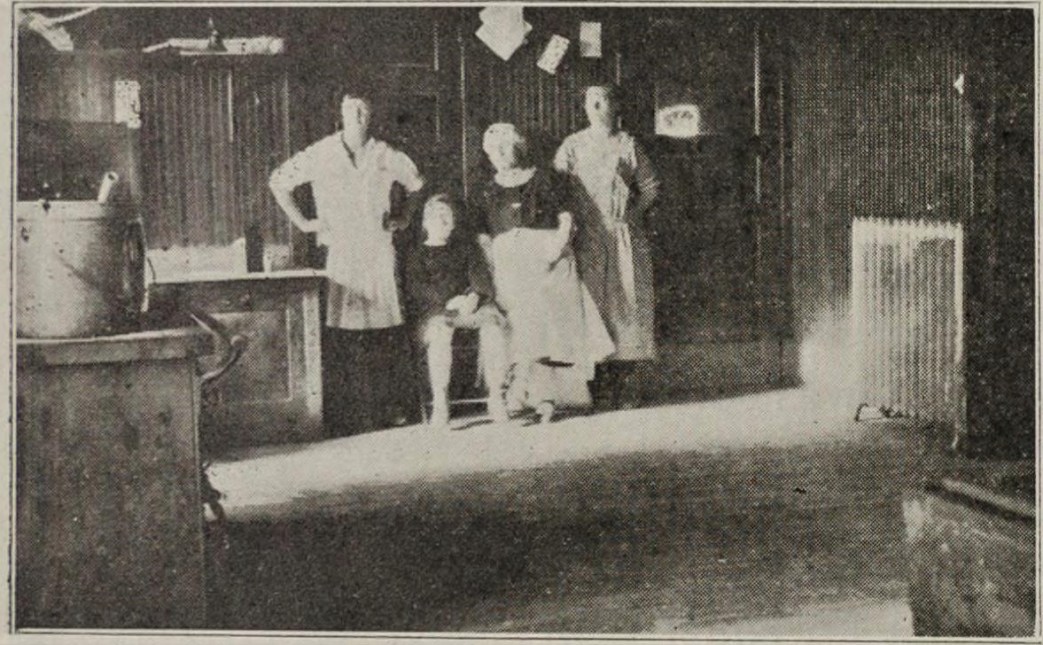

There is an interval in each mid-forenoon and mid-afternoon during which the students repair to the big kitchen where coffee simmers on the great range and a light lunch is laid out for all to help themselves. It breaks the monotony of class-room tension and lends a social atmosphere of home to the daily routine. At noon the community dining room with its long tables is filled with hungry students and again at six o’clock, dinner is served. The food is wholesome and plentiful. From the dinner hour until bed-time coffee is kept piping hot on the kitchen range and the students are at liberty to help themselves at will.

Sociology, Biology, Anthropology

The first subject of the afternoon is sociology. The introductory text used was Engels’ “Origin of the Family.” The same method as in economics was used. Reading from the text was followed by discussion. Difficult terms and passages were defined and interpreted and side lights thrown upon the subject from historical and sociological source books. This work was followed by Lester Ward’s “Dynamic Sociology.” These methods demonstrated the capacity of the average mature worker to follow even the most difficult text if properly introduced. The class in sociology not only followed the rather abstruse pages of Ward, but entered into the subject with enthusiasm and understanding beyond that of the average student of greater advantages in antecedent training. Throughout the course, excursions into biology, psychology, geology and various related branches were made. The different theories of evolution, the theories of Lamarck, Darwin and Weismann as well as the mutationists, Mendal and De Vries, were analyzed and compared. “Ancient Society” by Morgan was discussed in the light of Morgan’s later critics, the pluralists, Tyler, Boas and Goldenweiser, and Vern Smith’s series in the Pioneer, “Was Morgan Wrong?” came into service as source material. Theories of population, from Malthus to Spencer, were discussed and tested by modern statistics and data.

In the field of social research, applied methods, surveys and direct investigations were unnecessary. Not a student but had garnered in his own experience sufficient practical aspects of life and adventure to furnish abundant illustrative material. There was a sailor, a Russian by parentage, who had roamed the ‘‘Never-Never Land” of North Australia; who knew the street of Buenos Ayres and the Boca of Rio as well as he knew the purlieus of South Chicago. He had deserted the sea and wandered to the plains of Colorado and Wyoming where he herded the woolies. He had traversed the scenes of Zane Grey’s novels, knew the site of the Hidden Valley and had personally met the inhabitants of Robbers’ Roost. And he could interpret his impressions. Read this free-verse genre picture of the sheep-herder from his pen:

There was another little lad from North Dakota. He was only six feet and four inches in height and tipped the beam at two hundred and thirty. Of course they called him “Shorty” and “Little Boy.” What other name could fit among men whose lives had been filled with contacts with the ironies of existence? ‘Little Boy’ had wandered far. He knew the plains of Texas and the pavements of a dozen great cities. Bronzed and hardy, he had such physical strength and health as all men might envy. He knew life. He wanted to know its deeper meanings. And both he and the sheepherder-sailor were energetic in their pursuit and acquirement of knowledge. They entered with spirit into the class discussions, took copious notes, seized upon the technique of study readily and browsed through the library, entering upon new fields of discovery like

***stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He stared at the Pacific; and all his men

Looked at each other with a wild surmise,

Silent upon a peak in Darien.

One of the characteristics so frequently observed among these working class students is the remarkable taste for the excellent in literature. Perhaps it is because they are still intellectually vigorous with the vigor born of insatiety; perhaps it is their intimate contacts with practical existence that gives them a true sense of artistic values; but however that may be, they quickly grasped the finer shades of meaning of such artists as Swinburne, Tennyson, Omar Khayyam (Fitzgerald), and the more obvious if still pleasing quality of Robert W. Service. Love of art is not necessarily coupled with aesthetic degeneration, in spite of the cubists and the longhaired denizens of Greenwich Village.

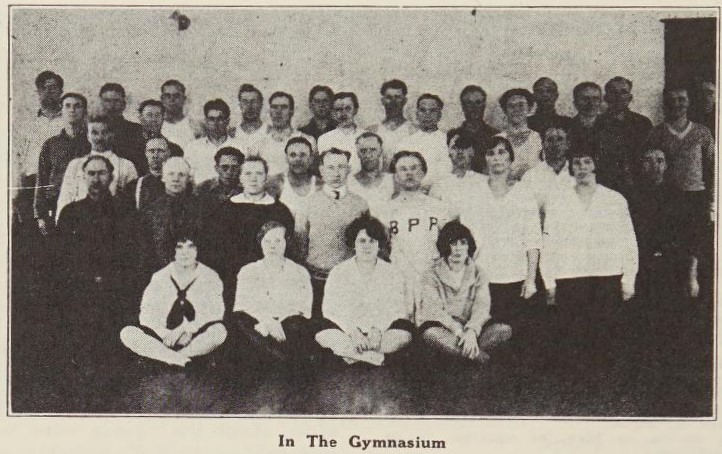

Physical Exercise, Debates and Socials

As winter progressed, the lake froze solid. Long walks over its glassy surface and excursions afoot about the islands were made for recreation and exercise. Skating was indulged in by those who fancied it for it is less than a stone’s throw from the College grounds to the lake shore. At night there were dances and debates on subjects of interest to the workers. “Birth Control,” “Is the World Growing Better?” and “Do Workers Pay Taxes?” were threshed out in the light of Marxian economics. There is a gymnasium equipped with apparatus, parallel bars, rings, boxing gloves, wrestling mat, etc., and regular classes were trained by a physical director. The shower and tub baths are next to the gym and there is ample accommodation for all the students.

Spring Means The Exodus

Spring came. The winds grew softer and the snow disappeared from the landscape. Little sparrows chirped under the windows, winking at their mates and suggestively bearing stray bits of moss and grass in their bills). The sun crept northward and the days lengthened. The season of labor was at hand. One by one or in pairs the students turned to the “point of production.” Some went to the mines. Others with gaze far afield and the long, long thoughts of youth, “grabbed an armful of box-cars” and beat it westward to the farms of Dakota. Some turned again to. the sea, their chosen field of labor. The classes thinned to a lingering few. Capitalism does not permit its slaves to tarry long at study or recreation. If the education of the workers is to progress, it must be by persistent effort and sacrifice upon their part. If these students are to return for another term, they must make and save another winter stake during the summer.

The season was a successful one. The need for working class education in their own interest is evidenced by the continued elimination by capitalistic universities of progressive instructors. Even as I write, there lie before me clippings from the Denver Post recounting the dismissal of two members of the faculty of Denver University for delving too deeply into the facts of the workers’ lives. And last week, Scott Nearing was debarred from the campus of the University of Minnesota. If there is no need for a workers’ college, why in the name of so-called “social control” do the capitalists seem so eager to convert their own institutions into instruments of class rule and propaganda? Listen to this from Lester Ward’s ‘Dynamic Sociology,’ Vol. II.

“It must not be forgotten that a system of education to be worthy of the name must be framed for the great proletariat. Most systems of education seem designed exclusively for the sons of the wealthy gentry, who are supposed to have nothing else to do in life but seek the highest culture in the most approved and fashionable ways. But the great mass, too, need educating. They need the real, solid meat of education in the most concentrated form assimilable. They have strong mental stomachs, and little time. They can not afford to take slow, winding paths; they must move directly through.”

Men interpret life in terms of experience and education. They reason from such data as they have acquired. There is no such thing as a line of division between the theoretical and the practical. Learning is vicarious experience. The workers must stick to the first star of the I.W.W. emblem and continue to educate as well as to agitate and organize. By so doing they will continue to build “the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.”

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/industrial-pioneer_1926-05_4_1/industrial-pioneer_1926-05_4_1.pdf