In the immediate aftermath of the ‘Ludlow Massacre,’ Max Eastman gauges the class war in Trinidad.

‘Class Lines in Colorado’ by Max Eastman from New Review. Vol. 2 No. 7. July, 1914.

A single motion brought us all to the platform as the train pulled slowly past those ruins at Ludlow, and with incredulous eyes we saw the broken black acre of desolation that is a monument to the National Guard of Colorado. I think every heart was silenced for a moment there in presence of those ravaged homes. The naked violation of every private article of familiar life is so sharp a picture of sorrow. But it was not more than a moment. A voice out of a thin nose behind my ear so soon recalled us to our daily bread.

“What ta hell’s the use comin’ down here with soap and specialties–this territory’s been shot up!”

Is there a person with more purity of purpose in God’s golden world than the commercial traveler of America? Trinidad, he informed us, had been the best city for business, outside of Denver, in the State of Colorado, and at present you could sell more soap in a graveyard.

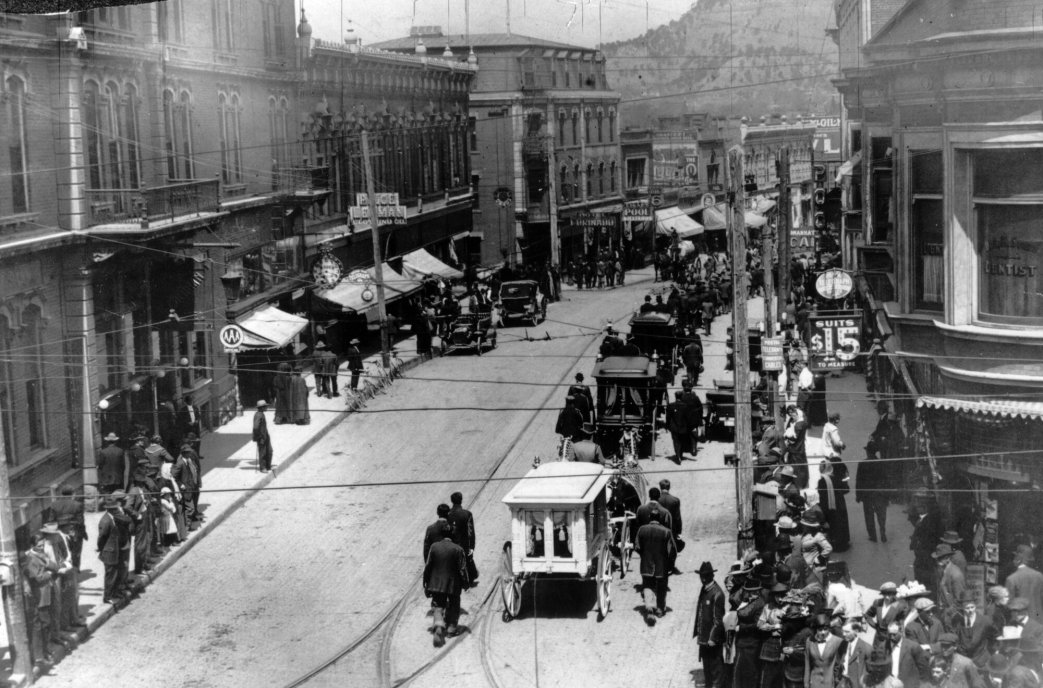

In another forty minutes we arrived at Trinidad and could verify his words. A paved, marbled, improved, modern city, shining with efficiency, ready for business, ready for a high time, a thoroughly metropolitan center. And yet the inhabitants seemed to be standing around the corners, idle and anxiously waiting for something to fall out of the sky. I have never seen humanity so stripped of pretence and cultural decorum, so bared to the fighting bone, as it is in Trinidad. They have been through a terror of blood. They have seen their government and their officers of peace evacuate, leaving the city to what seemed an army of revolution. They have either welcomed this army or moved to the cellar. There seems to have been no middle course. And whichever course they pursued, they pursued with the combined passions of a blood feud and a financial panic. Like my friend of the soap and specialties, and with hardly more disguise, they have adopted into their breasts the hate or love which their financial necessities dictated, and those more highly wrought considerations of the intellect-justice, democracy, the golden rule, the respect for property, for constituted authority, the ideal of patriotism, etc.-those seem to have given way as though they were a little too fragile for service in a time of blood.

“I’m neutral,” said Dr. Jaffa to me, “I take no sides. But this thing has spoiled my business. What do they want to inflict it on us townspeople for? Look at the merchants along here. Look at the saloon-keepers. They’ve had to close up their doors. They can’t make enough to buy a coat! I just wish I was President of the United States for about ten minutes!”

Dr. Jaffa is a physician for the mining companies, and it is relevant to explain that one of the demands of the striking miners is for the right to choose their own physician.

“What would you do in that ten minutes?” I asked him.

“I tell you I’d do something! I might get hung for it, but I would find a way to get rid of these agitators who come in here and start all this trouble.”

“But,” I said, “I thought the trouble started long before that, when the mine owners brought in detectives to spot union men for discharge from the mines?”

“Now, it’s just this way! If I’m running a business-if you’re running a business, you aren’t going to have other people step in and tell you how to run it. Why, Osgood, the President of the Victor American Company, told me if he had to beg on the street he’d never have dealings with a union.”

“But look at it this way, doctor. Suppose the business you were trying to run happened to be the organizing of a union, you wouldn’t want somebody to tell you how to run that either, would you?”

“Oh, I suppose there’s right on every side,” he answered. “I’m neutral. But I want to tell you if General Chase had been given a free hand down here there wouldn’t be any strike now. He’d have said to these people that don’t want to work, ‘If you don’t like the work here, all right, beat it! Anybody who stays around here, works see?”

Dr. Jaffa, acting as a health officer on the field of Ludlow, had a flag of truce shot out of his hand by the mine guards and militia–but still he is loyal to the side he serves.

It seems that just one branch of republican “officialdom” in that town has resisted the bribe of class interest, and stood for the whole people; that is the public school. I gathered that a majority of the teachers were personally against the men on strike, but as teachers they were forbidden to mention the subject at all. The children were forbidden to discuss it. “Otherwise we couldn’t have kept school,” one of the teachers explained to me, and I judge he was right.

“You don’t see any fellas come around a girl,” I was informed by an authority of fourteen summers, “that the girl don’t know which side they’re on!” And that is the attitude of her big sisters. Perhaps in time, if the strike lasts long enough, intermarriages may occur!

Beyond the public schools, I could find no institution and no official of all that “democratic government,” upon whom one would rely to represent the “common interests” of the citizens. The local executives had been so confessedly partisan that when the miners flocked into the streets of Trinidad armed, after the massacre at Ludlow, the Mayor discreetly fled the city and the police went home to bed. Persons appealed for protection to the union headquarters. The county jail was full of strikers, imprisoned without charge or warrant, carried to prison in the automobiles of their employers, and denied even the rights that officialdom has professed to defend since the days of Magna Charta. The county sheriff, who had sworn in 594 “special deputies” in six months, also fled the city at the approach of the miners. Nothing more need be said of him. The coroner is an undertaker under contract with the mining companies for the burial of dead miners an incident whose gloom is not relieved by the report that the general manager of the company holds stock in the undertaking establishment.

As for the State of Colorado, and the legislative, executive, and military arms thereof, enough has been printed in the popular press to discover its class character to the blindest. That non-resident gunmen on the payroll of the mine companies were at the same time on the public payroll and clothed in a public uniform as soldiers of the commonwealth, is not an incident, but a summary of the whole situation in politics.

In what is called religion the alignment was more equivocal. A sweating effort at neutrality was made by the Jesuit priesthood of the Catholic church, an effort that always will be made, I suppose, in times of class crisis by the Catholic church. For the Catholic church is the Church of the Exploitation of the Poor, and it has its own gentle and peculiar mode of exploiting the poor and cannot afford to forsake them to others. The Catholic church has taken under her generously unprincipled wing every movement of history that she perceived to be inevitable, and you will hear her clucking to the Socialists yet.

In this struggle, however, it was only after a severe lesson that she perceived just where the inevitability lay. I was told by three or four different people that a Catholic priest had been virtually mobbed by the miners for preaching submission, and that he had hastened home in shreds and tatters of his dignity, and was put to bed by the priesthood. A Catholic father, however, told me that this misfortune occurred in another county and during a different strike. His account of what happened in the present strike I quote as he gave it.

“Every morning that I woke up in my bed,” he had said, describing the eight days after Ludlow, “I thanked the good God that we were alive!”

“And what is it all coming to?” I asked him.

“Civil war,” he answered, “war between labor and capital.’ “And the church, can the church do nothing to save us from this?”

“Absolutely nothing!” he said. “If the people had faith, yes! But when they run and report the priest himself as a scab-Oh! Why, one of our brotherhood went among the strikers preaching the salvation of their souls. ‘Idleness is the root of evil’-that was his text, and they reported him to the union headquarters and he had to stop preaching. “Shut him up!’ said the Superior to me, ‘Shut him up. Don’t let him speak a word!’”

This was amusing, and my friend laughed, as a man will who loves life better than his faith. He had learned his lesson well, too. He talked to me for a full hour, with the ease and freedom of a life- long candor, and yet never a syllable of his true feeling–except that childlike enjoyment of the humor of the situation–escaped him.

Of the seven Protestant ministers, five are hot little prophets of privilege. The other two feel that among the original causes of the trouble was the failure of the church to live up to her mission of teaching Christianity and other blessings of civilization to the miners. Just what Christianity would have done to the miners, unless it sent them back to work in the blessedness of the meek, was not explained by these ministers. But the Salvation Army leader made it perfectly plain that he considered the “preaching of contentment” to be his function in the mining camps. The gospel according to Marx!

The fate and feeling of the middle-class uplift-worker in such a crisis is quite according to Marx also. About the time that war was to be declared, or a little before, she went to Walsenburg with a charitable friend, feeling sore at heart that the miners’ boys had no place to lean and loaf but at the bar of the village saloon. With the sanction of the mine-owners, and being herself the wife of an editor in good standing with the companies, she essayed to start a recreation center. Visiting all the mothers in the mining camp she invited them to attend a conference upon the subject in a public hall.

“And how many women do you suppose came to that hall?” she exclaimed. “Just two-myself and the woman I took with me!” “I tell you,” she cried, “they are not only brutal and ignorant, but they are satisfied! They don’t want anything better. They are nothing but cattle.”

In this opinion that “they are nothing but cattle,” she merely gave the countersign, as far as I could make out, which admits to social recognition in Trinidad. I have described in the Masses a tea-party I enjoyed with Trinidad’s nicest ladies, but I want to quote here just one further sentiment upon which they agreed.

“Are there not a good many Jewish people in Trinidad?” I said. “Yes, and the Jews have stood with the Christians right through!” said a mine owner’s wife. “Mighty fine folks all of them!”

When the NEW REVIEW arrives upon the heights to which it is destined, I trust we may establish in connection with it a bureau of economic research. It would be worth much to revolutionary science, I think, to send a census-taker to a place like Trinidad, ascertain the alignment of classes and professions, the conduct and state-of-mind of persons and institutions in such a war. A little more verification, a little less assertion, would be so much to the health of the Socialist hypothesis. And these notes of mine, I am aware, have little value other than to suggest such a possibility.

It is needless to say that the newspapers stood at sword’s point–the two prosperous and established papers with Associated Press wires, “fighting the mine-owners’ fight from the very start,” and “getting information only from that side,” as one of their editors informed me, and the other paper flirting for a time with the cause of the miners, until finally it was leased and operated by the union. Nor was this antagonism confined to the editorial office, or even the press-rooms. The newsboys on the street were divided into two armies, and it was only by pressure of special friendship that a Free Press newsboy would call an Advertiser newsboy if it happened to be the Advertiser you asked for.

The tradesmen, the smaller ones especially, who rely for profit upon pay-day expeditions from the mining-camps, were with the strikers. They were so whole-heartedly with the strikers after Ludlow, indeed, as to convey an impression that the whole city had opened its doors to receive them. Miners told me that ninety per cent. of the citizens welcomed them. But mine-owners told me that anybody who did not welcome them thought best either to stay at home or pretend that he did, and for that reason even a guess at the true percentage is impossible.

The demi-monde, while professionally neutral, is by natural sympathy tender to the union. The small farmers in the vicinity of Ludlow sheltered the strikers after the massacre, and fed them–for which service at least one ranch house was wrecked and looted at midnight by the militia, and a significant warning left on the wall:

“This is your pay for harboring union men and women. Cut it out or we call again.

“B.F.

“C.N.G.”

The initials mean Baldwin-Feltz and Colorado National Guard. We must not be too hopeful, however, upon the basis of these facts in Colorado. It is not a revolutionary strike. It is not a strike against capitalism but against feudalism. Moreover, the feudal lords are perpetual absentees; their pecuniary prowess is never displayed locally where it might awe the middle class into a consciousness of its beauty and divine right. And moreover, again, the methods of these absentee lords have been startling in their brutality, and the miners have been startling in their patient persistence and good nature. Therefore all those whose interests were not strongly engaged upon the one side or the other, being creatures of human blood, fell in unanimously with the injured. To quell a fight for liberty with unprovoked persecution, is to quench burning oil with water. That is, it only spreads the blaze.

For these reasons we cannot infer all that we might wish to from the Colorado alignment. But we can rejoice in a great many things not least of which is the fact that some of those smooth delegates of the A. F. of L. that we call Labor Fakirs, folded their papers in this crisis, loaded up with shot and shell, and went out into the hills to do business. Revolutionary or not, the working class of Colorado were of one mind and one intention for the space of eight days at least!

Railroad men have been unanimous from the very off go, conductors and all. Even last fall, before any cold-blooded killing or any massacres had occurred, the trainmen stepped off their trains and refused to carry reinforcements to the militia at Ludlow.

“They allowed they were afraid to go where the shooting was in progress,” a brakeman told me, “but that’s merely a way of speaking, you understand. There was plenty of ’em shouldered a gun and went out there with the miners.”

The train load of reinforcements, he added, was taken out by the division superintendent and the train-despatcher, and the men who deserted were of course discharged. In the first case the union gave the company three days to reinstate them, and the company reinstated them on the third day. In the second case, after the massacre at Ludlow, the company reinstated the men within two days without need of a warning. When you realize the close subservience of the Colorado and Southern Railroad to the mines that feed it, you see that a significant little bloodless battle of the war was fought during those three days, and that labor was victorious.

But, however significant or not significant to the Marxian economist, the alignment in Colorado can certainly prove a strong point to the layman. It can prove that when the class line is once fightingly drawn, all other divisions of society sink into obscurity, and every man, woman, and child is compelled to take a militant stand. I suppose the line between mining capital and mining labor passed through the very middle of some people’s lives. They had interests both ways. But they were forced to move. You cannot stand on a red-hot line.

Perhaps the most earnest effort to do so, the warmest approach to sympathetic neutrality, was made by the sisters of charity at the San Rafael hospital, nurses who stanched the blood for militia and miners alike. I talked with the leading sister of the order there, a gentle, vigorous and serene soul, with memories of the civil war, a woman who could mother both sides of a fight if anybody could. “We have no opinion,” she said, “we are for all men.”

“I know you have no opinion,” I answered, “but I wonder if you wouldn’t just tell me what your opinion is!”

“Even in our minds,” she said, “we form no opinion. But I can tell you that this has been a very terrible thing, and I am praying every night that they will recognize the union so that we may have peace!”

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1914/v2n07-jul-1914.pdf