A valuable explanation of the organs of power in the Soviet state as established by the 1918 Constitution and developed in the first years of the Revolution. In six parts: I. The All-Russian Central Executive Committee, II. The Council of People’s Commissars, III. The Council of Labor and Defence, IV. The All-Russian Congress of Soviets, V. Local Soviet Congresses, VI. Town Soviets.

‘How the Soviet Government Works II: Council of People’s Commissars’ from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 6. No. 2. February 1, 1922.

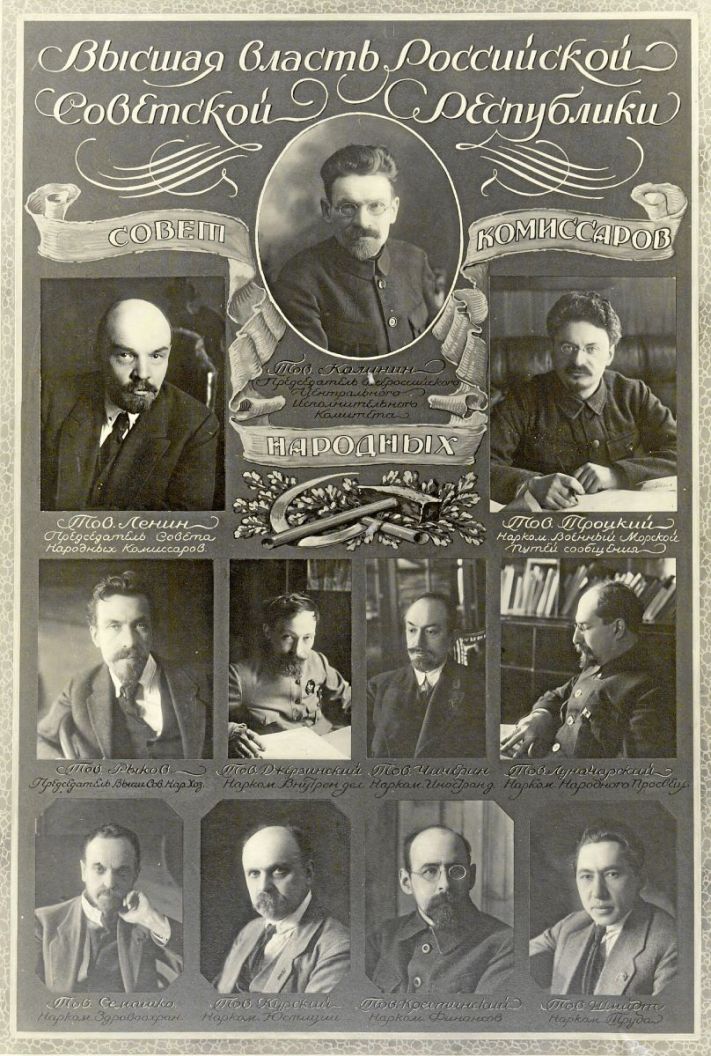

THE Council of People’s Commissars is that section of the apparatus of Government which concentrates in its hands from day to day all Government authority for purposes of current problems of administration. It is the Cabinet of the Soviet constitutional machine; and in its resemblance to the Cabinets of other political forms represents the nearest approach made by the Soviet constitution to the forms which have preceded it.

The supreme executive authority—and in Russia today it is very rare that the executive authority undertakes to legislate on important points without previously raising the matter in the supreme organ of all authority, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee—cannot be bound in its inner working by formal regulations, rules of procedure, etc., which must inevitably be drawn up in the case of a body which unites the executive with other functions. A weekly or bi-weekly meeting of eighteen or nineteen heads of the principal administrative departments of State, who come together primarily not to legislate but to solve those of the problems which have arisen in the working of their departments which affect other sides of the national life —such meetings will be found at the head of the constitutional machinery of any modern community. If the Council of People’s Commissars is in any way different from the Cabinets of western countries, it is perhaps in the actual make-up— the education and social outlook — of the men within it; possibly also in the existence of one or two departments of State which are not found in political structures based on a different social order.

In the case of the Soviet Cabinet, moreover, the restriction of its functions to the framework laid down by the Soviet constitution of July, 1918, “the general direction of the affairs of the Republic,” is made more marked by a number of peculiar features.

Each individual People’s Commissar is the head of a department, the care for which was entrusted to him by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee or the All-Russian Congress of Soviets; but he is responsible not only to these bodies, but also to a board, which exists in each People’s Commissariat, and with which each People’s Commissar must consult on all questions, with the exception of urgent cases. The board, moreover, without interfering with the execution of any decision of the People’s Commissar concerned, has the right of bringing the question at issue before the whole of the Council of People’s Commissars, at one of its regular sessions. It is very rare, in point of fact, that a session of the latter has taken place during the last few years without any members of the board (in which are included the assistant People’s Commissars) being present.

The constitution of July, 1918, laid down that the All-Russian Central Executive Committee has the right to annul or suspend any decision or order of the Council of People’s Commissars. An amendment adopted by the Eighth All-Russian Congress of Soviets in December, 1920, permits the presidium of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee to exercise this right also, both as regards individual Commissariats and with reference to decisions of the Council of People’s Commissars as a whole.

These decisions have now for nearly four years been issued in one uniform way, over the signature of the Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, as representing the whole body: and of the Administrator of the Chancery and the Secretary to the Council of People’s Commissars, as technical confirmation that the published decree corresponds exactly to the original adopted at the session of the Council This practice has taken the place of the heterogeneous and unsystematic forms prevalent during the first months of the revolution, when sometimes several People’s Commissars signed a decree and sometimes only one. Only decrees and national proclamations of exceptional importance—such as announcements of a national crisis—are now signed by more than one People’s Commissar; while a decision published over the signature of one People’s Commissar alone, not the chairman, means that the announcement in question is of the nature of an administrative regulation, and not a decree affecting the mass of citizens.

All decrees of the Council, and all regulations issued by its members individually, are binding upon the central and local authorities whose work they affect. The transmission of these dispositions takes place in two ways; to the principal local authorities (Soviet executive committees in provinces, counties, and rural districts, and Soviets in towns and villages), where the matter involved is one of general importance, and involving the work of more than one department (for example, a decree instituting a three weeks’ “fuel campaign”, a decree instituting a ten per cent tax on all theatre, concert, etc., tickets in aid of the Famine Relief Fund, or a decree instituting a network of brigade political schools of instruction for the needs of the Red Territorial Army); and direct to the local departments themselves (health, education, labor, general administration, etc.) where the question is one of detailing or explaining the work of the People’s Commissariat concerned to its corresponding department of the local authority (for example, where it is a question of organizing mutual aid committees in the villages and rural districts under the auspices of the county social welfare departments, or of registration of the stocks and inventories of Soviet estates by provincial land departments, or of explaining to the local economic councils the policy of the Soviet Government with regard to the leasing of factories).

Decrees by Individual Commissariats

Once transmitted, as has been pointed out, the decree or regulation is binding; but the amendments to the Constitution adopted in December, 1920, provide for the suspension by provincial executive committees of decisions of individual People’s Commissariats, “in extraordinary circumstances, or when such disposition is in clear contravention of a decision of the Council of People’s Commissars or the А.R.C.E.C., or in other cases by resolution of a provincial executive committee.” In such cases, however, the latter must immediately inform the Presidium of the A.R.С.E.C., the Council of People’s Commissars, and the People’s Commissariat concerned; and it bears collective responsibility before the first-named body, which shall decide which party is at fault (if necessary, which party shall be impeached). That this amendment to the Constitution has not remained merely on paper has been shown by several striking cases, during the last twelve months, of impeachments before the Supreme Judicial Tribunal of local food departments, economic councils, departments of health, etc., for arbitrarily setting aside in one way or another the decisions of the central authority from which they receive instructions.

On the whole, however, striking irregularities in the execution of the decisions of the central authorities have been, wild and vague assertions during the past four years notwithstanding, surprisingly few, wherever local conditions did not completely prevent the transmission of those decisions in a clear and lucid form, or were not in some other way so abnormal as to distract public attention from the particular question involved. While, judging by customary standards, this is a surprising feature to encounter in a revolutionary administration, on the other hand it is perhaps as characteristic of the new methods and work heralded by the rise of this revolutionary administration as any other side of its activity. In the words of a recent writer: “Any politically-educated citizen knows that every decree of the Council of People’s Commissars, whether it deals with collective payment of the workers or with some reform in the army, is not merely the composition of some wise men in a Cabinet. Every decree is the outcome of a vast preliminary work at working-class meetings, in factory committees, in Soviets, trade unions, party organizations, peasant and Red Army assemblies, economic conferences, and so on. If anyone were to undertake the task of tracing the history of some important decree, he would receive convincing evidence of how its main points, first in the shape of vague expressions of desire, and then in more or less definite resolutions, took shape amongst the active rank and file of the class-conscious masses. And very soon, passing through the stages of party, trade union, and Soviet discussion, they reach the centre, where they receive their final form in the shape of a new law.”

Quantity of Work Done

When we turn to the few but illuminating statistics we have at our disposal to illustrate the work of the Council of People’s Commissars, it becomes difficult to decide at what to be more astonished —at the activity of the masses, to which reference has just been made, or to the immense capacity for toil of the men at the other end of the constitutional machine. During the six months between November 1, 1920, and May 1, 1921, 395 questions came up before the Council of People’s Commissars, of which fifty-seven were brought forward by the Supreme Economic Council, forty-one by the Sub-Council (a special commission of the Council, set up during the last twelve months, for the purpose of dealing preliminarily with numbers of questions, principally of an economic character, thereby facilitating the work of the larger body), thirty-four by the People’s Commissariat for Food, twenty-six by the Commissariat for Foreign Trade, twenty-five by the Commissariat for Land, twenty-three by the Commissariat for Agriculture, and so on. It is noteworthy that, in all, seventy per cent of the questions discussed were of an economic character. Similarly, out of the 1,178 questions that came up for discussion during the indicated period in the Sub-Council, 385 dealt with finance, 153 with questions of Soviet organization, 180 with questions of industry, 105 with questions of labor; and so on, military, judicial, and even educational problems being overshadowed by economic problems. Thus, the Council of People’s Commissars at work is a true reflector of the life and needs of the nation at the present moment of transition. The thirty commissions of the Council which were organized during the first four months of 1921 fall into categories which point the same moral. Seven were on industrial questions, seven on questions of supply, four for working out points in connection with labor and compulsory labor service, two on financial questions, two on general questions (the drawing up of a draft sketch of the activity of the economic commissariats, and the organization of a State Economic Planning Commission), and eight in connection with other о These commissions are thus in marked distinction from those set up under the auspices of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, the functions of which, as indicated in an earlier article, are bound up first and foremost with questions of control, and then with questions of law.

The Council of People’s Commissars, therefore, is the centre at which the nineteen People’s Commissariats meet for harmonizing their activity, settling questions of an inter-departmental character, and working out legislation for submission to the chief legislative authorities in connection with those (principally economic) problems, the solution of which is vital to the existence of the Republic.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v6-7-soviet-russia%20Jan-Dec%201922.pdf