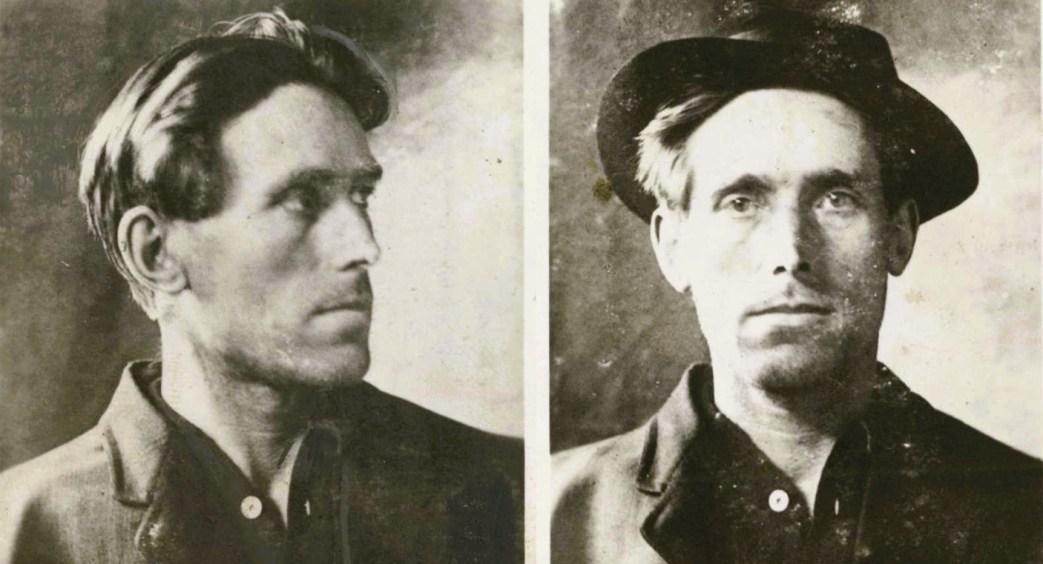

Invaluable personal recollections and moving estimates of Joseph Hillstrom from his comrade Ralph Chaplin.

‘Joe Hill, a Biography’ by Ralph Chaplin from Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 1 No. 7. November, 1923.

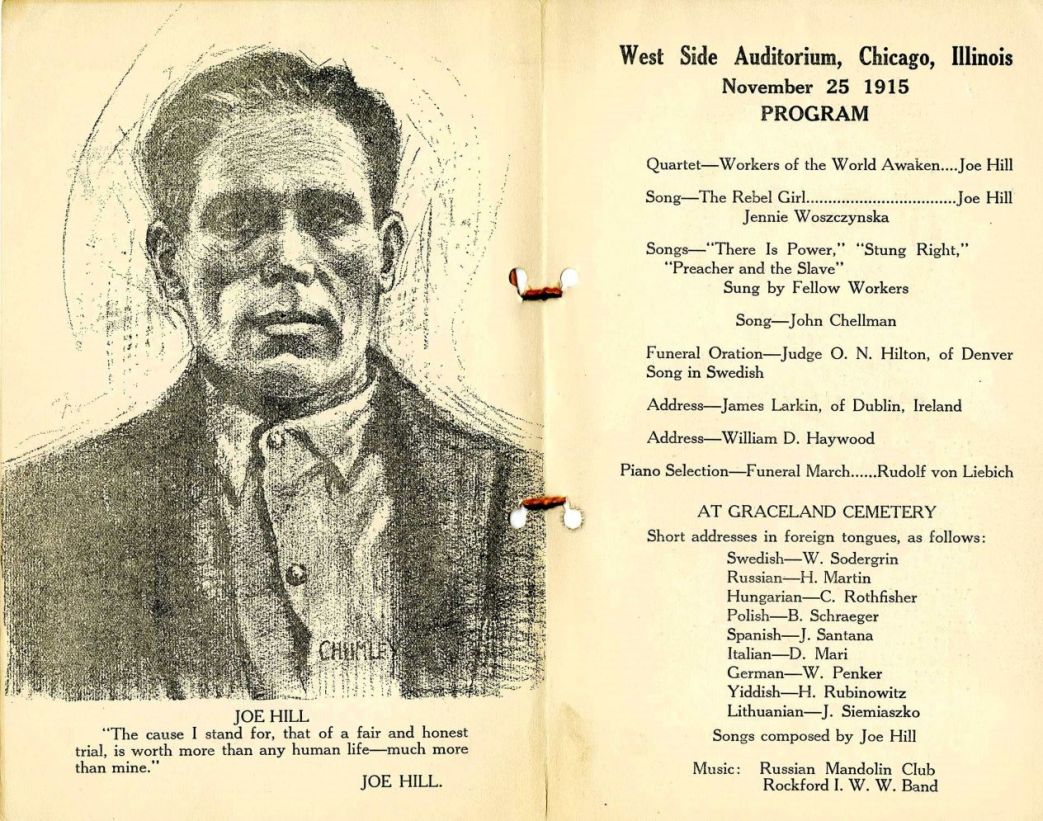

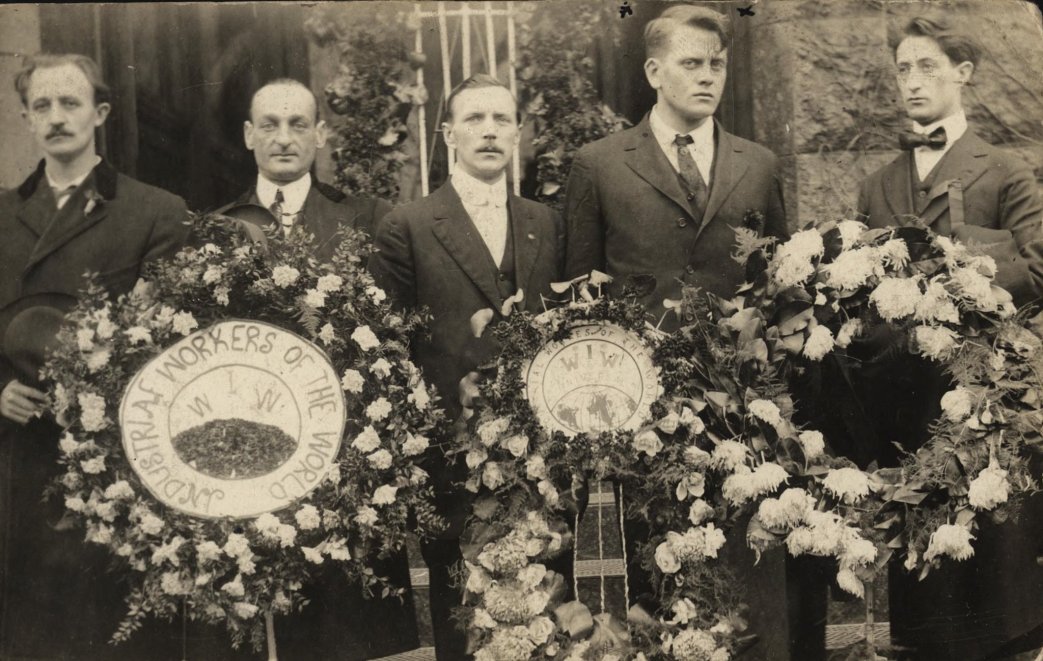

JOE HILL’S funeral took place in Chicago in 1915. Fellow workers who attended this funeral—historical in the annals of the labor movement— will remember the amazement and horror with which good citizens contemplated the magnitude of the event. As a rule when persons prominent in public life pass away, persons distinguished and honored by the capitalist system for services rendered, their funeral services are impressive also, but only after a perfunctory and formal fashion. Other distinguished and honored persons assemble to pay homage to their departed fellow. Curious crowds look on with more or less indifference, the hearts of very few are really touched and the affair is soon forgotten.

But when the bullet-riddled body of Labor’s Songster was placed at rest the outpouring of the people was spontaneous and unprecedented and the grief truly genuine. The funeral procession itself was miles in length and it took hundreds of men and women to carry the furled banners and the floral offerings. It seemed that the entire working population of Chicago had turned out for the occasion. The streets were black with spectators and all traffic was suspended.

Naturally the good citizens were astonished,—the more so because Joe Hill was a common migratory worker who, far from being respectable, had been shot to death as a felon by the respectable, distinguished and honored authorities of the State of Utah. How could people be expected to understand?

What Kind of Man Is This?

While the endless throngs of workers were pouring into the undertaking rooms of the West Side Auditorium to pay their last respects to the mortal remains of Joe Hill, one of Chicago’s biggest newspapers asked editorially and with genuine surprise, “What kind of man is this whose death is celebrated with songs of revolt and who has at his bier more mourners than any prince or potentate?”

The “Songs of Rebellion’ were Joe Hill’s own songs—the valiant, deathless and unconquerable part of him that continued to live and to battle after the body had crumbled to dust. And such songs they are! As coarse as home-spun and as fine as silk; full of lilting laughter and keen-edged satire; full of fine rage and finer tenderness; simple, forceful and sublime songs; songs of and for the worker, written in the only language he can understand and set to the music of Joe Hill’s own heart.

It is not generally known that Joe Hill was on his way to Chicago when he got into the trouble in Utah that cost him his life. Little did he, or anyone else dream that when Joe Hill started on this journey he would reach his destination in a white casket case covered with carnations and draped with red ribbons. But such is the case. Joe Hill had been in Chicago on a previous occasion, in 1903, shortly after his arrival in the United States. It was here that he earned the stake which first enabled him to travel on to California—and to his destiny.

Born in Sweden

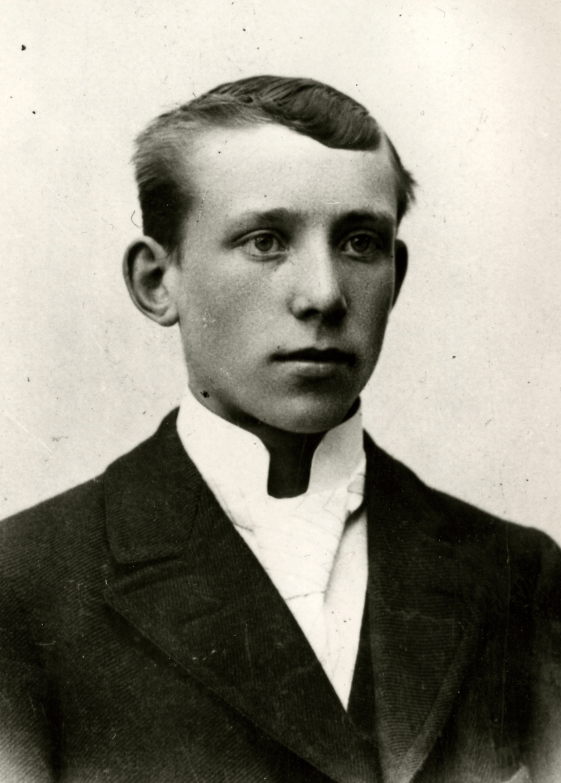

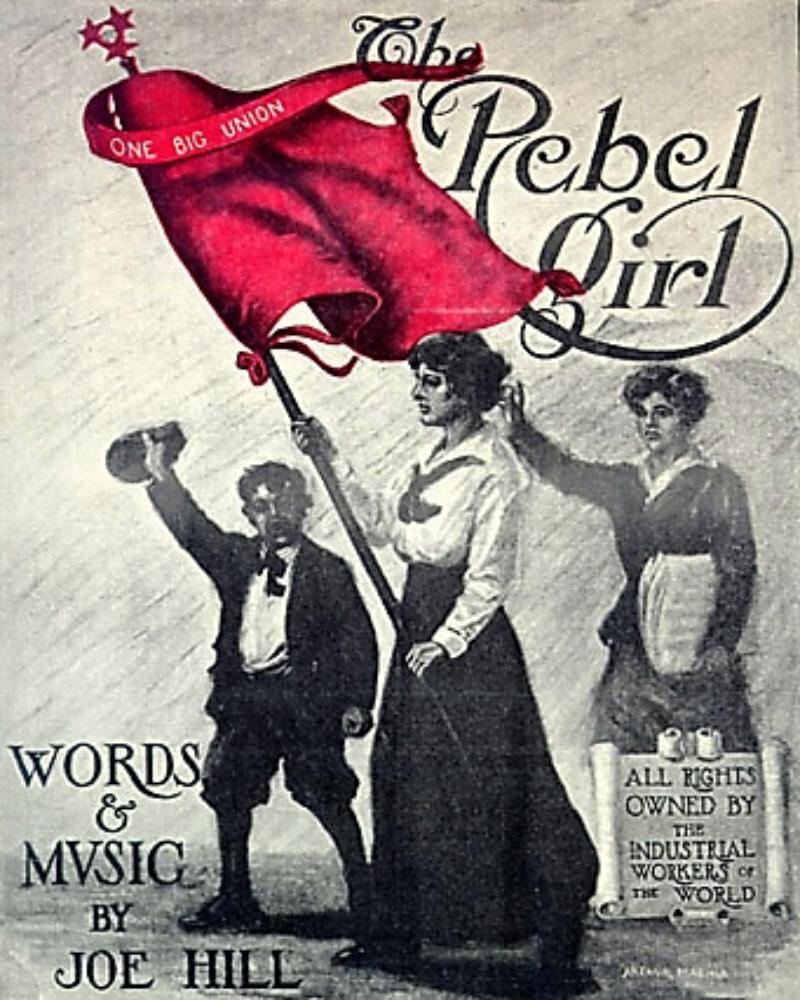

Joe Hill’s full name is Joseph Hillstrom. He was born in 1882 in the little town of Jevla, Sweden, in the province of Gestrickland. His education was no better and no worse than that of other boys in his neighborhood. He went to the public schools until he was sixteen. Only Joe Hill must have been different. He was a born rebel and a born artist. The passion of his life, apart from the revolution, was for poetry, music and drawing. And it isn’t fair to say, “apart from the revolution” either, for Joe Hill’s work in these lines was a part—and a big part—of his fight against capitalism. Even in prison just before his execution he wrote the words and music for such songs as, “Workers of the World Awaken,” and “Don’t Take My Papa Away From Me.” The cover designs as they are now used were taken from his own drawings made in the death cell. Joe Hill had a considerable talent for drawing and whiled away many tedious hours in prison sketching objects of his interest or his imagination.

Joe Hill learned to speak English while working on the boats between Sweden and England. He improved his knowledge by studying English grammar at the YMCA night school in Gottenburg. Before becoming a sailor he had worked as a fireman on the National Railroads of Sweden.

Death of Mother

Joe Hill left his native country because of the death of his mother. Just what this tragic event meant to him no one perhaps will ever know. He is said to have inherited his talent from her and to have loved her greatly. This circumstance and the innate restlessness of his Viking blood brought him to the city of New York in the spring of 1902. At this time he was a tall and eager-faced lad of twenty summers. No doubt he had heard much of America, the land of freedom and opportunity. He was broke and a stranger. His only acquaintance was his cousin, John Holland, who had journeyed with him from Sweden. The two worked at odd jobs wherever employment could be found. Joe Hill even worked for two weeks as a porter in a Bowery saloon. Naturally he didn’t like the strange new world in which he found himself. Perhaps he thought that by some mischance he had struck the wrong part of the fabled land of opportunity—that by going a little further west everything would be different. At all events, after having slaved in New York for a year, Joe Hill and his cousin left New York for Chicago. Here the adventure was repeated all over again. Odd jobs, hard thankless labor and constant uncertainty. Eight weeks of this was all they could stand. A two week job in a machine shop on the North side gave Joe a twenty dollar stake. With this the two boys again started westward. By this time they had learned to travel further on their money. After many adventures the Twenty-four pair finally met in San Pedro, California. Here they lived for a little more than three years camping or “batching it” in their own shack. Joe Hill made friends from the beginning. Most of his work was done on the longshore. There were other jobs, too, but he seems to have liked the longshore best. The call of the sea troubled Joe Hill’s Viking blood now and then. When he could stand it no longer he would ship out on a boat to Honolulu, Alaska or the west coast ports. His Best Friend

The best friend Joe Hill had in San Pedro was a man named Macon in charge of a mission at 331 Beacon Street. This Mr. Macon liked Joe and was very good to him. There is no doubt but Joe Hill appreciated Mr. Macon’s friendship and reciprocated it, but it was the piano that was the chief attraction. Joe was a brilliant pianist and enjoyed greatly playing both for his own amusement and the entertainment of his friends. But Joe used the mission piano for another purpose. He would strum out well known tunes lightly with his nimble fingers, improvising new words as he went along. Every one within hearing distance would come under the spell of the humor of his parodies and his infectious smile as he worked them out a verse at a time. The idea of saving these little skits or writing them down never seemed to have entered Joe Hill’s head. He just dashed them off on the spur of the moment and then proceeded to forget them. But the people who heard them could not forget.

Joe Hill was well liked in San Pedro. The longshoremen with whom he worked liked him because he was the first man on the job to speak out to the boss when conditions were not right. Oftentimes he was the last to leave the job when a strike was on but he always brought the crew off when he left. This was before he joined the IWW. He had all the requirements of a first class agitator and had already studied dozens of books on the labor movement.

Lover of World-Music

In the shack where he and his cousin lived he was equally popular. According to John Holland, Joe knew “‘all the music in the world and could play any civilized musical instrument.” He was also an adept in the art of oriental cooking and could prepare Chinese dishes to delight the most exacting visitor. He could use chop sticks like a native. When times were good the latch-string was always out; when times were hard it was always out anyhow. Frequently he would give away to a passing stranger the last mouthful of rice in the little shack, many times himself going without in order to do so.

Writes Casey Jones

The Southern Pacific strike came along about this time and it was this strike that made Joe Hill famous as a song writer. Casey Jones, as it appears in the little red song book, had been strummed out on the mission piano to the hilarious delight of a few striking railroad men who were present. The strikers urged him to write down the words and to have them printed on a card to be sold for the benefit of the striking railroad men. This was done and Joe Hill’s version of Casey Jones became immediately famous in the west. Migratory workers and strikers carried it to the far corners of the land. But Joe Hill immediately proceeded to forget it as he had the others. He was greatly surprised when a theatrical troupe hit town shortly afterwards which used his song as one of their chief features.

Joins I.W.W.

Among those who had heard the song was Fellow Worker Miller, at that time secretary of the San Pedro local. Fellow Worker Miller made it his business to look up the author of Casey Jones and to invite him to become a member of the Industrial Workers of the World. Both Joe and his cousin were glad to join. They became active without delay. This was in 1910. Joe never transferred from the San Pedro local. He wore his first button on his breast at the time he was cremated in Chicago.

Joe Hill became popular in the IWW at once, not only as a song writer and entertainer but also as a rebel. It was in the IWW that he found his fullest and freest expression. He was intensely active at all times, working unceasingly either on the job or at home writing poems. His mind was never idle a moment. Even during the rest hour he would dream away for a little while and then jot down his inspiration in lines and verses as they came to him. These he would polish up at night until he got them to suit him.

Not A Rounder

Unlike his cousin and many of his friends Joe Hill was not a man of the world. Many times Holland would say, “Come on, Joe, let’s go and have a good time.” The invariable answer was, “Can’t do it; too busy.”’ Holland said he always found Joe busily engaged in writing verses when he returned home— no matter how late the hour. Joe had a way of twisting the hair on his forehead as he leaned over the lamp-lit table puzzling out the rhymes for his songs. Joe was always very courteous to girls and women but he never went out of his way to seek the company of the fair sex. Arturo Giovanitti, in one of his best and least known works, a drama founded on the case of Joe Hill, brings out a very plausible theory that the IWW song writer permitted himself to be executed rather than betray the honor of a woman. If Joe Hill ever met the right woman he would be the kind of man to do this very thing. It is unlikely now that anyone will ever know the truth. The bullet wound in his hand that led to his arrest and conviction is still a mystery. Joe Hill carried the secret of it to his grave. Giovanitti’s masterful drama is a valuable contribution to the literature of the IWW and the world. It could be used to good advantage for the defense by fellow workers all over the country. It is infinitely superior to any drama the IWW or other revolutionary organizations in America have yet produced.

Never An Idler

But Joe Hill, as far as can be known was not a ladies’ man and he never had a “steady girl’ in all his life. If he loved at all it was not a light love by any means. He would care for a woman as he did everything else, intensely and with all his heart.

Joe hill was never an idler. He worked hard and wrote and labored for the organization incessantly. He is a man who never smoked in his life nor drank intoxicating liquor. His record in the IWW was splendid. He kept his dues paid up and was one of the very first to urge carrying organization propaganda from the soap box to the job. He was in the Fresno and San Diego free speech fights. At the battle of Tia Juana he was shot through the leg by a Mexican regular and only reached the border after the greatest of difficulties.

Joe Hill lived in San Pedro over three years all told. He finally left there to come to Chicago, for what purpose no one knows. While on his way, for some reason or other, he wanted to go to Los Angeles. It seems his purpose in doing this was to locate an old boyhood friend whom rumor had placed in that city, sick, and in a hospital. This friend’s name was West, or Westergren. He also had been born in Jevla. Joe was however unable to locate his friend in Los Angeles. So he started again for Chicago. On his way he stopped off at Salt Lake City. His purpose, as he stated to his cousin in a letter, was to see a distant relative by the name of Mohn.

Victim of Copper Trust

The story of Joe Hill’s arrest, conviction and execution before a firing squad in the penitentiary in Salt Lake City is too well known to need recounting here. He had been in Utah only about a month, most of which time he had been working and organizing in Bingham Canyon. His efforts for the organization in this notorious slave pen had won him the implacable enmity of the Copper Trust. His murder was instigated by the same red-handed bunch of industrial highbinders that murdered Frank Little —and for the same reason. His execution took place at sunrise on November the 11th, 1915. He was game to the last and gave the order for the volley that caused his death.

Joe Hill never mentioned his cousin at the trial, possibly for fear of causing his arrest as an accomplice in the alleged crime. Holland was active at this time in the strike at Prince Rupert—a member of the strike committee there, in fact. Joe claimed he had no relatives alive but it is thought he had a brother in Sweden. His father and mother were both dead before he left for America.

Not Guilty

Joe Hill sent a note to his old friend, Charles Rutberg, mate of a steamer on which he used to work. “I am not guilty,” is what it said. This is at present the verdict, of the entire world. There is no doubt at all that Joe Hill was the victim of a capitalist frame-up.

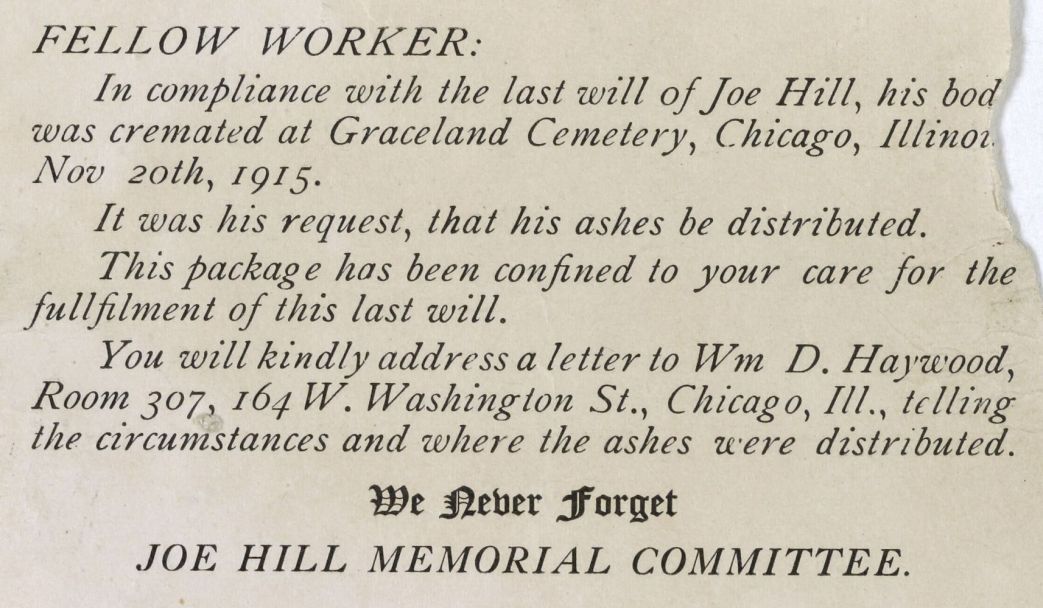

His body was cremated at Graceland cemetery in Chicago. The ashes were sent to IWW branches in all parts of the world. This was done in keeping with his last wish that flowers might grow where the ashes fell. So much for his body. But his songs have gained a wider audience than any similar songs written in any language. These songs are being sung by more workers today than ever before. They are rebel songs, true songs still warm with the blood of the brave young heart that was torn with lead of the Copper Trust executioners in 1915.

His last words were these, ‘‘Don’t mourn for me; organize.’ I wonder if it is true that “we never forget’?

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrial-pioneer/Industrial%20Pioneer%20(November%201923).pdf