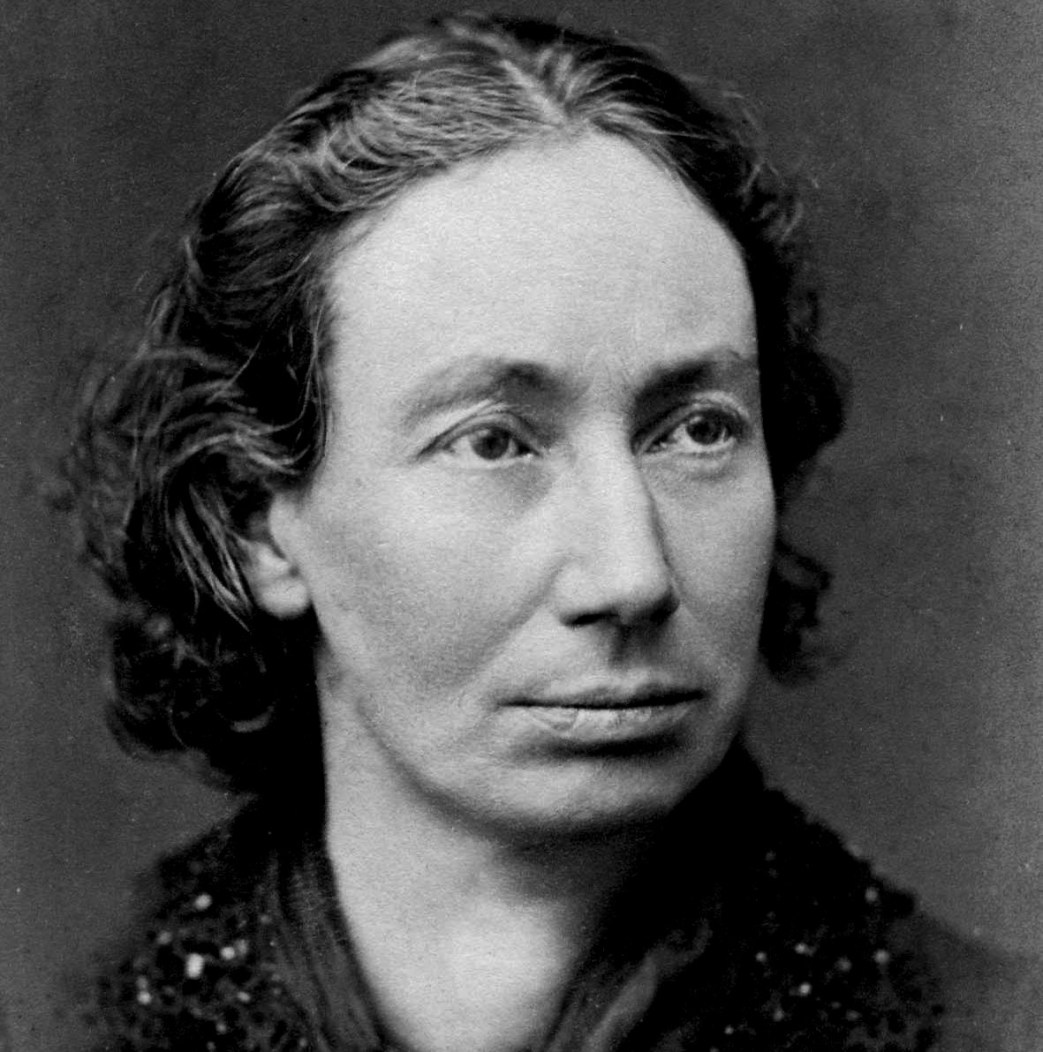

Sasha Small on the exemplary leader of the Paris Commune, Louise Michel.

‘Louise Michel’ by Sasha Small from Working Woman. Vol. 5 No. 2. February, 1934.

A story of women in the Paris Commune. The women, led by Louise Michel, fought bravely on the barricades in the streets of Paris for a Workers’ Government–for a better world.

“The proclamation of the Commune was splendid. It was not the fete of power–it was the pomp of sacrifice. One felt that the newly elected Commune was willing to die for its principles…A sea of people under arms, bayonets crowded together like ears of corn in a field, trumpets rending the air, muffled beating of drum…The heavy roaring of cannon saluted the revolution at regular intervals. Bayonets were lowered before the red flags that were draped about the statue of the Republic…All of Paris is out. The Central Committee is on the platform. Before them stand the members of the Commune, all wearing Red sashes. The Central Committee declares that its mandate has expired. It hands over its powers to the Commune. There is a roll call. A great cry is lifted: ‘Vive La Commune.’ The drummers beat their drums. The artillery shakes the sun. ‘In the name of the people the Commune is proclaimed.'” (From Louise Michel’s book “La Commune”)

In the ranks of one of these regiments drawn up before the Hotel de Ville, her heart beating with triumph and hope, stood a young woman. Small, slight and not beautiful. For she had worked endless hours among weeks and months before this day the working women on Montmarte, in Bellville, and other working class neighborhoods of Paris, organizing them into Vigilance Committees, teaching them, talking to them, awakening them to class conscious ness. Her name was Louise Michel.

She was born in a small French village in the early 30’s of the last century. The exact date is not known for she was the illegitimate daughter of a peasant girl and the son of the nobleman who owned the village. Her grandfather was a liberal man who brought the child up in the ruined old castle. He was a Republican, a firm believer in the principles of the French revolution and a great hater of monarchy. He gave Louise a fine education.

She came to Paris in 1856–Paris at the height of the Second Empire. The shameless luxury of the ruling classes was flaunted in the face of the misery of the masses. Corruption and scandal flourished in the open. Freedom of thought and expression was not even the dishonest phrase that it is today in our country. It was openly forbidden.

But the resistance against oppression was growing. Ideas of revolt and freedom were seeping through the barrier of darkness. Literature was smuggled around, lectures were held. And Louise Michel studied. After the fall of the Empire, defeated by the rising power of the Prussian ruling class in September 1870, political clubs sprang up over night. Vigilance committees were organized. The workers were thirsty for knowledge after 20 years of repression. Their energy and rebellion reached a fever pitch. The Vigilance Committees formulated immediate demands, which they presented to the new government–a republic that continued the same exploitation and crushing of the workers behind radical phrases, as the Empire had carried on in the open.

Louise Michel was the driving force in many of these committees.

She led delegations of women to the City Hall. She wrote up their demands and sent them to the working-class press of that day.

And then on March 18th, the workers finally saw through the treachery of their republican government and revolted. The government leaders had been trying for months to disarm them, especially after they surrendered Paris to the Prussians. But the Parisian workers held on to their ammunition just as the Austrian workers did last month.

With the proclamation of the Commune Louise Michel’s activity doubled. She personifies the spirit of those 76 days of the Commune. To list her activities is to list the activities of the Commune, particularly of the Communard women. Women’s clubs were organized in the churches which were declared public property. A Union of Women was established, which took up the problems of arranging free schools and nurseries where mothers could leave their children while they went to work. It is hard to say what else they might have accomplished, because their work was soon interrupted. But this document shows their aims.

“April 20, 1871.-

“A true and solid organization has been formed among the citoyennes of Paris, resolved to sustain and support the cause of the people, the Revolution, and the Commune. It will aid the government commissions in their work and serve in the ambulances, common kitchens, and on the barricades.

“Article 1-The committees of each arrondissement are especially charged to: Register at once all citoyennes ready to serve with the ambulances, in the kitchens, or on the barricades.

“Be ready at any hour of the day or night according to the urgency of circumstances to call upon the registered citoyennes in the service of the State; this summons is to come from the Central Committee upon invitation from the commissions of the government.

“Central Committee of the Union of Women.

“Louise Michel.”

The last weeks of the Commune were spent entirely in defending it against the ever tightening circle of enemy fire.

When there seemed nothing left to do but to die fighting on the barricades Louise Michel dressed herself in the uniform of the National Guard, took a gun and fought until the last barricade was taken. At the same time she organized a nursing corps among the Communard women. Here is a letter, which she wrote on April 25, 1871, to one of the newspapers of the Commune, La Sociale: April 25, 1871. La Sociale.

“Comrade Editor:

“The volunteer nurses of the Commune come, in passing, to shake your hand. They ask you to insert the following declaration, for they feel, that in this moment, those who do not declare their stand, are just like those who flee, cowards.

“The ambulancières of Commune declare themselves bound to no other form of society than that which exists at the present moment. Their lives belong completely to the revolution. They are determined to nurse on the field of battle the wounds inflicted by the poisoned bullets of the Versaillese, to take gun in hand and fight be- side the others when the hour comes.

“Vive la Commune. Long live the Universal Republic.

“The volunteer ambulancieres of the Commune,

Louise Michel.”

By some miraculous chance Louise Michel was not killed on the barricades, where men, women and children died by the thousands defending their Commune–the first workers government in the world.

She was captured, taken prisoner and along with other thousands marched through the rain and mud for hours from Paris to Versailles. For seven months she remained in the filth and horror and Satory jail–filled with captured Communards where every thought was punctuated by the rattle of bullets shooting down into graves, they themselves were forced to dig, workers who had dared to establish a government of their own.

On December 16, 1871, she was brought to trial before the blood-thirstiest court of the reaction. She defended herself in a speech that was reprinted in newspapers all over the world–even in the American press.

“I will not defend myself and I will not be defended. I belong body and soul to the social revolution and I take, without restriction, entire responsibility for all my acts.

“I am told that I am guilty of having participated in the Commune. Of course, I am. The Commune strove towards the achievement of the social revolution and the social revolution is the most fervent of my hopes. I share all the ideas of my brothers in the Commune and I am ready to atone, just as they the did, for my convictions; Commune never murdered or stole! If there were assassinations or threats search for their authors among the police, among those who judge us. We wished for nothing but the triumph of the great principles of the revolution. I swear it by the blood of our martyrs whom I acclaim from this place and who will some day be avenged.

“What I demand of you who are soldiers and who are my judges, is that you do not hide behind the Commission of Par- dons. I demand of you the field of Satory where my brothers have already been killed. I must be removed from the world. The judge has already said so. Very well. This commissioner of the republic is right. As long as every heart that beats for freedom has no other right than to hold a piece of lead, I demand. my share too. If you let me live I shall not cease to shout for Vengeance upon the murderers of my brothers. If you are not cowards, kill me.”

But the court did not sentence her to death. She was exiled to New Caledonia, a barren island south of Australia, where she spent the next eight years of her life. The story of her revolutionary activity until she died in 1905 is another chapter to be told at another time.

This chapter of her life is a glorious example of the heroism of women fighters to be especially remembered on International Women’s Day and March 18th, the day of the Paris Commune. Many other heroic figures have taken their place beside Louise Michel through the years. Only a few weeks ago hundreds of Austrian working women took their places besides the men on the barricades against fascism and in defense of their homes. They have carried on as we must, the great tradition of working women fighters against misery and oppression. They have joined the ranks, as we must, of the army that is ready to die fighting for the right to live in a world free from hunger, war and terror, a world ruled by workers in their own interests and building their own future.

The Working Woman, ‘A Paper for Working Women, Farm Women, and Working-Class Housewives,’ was first published monthly by the Communist Party USA Central Committee Women’s Department from 1929 to 1935, continuing until 1937. It was the first official English-language paper of a Socialist or Communist Party specifically for women (there had been many independent such papers). At first a newspaper and very much an exponent of ‘Third Period’ politics, it played particular attention to Black women, long invisible in the left press. In addition, the magazine covered home-life, women’s health and women’s history, trade union and unemployment struggles, Party activities, as well poems and short stories. The newspaper became a magazine in 1933, and in late 1935 it was folded into The Woman Today which sought to compete with bourgeois women’s magazines in the Popular Front era. The Woman today published until 1937. During its run editors included Isobel Walker Soule, Elinor Curtis, and Margaret Cowl among others.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/wt/v5n02-feb-1934-Working-Women-R7524-R2.pdf