Maude Malone explains why she quit the Progressive Woman’s Union. A militant suffragette, trade unionist, and librarian who, in the 1930s, become the archivist and librarian for The Daily Worker. Ten years after this was written, Maude and her sister Marcella organized the first labor union for public librarians was The Library Employees’ Union of Greater New York was chartered as A.F. of L. local 15590 on May 15, 1917.

‘Bourgeois Suffragists Don’t Want the ‘Rabble’’ by Maude Malone from the New York Socialist. Vol. 18 No. 2. April 11, 1908.

Maud Malone Leaves the “Progressive” Woman’s Suffrage Union, and Gives Her Reasons–It Has Become Reactionary and Exclusive.

The following letter from Miss Maud Malone, well known for her activity in the movement for woman suffrage, will be of interest to our readers. It tells the story of the nature of one more attempt to make oil and water mix.

To the Editor: Will you kindly allow me space in your columns to announce my resignation from the Progressive Woman’s Suffrage Union and to explain my reasons for such action. In view of the fact that I have been connected with the movement in this city from the beginning, having organized and managed the open-air meetings in Madison Square and the Sunday parade and having organized the Union at my home, I would like to make my withdrawal as public as my connection with the Union has been. It is also due to the men and women who came into the movement believing that it was to be a democratic one, to tell them that certain influences have developed within the Union and obtained control over it which have changed its original policy to one of reaction and exclusion.

The present policy of the Union is: 1. “To attract a well-dressed crowd, not the rabble”; 2. To exclude from its platform woman suffrage speakers. against whom one or two men or women in the Union have a personal prejudice or who stand in the way of their ambition. It also seeks to exclude from its platform men and women who announce publicly that they are Socialists as well as suffragists. Unless they promise to make no reference whatever to the economic question they will be entered upon the Union’s blacklist and never asked to speak again. I am not a Socialist myself, but I have neither sympathy nor agreement with any organization which adopts this attitude of excluding women suffragists because of a difference of economic belief or because of a fancied social superiority.

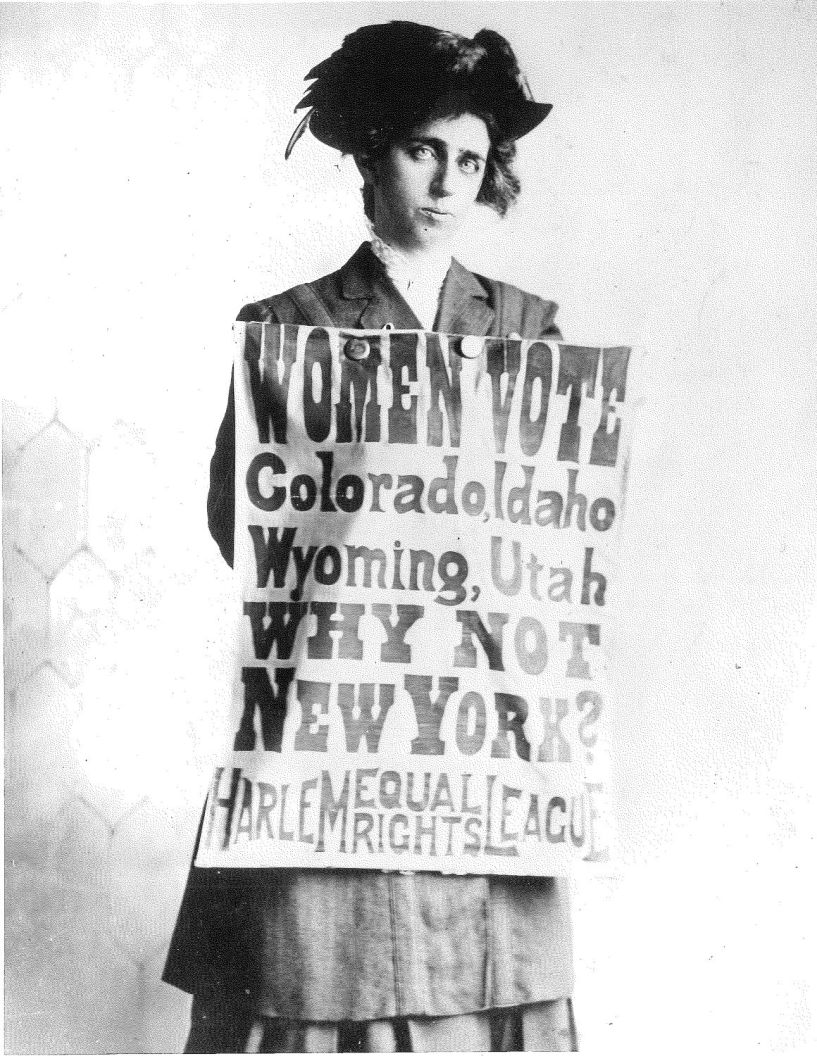

When, in April, 1907, the Harlem Equal Rights League voted to start open-air suffrage meetings, it was with the idea that it was a great opportunity to present our cause to men and women who would not come to hear the question debated in public halls or private drawing rooms. Business engagements prevented us from starting the open-air meetings during the summer as planned. In December. however, the Harlem Equal Rights League held its first open-air meeting in Madison Square and continued to held meetings there until the Union was organized.

It was in the broadest spirit of democracy that we went out into the streets inviting all passers-by to listen to our arguments, offer their objections or ask questions. To my surprise and disgust, however, the matter of clothes was the paramount issue in the mind or one of the members of the Progressive Woman’s Suffrage Union; speakers and audience were alike condemned as not being up to the required standard, and it was emphatically declared that we must attract a well-dressed crowd. In England, it was stated, the militant movement would never have succeeded without the aid of certain people to give it standing, and objection was made because of the bad impression it would make to have such clothes connected with the Union, and the absolute necessity was pointed out to me of attracting women of the upper classes, “who would not join as long as we had our present crowd”.

As to the question of the exclusion of certain speakers from our platform: Mrs. Cobden-Sanderson wrote to Mrs. Wells and volunteered to speak at our street meetings before sailing for England: Mrs. Wells objected because it would make the movement in New York too English if Mrs. Sanderson spoke; I laughed at this and insisted on Inviting Mrs. Sanderson to address our next meeting. Objection was made. to Mrs. Harriet Stanton Blatch speaking or joining the Union because her doing so would prevent another woman from coming in; I invited Mrs. Blatch to speak, nevertheless, which she did. Objection was made to another well known suffragist woman; as the reason was equally personal I paid no attention to it. Further objection was made to our Socialist speakers for having mentioned on the platform that they were Socialists as well as suffragists. In all of these cases I refused to exclude anyone from our platform who was a suffragist.

The movement, to be truly progressive, should recognize no prejudice of race, color, difference in clothes or in creed, whether religious or economic. This continuous contention by reason of petty spite and prejudice was to me not only undemocratic but nauseating. The progressive women of the Union are the women who have neither the time nor the inclination to work in an organization when it has degenerated into a movement to advance personal ambition, and when it has been placed on a false basis by having the interest behind that ambition finance the movement.

Because the original plan, which was to invite the cooperation of all sorts and conditions of men and women in the fight for woman’s rights, had been radically departed from I resigned from the Progressive Woman Suffrage Union on Feb. 21, at the committee meeting which adopted this policy of exclusion. Sincerely.

MAUD MALONE.

231 W. Sixty-ninth street.

The New York Call was the first English-language Socialist daily paper in New York City and the second in the US after the Chicago Daily Socialist. The paper was the center of the Socialist Party and under the influence of Morris Hillquit, Charles Ervin, Julius Gerber, and William Butscher. The paper was opposed to World War One, and, unsurprising given the era’s fluidity, ambivalent on the Russian Revolution even after the expulsion of the SP’s Left Wing. The paper is an invaluable resource for information on the city’s workers movement and history and one of the most important papers in the history of US socialism. The paper ran from 1908 until 1923.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-the-worker/080411-newyorksocialist-v18n02.pdf