A valuable explanation of the organs of power in the Soviet state as established by the 1918 Constitution and developed in the first years of the Revolution. In six parts: I. The All-Russian Central Executive Committee, II. The Council of People’s Commissars, III. The Council of Labor and Defence, IV. The All-Russian Congress of Soviets, V. Local Soviet Congresses, VI. Town Soviets.

‘How the Soviet Government Works IV: The All-Russian Congress of Soviets’ from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 6. No. 4. April, 1922.

THE supreme authority of the Soviet Republic in all matters is the All-Russian Congress of Soviets. As the Soviet in each town or village— the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council or the Peasants’ Council — concentrates in its hands all authority in the area for which it is elected, being composed of delegates from the workers elected at their place of employment, so the All-Russian Congress, composed of delegates from all the local soviets to whom the latter have for the time being handed over their plenipotentiary powers, has full powers conferred upon it in this indirect way by the Russian working class, which alone enjoys the full rights of citizenship in the Soviet Republic. During the four years of civil war and painful internal disorganization in which the first eight All-Russian Congresses assembled, there was little leisure or thought for reducing this principle of election of the congress to the most finished system. Quite apart, however, from the psychology of the revolutionary moment, which was not at all concerned with a completely accurate electoral system, a whole series of “checks and balances” existed to reassure the doubtful.

The Constitution of July, 1918, laid down (Part III, Chapter 6, Article 25) “The All-Russian Congress of Soviets is composed of representatives of town soviets on the basis of one deputy for every 25,000 electors and representatives of provincial congresses of soviets on the basis of one deputy for every 125,000 inhabitants.” This provision has at various times given rise to a great deal of misunderstanding; but the explanation is perfectly simple, and was very clearly presented at the Fifth Congress, when the draft Constitution was being discussed, by George Steklov, reporting on behalf of the Drafting Commission. As he pointed out at the time, the town soviets, which are themselves elected by compact groups of electors, with whom no other class of the population is intermingled (i.e. the workshops, factories, trade unions, etc.) naturally choose their representatives on the basis of number of electors and not number of population. In the case of the rural soviets and provincial congresses, on the other hand, where the chief occupation is that of agriculture, it is much more difficult to distinguish a hard and fast category of electors and still more so to assemble them in one place; and the first congresses of peasants’ soviets, which met as a separate organization in 1917, while the Provisional Government was still in power, quite naturally based their representation on the principle of one deputy for every 125,000 inhabitants. This relation took for granted that roughly one in every five of the inhabitants of the countryside was an elector (i.e., the head of household or an adult engaged all his time in production).

When the two All-Russian organizations of soviets — worker and peasant — amalgamated to form a single congress in November, 1917, they quite naturally maintained the dual system of election which practice had shown to be best adapted to the varied needs of Russia.

Again it had been made a subject of criticism that elections to the All-Russian Congress are indirect, i.e., that at best in the towns the constituents are two degrees distant from the body they have elected; while in the country, as the rural delegates to the provincial congresses are themselves elected by rural district congresses, the distance between the congress and the elector is doubled. Apart again from the fact that this is a feature of ordinary working-class organizations which any member of a trade union will recognize and understand, what the critics always overlooked was that the system of recall, constantly practised in the lowest units of the Soviet system, keeps them constantly in touch with the opinion of the overwhelming majority of the electors. Consequently, the special congresses which were always summoned during the last four years to elect delegations to the All-Russian Congress turned out to be almost automatic in their expression of the desires of the local public.

In addition, statistics of the Ninth Congress show that 885 of the delegates came from European Russia, 494 from the federated or allied Soviet Republics, 107 from Siberia, 54 from autonomous areas, and seventy-six from the Red Army.

To a certain extent the historical circumstances under which each of the congresses met determined its composition and work. The first, which met when the soviets were still a class organization pure and simple, with no legal standing or authority, busied itself with such questions as the financial resources of the Central Executive Committee, the attitude to be adopted toward the Provisional Government of Kerensky, the anti-war agitation of the Bolshevik Party (which then as we have seen above was still in a minority in the Soviets), the land reforms to be urged on the Provisional Government, etc. The Second Congress, which met on the day following the seizure of power in Petrograd by the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, in which the majority had for two months been Bolshevik, showed that the calculations of the Bolshevik Central Committee were not unfounded by giving a slight majority to that party. The work of this congress, therefore, consisted in laying the foundations of the Soviet State; the appointment of the Council of People’s Commissaries, the decree on the land, the decree on peace, the decree ordering the formation of revolutionary committees in the army, etc.

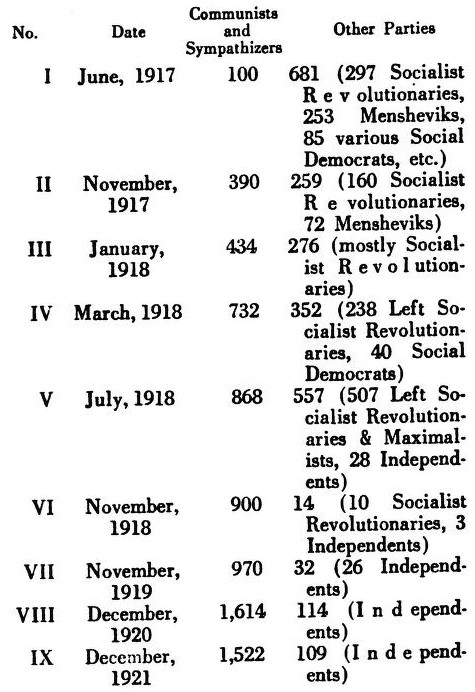

So far nine All-Russian congresses have taken place, one of them before the establishment of the Soviet Government. The following are the more important statistics of their composition:

From 1918 a curious coincidence decreed that the end of the year (and the anniversary of the November Revolution) should repeatedly fall in with a temporary relaxation of the pressure on the Soviet Republic. In Nov., 1918, the Czecho-Slovak rising had been crushed and the first White detachments from Siberia were driven back to the Urals, while Kolchak had only just seized power at Omsk and did not as yet constitute a real menace. In November, 1919, Kolchak, Denikin, and Yudenich had been crushed in the east, south, and north-west, and General Wrangel was engaged in rallying the last remnants of the White “Volunteer” army for a desperate stand in the Crimea. In December, 1920, the menace of Wrangel and the unexpected Polish attack of the spring had both successfully been liquidated; and the All-Russian Congress introduced into its labors that dominant economic note which in normal circumstances should be the characteristic of such an Assembly in a Socialist Republic, and which became still more accentuated at the Ninth Congress a year later. In December, 1921, there was practically no fighting to look back upon; but the stress and strain involved in the transition to the new economic policy had been almost as effective in preventing the earlier summons of a Congress. Once again December brought with it all the suitable circumstances for a review of the general national situation; the new economic policy could now produce its first quarterly reports, albeit incomplete and sketchy. On this occasion the Congress prudently enacted that for the immediate future at any rate All-Russian congresses were to meet yearly instead of every six months.

The Ninth Congress which met in the last week of December, 1921, finally established as a rule of law what practical experience had already made an almost universal custom—that elections of town soviets and rural district, county, and provincial congresses should take place in future once a year, and during the month immediately preceding the assembling of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets. In this way a definite step is taken to insure, in law a well as in fact, that the All-Russian Congress shall reflect as nearly as possible—more nearly than has been possible during the first years of the Soviet Republic—the interests and points of view of the locality.

With the completion of a year’s more or less peaceful reconstructive work, and the prospect of some opportunity for the future of continuing that work undisturbed by external foes, there is every likelihood that the All-Russian Congress of Soviets will continue to function as the effective supreme controller of the destinies of the Russian working community of Soviet Republics.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v6-7-soviet-russia%20Jan-Dec%201922.pdf