Beginning in his lifetime, and for a variety of reasons, Karl Liebknecht was seen as the voice of patron revolutionary youth. That status became codified in the Communist movement as Liebknecht Day, an anti-militarist commemoration January 19, the day in 1919 when he and Rosa Luxemburg were murdered.

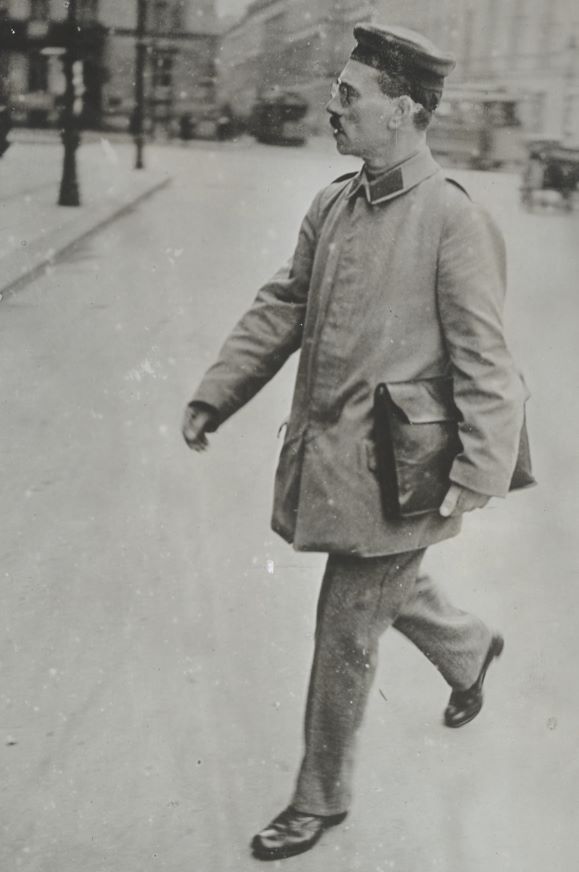

‘Karl Liebknecht–Leader of the Youth’ by Herbert Zam from Workers Monthly. Vol. 5 No. 3. January, 1926.

“In the Russian embassy in Berlin,” writes Nikolai Bukharin, “we celebrated the release of Karl Liebknecht from prison. Many people were there—the society was rather mixed…All spoke but no one made such a deep impression upon me as a young worker a young man with one arm and a thin face with yellow cheeks. He spoke with such a firm belief in our victory that every revolutionist present felt that such a generation must be victorious. Karl himself felt this also…Most of what Liebknecht said was addressed to him, for there existed a close connection that bound them together. LIEBKNECHT WAS ALWAYS SURROUNDED BY THE YOUTH; it was these ‘children’ who above all took part in the street battles and demonstrations.

“Some days later the young comrade was injured in a street fight—a police sword had hit his arm stump.

“Mehring no longer lives and Liebknecht is dead; even Haase has been buried by the hangmen of Scheidemann. I do not know whether the young comrade with the one arm still lives. But this | know—the German working class youth still lives, the revolutionary spirit with which Liebknecht was baptised still lives.”

Liebknecht—Leader of The Youth.

“Liebknecht was always surrounded by the youth!” It was this intimate relation with the revolutionary youth that was the keynote of the whole career of Karl Liebknecht; it was this bond that determined his relations to the proletarian movement and to the social democratic party. It was this consuming interest dominating his whole life that made Karl Liebknecht at the age of 49 (he was of the same age as Lenin.) still one of the “young” and a leader of the youth.

The Significance of the Attitude Towards the Proletarian Youth.

Zinoviev has well pointed out that one’s attitude to and conception of the youth movement can serve as an excellent criterion for one’s relation to the proletarian movement as a whole and position in regard to its various tendencies. It is only the true revolutionary, the Bolshevik in the real sense of the word, the proletarian leader who seriously addresses himself to the problem of the proletarian revolution, who can deeply appreciate the full significance of the movement of the working youth and who can assume a proper attitude towards it.

Towards the beginning of the century the deep-going opportunism that was to turn the whole social democracy into a “whited sepulchre” was already becoming more and more evident. The trade union and socialist leaders were losing contact with the masses, were getting out of touch with their daily struggles, were responding to the triumphant march of imperialism with more and more reformist and compromising tactics, and were slowly becoming transform ed into conscious or unconscious agents of the capitalists. To the official labor movement of Germany the proletarian revolution was losing its clearness; it was becoming more and more a matter for abstract propaganda and was regarded very uneasily from the point of view of practical possibility.

The Reformists and the Youth.

To such people the youth movement did not present itself in a very welcome form. The youthful proletariat has no “aristocracy” in whom opportunism and reformism can find a basis; the youthful proletariat is largely unorganized, suffers from long hours, most miserable conditions, and intolerable treatment; the youthful proletariat is subjected to forced military service and bears the brunt of militarism. Psychologically also the young workers are the bearers of a living revolutionary spirit, a spirit of unrest and dissatisfaction, a spirit of revolution. In the ranks of the workers, therefore, the youth form the most proletarian, the most revolutionary section of the toiling masses.

To the comfortable, well-fed, and self-satisfied bureaucrats the movement of the revolutionary youth was a constant and serious menace. It was as a breath of fresh air rudely disturbing the stale atmosphere of officialdom, It brought the spectre of the proletarian revolution vividly before the frightened eyes of the well-established trade union and party leaders. These gentlemen, therefore, quite systematically paid no attention to the plight of the young workers and regarded every move in the direction of approaching the youth as “dangerous” to a degree. The very thought of organizing the young workers on a real militant basis was anathema to them and the most they could see in the youth was a loose non-political, social, and cultural organization. “The youth must not interfere in politics” solemnly maintained the reformists who were mortally afraid that the proletarian spirit and the revolutionary impetuosity of the working youth would cause them no end of “trouble.” Nowhere was the opportunism of the social democratic and trade union bureaucrats more marked than in their attitude towards the nature and functions of the socialist youth movement.

Liebknecht Fights for the Youth.

It was Karl Liebknecht who from the very first took upon himself the not very grateful task of championing the cause of the young workers within party circles and without. In committees and conferences of the social democratic party and of the trade unions, everywhere he could possibly get a hearing, Liebknecht was perpetually putting forward the case of the toiling youth and demanding aid for their organization. It may well be imagined what uphill work it was to convince the bureaucrats of the necessity for a youth movement. Finally, however, the beginnings were made with the formal and grudging consent of the Party officialdom but, as Liebknecht himself complained, against their active and systematic sabotage. At any rate, the beginning was made and the Young Socialist League was formed. To this league and to its counterparts in the other countries of Europe Liebknecht dedicated his best efforts and his most brilliant work.

Liebknecht and the Anti-Militarist Struggle.

It was to a section of the Young Socialist League that Karl Liebknecht, in 1906, delivered his course of lectures on Militarism and Anti-Militarism. The problem of militarism is predominantly a problem of the working youth, for the young workers and peasants form the vast bulk of the conscript armies of the bourgeoisie and bear the full brunt of capitalist militarism. It is a sign of the real proletarian spirit of Liebknecht that he, above all others, immediately saw the truly revolutionary implications of the struggle against militarism and called upon the whole working class to give its full aid to the proletarian and peasant youth in their campaign against it. Liebknecht was the prophet not only of the revolutionary youth but also of the revolutionary struggle against capitalist militarism that now constitutes one of the primary forms of activity of the Young Communist International.

“Militarism,” wrote Liebknecht, “is not only a means of defense against the external enemy; it has a second task, which comes more and more to the fore as class contradictions become more marked and the class consciousness of the proletariat continues to grow. Thus the task of militarism is to uphold the prevailing order of society, to prop up capitalism and all reaction against the struggle of the working class for freedom. Militarism manifests itself here as a mere tool in the class struggle, as a tool in the hands of the ruling class. It has the effect of retarding the class consciousness of the proletariat in co-operation with the police and the courts, the school, and the church.”

“Anti-militarist propaganda must cover the entire country like a net,” wrote Liebknecht addressing his words to the whole proletariat but particularly to the revolutionary young workers. “The proletarian youth must be systematically imbued with class consciousness and with a hatred for militarism. Agitation of this kind would strike a response in the warm hearts and the youthful enthusiasm of the young proletarians. The proletarian youth belongs to the social democracy. It must and will be won over if everyone does his duty. He who has the youth has the army!”

These lectures, immediately published in book form, caused a sensation thruout Germany and shocked the bourgeois authorities hardly more than it did the respectable social democratic leaders. It may well be imagined how the Prussian military state reacted to this fundamentally revolutionary attack of Liebknecht. “Guilty of a treasonable undertaking. condemned to eighteen months’ imprisonment in a fortress…all copies of the book and all plates and forms are to be destroyed…” This was the verdict after a sensational trial with which it is said the kaiser himself was kept in touch thru a private wire.

Liebknecht in Parliament.

Lenin has more than once held up the work of Liebknecht as a model of revolutionary parliamentarism, as an example of the revolutionary use of parliament as an arena of struggle. In truth, Liebknecht deserved this praise. But it was not only during the war that the revolutionary courage and foresight of the great leader were evident. From the time he was elected to the Prussian Diet, Karl carried the class struggle of the proletariat and of the proletarian youth into that body and used it as a tribune from which to address the millions of workers and peasants of Prussia. Again the problems of the youth were foremost in his mind. Militarism and the struggle against it stood in the front rank. But the question of education also preoccupied him and it was on this issue that he succeeded so well in exposing the hypocritical class nature of the whole cultural apparatus of bourgeois society.

“We cannot separate,” Karl spoke to the young workers and peasants of Germany from his place in the Diet, “the educational from the social systems…Education under capitalism is not an aim in itself…The higher schools serve as institutions for preparing higher state officials while the elementary schools are used today to consolidate the position of the ruling classes, to capture the souls of the young proletariat for the ruling classes, for militarism…You are trying to give the impression that you are throwing open the road of education to the people but that is only because you require educated soldiers.”

It is clear that Karl Liebknecht himself consciously dedicated his whole life to the cause of the enlightenment, organization, and mobilization of the toiling youth against capitalism. It is for this reason that the revolutionary young workers of the world over now hails the martyred hero as the leader of the revolutionary youth.

The War Breaks Out—The Collapse of Social Democracy.

But it took the war to provide a fitting background to bring out the true greatness of the man. We all know what happened before and as the war broke out. The grand moguls of social democracy had solemnly met year in and year out before 1914 and passed one resolution after the other declaring that under no circumstances would the proletariat permit the occurrence of the great world war everyone knew was coming. It was only a few profound Marxists like Lenin who could see that these brave words covered a rotting corpse and that the whole imposing structure of social democracy was but housing a stinking carcass. It took the outbreak of the war to convince the honest workers of this. The rottenest reformism, the most shameless social patriotism immediately took control of the workers’ organizations and began with the greatest enthusiasm the task of turning over the working class body and soul to the general staff. Those who had been loudest in proclaiming their international solidarity, now without any hesitation flocked to the support of their respective bourgeoisies. The whole social democratic Party and the social democratic trade unions became transformed into departments of the German war machine. And not only in Germany, in Belgium, in France, in England, everywhere, “class peace” (Burgfrieden) was declared. Each to the defense of his own fatherland—as Kautsky sagely proclaimed.

Liebknecht Fights the Imperialist War.

In all this madhouse one clear voice could be heard— the voice of Karl Liebknecht. This man who had been dubbed “eccentric” and “stormy petrel” because of his militant championing of the role of the youth and of the struggle against militarism, now became more “eccentric” and more “stormy” than ever. He spoke against the war—he voted against the war—he fought it. That at first he was alone did not daunt him. Soon he succeeded in gathering around himself a few other comrades who had remained faithful to the cause of the struggle against the bourgeoisie and for the emancipation of labor—Luxemburg, Mehring, Jogisches, Zetkin, and together with them organized an extreme left wing within the social democratic party devoted to the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat, against the war and for freedom.

“Forward Against Capitalism, Against the Government!”

Of course, the German general staff was quick to retaliate. To imprison Liebknecht or to murder him openly was out of the question—for so beloved was Karl by the workers that the German state simply did not dare to make any open move against him. So, early in the war, he was conscripted into the army. But here too, he continued his propaganda. On May 1, 1916, while he was in Berlin on leave he became the center of a tremendous May Day Anti-War demonstration in the great public square before the kaiser’s palace. In full uniform the heroic Karl flung these stirring words to the huge masses mad with enthusiasm:

“Let thousands of voices shout: ‘Down with the shameless extermination of nations! Down with those responsible for these crimes! Our enemies are not the English, French, or Russian workers but the great German landed proprietors, the German capitalists, and their executive committee, the government.

“Forward. Let us fight the government. Let us fight these mortal enemies of all freedom. Let us fight for everything which means the triumph of the working classes, the future of humanity and civilization!”

The German Masses in Motion.

Of course, Karl was immediately arrested. But the German masses were already moving. Strike after strike broke out–continually growing and expanding to ever wider proportions. It was this movement of revolt that two years later unseated the kaiser and the landowners and placed the power for a brief period of time into the hands of the false representatives of the proletariat.

The Social Democrats Incite Against Liebknecht.

The hatred and fear of the German state for Karl Liebknecht was heartily shared by the shameless betrayers of the Germen workers–the socialist and trade union officials who now became the most open agents of the military ma chine. The whole party apparatus was mobilized against and his comrades. The worst passions of the lowest strata of the German workers were incited against them. They were publicly baited as “mad dogs” and “scum of the earth.” The social patriotic jingoes who were licking the boots of von Hindenberg were frothing at the mouth in their wild hatred of the heroic Liebknecht. These were the same men—these bureaucrats and “leaders”—who had 4 few years before shaken their heads and spoken pityingly of the “madcap” Karl who actually wanted to organize the “reckless” and “impetuous” youth for the struggle against capitalism. History indeed has a knack of placing fitting conclusions to its tales.

October, 1917.

In 1917, the world proletariat broke through the chain of capitalism at its weakest point—on the Russian sector— and in the fall of that year the Russian proletariat and poor peasantry took power. The world proletarian revolution was begun! October, 1917, resounded through the world!

The German Revolution and the Treason of the Social Democrats.

In Germany the collapse came towards the end of 1915. The kaiser fled the land. The workers everywhere threw off their yoke. Liebknecht was released and again became the idol of the masses. He immediately saw that the social democrats were actively engaged in robbing the workers of the fruits of their struggles, in liquidating the revolution and in turning the state power over to the bourgeoisie who were too weak to seize it themselves. With all the fervor of their profoundly revolutionary spirit Liebknecht and his comrades threw themselves into the work of showing the German working class the road to emancipation that had already been trodden by the Russian proletariat under the guidance of the Bolsheviki and of organizing them for the struggle. It was at this point that the full baseness and murderous lust of the “humanitarian” and “civilized” social democrats became evident. It was now that they showed themselves to be as bitter enemies of the cause of the proletariat as ever their masters, the capitalists themselves.

Liebknecht is Murdered!

It would require too much space here to recount the already well-known tale of Spartacus—of the organization of the Spartakusbund and of the uprisings and struggles it led. In these Liebknecht’s “children,” the working youth, played the leading part for was the youth ever absent when there was revolutionary work to be done and revolutionary struggles to be fought! We know too well of the bloody provocations of the Scheidemann-Ebert Vorwaerts against the leaders of the struggling proletariat, of the blood-hound Noske, of the blood bath into which these “peaceful” gentlemen plunged Berlin and Germany. They did their duty—to the capitalist masters. But the working class will remember these people who served the capitalists in the ranks of the working class! Liebknecht Lives in the Revolutionary Youth.

Liebknecht and Luxemburg are dead—murdered by the social democrats for their service to the revolution. But the banner they bore has not fallen. The Red Flag of the proletarian revolution is still aloft—waving defiantly in the face of the imperialists. And rallying around the banner of the embattled toilers, in the front line of the struggle for the emancipation of labor and of humanity, are the spirited ranks of the proletarian youth—the youth for whom Liebknecht fought, whom Liebknecht inspired, whom Liebknecht taught, whom Liebknecht organized, whom Liebknecht led, for whom Liebknecht died!

The spirit of Liebknecht lives in the youth—in the Young Communist International.

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1926/v5n03-jan-1926-1B-WM.pdf