Pioneering Black historian Asa H. Gordon positions the struggle for ‘physical freedom’ by the enslaved as a constant that became the engine for both the abolition and secessionist movements leading to the Civil War in an address delivered at the annual meeting of the Carter G. Woodson’s venerable Association for the Study of African American Life and History in Pittsburgh on October 24, 1927.

‘The Struggle of the Negro Slaves for Physical Freedom’ by A.H. Gordon from Journal of Negro History. Vol. 13 No. 1. January, 1928.

We propose to set forth in a few words the Negro’s fight for physical freedom. American history is strangely silent on this subject. There are whole libraries of books on the Civil War, its causes and effects. One of the causes of this war, the Negro’s fight for freedom, is scarcely mentioned in most histories. This neglect of the Negro’s own effort to achieve his freedom has resulted in a widespread, in fact, an almost universal belief, that the Negro slaves did nothing at all to break their shackles. Many people believe that their freedom was a more or less undeserved and perhaps unwelcome blessing which was thrust upon the Negroes by the events of history. This theory, plausible because of the neglect of this aspect of our history, is excellent “support” for the theory of Negro inferiority. In fact, if it were really true that the Negro made no effort for his liberation, this fact would be positive proof that the Negro is in truth inferior as a human being. It is unfortunate for those who would like to prove the theory, however, that there are numerous facts to show that in various ways the Negroes did keep up the fight for their freedom. Facts to which we expect to call attention in this address seem to suggest that if the slaves had not fought for their freedom there probably would never have been a Civil War and consequently no freedom for the Negro, at least at the time he received it.

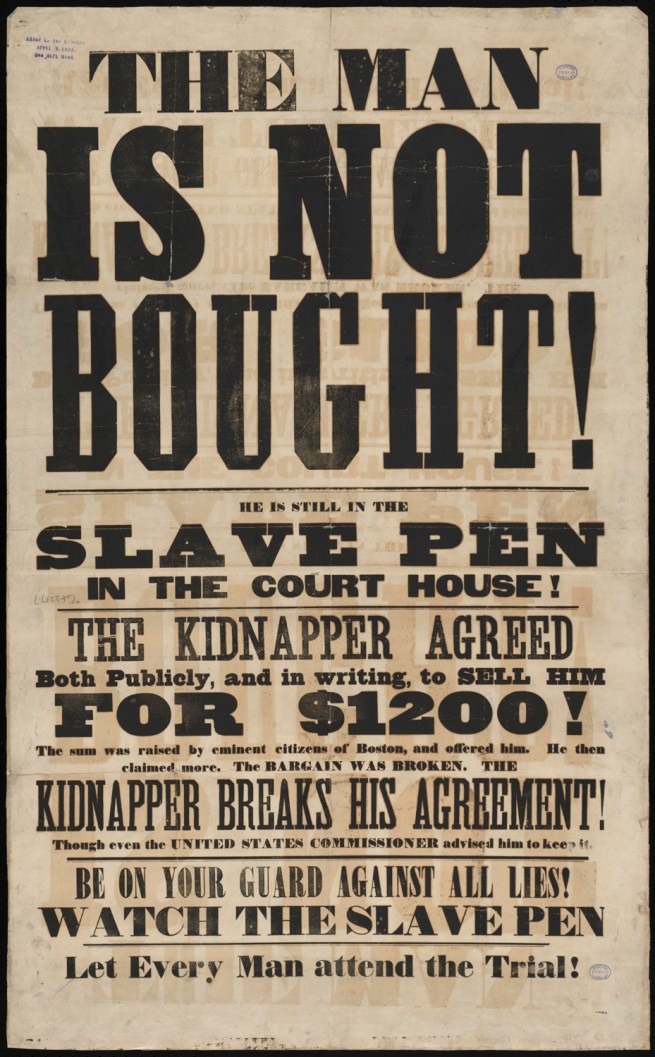

We shall try to mention here the ways in which the slave fought. It will be our task to show how the Negro’s fighting spirit, though often shown in strange and peculiar ways, was the inspiration and always the ally of those influences and events which historians admit to be the things which made freedom for the Negro ultimately inevitable. William Pickens once made a remark to the effect that “the first abolitionist was the runaway slave.” His remark is full of philosophy. The runaway slave was obviously the cause of the Fugitive Slave Law. The Fugitive Slave Law was the never-failing stimulus for the abolitionists. The flight of the fugitive made slave property uncertain.

Almost at an instant that slavery was introduced slaves began to run away. The fugitive slave was a courageous fighter. This is readily realized when we admit there are many more ways of fighting than physical conflict. The fugitive slave reasoned that this method of abolishing his personal slavery was the safest and surest method usually open to him. It was far from easy and safe. The early slaves found difficulty in deciding whither they might run away and hide. The Indians were near by, but the black slave could not be sure of a sympathetic reception from these wild men. However, many of the first fugitive slaves went to the Indians and threw themselves upon their generosity and kindness. In many instances these fugitives were warmly received and humanely treated. Many of them intermarried with the Indians and some of their mixed breed descendants, like Osceola, were among the greatest leaders of the Indians.

The love of freedom was so strong in some of the slaves that they ran away even though they had no definite place to go. They went off to die in the forests and mountains if they could not live on the grain, wild fruits, and birds which they could find in these hiding places. As soon as the slaves somehow got some vague ideas of the geography of the country and some idea of the direction in which they could discover friends who would help them to escape, they began to run away toward the North into the States above the Mason and Dixon Line and even into Canada. The slave who undertook to escape from slavery in the lower South by fleeing to the North was evidently undertaking a long, tedious, and dangerous journey. With the methods of travel available in those times and with the handicaps of a fugitive from the clutches of the law, upheld by almost solid public opinion throughout the South, the distance to freedom must have indeed seemed great to the lonely black slave meditating and planning his escape from a Southern plantation. It is true that the escaping slave could always depend upon co-operation from the majority of his fellows laves, but he could not be sure of all of them. Some of the slaves, feeling that they were running too great risks in attempting to help their fellow sufferers to escape, refused to give them aid. The fugitive, therefore, had to be very careful because one mistake in reference to who was a friend or enemy among his fellow slaves might cause him to be captured and returned to a revengeful master before he had actually started on the rocky road to freedom.

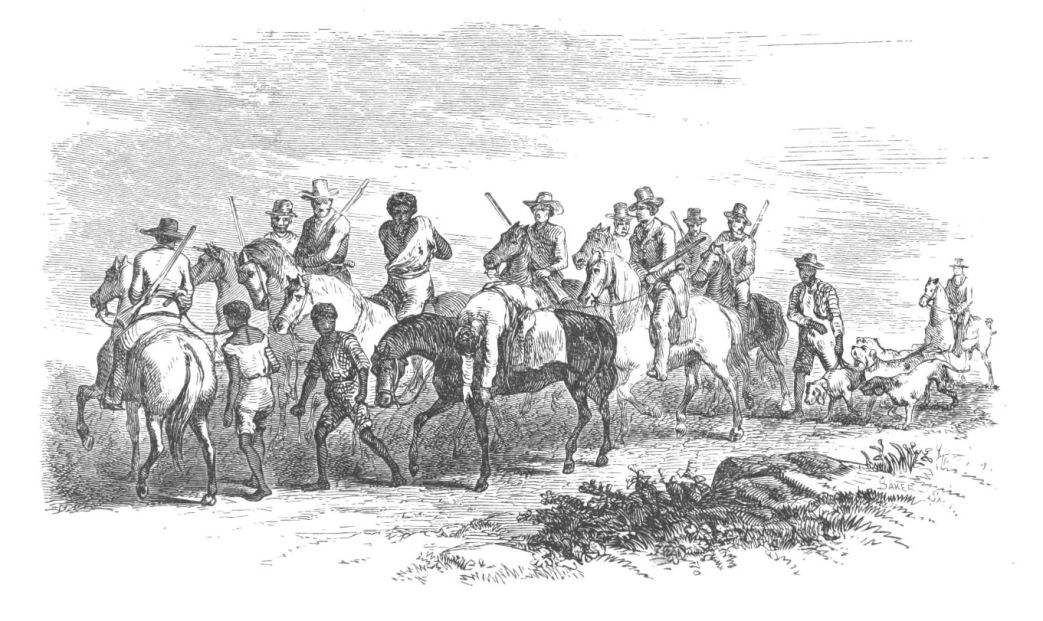

The slave owners developed an effective system of apprehending fugitives because they realized that this habit of running away was one of the most subtle and dangerous methods of fighting slavery that the well nigh helpless slaves could command. As soon as it was detected that a slave had escaped a descriptive advertisement of him was published far and wide as quickly and efficiently as the methods of communication available at that time would permit. Rewards of no mean value were offered for the capture of these fugitives, sometimes dead or alive; and a vigorous search and pursuit immediately followed. Dreadful bloodhounds trained especially for the purpose, and men little less bloodthirsty than the hounds, were put upon the trail. The fugitive was hotly and relentlessly pursued. The slave catchers felt no scruples against killing the slave as they would a fleeing rabbit or deer if he could not be captured alive or if he put up a dangerous resistance when cornered. Many escaping slaves lost their lives in fierce conflicts with bloodhounds or in desperate efforts to overcome the handicaps offered by cold, rain, rivers, mountain-passes and many other obstacles never known or recorded. This was a much more hazardous journey than Lindbergh’s recent flight to Paris.

The successful runaway slave was not only an abolitionist in the narrow sense in that he abolished his own personal slavery, but in a larger and more important sense he helped the abolition movement by provoking the slave-owning class to attempts at retaliation which were so cruel and inhuman that they advertised the whole system of slavery as infamous. The romance of their never ceasing fight furnished inspiration and concrete material for multitudes of anti-slavery propagandists with less influence and skill than Harriet Beecher Stowe, but agitating nevertheless with some effect. The fact that the slaves were willing to take the risks involved in such an undertaking in the face of the terrible odds was forceful proof to the abolitionists that these bondsmen should be free. Other convincing evidence for the abolitionists was the skill shown by many of the slaves in their methods of eluding the white officers of the South and in effecting their freedom in spite of the carefully laid plans by the “superior” whites. The Underground Railroad saw many flashes of genius along its busy lines.

One very important fact which should not be overlooked in discussing this fight for freedom by the fugitive slaves is that many of the bravest and best officers of the Underground Railroad were Negroes. Among them was William Still who was chairman and secretary of one of the most active branches. In the preface to his book, The Underground Railroad, Mr. Still describes his own work as follows:

“In these records will be found interesting narratives of the escapes of men, women and children from the present House of Bondage; from cities and plantations; from rice swamps and cotton fields; from kitchens and mechanic shops; from border states and gulf states; from cruel masters and mild masters; some guided by the North star alone, penniless, braving the perils of the land and sea, eluding the keen scent of the bloodhound as well as the more dangerous pursuit of the savage slave hunter; some from secluded dens and caves of the earth, where for months and years they had been hidden away awaiting the chance to escape; from mountains and swamps, where indescribable sufferings and other privations had patiently been endured. Occasionally fugitives came in boxes and chests, and not infrequently some were secreted in steamers and vessels, and in some instances journeyed hundreds of miles in skiffs. Men disguised in female attire and women dressed in the garb of men have under very trying circumstances triumphed in thus making their way to freedom. And here and there, when all other modes of escape seemed cut off, some, whose fair complexions have rendered them indistinguishable from their Anglo-Saxon brethren, feeling that they could endure the yoke no longer, with assumed airs of importance, such as they had been accustomed to see their masters show when traveling, have taken the usual modes of conveyance and have even braved the most scrutinizing inspection of slave holders, slave catchers, and car conductors, who were ever on the alert to catch those who were considered base and white enough to practice such deception.”

It is clear then that the fugitive slaves were not only consciously fighting for their own individual freedom but they were sometimes consciously and sometimes unconsciously fighting for the cause of the ultimate general emancipation of all the slaves. The large number of cases of slaves running away caused the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 which helped bring on the Civil War. The Negro officers of the Underground Railroad and other Negro assistants of fugitive slaves, of course, were working in the ranks of the abolitionists.

The Negro slaves also fought for their freedom in more direct and definite ways. Many fought for freedom through hard labor and rigid economy. Some fought for freedom by what Doctor DuBois calls the “appeal to reason.”

Very early in the history of slavery some of the slaves began to secure their freedom by purchasing themselves or their relatives. It was a courageous undertaking for a slave of such a little earning power to undertake to purchase both himself and his family. This difficulty grew out of several things. The slave had to work most of his time for his master and therefore had only “spare” or overtime at night, and on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays. Many of them worked for unusually low wages. The wages were scarcely over $20.00 per month as a maximum; slaves found it difficult to earn more. It took a very long time, then, for the worker to save enough to buy himself or a loved one.

Many fought it through to a successful conclusion, however, and thereafter enjoyed a few fleeting years of comparative freedom.

In exceptional cases unusually generous or far-sighted masters would allow their slaves to hire themselves. All they could earn above the amount which they paid the master they were at liberty to use in any way they chose. The greatest desire of most of the slaves being freedom, they usually saved to buy themselves.

This act of giving the slave the opportunity to buy himself was not always due to humanitarian or Christian sentiments. In some instances, it was due to the fact that the slave owners, realizing that slave labor was an economic failure, planned by offering the slaves the great blessing of personal freedom, to make him approximate the efficiency and economy of a free laborer. The scheme was not a bad one judged by results obtained in several instances. This point is well explained by Booker T. Washington as follows:

“When he (the master) allowed them (the slaves) to buy their own freedom, it was a practical recognition that the system was economically a mistake, since the slave who could purchase his freedom was one whom it did not pay to hold as a slave. This fact was clearly recognized by a planter in Mississippi who declared that he had found it paid to allow the slaves to buy their freedom. In order to encourage them to do this he devised a method by which they might purchase their freedom in instalments. After they had saved a certain amount of money by extra labor, he permitted them to buy one day’s freedom a week. With this much capital invested in themselves, they were then able to purchase, in a much shorter time a second, a third and a fourth day’s freedom, until they were entirely free. A somewhat similar method was sometimes adopted by certain freedmen for purchasing the freedom of their families. In such a case the father would purchase, for instance, a son or a daughter. The children would then join with their father in purchasing the other members of the family.”1

Illustrative of this method of purchase is the interesting story of George and Susan Kibby of Saint Louis told by Trexler as follows:

“In 1853 Kibby entered into a contract with Henry C. Hart and his wife Elizabeth L. Hart to purchase their Negress named Susan, whom he wished to marry. The price was eight hundred dollars. The contract is devoid of all sentiment and is as coolly commercial as though merchandise was the subject under consideration. Kibby had two hundred dollars to pay down. He was to pay the remainder in three yearly installments, and upon the fulfilment of the contract Susan was to receive her freedom. In the meantime Kibby was to take possession of Susan under the following conditions: ‘Provided however said Kibby shall furnish such security as may be required by the proper authorities, to such bond as may be required for completing such emancipation, so as to absolve…Hart and wife from all liability for the future support and maintenance of said Susan and her increase. This obligation to be null and void on the part of said Hart and wife, if said Kibby shall fail for the period of one month, after the same shall for the time become due and payable, to pay to said Hart and wife said sums of money as herein before specified, of the annual interest thereon, and in the event of such failure, all of the sum or sums of money whether principal or interest, which may have been paid by the said Kibby shall be forfeited, and said Kibby shall restore to said Hart and wife said Negro girl Susan and such child or children as she may then have, such payments being hereby set off against the hire of said Susan, who is this day delivered into the possession of said Kibby. And said Kibby hereby binds himself to pay said sums of money as hereinbefore specified, and is not to be absolved therefrom on the death of said Susan, or any other contingency or plea whatever. He also binds himself to keep at his own expense a satisfactory policy of insurance on the life of said Susan, for the portion of her price remaining unpaid, payable to T.J. Brent, trustee for Mrs. E.L. Hart, and that said Susan shall be kept and remain in this County, until the full and complete execution of this contract.”

“Attached to the back of this contract are the receipts for the installments. The first reads thus: ‘Received of George Kibby one mule of the value of sixty-five dollars on within contract Feb. 1st, 1854, H.C. Hart.’ The fifth and last payment was made on December 3, 1855—two years lacking six days following the date of the contract. Accompanying the contract is the deed of manumission of Susan, likewise dated December 3. Thus Kibby fulfilled his bargain in less than the time allowed him.”2

The Negro slaves made an effort for freedom through appeals to the sense of fair play and feeling of common humanity which the Southern white people always possessed. Of course, the nature of slavery was such that the bondmen had to be interested in the question of freedom. Diplomacy on the part of the slave dictated that he be not radical on the question, but there were some Negroes who did not hesitate to condemn the system and to denounce their own masters for wrongfully holding them in bondage. Many of these brave advocates of freedom became martyrs for their frank opposition to the prevailing regime, but their sacrifice was a worth-while contribution in the fight of the Negro slave for liberty.

The Negroes also presented a kind of mute appeal to reason by conduct worthy of freemen. Many a slave convinced his master that he ought to be free because he conducted himself with such manly and honorable bearing that the master’s reason suggested that it was folly to deprive such a man of his freedom. The Negro slave who displayed the essential qualities of manhood in so far as such a thing could be done under the limitations of the life of a slave was a tremendously effective argument in favor of emancipation. Such individuals among the slaves were proof that the theory of racial inferiority was a fiction. As this belief in the Negro’s hopeless inferiority was one of the fundamental pillars of the slave owner’s philosophy, when this theory was exploded the whole system seemed to weaken.

The character of the Negro was continually disturbing the tranquility of the minds of the slave owners. All this constituted a part of the Negro slaves’ marvelous fight for freedom. The slave rightly drafted the Christian religion to help him challenge the justice and righteousness of slavery. When a Negro slave professed and adopted the religion of Jesus he thereby became a “brother in Christ” of his master and oppressor. The Negro was not slow to impress the master with the fact that slavery was incompatible as a relationship between fellow Christians. The Negro, as a rule, even as he is today, was too diplomatically polite to be offensively rude; but how could the sensitive white master hear his fellow Christian, the slave, singing “Everybody talkin’ ’bout Heaven Aint goin’ dare” without feeling that he was being gently rebuked for holding the singer in bondage contrary to the teachings of Him who taught his disciples to pray, “Our Father”? The Negro slave also demolished the argument for racial inferiority with the matchless story of the Good Samaritan. This was indeed subtle but very effective fighting for freedom.

We may illustrate how this subtle method of fighting for freedom accomplished results by quoting a statement from the pen of Henry Laurens, a distinguished South Carolina statesman and leader. Writing to his son, this great man expressed himself thus:

“You know, my dear son, I abhor slavery. I was born in a country where slavery had been established by British Kings and parliaments, as well as by the laws of that country ages before my existence. I found the Christian religion and slavery growing under the same authority and cultivation. I nevertheless disliked it. In former days there was no combating the prejudices of men supported by interest; the day I hope is approaching when, from principles of gratitude as well as justice, every man will strive to be foremost in showing his readiness to comply with the golden rule.”

What caused Laurens, born and nursed in the cradle of the slave regime, to “abhor slavery”? Some may say that it was his innate love of freedom. There may be something in that, but I am constrained to believe that the character of the Negro slaves and their half mute appeal for freedom had much to do with converting this great man and many others to this way of thinking. The attitude of certain men like Laurens resulted in the freeing of many Negroes and some of these free Negroes used their liberty to fight more effectively for freedom for all.

It must be said that a few of the free Negroes failed to catch the vision of the righteousness of general abolition and too often entered into the support of the slave regime by purchasing and holding slaves themselves as far as their means and ability would permit them. It is said that 3777 Negroes owned slaves in 1830.3 But these Negro slave owners were hopelessly in the minority and were ineffective in their opposition to the Negro in his self-directed fight for freedom. Negro slaveholders were merely the exception that proved the general rule that the freedom of the Negro was achieved like that of all free peoples, because he fought for it, assisted by friends of the other races. It should be noted also that many of the Negroes who held slaves did so to keep them from being sold into other hands where they would receive less sympathy. This is the testimony of Miss Mae Holloway, of Charleston, whose family held slaves. Some of the slaves of Negroes thus reported, moreover, were their wives or husbands and children whom they could not manumit unless they left certain slave states.

Although the writer believes that the facts herein presented are significant in the fight of the Negro slave for freedom, there are doubtless those who think that most of this is a belabored or far-fetched argument. However there is yet to be recorded the story of more definite fighting—unmistakable physical fighting—which the Negro slaves engaged in to procure the coveted prize of freedom. The Negroes started fighting physically for their freedom as soon as they were captured on their native soil in Africa. Many of them died there fighting. Others died in conflicts on the sea. Still others began fighting as soon as they landed in America. A few fought single handed and a few joined the Indians and battled with them.

It is true that the majority of the Negro slaves who finally came to this country did not engage in physical conflict to procure their freedom because, as we have said previously, they did not consider that a safe or efficient method under the circumstances which prevailed. If they engaged in open rebellion the chances were ten to one that they would be destroyed. The slave regime was well organized and fortified against rebellion. Those who showed signs of chronic determination to appeal to physical resistance were cruelly punished and ruthlessly eliminated. A distinguished Negro writer has expressed this idea as follows: “A long, awful process of selection chose out the listless, ignorant, sly and humble and sent to heaven the proud, the vengeful and the daring. The old African warrior spirit died away of violence and a broken heart.”4 But “the old African warrior spirit died” hard and was instrumental in causing much bloodshed before its heart was broken. Writers agree that the Negroes who first came into North American territory as slaves were far more war-like and prone to rise and fight than those who came along later when the process of selection which DuBois referred to in the quotation above had been in operation long enough to produce its deadly work. Yet, the Negro slaves kept on fighting physically from time to time until slavery was destroyed by Abraham Lincoln’s famous Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment.

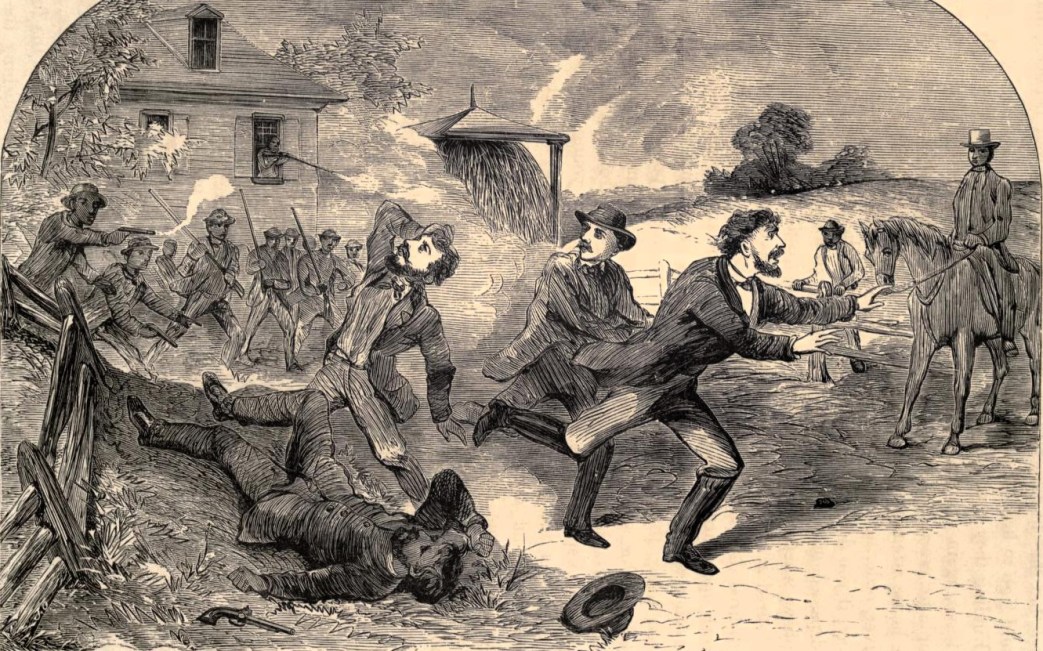

As early as 1711 we have definite records of South Carolina slaves who had run away organizing and fighting their masters.5 In New York, in 1712, an insurrection of slaves developed to such an extent that, had it not been for timely aid from the garrison, the city would have been burned. Whites were attacked in their homes and on the streets by the blacks in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1720. In 1730 many slaves in this colony actually armed and embodied to destroy the whites. Two hundred Negroes assembled near the mouth of the Rappahannock River, Virginia, to kill the white people in a church, but when the plot was discovered they fled. In 1723 some desperate Negroes planned to burn the city of Boston, and so much fear was expected that the city had to take extra precaution against “Indians, Negro or Mulatto Servants, or Slaves.” A number of Negroes arose against their masters in Savannah, Georgia, in 1728, but fled when twice fired upon, as they were already disconcerted by a disagreement as to time.

“In Williamsburg, Virginia,” according to Dr. Carter G. Woodson, “there occurred an insurrection of the blacks in 1730, occasioned by the rumor that Governor Spottswood had arrived with instructions to free all persons who had been baptized. Five counties sent forth armed men with orders to kill the slaves if they refused to submit. That year a Negro in Malden, Massachusetts, plundered and burned his master’s home because he was sold to a man in Salem, whom he disliked. In 1731 slaves being imported from Guinea by George Scott of Rhode Island asserted themselves and murdered three of the crew. Captain John Major of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in charge of a cargo of slaves, was murdered with all of his crew the following year by slaves carried on this same route. Captain Beers of Rhode Island, and all his unfortunate coworkers except two, suffered the same fate when on a similar voyage a few years later.

“In 1741 there broke out a formidable insurrection of slaves in New York City. To repress this uprising thirteen slaves were burned alive, eighteen were hanged, and eighty transported. Two of those exiled were sent to the West Indies, and it became a custom thereafter for persons having ‘any Negro men, strong and hearty, though not of the best moral character,’ to brand them as subjects of transportation to the West Indies. In 1754 C. Croft of Charleston, South Carolina, had two of his female Negroes burned alive because they set fire to his buildings. In 1755 Mark and Phillis, slaves of John Codman of Charleston, having learned that their master had by his will made them free, poisoned him that they might expedite the matter. Mark was hanged and Phillis was burned alive.

“As a sequel and a cause of the reaction came the bold attempts of the Negroes at insurrection. Unwilling to undergo the persecutions entailed by this change of slavery from a patriarchal to an economic system, a number of Negroes endeavored to secure relief by refreshing the tree of liberty with the blood of their oppressors. The chief source of these uprisings came from refugees brought to this country from Santo Domingo in 1793 and from certain free Negroes encouraged to extend a helping hand to their enslaved brethren. The first effort of consequence was Gabriel’s Insurrection in Virginia in the year 1800. It had been so deliberately planned that it was thought that white men were concerned with it, but an investigation, according to James Monroe, showed that there was no ground for such a conclusion. It was brought out, however, that these Negroes, through channels of information, had taken over the revolutionary ideas of France and were beginning to use force to secure to themselves those privileges prized by the people in that country.

“The insurrectionary movement was impeded but could not be easily stopped. At Camden in 1816, and some years later at Tarboro, Newberne and Hillsboro, North Carolina, there developed other such plots of less consequence. For some years these outbreaks were frequent around Baltimore, Norfolk, Petersburgh and New Orleans. In 1822, Charleston, South Carolina, however, was the scene of a better planned effort to effect the liberation of the slaves by organizing them to assassinate their masters. The leading spirit was one Denmark Vesey, an educated Negro of Santo Domingo, from which he had brought his new ideas as to freedom. It was observed that these Negroes in Charleston had been reading the slavery debate of the Missouri Compromise and were emboldened by the attacks on the institution to effect its extermination. In all of these cases the plans of the Negroes were detected in time to foil them, and the conspirators were promptly executed in such a barbarous way as to serve as a striking example of the fate awaiting those who refused to be deterred from such efforts.

“An extensive scheme for an insurrection, however, came in 1828 from David Walker of Massachusetts, who, in a systematic address to the slaves throughout the country, appealed to them to rise against their masters. Walker said: ‘For although the destruction of the oppressors God may not effect by the oppressed, yet the Lord our God will bring other destruction upon them, for not unfrequently will he cause them to rise up one against the other, to be split, divided, and to oppress each other, and sometimes to open hostilities with sword in hand.’

“But the most exciting of all of these disturbances did not come until 1831, when Nat Turner, a Negro insurgent of Southampton County, Virginia, feeling that he was ordained of God to liberate his people, organized a number of daring blacks and proceeded from plantation to plantation murdering their masters. Having obtained great influence over the minds of his followers, he was in a position to interest a much larger number of them than other Negroes who had undertaken to incite their fellows to self-assertion. With the aid of six desperate companions, who finally increased tenfold, he killed sixty whites. After a few days of slaughter and local warfare, Turner and his followers were finally driven into the swamps by the State militia and United States troops. On the first day over a hundred Negroes were killed. After a few days of resistance they were overpowered and imprisoned. Twelve Negroes were promptly convicted and expatriated, but Nat Turner and twenty of his accomplices were hanged. An effort was made to connect William Lloyd Garrison and David Walker with this rising, but no evidence to this effect could be found. Garrison disclaimed any connection with the insurrection. The thought then that slaves themselves could cause such a disturbance struck terror to the very heart of the South, which thereafter lived in eternal dread of servile insurrection. The slaves finally abandoned the idea of such concerted drastic action but they had already done enough to inspire John Brown for his martyrdom at Harpers Ferry in 1859.”

A.H. Gordon

NOTES

1. B.T. Washington, The Story of the Negro, Vol. 1, page 194.

2. Quoted by Weatherford, The Negro from Africa to America, page 175.

3. Woodson’s Free Negro Owners of Slaves in the United States in 1830.

4. DuBois: John Brown.

5. Holland: A Refutation of Calumnies, etc., p. 63.

The venerable ‘The Journal of Negro History’ (still publishing as The Journal of African American History), was founded in 1916 by the preeminent Black historian of his generation, Carter G. Woodson. A scholarly publication, The Journal hosted Black thinkers and histories largely shut out of the traditional U.S. left, but whose pages would deeply inform future generations of leftists and Black radicals. Carter G. Woodson, son of formerly enslaved parents who received his Doctorate in History from Harvard in 1912, founded the Association for the Study of African American Life and History in 1915 which would publish ‘The Journal’ quarterly. Woodson created what is now ‘Black History Month,’ and taught for many years at Howard University as well as being an author of a number of classic works of history. Along with invaluable early historical investigations, The Journal also carried historic documents, books reviews, conference proceedings, letters, debates, and rich contemporary social history and data. Its first decades remain an indispensable source on so much of what is now considered not just Black U.S. history, but our revolutionary history and radical traditions as well. Writers like Benjamin Quarles, John Hope Franklin, Fred Landon, W.E.B. Du Bois, Jesse Moorland, Marion Thompson Wright, John W. Cromwell, and many, many more. A essential reference of all students of U.S. history, the shaping of its politics, and the formation of its working class as it truly is.