A fascinating look at a job since transformed, but was central to communication and transport in its time. An S.L.P. telegrapher describes the history, work, conditions, and organization of his trade.

‘The Railroad Telegrapher’ by A.S.D. from The Weekly People. Vol. 13 No. 21. August 22, 1903.

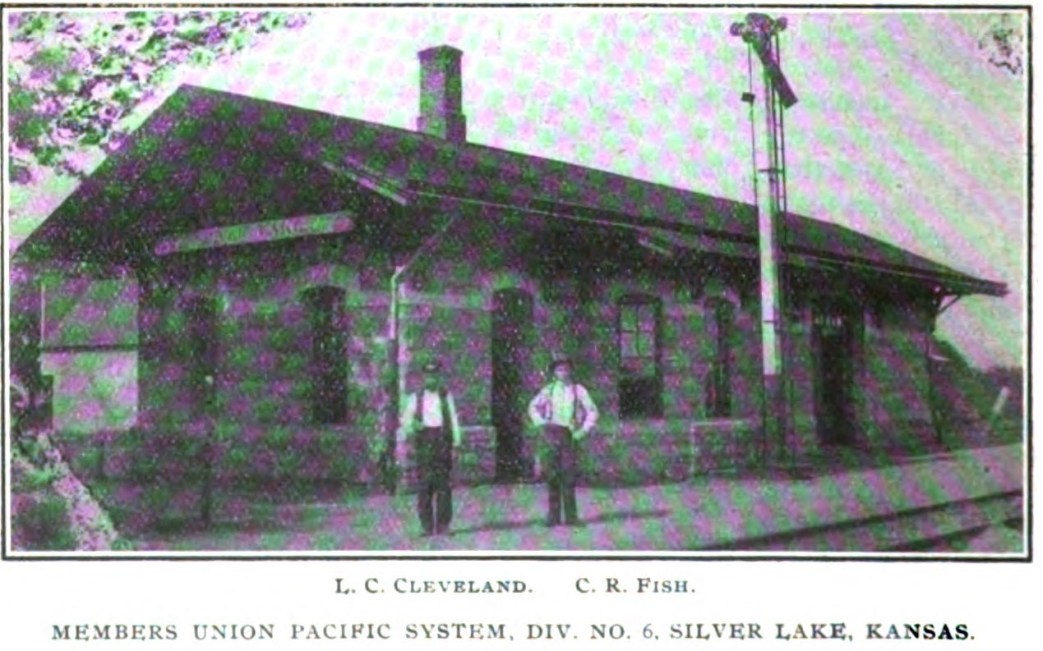

The railroad telegrapher is the eyes and fingers of the train dispatcher. Seated at his desk in the city office, or at a table in some shack or shanty on the arid plains, or amid the wind-swept Sierras, he records the flight of every passing train, checks baggage and freight, sells tickets, handles a voluminous commercial business, express and freight, loads cattle, transfers mail, cleans lamps and switch lights, advises the dispatcher as to changes in the weather, and where he is not an agent he often runs a steam or gasoline engine at pumping stations at a salary of from one-sixth to one-third that which the company formerly paid a regular pumper for this service.

These are but a part of his multifarious duties, for in order to extort dividends the corporation finds it necessary to extract most of the juice of life from its servants and wire slaves. Part of his wire work consists of train orders, car reports, messages relative to freight and the movement of the same, and the receipt and delivery of lists showing each car number and contents as it leaves each division point.

In general and relay offices a telegrapher is required to receive all messages on a typewriter, to keep same in good condition and pay for breakage. On some roads he is expected to own a machine and do the company’s work with it. At way offices, as stations outside of division points are called, these rules are not so generally enforced.

The origin of the railroad telegrapher is not far to seek–he is the product of economic necessities and conditions, and often he begins his career as a messenger boy and “swamper” around a general office or station. His gratuities at this period consisting mostly of pick-ups for special delivery of Western Union messages and possibly $15 or $20 per month on the company’s payroll. At spare moments he may copy what he can of passing messages, assist the agent or operator in making out the thousand and one reports with which the service is burdened, seal cars, take numbers, load baggage or otherwise act as a general utility man.

Some telegraphers begin as students in a telegraph school, or “ham factory,” as it is known to the initiated, but if they become anything but tyros they graduate from a railroad office. Many students part with their money and the “professor” and drift back to the farm, which is healthier though no harder than the life of the strenuous, overworked man of many responsibilities–the railroad telegrapher. When he has acquired knowledge of station work and telegraphy his sponsor, the agent or telegrapher–who is often both–recommends him to the division superintendent or trainmaster for a job. If the company is short of telegraphers, they decide to try him, and in a few days he gets a message like this:

“Jasper Johnson,

“Darktown.

“Chicago 13,

“Go to Lonelyville on No. 15 and work nights. Condr has pass.

“L. Skinner, “Supt.”

Lonleyville, like many way stations, consists of a name, a water tank, a telegraph shanty and a section house. If he can’t “batch” he boards with the section boss, and thus one more unfortunate is launched upon a catch-as-catch- can career which will land him in the president’s, or at least the general manager’s, chair.

This is the sort of inspiration he gets from the stories in the “Railroad Telegrapher,” the “Monthly (O.R.C.) Conductor.” the grafting “professors” and the capitalist press, and he believes it until he gets old enough and kicks enough to reason and think otherwise. Cold facts have a most unromantic way of knocking out capitalist sophistry and so-called wise saws, as the gray-headed old-timers in the telegraph service can testify. Several railroad systems employ from 8,000 to 25,000 men, and the Jaspers and Rubes who are eking out a sweltering existence with an eye on the presidency of “their road” have about one chance in twenty-five thousand of getting it, provided they have pull and abilities. With pull and ability they have from ten to twelve chances in twenty-five thousand of becoming division superintendent or trainmaster and drawing from $150 to $300 per month.

However, that is not the way they finish. After working nights a while a spasm of economy or a panic hits the management, and Jasper’s office is closed and he is put on the extra list to go where he is sent, to relieve some sick, discharged or leave-of-absence man for a month or two. In the course of time he may get a station at a salary that will afford him a few clothes and an occasional vacation, and just as he is settling down to the belief that he is on the sunny side of prosperity a general reorganization occurs, his salary is cut, his night telegrapher and check clerk are taken off, and he is “fortunate” in retaining his job with three men’s work to do. After working through all the various gradations of night telegrapher, check clerk, bill clerk, assistant agent, baggageman, agent and roustabout, he rounds out a quarter of a century of confining, enervating, grinding existence to find himself a broken-down, young-old man, holding down a night office at some side track, consoling himself with the thought, if he is a believer in capitalist wiseacres, that it is the identical station in life to which God in His infinite wisdom has called him.

The pay of the average railroad telegrapher ranges from $25 to $75 in the East and South to $45 and $75 in the North and West. The hours are from twelve to eighteen, varying with locations and the conditions of work. He is subject to the superintendent, train- master, chief operator, three dispatchers, auditor, traveling auditor, the express officials and the officers of the Western Union or Postal Telegraph companies. He must give a bond in a surety company prescribed by the railroad, must be familiar with a book of rules of some 150 pages, the Western Union tariff, freight, passenger and express rates and innumerable supplements and bulletins from all sources. He must neither smoke, chew, drink nor swear, must always look neat, be polite, and under no circumstances neglect the company’s interests. “Company interests” is a very elastic term, as in the case of the railroad telegrapher he is expected to act as a political agent for them when the election of a favorite candidate may be in jeopardy; to handle the tickets for the “loyal” candidates and to instruct the section foreman to see that he and his men “vote right.”

At one-man stations the railroad telegrapher has no time he can call his own, though nominally his hours are from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. There is a call bell in his office by which the dispatcher may call him at any time by making a combination similar to the following:

423217. This drops a shutter in an iron box on the telegraph table and sets the bell ringing until the telegrapher gets up and shuts it off by twisting a brass button in the end of the box. At wash-outs and wrecks his hours have no limit; he is expected to work as long as he can sit up, or until the track is clear. A hospital system is maintained on most roads, and telegraphers are required to contribute 50 cents monthly to the fund for sustaining a miserable lot of quack doctors and surgical butchers. These doctors are useful to the company in damage suits by the testimony they give. Many of the quacks are appointed solely on account of their pliability and ignorance.

I saw a striking illustration of this on the Union Pacific Railway in Montana. A boy wiper fell under an engine in a roundhouse and had a foot crushed off at the ankles. His shopmates brought him to the quack in a buggy, drawing it themselves, and the quack would have permitted him to have bled to death if one of the shopmen had not picked up and tied the broken arteries.

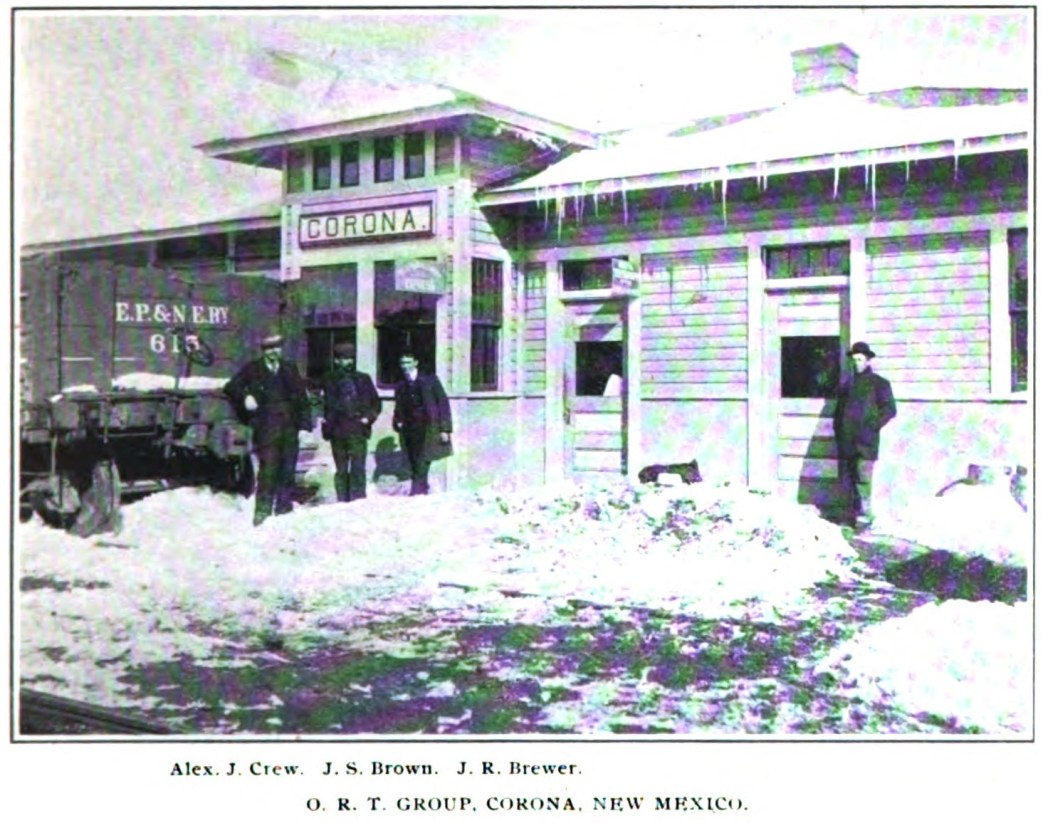

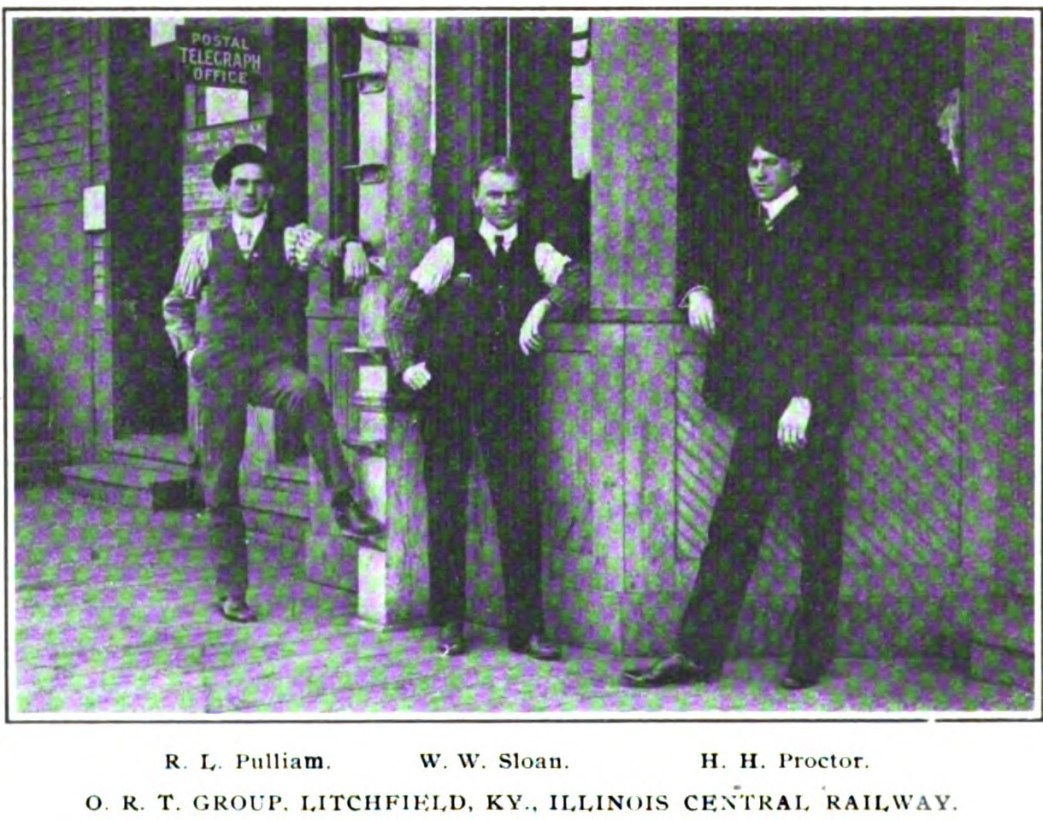

Nearly every trade has its impure and simple parasites, and the railroad telegraphers have had and are having more than their share. Just now the honors of misleading telegraph dupes are shared by “Hank,” or H.B., Perham and Geo. Estes. Perham is the president of the O.R.T., or as it is commonly known, the Order of Railroad Telegraphers, and Estes is president of the U.B.R.E., or, as it is generally known, the United Brotherhood of Railway Employes. When Estes organized the U.B. of R.E. he was general chairman of Division 53. O.R.T., on the Southern Pacific Railway system. at $250 per month and expenses, but left it for a better graft. Perham was formerly general secretary-treasurer of the O.R.T., and succeeded Humpty Dumpty, or “Mike,” Dolphin, who inherited the office of president from W.V. Powell, who was “investigated” at the St. Louis convention and kicked into outer darkness. Powell is now maintenance of way agent on the Missouri Pacific Railway and in good standing with his brother fakirs in the railway orders. Perham was a $75 clerk on the Midland Terminal Railway at Cripple Creek, Colo., shortly before he broke out as a labor (mis) leader. Now the O.R.T. pays him $3,000 per annum to dine “informally” with President Roosevelt and write Sunday school editorials on the supposed “Harmonious relations of Labor and Capital,” “A fair day’s gay for a fair day’s work,” “Labor and Capital are brothers,” etc., etc. ad nauseum. Perham expects his dupes to keep paid up and allow him to blaze the trail for the Order. He remarks that he must be very careful what he says or allows to be printed in the “Telegrapher,” even if published over a member’s own signature, for fear that the railroad officials might get offended at something and refuse to give him another schedule with its $3 “increase” and second-hand clauses copied from the company’s book of rules; hence he fills up his magazine with reprint and advertising matter furnished by the railroads, and choice recipes as to “How to make dried apple pies.”

Estes is a shrewder, smoother man than Perham, and is after bigger game. He says the railroad class orders are constantly arrayed against each other, and that they are failures. With Clark, of the O.R.C. on record as opposed to sympathetic strikes, and the different orders being constantly taught and counseled through their magazines and the capitalist press that a fellow laborer’s troubles are nothing to them, that they must maintain the inviolability of their contracts, even while the railroad companies are making ducks and drakes of said contracts, it is plain that Estes is correct. But does Estes organization offer anything better? No! It simply bunches the different departments in the B.R.E., relieves the company of their death losses by coffin assessment insurance, and sells them out collectively to capitalist politicians and capitalism. Estes, when urged by me to investigate Socialism, said he knew nothing of it, that it was an untried field to hint and he preferred to devote his time to something with which he was more familiar–the trades union movement. Then he made speeches for union labor fakirs Democratic fakirs and now I learn that his Brotherhood has indorsed the Socialist Party, which permits one to talk for any old thing or party except the S.L.P.

Blind leaders of the blind. The railroad telegrapher has a latent class-consciousness, but it is being and has always been sidetracked by labor fakirs. You talk to one of the class struggle and he assumes that you are discussing the latest brand of breakfast food or a new four-in-hand tie. The death rate among railroad telegraphers, while not as high as among commercial men, is extremely heavy, consumption having a larger per cent. of victims than all other diseases combined.

Economic development has not made such general changes among railroad telegraphers as in some other occupations, but the necessity for larger dividends is constantly spurring managers on to inaugurate a system which will give their properties greater earning capacities, and the railroad telegrapher an environment which will make him think and act along different lines than now. Then he will be ripe for Socialism and a valuable recruit for the S L.P.

New York Labor News Publishing belonged to the Socialist Labor Party and produced books, pamphlets and The People. The People was the official paper of the Socialist Labor Party of America (SLP), established in New York City in 1891 as a weekly. The New York SLP, and The People, were dominated Daniel DeLeon and his supporters, the dominant ideological leader of the SLP from the 1890s until the time of his death. The People became a daily in 1900. It’s first editor was the French socialist Lucien Sanial who was quickly replaced by DeLeon who held the position until his death in 1914. After De Leon’s death the editor of The People became Edmund Seidel, who favored unity with the Socialist Party. He was replaced in 1918 by Olive M. Johnson, who held the post until 1938.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-slp/030822-weeklypeople-v13n21.pdf