Among the earliest articles in the Socialist press devoted to the unionization of Black women, this essay by Nora Newsome is an important piece in the history of our movement. Newsome was ‘the first and only Negro woman labor organizer in the United States,’ working for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, when she wrote this for a special Women’s issue of A. Philip Randolph’s ‘Messenger.’

‘The Negro Woman in the Trade Union Movement’ by Nora Newsome from The Messenger. Vol. 5 No. 7. July, 1923.

The modern trade union movement is a product of the struggle between labor and capital. It had its rise in the industrial revolution which took place in the latter part of the 18th century. The industrial revolution introduced labor-saving machinery which was gradually concentrated into the hands of a few persons. This concentration of economic control over capital invested the owners with enormous power which they naturally employed, in obedience to their self-interest, for the exploitation of the defenseless workers, who were now gathered in what is modernly known as a factory.

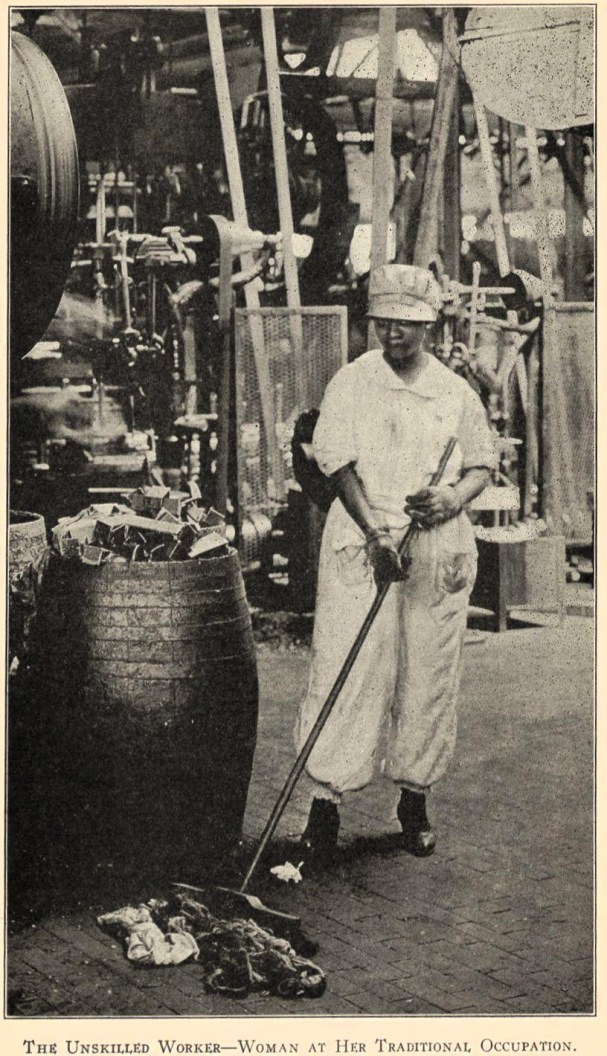

The growing refinement and specialization of machinery resulted in the partial displacement of the man worker, rendering it possible for the woman, and even the child, to compete in the factories with the men. Thus, it is clear, from a cursory survey of industrial history, that women, both black and white, have been forced to violate the proverbial dogma that “woman’s place is the home” and go into the sweat shops as the result of the iron law of economic necessity. This was no less true in America than in Europe.

In the United States the union movement is of later growth than in Europe. In that country, as early as 1348, soon after the Black Plague, workers held meetings for the purpose of fixing wages and hours. It is estimated that fifty per cent of the laborers perished in that epidemic, and this diminution in the labor supply had the effect of doubling the wages paid to the survivors. This resulted in a statute being passed by Parliament prohibiting laborers from accepting higher wages than they had been receiving before the Plague. Another statute prescribed what the workers should eat and wear, and made it a penal offense for a laboring man to eat better food or wear better clothing than that provided for in the statute.

Of course, America was not discovered until 1492, and her industrial development was, of necessity, much later than that of the Old World.

Among early labor organizations in the United States were the Caulker’s Club of Boston, organized for political purposes in the first quarter of the 18th century, and the union of bakers, which declared a strike in New York City in 1742.

Authors disagree as to the number of periods of trade union development. Richard T. Ely in his Richard T. Ely in his “Outlines of Economics” gives five periods, and Frank T. Carlton in “Organized Labor in American History” gives seven, and still others vary as to the number and sequence. I have tried to inter-relate them as follows:

(1) 1789-1825-Germinal period, which covers the history of the colonies, and of the first fifty years after the Declaration of Independence, and is our prefatory stage of industrial development. Labor organizations are found only in the latter portion of this period, and these consist of only a few local and temporary trade societies.

(2) 1825-1837- Revolutionary Period. The introduction of the American factory system, which ushers in an epoch of extraordinary and premature organization of labor; close connection between trade unionism and more radical reforms, such as socialism and co-operation.

(3) 1838-1857-Period of Humanitarianism.

(4) 1859-1873-Civil War Period.

(5) 1876-1895-Federation Period. Characterized by the enlargement of business; unusual middle class agitation, the rise and decline of the Knights of Labor, the first successful general organization in the United States, and the birth of the American Federation of Labor in 1881.

(6) 1896-1923-Period of Collective Bargaining; so-called because of the rapid expansion of unionism, and the establishment of new national or district systems of collective bargaining after the industrial depression of 1893-1897; and because it is only in recent years that employers and the general public have recognized the fact that trade unionism is here to stay, and must be regarded as a permanent institution with which many employers of labor must bargain, whether they like it or not.

The trade union movement is bringing to the woman worker an immeasurable degree of economic independence, without which she is the natural and inevitable victim, the uplift Christian reformers to the contrary notwithstanding, of the necessity to barter her honor for gain. This is all the more obvious to modern psychological sociologists, who are beginning to see that the irresistible force of the “social me” drives the woman to fight, not only for the acquisition of necessities, but also for the satisfaction of her higher wants, or what is more euphemistically and reproachfully known as vanity.

The first American crusade against low wages for women was carried on by Matthew Carey, a Philadelphia publisher, from 1828 to the time of his death in 1839. In 1830, Carey estimated that there were between 18,000 and 20,000 “working women” in the four cities of New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Baltimore. “At least 12,000 of these,” he said, “could not earn by constant employment for 16 hours out of the 24, more than $1.25 per week.” Think of it! Matthew Carey also believed that there was a direct relationship between low wages and prostitution.

It is interesting to know that he offered a prize, valued at one hundred dollars, for the best essay “on the inadequacy of the wages generally paid to seamstresses, spoolers, spinners, shoe binders, etc., to procure food, raiment and lodging; on the effect of that inadequacy upon the happiness and morals of these females and their families, when they have any, and on the probability that these low wages frequently force poor women to the choice between dishonor and absolute want of common necessities.” Note that he said “common necessities” and not luxuries. This prize was won by a well-known social worker of that period, Rev. Joseph Tuckerman.

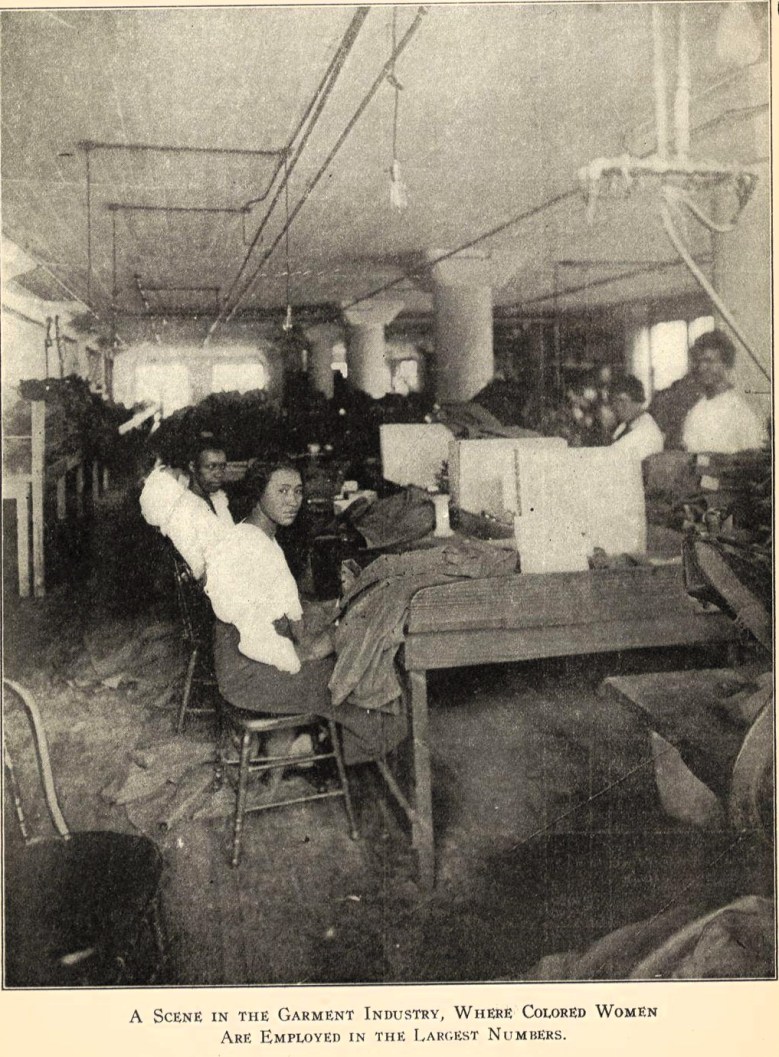

One of the most formidable trade unions of today is the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, which is composed of workers in the men’s garment industry. It consolidated these workers, who had been most brutally exploited in the sweatshops, into one of the most aggressive and progressive organizations known in the labor movement. As an evidence of its foresight and policy of fair dealing, the Amalgamated has been the first union to put on a colored organizer, because it realizes that the most vital necessity exists for the organization of Negroes in industry into trade unions.

When I first reported to the business manager of the local for which I was to start organizing, he seemed a bit skeptical about my getting results. This local has an Italian organizer who had been sent to talk to the girls, both colored and white, in the open shops. The majority of the colored girls would not even listen to his arguments in favor of unionism, and the others would listen courteously but remain unorganized. I told this official that Negroes bitterly distrusted white people and had no faith in their promises, and that they could not reasonably expect to eradicate in one day, a week, or even a month, the impression that centuries of cruel treatment had created in the Negroes’ minds. Of course, the A.C.W.A. has never discriminated against Negroes in its entire history, but they do not know that. To them it is simply a union, and they do not possess the necessary knowledge to discriminate between the good and bad unions.

I have been quite successful from the very beginning. The girls, almost without exception, have received me courteously and listened attentively to what I had to say. Several expressed themselves as being pleased that a colored woman organizer had been sent to talk to them, and voiced a dislike for men organizers. They felt, and rightly so, that a colored woman knew more than a white man possibly could about the specific ills from which their group suffered. Of course, there are certain generalizations that hold true and are applicable to both black and white alike. but the white has never been proscribed and denied the right of opportunity in industry as has the Negro. Some of the girls were anxious to join the union and said they were glad I had been sent to them; that they knew union members received higher wages, and worked shorter hours under better conditions. One girl told me she wanted to join the union because the foreman in her shop would not let the colored girls do piece-work. They are compelled to work for a flat salary of $17.00 or $18.00 a week, whereas, if they did piece-work, in an open shop, they would make from $25 to $30. The union wage for the same work is at least $40.00. The white pressers, mostly Italian men, in this shop, do piece-work because they are organized and would not work there at all unless they did. The foreman, being non- union, is on the side of the employer, and if he can force the twelve colored pressers in his shop to work for $18.00 a week when they could make $30.00, he has saved $144.00 a week for the boss. By the union standard he has saved at least $264.00.

On the other hand, some of the workers fear that they might lose their jobs if it came to the ears of their employer that they had joined the union; others fear the loss of wages through strikes. I point out to them that if they lose their jobs because of joining the union, we find other jobs for them in union shops. When we organize a shop, our representative calls on the owner and informs him that he must institute union conditions and wages in his shop. If he agrees, very well; if he refuses, we call a strike, and if the strike lasts over a period of weeks, we pay benefits to the strikers, if we cannot find suitable jobs for them. After all, they usually see that they have everything to gain and nothing to lose by coming into the union.

I find a disposition on the part of owners of open shops to employ more colored girls than white because the colored girls are usually unorganized and consequently work for lower wages. Then, too, some bosses pay the prevailing union wage in their fight to maintain the “open shop” in order to discourage workers from joining the union and fighting for increases.

Many of the girls possess a high degree of intelligence—indeed, many of them have a high school education for a job which requires no special education whatever. Of course, that is because the opportunity to learn the skilled branches of the trade as apprentices has been denied to them because of color, and they must, perforce, become pressers or not work at all. The A.C.W. of A. has the record of only one colored girl who was employed as an operator. She was discharged by the boss on account of color, and immediately all the white operators went on strike and forced him to reinstate their colored comrade.

One afternoon, while I was waiting for the girls at closing time, a white girl was distributing circulars to employees of another shop in the building. The circulars were not sent out by our union, but I wanted to know, for general information, what they contained, so I asked for one. As I was reading it, a policeman came up and told me that I could not distribute circulars around there. I replied that I could not possibly be distributing them when I possessed only one, and that that one was for my personal satisfaction. I stayed where I was and talked to the girls as they came out of the building, but he did not trouble me again.

Some elevator operators, both white and colored, have co-operated with me splendidly in my organization work. They can render assistance in several ways, such as identifying the workers of a particular shop, the employer, the foreman, whether the girls go to lunch, and all that sort of thing.

One factor that retards the organization of colored workers is their migratory tendency. They are constantly changing from one job to another. With each successive change, they hope to find something better than they left behind; a mute expression, as it were, of the eternal desire of the human heart.

Organization into trade unions will usher in a new day for the Negro woman worker. Her economic problem arises from her ignorance of economic values, and from the exploitation to which this ignorance subjects her. The social pressure, which confines them to the most unskilled and low-grade occupations, most of which do not tend to uplift or develop them, is deadening, and the labor movement, as such, can never achieve the goal for which it is striving while its colored component is like the “Old Man of the Sea” on its back, because it is denied the opportunity to attain the heights aspired to by the other group.

Unionism, perhaps more than any other agency, will do much toward cementing the relationship between white and colored workers. When white and colored men and women meet on an equal basis in the workroom, fight together for their common betterment, and together bear the suffering resulting from that fight, I cannot possibly see how they can hate each other in the class room, restaurant, theatre or any other place where social intercourse is desirable.

The labor movement offers a glorious opportunity to young colored women of education and ideals to give creative, constructive service to the Negro race in particular, and the workers in general. Ever since my emancipation from the fetish of white collar supremacy and intellectual aloofness, I have yearned to become one of that steadily increasing number who, by means of voice and pen, are trying to hasten the dawn of a new day for the world’s producers.

There is no data available on Negro women in the trade unions because they are not listed as such, and I have presented only the matter coming within my own experience as organizer for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America.

The Messenger was founded and published in New York City by A. Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen in 1917 after they both joined the Socialist Party of America. The Messenger opposed World War I, conscription and supported the Bolshevik Revolution, though it remained loyal to the Socialist Party when the left split in 1919. It sought to promote a labor-orientated Black leadership, “New Crowd Negroes,” as explicitly opposed to the positions of both WEB DuBois and Booker T Washington at the time. Both Owen and Randolph were arrested under the Espionage Act in an attempt to disrupt The Messenger. Eventually, The Messenger became less political and more trade union focused. After the departure of and Owen, the focus again shifted to arts and culture. The Messenger ceased publishing in 1928. Its early issues contain invaluable articles on the early Black left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/messenger/v5n07-jul-1923-Messenger-riaz-fix.pdf