The coming ‘Labor Day’ holiday was a necessary consolation prize given to the working class by President Cleveland’s administration facing midterm elections after smashing the Pullman strike in 1894. One of the key strikes in U.S. labor history, the consequences of which are lived with by the labor movement to this day, it was led by Eugene Debs and the American Railway Union. Justus Ebert tells the story for a special rail workers edition of ‘Solidarity.’

‘The Chicago Strike of 1894’ by Justus Ebert from Solidarity. Vol. 7 No. 352. October 7, 1916.

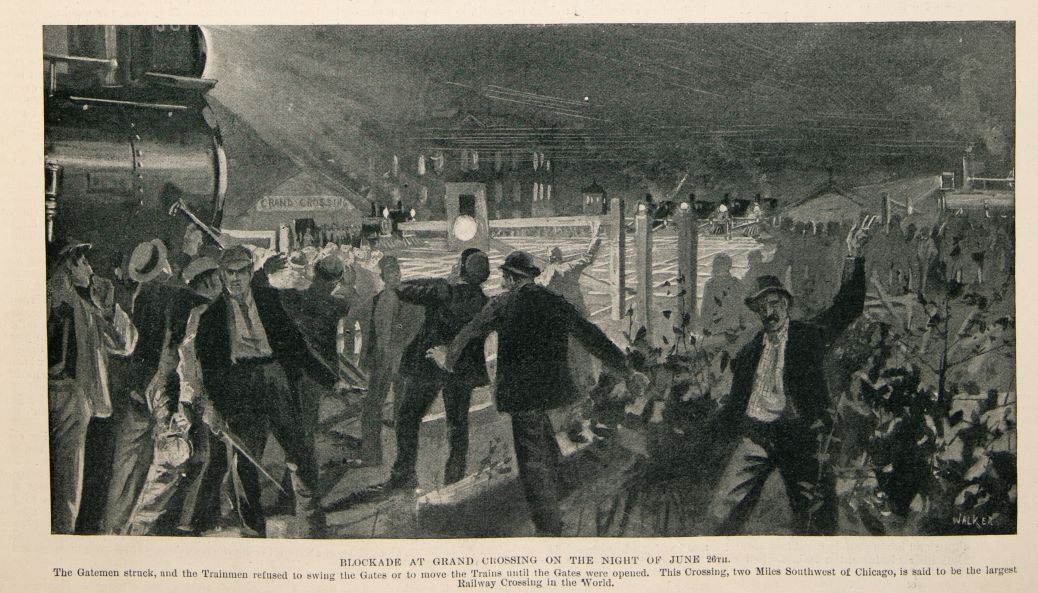

On June 26, 1894, this country was taken by surprise, when Chicago despatches announced that the American Railway Union had placed a boycott upon the Pullman palace cars used on most of the railroads of the country. Few understood the significance of the announcement. But subsequent events showed it to be a most important one, provocative of one of the biggest railroad upheavals in the country; and incidentally demonstrated the wrong organization of railroad labor.

The American Railway Union was a young body. In April, 1894 it had fought a successful strike on The Great Northern Railroad against a ten per cent reduction. This strike lasted a fortnight and involved 5,000 employes on 3,700 miles of railroad and paralyzed business over a wide region. This gained the new organization thousands of members.

The American Railway Union was the conception of Eugene V. Debs, who had up till then been an organizer, orator and editor for the Locomotive Firemen and its magazine. Debs recognized the failure of the five old organizations of railroaders–the engineers, the conductors, the switchmen, the firemen and the trainmen, besides the shop employes. They had failed to act harmoniously. One of them was “played off” against the other to the ultimate disadvantage of all. It was Debs’ aim to make the interests of one branch of railroad service the concern of all. His American Railway Union was to embrace all branches of the service. That the new union was needed was shown by the way that multitudes of railway workers joined it. Debs was its first president, with Sylvester Howard as first vice president. Debs and Howard desired, in addition, a practical alliance with all labor bodies, and had held a conference with a number of them at St. Louis in June, 1894.

The week before the boycott had been declared, the American Railway Union in convention assembled at Chicago, had listened to a statement of grievances presented by the workmen of the Pullman Company, located in that part of Chicago bearing the same name. Several thousand of them had been on strike against bare-subsistence wages and an infamous company system, for the Pullman Company was a paternalistic company, far in advance of many corporations of today, Pullman treated his employes with contempt. When asked by the American Railway Union to arbitrate the strike, he said, “There is nothing to arbitrate,” showing a clear-headedness and candor remarkable in a capitalist of that time. Thereupon, the boycott was levied as a last resort.

Work was stopped on every line that used the Pullman cars.

The spread of the strike was something amazing. It paralyzed the whole railroad system west of Chicago. From every quarter of 20 states came a decided response that tied up the railroads tighter than a drum. Says John Swinton, in his “Momentous Question,” which gives come of the best chapters ever writ ten on this great strike: “The Southern Pacific Company could not move a wheel; all California was train-bound; the Santa Fe road was tied up; northward as far as Montana transportation had been brought to an end.” The Eastern states were greatly affected. Everywhere there were great waves of enthusiasm in behalf of the strike. One hundred thousand railroaders were believed to have taken part in it. One hundred and fifty thousand unionists in Chicago were ready for a general strike if necessary. The working railroaders in the Eastern and Southern states of the country held aloof from the strike because of the overshadowing influence there of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and the A.F. of L. leaders, under the guidance of Sam Gompers. This last worthy could not be found for the first three days of the strike, and when found his conservatism was such as to throw the weight of A.F. of L. influence against the strike. In the St. Louis Fair Handbook, the A.F. of L, over Gompers’ signature, commends itself to the capitalists because of the great services it had rendered the country in connection with the railroad brotherhoods, in the Chicago railroad strike of 1894. But even they kick its disorganization when they can, such is their lack of gratitude for traitorous conduct.

Another factor that contributed to the defeat of the strikers was the interference of the Cleveland administration. It sent troops to Chicago to crush the strikes, at the solicitation of the General Managers’ Association and over the protests of Governor Altgeld, who denied the necessity for such drastic action. Swinton intimates that agent provocatuer furnished the excuse by burning cars, tearing up rails and derailing trains. Between the Brotherhoods, Gompers and the Cleveland administration, Debs was beaten. They wanted none of his one union of all the railroad workers, as that would have destroyed the separate brotherhoods and the craft organizations of the A.F. of L., besides enabling the working class to present a united front to capitalism. It is doubtful if the Federal troops could have crushed the American Railway Union without the aid of the Brotherhoods and Gompers. Debs and Howard were jailed. In jail Debs became a political socialist. He permitted the political mirage to hide the lessons of his great economic effort. His resort to political agencies was as suicidal as that of the Brotherhoods is now likely to prove to be to them.

Though Debs was crushed by craft division, federal interference and political delusions, the spirit of the American Railway Union was subsequently revived by George Estes in the formation of the Brotherhood of Railroad Employes And now it finds expression again in Local 600 of the Railroad Workers’ Industrial Union of the Industrial Workers of the World, of which the Brotherhood of Railway Employes was a part at the time of its organization. Evolution evolutes, for the industrial forces are with it. J.E.

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1916/v7-w352-oct-07-1916-solidarity.pdf