In many places across the country the only public art (where it has yet to be destroyed) remains that created in the 1930s under various New Deal projects. Among the leading Marxist art critics and historians of the 20th century, Meyer Schapiro’s fascinating essay on how to engender support for codifying public arts programs, as public schools and libraries were, brings out larger questions concerning relationship between state and art, the artist and the public, and workers and art. Stimulating.

‘Public Use of Art’ by Meyer Schapiro from Art Front. Vol. 2 No. 10. November, 1936.

THE present art projects are emergency projects and therefore have an obvious impermanence. It is possible that after the national elections an effort will be made to curtail them or to drop them altogether.

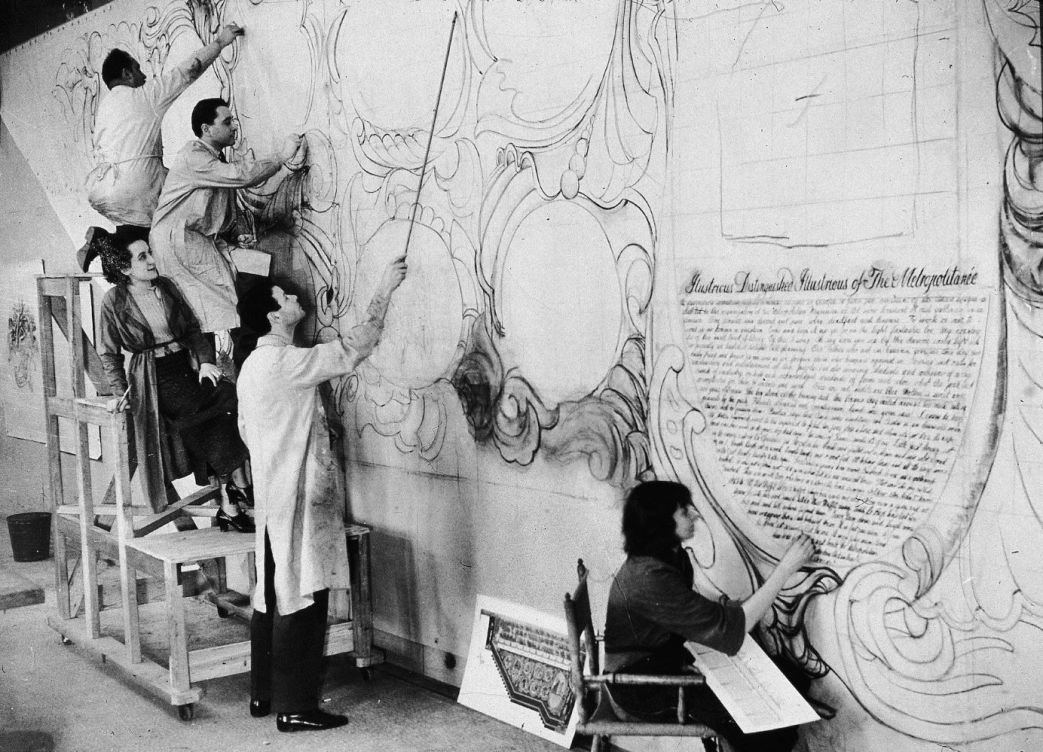

To the artists, however, the projects constitute a remarkable advance. For the first time in our history the government supports art, assigns tasks to painters, sculptors, graphic artists and teachers, or accepts their freely created work, and pays a weekly wage. The projects may be limited and the conditions poor, but the whole program is an immense step toward a public art and the security of the artist’s profession.

What can artists do to maintain these projects and to advance them further toward a really public art?

It is the common sentiment that with the support of the organized working class these projects can be maintained. The art projects are parts of a larger government program which embraces many groups of workers, and the artists as workers can rely on the support of their fellow-workers, who will second their demands. But the interests of artists and industrial workers are not identical in this matter today. The industrial workers wish to return to regular and full employment and to obtain social insurance; the government projects and relief often reduce them to the status of unskilled labor and establish a wage far below the older union scale. The artists on the other hand would rather maintain the projects than return to their former unhappy state of individual work for an uncertain market. Even during the period of prosperity artists were insecure; now during a general crisis they are, for the first time, employed as artists. Workers and artists are not of one class or role in society. Artists are usually individual producers. They own their tools and materials and make by hand a luxury object which they peddle to dealers and private patrons. They employ an archaic technique and are relatively independent and anarchic in their methods of work, their hours of labor, their relations with others. Under government patronage they acquire a common boss, they become employees or workers, like the teachers and postal employees. But they are not yet really employees of the government, they are simply on emergency projects.

If conditions improve and the great mass of unionized workers are re-employed, what immediate interest will they have in demanding that one small group of temporary government employees, engaged in decorating buildings, should be kept permanently on the national payrolls, especially when the majority of workers have no assurance of permanent employment? Unlike the postal workers and the teachers, the artists do not satisfy a universally recognized need; their services are not available to everyone.

The possibility of working class support depends on the recognition by the workers that this program of art has a real value for them. It depends further on a solidarity of artists and workers expressed in common economic and political demands.

We can learn from the example of the architects. It is also in the interest of the architects to demand permanent government employment. But how can the government employ them? Chiefly by setting up permanent national housing projects, and projects for schools, hospitals and places of recreation. Now such projects, if designed to reach the workers, will have the support not only of the building workers, but of all workers, since they are poorly housed, and feel the urgent need of such construction. The workers will therefore support the architects in their fight, since the demands of the architects are also important demands. of the workers.

We have also the example of the teachers and free education. Public schools were won by the persistent struggles of the workers and the Mechanics Societies of the last century; they were not simply presented to the people by a generous and enlightened state. The upper classes opposed them on the ground that free education would give the workers dangerous ideas. The workers demanded free schools precisely because schooling enabled a worker to read and write and to learn about the world; he could then defend his own interests better, form his own organizations, and judge more critically the dogmas of the church and the ruling class. But once the schools were established and the teaching was directed more and more toward fixing the workers’ mentally along lines favorable to the ruling class, the teacher felt himself to be socially superior to the worker and alien to him. It was only when teachers showed their interest in the working class and its children, fought in the same struggles, united their organizations, challenged the school boards and legislatures in behalf of educational progress, that workers could be aroused to support the teachers in their special demands for better wages and conditions and for academic freedom.

It is necessary then, if workers are to lend their strength to the artists in the demand for a government-supported public art, that the artists present a program for a public art which will reach the masses of the people. It is necessary that the artists show their solidarity with the workers both in their support of the workers’ demands and in their art. If they produce simply pictures to decorate the offices of municipal and state officials, if they serve the governmental demagogy by decorating institutions courted by the present regime, then their art has little interest to the workers. But if in collaboration with working class groups, with unions, clubs, cooperatives and schools, they demand the extension of the program to reach a wider public, if they present a plan for art work and art education in connection with the demands of the teachers for further support of free schooling for the masses of workers and poor farmers, who without such public education are almost completely excluded from a decent culture, then they will win the backing of the workers.

But to win and keep this support, the artists–for the first time free to work together and create for a larger public– must ask themselves seriously for whom they are painting or carving and what value their present work can have for this new audience.

The truth is that a public art already exists. The public enjoys the comics, the magazine pictures and the movies with a directness and whole-heartedness which can hardly be called forth by the artistic painting and sculpture of our time. It may be a low-grade and infantile public art, one which fixes illusions, degrades taste, and reduces art to a commercial device for exploiting the feelings and anxieties of the masses; but it is the art which the people love, which has formed their taste and will undoubtedly affect their first response to whatever else is offered them. If the artist does not consider this an adequate public art, he must face the question: would his present work, his pictures of still-life, his landscapes, portraits and abstractions, constitute a public art Would it really reach the people as a whole?

If the best art of our time were physically accessible to the whole nation, we still would not have a public use of this art. To enjoy this art requires a degree of culture and a living standard possessed by very few. Without these a real freedom and responsiveness in the enjoyment of art is impossible. We can speak of a public and democratic enjoyment of art only when the works of the best artists are as well known as the most popular movies, comic strips and magazine pictures. This point cannot be reached simply by education, as the reformers of the nineteenth century imagined. It is not a matter of bringing before the whole people the objects enjoyed by the upper classes (although that too must be done). These pictures and statues are almost meaningless to the people; or they have the distorting sense of luxury-objects, signs of power and wealth, and are therefore appreciated, not as art, but as the accompaniments of a desired wealth or status. The object of art becomes an instrument of snobbery and class distinction. Art is vulgarized in this way and its original values destroyed. The abominable and pathetic imitations of upper-class luxury sold to the workers and lower middle class in the cities are often products of this teaching. The plans to improve the industrial arts, to produce finer house ware, textiles and furnishings for the people run into similar difficulties. And as long as the income of the masses is so small, as long as the majority do not have the economic means to recreate their own domestic environment freely, such improvement of the industrial arts affects only a small part of the people. The very limitation of the market finally hampers their growth.

The achievement of a “public use of art” is therefore a social and economic question. It is not separate from the achievement of well-being for everyone; it is not separate from the achievement of social equality. The very slogan “public use of art,” raised in opposition to the limited and private use of art, attests to the present inequality. From this inequality flow many of the characteristics of both the private art and the commercialized public art. To make art available to everyone the material means for diffusing the degraded contemporary art, the printing presses and the admirable techniques of reproduction, must become the vehicles for the best art. But these today are commercialized; they are private property, although created and rendered productive by the labor of thousands. When they become public property, the antagonistic distinction between public and private in art must break down. Art would be equally available to everyone; you should be able to buy a print or a faithful replica of the best painting as you buy a book or a newspaper.

Before the levels of art which the artist values can become available to the masses of people, two conditions must be fulfilled that the art embody a content and achieve qualities accessible to the masses of the people, that the people control the means of production and attain a standard of living and a level of culture such that the enjoyment of art of a high quality becomes an important part of their life.

The two conditions are not entirely distinct. The steps toward the first are part of the larger movement toward the second. And since the latter exerts a powerful influence on the imagination of artists, it inevitably reacts upon art.

To create such a public art the artist and as an artist; he must become realistic must undergo a change as a human being in his perceptions, sympathetic to the people, close to their lives, and free himself from the illusions of isolation, superiority and the absoluteness of his formal problems. He must be able to produce an art in which the workers and farmers and middle class will find their own experiences presented intimately, truthfully and powerfully. The shallowness of the present commercialized public art would then become apparent.

On the other hand, the masses of the people must control production before they can control their own lives; they must win a genuine social equality before culture can be available to everyone. Only free men who have power over their own conditions of life can undertake great cultural plans.

The artists who identify themselves with the workers in the struggle for this change, who find in the life and the struggles of the workers the richest matters for their own art, contribute to the workers a means for acquiring a deeper consciousness of their class, of the present society and the possibilities that lie before them, a means for developing a readier and surer responsiveness to their experiences, and also a source of self-reliance. The workers discover through art a whole series of poetic, dramatic, pictorial values in the life of labor and the struggle for a new society which the art of the upper classes had almost completely ignored. In strengthening the workers through their art, the artists make it possible for art to become really free and a possession of all society.

Now it may seem to some of you that this talk of socialism has carried us too far from the present program, that we ought simply to stick to our demand that the government extend the art projects to reach a wider public. I think this is a serious mistake. The artists must look beyond their immediate needs plans for a public use of art. They might obtain many concessions from Washington and win the support of large and influential groups of workers, and yet be no better off in the long run, perhaps much worse. Even if in cooperation with the unions they begin to decorate the walls of union houses and the homes built for workers with government subsidy, they may find themselves without means of work or dependent on a brutal fascist regime.

The powerful unions in Germany were smashed by Hitler and their fine buildings confiscated. In Italy, while wages are being cut and the people marshalled for the battlefield, artists are employed by the fascist regime to decorate the walls of the government unions with frescoes showing dignified, massive laborers heroically and contentedly at work.

Government support of art, the cooperation of labor unions and artists, does not in itself solve the insecurity of the artist. They may provide a temporary ease and opportunity for work, but the unresolved economic crisis will soon grip the painter again.

More important, this government patronage and this cultural cooperation with the unions may divert the attention of the artist and the members of the unions from the harsh realities of class government and concealed dangers of crisis, war and progress and fascist oppression. Artistic display is a familiar demagogic means; the regime which patronizes art confirms its avowals of peace and unprejudiced concern with the good of the people as a whole. In 1764 after the ruinous Seven Years’ War, the artistic adviser of the French king recommended that he decorate his new palace with paintings illustrating royal generosity, love of peace and concern for the goddesses. Today this choice does not exist. A regime that must hold the support of the people today, provides conventional images of peace, justice, social harmony, productive labor, the idylls of the farms and the factories, while it proposes at the same time an unprecedented military and naval budget, leaves ten million unemployed and winks at the most brutal violations of civil liberty. In their seemingly neutral glorification of work, national history, these public murals are instruments of a class; a Republican administration would have solicited essentially similar art, though it might have assigned them to other painters. The conceptions of such mural paintings, rooted in naive, sentimental ideas of social reality, cannot help betray the utmost banality and poverty of invention.

Should the artist therefore abandon his demand for government support of art? Not at all. He must on the contrary redouble his efforts to win this demand, since the government project is a real advance. But he must develop in the course of his work the means of creating a real public art, through his solidarity with the workers and his active support of their real interests. Above all he must combat the illusion that his own insecurity and the wretched state of our culture can be overcome within the framework of our present society.

Art Front was published by the Artists Union in New York between November 1934 and December 1937. Its roots were with the Artists Committee of Action formed to defend Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads mural soon to be destroyed by Nelson Rockefeller. Herman Baron, director of the American Contemporary Art gallery, was managing editor in collaboration with the Artists Union in a project largely politically aligned with the Communist Party USA.. An editorial committee of sixteen with eight from each group serving. Those from the Artists Committee of Action were Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Zoltan Hecht, Lionel S. Reiss, Hilda Abel, Harold Baumbach, Abraham Harriton, Rosa Pringle and Jennings Tofel, while those from the Artists Union were Boris Gorelick, Katherine Gridley, Ethel Olenikov, Robert Jonas, Kruckman, Michael Loew, C. Mactarian and Max Spivak.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/art-front/v2n10-nov-1936.pdf