The industries may have changed, but the structure in small-town America has not; petty local capitalists acting as lords fostering communities of ignorance, despair, and reaction. Here, David Coutts looks at Muscatine, Iowa that, like so many of these fiefdoms, also has a counter, radical, past.

‘Middle Western Feudalism’ by David Coutts from The Daily Worker Saturday Supplement. Vol. 2 No. 65. March 28, 1925.

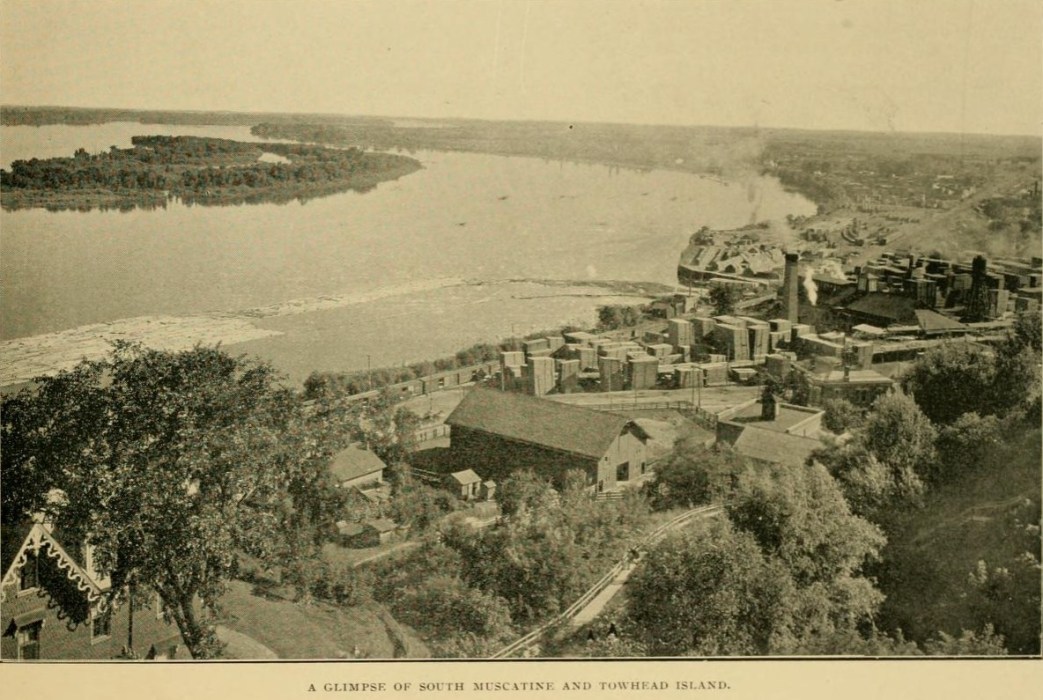

MUSCATINE, IOWA. THIS town is the graveyard of craft unions and hopes of the workers. Following the button workers’ strike fourteen years ago the spirit of Muscatine died. At that time little business started in friendly to the strikers, but as soon as the factory owners brought in gunmen and militia little business changed front.

They wanted law and order, peace and harmony; so the strike was lost after twelve months of battling. The workers were defeated in a decisive battle and reduced to a state of serfdom. Little business has had to give up its “independence” and become the vassal of the millionaire owner of Muscatine.

THE button workers defeated the first attempt to use gunmen to protect strikebreakers. The thugs were driven into a hotel and surrounded, and only the pleadings of the “best citizens” saved them. They were allowed to depart, only to return later with three times the force. This aroused the entire town and the national guard was called out to protect “law and order.”

Apparently the spirit of the strikers could not be broken from without. They then resorted to the tactic of the French socialist, Briand, they called the strikers to the colors in the national guard to break the spirit I of their own strike. Most of the guardsmen were button workers.

Since the strike there has been no organization whatever in the button factories.

Lumber Baron’s Empire.

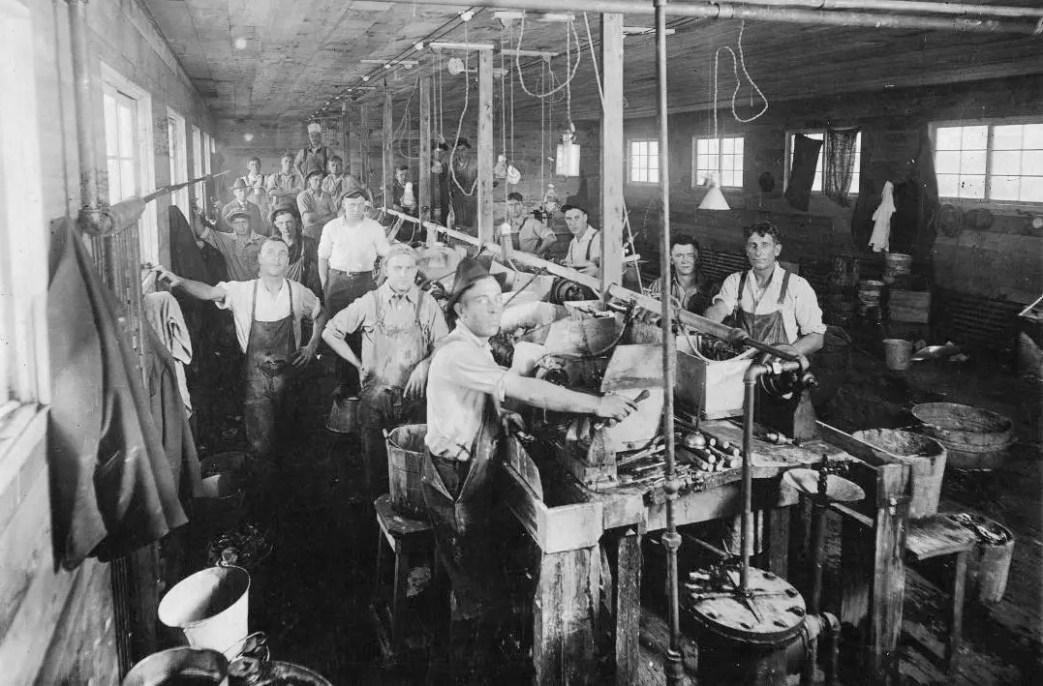

THERE are six button finishing and about twenty button cutting plants in Muscatine. Some of the finishing plants also have cutting departments. Button cutting plants are being placed in the little hamlets in the country and the farmer and his boys are doing the cutting when he is not working sixteen hours a day on his rented acres.

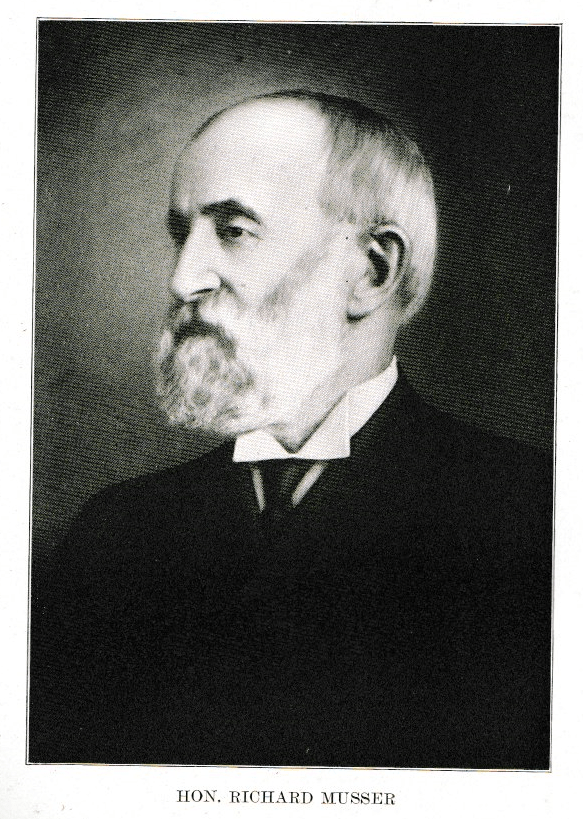

In the early days of Muscatine, old man Musser owned a lumber yard and prospered. He soon blossomed, out into a lumber baron, owning forest tracts and sawmills, and during the war got mixed up in some deal to grab forests and was “investigated” by the government. Old man Musser left his son a lot of millions and the baronetcy of Muscatine.

TODAY young Musser is said to be worth a hundred million. He owns two or three button factories, two large sash and door factories, a number of banks and forty per cent of the business men have got to “see” him to do business.

Old man Musser was “good” to the town and gave a library, public park and other trinkets to decorate his domain. Needless to say that panels bear his name in big letters to show the “beneficence” of the departed master.

“Sweating System” for Slaves.

THE men and women employed in sash and door factories work nine hours per day, 5 1/2 days per week, for from $12.40 to $19.25. In the button factories the average wage for a week of fifty hours is $14.50. Beginners get $2.50 per day.

About two weeks ago an expert button cutter, who has been following this work for over twenty years, got $12.85 for fifty hours work. Another good button cutter got $18.00 for a full week and had a family of four to support. A very few of the younger men, by maintaining terrific speed, make up to $25.00 for a full week. This is all piece work and prices are cut every time orders fall off, which appears to be often now. A gross of buttons in Muscatine is 168 at the factory and all breakages count against the worker.

Women make as much as some of the men. They, too, work piece work, sewing buttons on cards at two cents a gross.

AS soon as children get big enough they are forced into the factories to add to the family wage. With the cost of necessities high in Muscatine the slaves cannot even afford a ten-cent movie.

“American Peasants” Cut Wages.

There are many small farmers around Muscatine. They come to “town” every Saturday and stand around on “Main Street” visiting. They also come in during the winter to cut buttons, or to cut ice, ten hours a day at $2.25 to $2.50.

In order to reduce the workers and farmers still further these small plants are being placed out in the country, where the farmer can cut buttons for the boss two or three days and then work on his rented or mortgaged acres the other part of the week. Or he may work full-time during the winter months in the factory. In this way the wages are kept down to the lowest, the farmer having his house and much of his own food, will work cheap.

To understand the small farmer’s situation: He is a relic of the individualistic, “land and liberty” age. He knows nothing of hours, wages, organization or working conditions. The only money he ever sees is the few dollars he gets for butter or eggs. His other products are mortgaged and transferred by check to the banker. Even $2.00 for ten hours looks big to him with his simple needs supplied in great part from his land. So the slave drivers in Muscatine are using the peasant to beat down the proletariat in the city.

Kluxers, Socialists and Rubber Tired Farmers.

IN spite of the small wages depriving them of the movies, hundreds of the slaves and small business men joined the klan. The organizer got from three to four thousand dollars for membership fees at $10.00 each. The klan is now on the decline and will soon be history in Muscatine. Mr. Gladstine, a Jewish gentleman who owns one of the largest dry goods stores in town, is trying to collect for a lot of material sold to the klan during its days of prosperity.

A number of the socialists, who could not afford to pay twenty-five cents a month dues to the party, out of their small wages dug up $10.00 to help the klan save the country. The present mayor was elected on the republican ticket, which was the klan ticket. He was formerly a member of the socialist party, then flirted with the democrats before joining the klan and the republicans.

THE socialists have had a local in South Muscatine for many years. This suburb is about two miles out, a working class section to which no attention is ever paid. There is no side-money in the job of alderman. The socialists have wanted a sewer system there for the past twenty years.

They got it all “fixed” once, but a petition was circulated which was signed generally and shelved the proposition. They have elected their socialist alderman regularly and this goes to show the outside world that Kaiser Musser of Muscatine loves his socialists.

There are many retired farmers, “Rubber Tired,” Dad Walker calls them, living in Muscatine. The residential section has the appearance of prosperity, with good houses on paved streets. Bond issues for paving or sewage in the working class districts are generally defeated by the self-satisfied, retired farmer.

Labor Union “Ghosts.”

THERE is a carpenters’, bricklayers’ and street carmen’s local in Muscatine. The Typographical Union, electrical workers and barbers also have a few members. A member of the Typographical Union writes about two columns a week for the local capitalist daily, which, although it is apparently honest, lacks even a semblance of inspiration.

There is an atmosphere of hopelessness among the workers which gives these little locals the appearance of ghosts. They are the symbol of the vanishing spirt of what was once the scene of a decisive battle.

Throughout Iowa, and especially in towns like Muscatine and Marshall town, there is a big task before the Workers Party and the trade union movement. First to revive the hope of a small militant minority and organize them into the party. Then follow this up with an intensive organization drive for the labor unions, making it a concerted, united campaign to sweep every worker into the union. To overcome the power of the feudal baron this movement must take on the appearance, it must actually be a revolt, a rebellion against the intolerable conditions now being imposed upon the workers.

THESE small towns are a vast reservoir for scabs and strikebreakers. They must be educated and organized, or their 100 per cent psychology will be used to crush the rising spirit of the city workers everywhere. A united front for an attack on ignorance is needed.

The Saturday Supplement, later changed to a Sunday Supplement, of the Daily Worker was a place for longer articles with debate, international focus, literature, and documents presented. The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1925/1925-ny/v02b-n065-supplement-mar-28-1925-DW-LOC.pdf