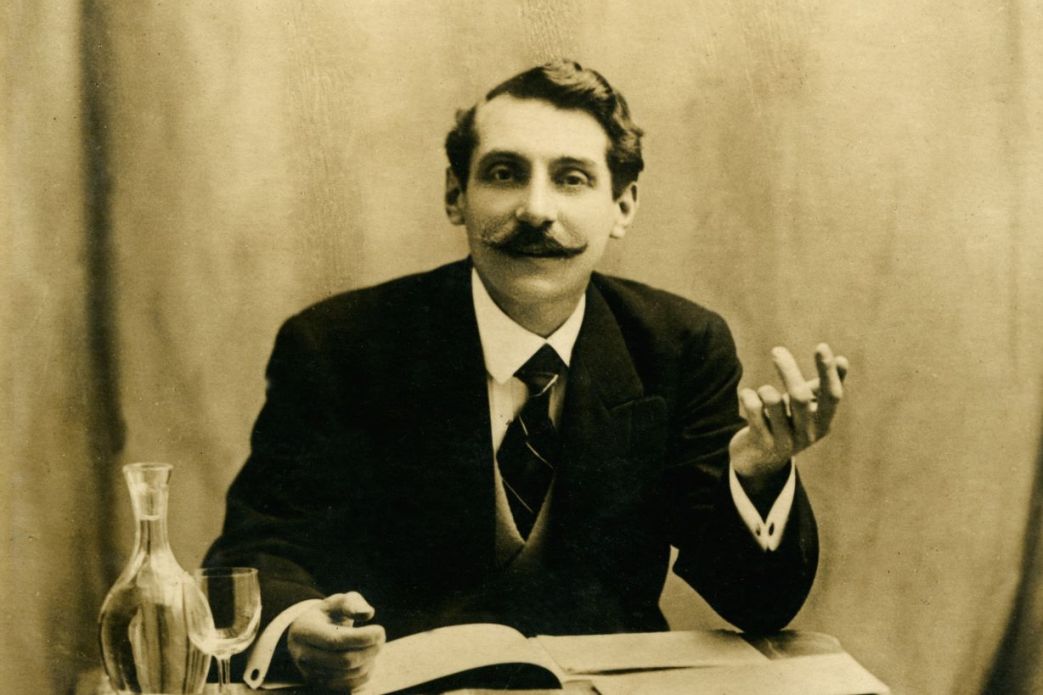

‘Economic Origins of the Belief of God in the Bourgeois’ (1906) by Paul Lafargue from Social and Philosophical Studies. Translated by Charles H. Kerr. Charles H. Kerr Publishing, Chicago. 1906.

It might reasonably have been hoped that the extraordinary development and popularization of scientific knowledge and the demonstration of the necessary linking of natural phenomena might have established the idea that the universe ruled by the law of necessity was re moved from the caprices of any human or superhuman will and that consequently God be came useless since he was stripped of the multiple functions which the ignorance of the savages had laid upon him; nevertheless it can not but be recognized that the belief in a God, who can at his will overthrow the necessary order of things, still persists in men of science, and that such a God is still in demand by the educated bourgeois, who asks him as the savages do for rain, victory, cures, etc.

Even if the scientists had succeeded in creating in bourgeois circles the conviction that the phenomena of the natural world obey the law of necessity in such sort that, determined by those which precede them, they determine those which follow them, it would still have to be proved that the phenomena of the social world are also subject to the law of necessity. But the economists, the philosophers, the moralists, the historians, the sociologists, and the politicians who study human societies, and who even assume to direct them, have not succeeded, and could not succeed in creating the conviction that social phenomena depend upon the law of necessity like natural phenomena; and it is because they have not been able to establish this conviction that the belief m God is a necessity for bourgeois brains, even the most cultivated ones. If philosophical determinism reigns in the natural sciences it is only because the Bourgeoisie has permitted its scientists to study freely the play of natural forces, which it has every motive to under stand, since it utilizes them in the production of its wealth; but by reason of the situation that it occupies in society it could not grant the same liberty to its economists, philosophers, moralists, historians, sociologists and politicians, and that is why they have not been able to introduce philosophical determinism into the sciences of the social world. The Catholic Church for a like reason formerly forbade the free study of nature, and its social dominance had to be overthrown in order to create the natural sciences.

The problem of the belief in God on the part the Bourgeoisie can not be approached without an exact notion of the role played by this class in society. The social role of the modern bourgeoisie is not to produce wealth, but it is to have it produced by wage workers, to seize upon it and distribute it among its members after having left to its manual and intellectual producers just enough for their nourishment and reproduction.

The wealth taken away from the laborers forms the booty of the bourgeois class. The barbarian warriors after the taking and sacking of a city put the products of the pillage into a common fund, divided them into parts as equal as possible and distributed them by lot among those who had risked their lives to conquer them.

The organization of society permits the bourgeoisie to seize upon wealth without any one of its members being forced to risk his life. The taking possession of this colossal booty without incurring dangers is one of the greatest marks of progress in our civilization. The wealth despoiled from the producers is not divided into equal parts to be distributed by lot; it is distributed under form of rents, incomes, dividends, interests, and industrial and commercial profits, proportionately to the value of the real or personal property; that is to say, to the extent of the capital possessed by each bourgeois.

The possession of a property, a capital, and not that of physical, intellectual or moral qualities is the indispensable condition for receiving a part in the distribution of the wealth. A child in swaddling clothes, as well as an adult, may have a right to its share of the wealth. A dead man possesses it so long as a living man has not yet perfected his title to his property. The distribution is not made among men, but among properties. Man is a zero; property alone counts.

A false analogy has been drawn between the Darwinian struggle which the animals wage among themselves for the means of subsistence and reproduction and that which is let loose among the bourgeois for the distribution of wealth. The qualities of strength, courage, agility, patience, ingenuity, etc., which assure victory to the animal, constitute integral parts of his organism, while the property which gives the bourgeois part of the wealth which he has not produced is not incorporated in his individuality. This property may increase or decrease and thus procure for him a larger or smaller share with out its increase or diminution being occasioned by the exercise of his physical or intellectual qualities. At the very most it might be said that trickery, intrigue, charlatanism, in a word, the lowest mental qualities permit the bourgeois to take a part larger than that which the value of his capital authorizes him to take; in that case he pilfers from his bourgeois brothers. If then the struggle for life can in a number of cases be a cause for progress among animals, the struggle for wealth is a cause of degeneracy for the bourgeois.

The social mission of grasping the wealth produced by the wage-workers makes of the bourgeoisie a parasitic class; its members do not contribute to the creation of wealth, with the exception of a few whose number is constantly diminishing, and the labor which they furnish does not correspond to the portion of wealth which falls to them.

If Christianity, after having been in the first centuries the religion of the mendicant crowds whom the state and the wealthy supported by daily distributions of food, has become that of the bourgeoisie the parasitic class par excellence, it is because parasitism is the essence of Christianity.

Jesus in his sermon on the mount explained its character in a masterly fashion; it is there that he formulates the Our Father, the prayer which every believer must address to God to ask him for his “daily bread” instead of asking him for work; and in order that no Christian worthy of the name may be tempted to resort to work for obtaining the necessaries of life, the Christ adds,

“Consider the birds of the air, they sow not neither do they reap, and your Heavenly Father feedeth them * * * take no thought therefore and do not say, to-morrow what shall we eat, or what shall we drink, or wherewithal shall we be clothed. * * * Your Heavenly Father knoweth that you have need of all these things.”

The Heavenly Father of the bourgeoisie is the class of manual and intellectual wage workers; this is the God who provides for all its needs.

But the bourgeoisie can not recognize its parasitic character without at the same time signing its death warrant; so while it leaves the bridle on the neck of its men of science, that without being troubled with any dogma nor stopped by any consideration they may give themselves up to the freest and most profound study of the forces of nature, which it applies to the production of its wealth, it forbids to its economists, philosophers, moralists, historians, sociologists, and politicians the impartial study of the social world, and condemns them to the search of reasons that may serve as excuses for its phenomenal fortune.1 Concerned only with the returns received or to be received, they are trying to find out, if by some lucky chance social wealth might not have other sources than the labor of the wage- worker, and they have discovered that the labor the economy, the method, the honesty, the knowledge, the intelligence, and many other virtues of the bourgeois manufacturers, merchants, landed proprietors, financiers, shareholders, and income- drawers, contributed to its production in a manner far more efficacious than the labor of the manual and intellectual wage-workers, and there fore they have the right to take the lion s share and to leave the others only the share of the beast of burden.

The bourgeois hears them with a smile, be cause they sing his praises, he even repeats these impudent assertions, and calls them eternal truths; but, however slender his intelligence, he can not admit these things in his inmost soul, for he has only to look around him to perceive that those who work their life through, if they do not possess capital, are poorer than Job, and that those who possess nothing but knowledge, intelligence, economy, honesty, and who exercise these qualities, must limit their ambition to their daily pittance, and rarely hope for anything beyond Then he says to himself: “If the economists, the philosophers, and the politicians with all their wit and literary training have not been able, in spite of their conscientious search, to find more valid reasons for explaining the wealth of the bourgeoisie, it is because there is something crooked in the business, some unknown cause whose mysteries are beyond us.” An Unknowable of the social order plants itself before the capitalist’s eyes.

The capitalist, for the sake of social peace, is interested that the wage-workers should believe his riches to be the fruit of his innumerable virtues, but in reality he cares as little to know that they are the rewards of his good qualities as to know that truffles, which he eats as voraciously as the pig, are vegetables capable of cultivation; only one thing matters to him, namely, to possess them, and what troubles him is to think that he may lose them without any fault of his own. He can not help having this unpleasant perspective, since even in the narrow circle of his acquaintance, he has seen certain persons lose their possessions, while others became rich after having been in distress. The causes of these reverses and strokes of fortune are beyond him as well as beyond the people who experienced them. In a word, he observes a continual going and coming of wealth, the causes of which are for him within the realm of the Unknowable, and he is reduced to setting down these changes of fortune to chance, to luck.2

It is too much to hope that the bourgeois should ever arrive at a positive notion of the phenomena of the distribution of wealth, since in proportion as mechanical production develops, property is depersonalized and takes on the collective and impersonal form of corporations with their stocks and bonds, the titles to which are finally dragged into the whirlpool of the stock exchange. There they pass from hand to hand without the buyers and sellers having seen the property which they represent, or even knowing exactly the geographical place where it is situated. They are exchanged, lost by some and won by others, in a manner which comes so near gambling that the distinction is difficult to draw. All modern economic development tends more and more to transform capitalist society into one vast international gambling house where the bourgeois win and lose capital, thanks to unknown events which escape all foresight, all calculation, and which seem to them to depend on nothing but chance. The Unknowable is enthroned in bourgeois society as in a gambling house.

Gambling, which on the stock exchange is seen without disguise, has always been one of the conditions of commerce and industry; their risks are so numerous and so unforeseen, that often the enterprises which are conceived, calculated and carried out most skillfully fail, while others undertaken lightly, in a happy-go-lucky fashion, succeed. These successes and failures, due to unexpected causes generally unknown and apparently arising only from chance, predispose the bourgeois to the mental attitude of the gamester; the game of the stock exchange fortifies and vivifies this mental cast. The capitalist whose fortune is invested in stocks sold on the exchange, who is ignorant of the reason for the variations of their prices and dividends, is a professional gamester. Now the gamester, who can account for his gains or losses only as a good run or a bad run, is an eminently superstitious individual; the frequenters of gambling houses all have magical charms to compel good fortune; one mumbles a prayer to St. Anthony of Padua, or no matter what spirit from Heaven, another plays only when a certain color has won, another holds a rabbit’s foot in his left hand, etc.

The Unknowable of the social order envelops the bourgeois as the Unknowable of the natural order surrounded the savage; all or nearly all the acts of civilized life tend to develop in him the superstitious and mystical habit of assigning everything to chance, like the professional gamester. Credit, for example, without which commerce and industry are impossible, is an act of faith in chance, in the unknown, performed by him who gives the credit, since he has no positive guarantee that the one who receives the credit will be able to meet his obligations at maturity his solvency depending upon a thousand and one accidents that can not be foreseen nor understood. Other economic phenomena instill every day into the bourgeois mind the belief in a mystical force without material support; detached from everything material. The bank note, to cite a single example, holds within itself a social force so far beyond its small material consequence that it prepares the bourgeois mind for the idea of a force, which should exist independently of matter. This miserable rag of paper, which no one would stoop to pick up, were it not for its magical power, gives its possessor all material things most to be desired in the civilized world; bread, meats, wine, house, lands, horses, women, health, consideration, honors, etc., the pleasures of the senses and the delights of the soul; God could do no more. Bourgeois life is woven out of mysticism.3

Commercial and industrial crises confront the terrified bourgeois, – uncontrollable, unchecked forces of a power so irresistible that they scatter disasters as terrible as the wrath of the Christian God. When they are unchained in the civilized world they ruin capitalists by thousands and destroy products and means of production by hundreds of millions. For a century the economists have recorded their periodical returns without being able to advance any plausible hypothesis of their origin. The impossibility of finding their causes on earth has suggested to certain English economists the idea of looking for them in the sun; its spots, they say, destroying by droughts the harvests of India, might diminish its capacity for purchasing European merchandise and might determine the crises. These grave sages carry us back scientifically to the judicial astrology of the middle ages, which subjected the events of human societies to the conjunction of the stars, and to the belief of savages in the action of shooting stars, comets, and eclipses of the moon upon their destinies.

The economic world swarms with fathomless mysteries for the bourgeois, mysteries which the economists resign themselves to leaving unexplored. The capitalist, who, thanks to his scientists, has succeeded in domesticating natural forces, is so amazed by the incomprehensible effects of economic forces that he declares them uncontrollable, like God, and he thinks that the wisest course is to endure patiently the ills which they inflict and accept gratefully the favors which they grant. He says with Job: “The Lord gave and the Lord hath taken away, blessed be the name of the Lord.” Economic forces appear to him in a fantasm as friendly and hostile spirits.4

The terrible and inexplicable phenomena of the social order which surround the capitalist and strike him without his knowing why or how in his industry, his commerce, his fortune, his well-being, his life, are as disquieting for him as were for the savage the terrible and inexplicable phenomena of nature which excited and overheated his exuberant imagination. Anthropologists account for the primitive man’s belief in witchcraft, in the soul, in spirits and in God, on the ground of his ignorance of the natural world the same explanation holds for the civilized man his spiritualist ideas and his belief in God should be attributed to his ignorance of the social world, the uncertain duration of his prosperity, and the inknowable causes of his fortunes and misfortunes, predispose the bourgeois to admit, like the savage, the existence of superior beings, which act on social phenomena as their fancies lead them whether favorably or unfavorably, as described by Theognis and the writers of the Old Testament. To propitiate them he practices the grossest superstition, communicates with spirits from the other world, burns candles before sacred images and prays to the trinitarian God of the Christians or the one God of the philosophers.

The savage, in daily contact with nature, is especially impressed by the unknown things of the natural order, which on the contrary worry the bourgeois but slightly; the only nature he knows about has been agreeably decorated, trimmed, graveled, raked off and generally domesticated. The numerous services that science has already rendered for his enrichment, and those he still expects from her, have engendered in his mind a blind faith in her power. He does not doubt but that some day she will solve the unknown problems of nature and even prolong indefinitely his own life, as promised by Metchnikoff, the microbe-maniac. But it is not so with the unknown things of the social world, the only ones that trouble him; these seem to him impossible of comprehension. It is the unknowable of the social world, not of the natural world, which insinuates into his unimaginative head the idea of God, an idea which he did not have the trouble of inventing, but found ready to be appropriated. The incomprehensible and insoluble social problems make God so necessary that he would have invented Him, had need been.

The bourgeois, vexed by the bewildering go and come of fortunes and misfortunes, and by the puzzling play of economic forces, is further more confused by the brutal contradiction of his own conduct and that of his fellows with the current notions of justice, morality, honesty; he repeats these sententiously, but refrains from regulating his acts by them, although he insists that they be observed strictly by the people who come into contact with him. For example, if the merchant hands his customer goods that are damaged or adulterated, he still wishes to be paid in sterling money; if a manufacturer cheats the laborer on the measurement of his work, he will not submit to losing a minute of the day for which he pays him; if the bourgeois patriot (all bourgeois are patriots) seizes the fatherland of a weaker nation his commercial dogma is still the integrity of his country, which according to Cecil Rhodes is a vast commercial establishment. Justice, morality and other principles more or less eternal, are valuable for the bourgeois, but only if they serve his interests; they have a double face, an indulgent and smiling one turned toward himself, and a frowning and commanding face turned toward others.

The constant and general contradiction between people’s acts and their notions of justice and morality, which might be thought of a nature to disturb the idea of a just God in the bourgeois mind, rather confirms it, and prepares the ground for that of the immortality of the soul, which had disappeared among nations that had reached the patriarchal period. This idea is preserved, strengthened and constantly revivified in the bourgeois by his habit of expecting a reward for everything he does or does not do.5 He employs laborers, manufactures goods, buys, sells, lends money, renders any service, whatever it be, only in the hope of being rewarded, of reaping a benefit. The constant expectation of profit results in his performing no act for the pleasure in it, but to pocket a recompense; if he is generous, charitable, honorable, or even if he limits himself to not being dishonest, the satisfaction of his conscience is not enough for him; a reward is essential if he is to be satisfied and not feel that he has been duped by his good and candid feelings; if he does not receive his reward on earth, which is generally the case, he counts on getting it in heaven. Not only does he expect a reward for his good acts, and his abstention from bad acts, but he hopes to receive compensation for his misfortunes, his failures, his vexations and even his annoyances. His ego is so aggressive that to satisfy it he annexes heaven to earth. The wrongs in civilization are so numerous and so crying, and those of which he is the victim assume in his eyes such boundless proportions, that his sense of eternal justice can not conceive but that some day they shall be redressed; and it is only in another world that this day can shine; only in heaven is he assured of receiving the reward for his misfortunes. Life after death becomes for him a certainty, for his good God, just and adorned with all bourgeois virtues, can not but grant him rewards for what he has done and has not done, and amends for what he has suffered; in the business tribunal of heaven, the accounts not adjusted on earth will be audited.

The bourgeois does not give the name of injustice to his monopolizing of the wealth created by wage-workers; for him this robbery is justice itself, and he can not conceive how any imaginable God could have a different opinion on the subject. Nevertheless, he regards it as no violation of eternal justice to allow the laborers to cherish the desire to improve their conditions of life and of labor; but as he is keenly aware that these improvements would have to be made at his expense, he thinks it good policy to promise them a future life, where they shall feast like bourgeois. The promise of posthumous happiness is for him the most economical way to satisfy the laborers demands. Life beyond the grave, at first a pleasure of hope for the satisfaction of his ego, becomes an instrument of exploitation.

Once it is settled that in heaven the accounts of earth are to be definitely settled, God necessarily becomes a judge having at his disposal an Eldorado for some and a prison for others, as is laid down by Christianity, following Plato.6 The celestial judge renders his decrees according to the judicial code of civilization, enriched by a few moral laws which can not figure in it, owing to the impossibility of establishing the offense and finding the proof.

The modern bourgeois occupies himself mainly with the rewards and compensations beyond the tomb; he takes but a moderate interest in the punishment of the wicked, that is to say, the people who have injured him personally. The Christian hell disturbs him little; first, because he is convinced that he has done nothing and can do nothing to deserve it, and second, because his resentment against his fellows who have sinned against him is but short-lived. He is always disposed to renew his relations of business or pleasure with them if he sees any advantage in it; he even has a certain esteem for those who have duped him, since after all they have done to him only what he has done or would have liked to do to them. Every day in bourgeois society we see persons whose pilferings had made a scandal, and who might have been thought forever lost, return to the surface and achieve an honorable position; nothing but money was demanded of them as a condition for resuming business and making honorable profits.7

Hell could only have been invented by men and for men tortured by the hate and the passion of vengeance. The God of the first Christians is a pitiless executioner, who takes a savory pleasure in feasting his eyes on the tortures inflicted for all eternity on the infidels, his enemies.

“The Lord Jesus,” says St. Paul, “shall ascend into heaven with the angels of his power, with burning flames of fire, working vengeance against those who know not God and who obey not the Gospel; they shall be punished with an everlasting punishment before the face of God and before the glory of his power.” – II. Thess. I, 6–9.

The Christian of those days expected with an equally fervent faith for the reward of his piety and the punishment of his enemies, who became the enemies of God. The bourgeois, no longer cherishing these fierce hates (hate brings no profits), no longer needs a hell to assuage his vengeance, nor an executioner-God to chastise his associates who have clashed with him.

The belief of the bourgeoisie in God and in the immortality of the soul is one of the ideological phenomena of its social environment; it will never lose it till it is dispossessed of its wealth stolen from wage-workers, and transformed from a parasitic class into a productive class.

The bourgeoisie of the eighteenth century, which struggled in France to grasp the social dictatorship, attacked furiously the Catholic clergy and Christianity, because they were props of the aristocracy; if in the ardor of battle some of its chiefs, Diderot, La Mettrie, Helvetius, d’Holbach, pushed their irreligion to the point of atheism, others, quite as representative of its spirit, if not more so, Voltaire, Rousseau, Turgot, never arrived at the negation of God. The materialist and sensualist philosophers, Cabanis, Maine de Biran, de Gerando, who survived the Revolution, publicly retracted their infidel doctrines. We must not waste our time in accusing these remarkable men of having betrayed the philosophical opinions which, at the opening of their career, had assured them fame and livelihood; the bourgeoisie alone is guilty. Victorious, it lost its irreligious combativeness, and like the dog in the Bible, it returned to its vomit. These philosophers underwent the influence of the social environment; being bourgeois, they evolved with their class.

This social environment, from the workings of which not even the most learned nor the most emancipated of the bourgeois can free themselves, is responsible for the deism of men of genius, like Cuvier, Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Faraday, Darwin, and for the agnosticism and positivism of contemporary scientists, who, not daring to deny God, abstain from concerning themselves with him. But this very act is an implicit recognition of the existence of God, whom they need in order to understand the social world, which seems to them the plaything of chance, rather than ruled by the law of necessity, like the natural world.

M. Brunetiere, thinking to dart an epigram at the free-thought of his class, quotes the phrase of the German Jesuit Gruber, that “the Unknowable is an idea of God appropriate to Free Masonry.” The Unknowable can not be any one s idea of God; but it is its generating cause, in savages and barbarians as well as in Christian bourgeois or Free Masons. If the unknown elements of the natural environment made necessary for the savage and barbarian the idea of a God, creator and ruler of the world, the unknown elements of the social environment make necessary for the bourgeois the idea of a God who shall distribute the wealth stolen from the manual and intellectual wage-workers, dispense blessings and curses, reward good deeds, avenge injuries and repair wrongs. The savage and the bourgeois are drawn unsuspectingly into the belief in God, just as they are carried along by the rotation of the earth.

NOTES

1. The history of political economy is instructive. At a time when capitalist production, In the first stage of its evolution, had not yet transformed the mass of the bourgeois into parasites, the Physiocrats, Adam Smith, Ricardo, etc., could make an impartial study of economic phenomena, and search out the general laws of production. But since the machine-tool and steam require the co-operative efforts of wage-workers alone in the creation of wealth, the economists confine themselves to the collection of facts and statistical figures, valuable for the speculations of commerce and the Stock Exchange, without endeavoring to group and classify them, so as to draw theoretical conclusions, since these could only be dangerous to the dominance of the possessing class. Instead of building up science, they are fighting socialism; they have even wished to refute the Ricardian theory of value because socialist criticism had taken possession of it.

2. The capitalist mind has in all ages been tormented by th constant uncertainty of fortune, represented in Greek Mythology by a winged woman standing upon a wheel with her eyes bandaged. Theognis, the Megarian poet of the fifth century before the Christian era, whose poetry, according to Isocrates, was a text book In the Greek schools, said:

“No man is the cause of his gains and of his losses, the Gods are the distributors of wealth. * * * * We human beings cherish vain thoughts, but we know nothing. The Gods make all things come about according to their own will. * * Jupiter inclines the balance sometimes to one side and some times to the other, according to his will, that one may be rich, and then at another time may possess nothing. * * No man is rich or poor, noble or commoner, without the intervention of the Gods.”

The authors of Ecclesiastes, Psalms, Proverbs and Job make Jehovah play the same part. The Greek poet and the Jewish writers express the capitalists’ thought.

Megara, like Corinth, its rival, was one of the first maritime cities of ancient Greece in which commerce and industry developed. A numerous class of artisans and capitalists took shape there and stirred up civil wars in its struggle for political power. About sixty years before the birth of Theognis, the democrats, after a victorious revolt, abolished the debts due to the aristocrats and required the restitution of the Interest which had been extorted. Theognis, although a member of the aristocratic class and although he cherished a ferocious hatred against the democrats, whose black blood as he said he would gladly have drunk, because they had robbed and banished him, could not escape the influence of the bourgeois social environment. He is impregnated with its ideas and sentiments, and even with its language: thus on several occasions he draws metaphors from the assaying of gold, to which the merchants were constantly obliged to resort that they might know the value of the coins and ingots given them in exchange. It is precisely because the gnomic poetry of Theognis, like the books of the Old Testament, carried the maxims of bourgeois wisdom, that it was a school book In democratic Athens. It was, said Xenophon, a treatise on man such as a skillful horseman might write on the art of riding.

3. Renan, whose cultivated mind was clouded with mysticism, had decided that sympathy for the impersonal form of property. He relates in his Memories of Childhood (VI) that instead of devoting his gains to the acquirement of real estate he preferred buying “stocks and bonds which are lighter, more fragile, more ethereal.” The bank note is a value quite as ethereal as stocks and bonds.

4. Crises impress the bourgeois so vividly that they talk of them as if they were corporeal beings. The celebrated American humorist Artemus Ward relates that hearing certain financiers and manufacturers in New York affirm so positively: “The crisis has come, it is here,” he thought it must be in the room, and to see what kind of head it had, he began looking for it under the tables and chairs.

5. Theognis, like Job and other Old Testament authors is embarrassed by the difficulty of reconciling the injustice of men with the justice of God.

“O Son of Saturn,” says the Greek poet, “how canst thou grant the same lot to the just and to the unjust? * * * O king of the immortals, is it just that he who has committed no shameful act, has not transgressed the law, who has sworn no false oaths, but who has always remained honorable, should suffer? * * * The unjust man, full of himself, who fears the wroth neither of men nor of gods, who commits deeds of injustice, is gorged with riches, while the just man shall be despoiled and shall be consumed by hard poverty. * * What mortal is he that, seeing these things, fears the gods?”

The Psalmist says:

“Behold, these are the ungodly, who prosper in the world; they increase in riches * * * When I thought to know this, It was too painful for me. * * * I was envious of the foolish (those who fear not the Eternal) when I saw the prosperity of the wicked.” (Psalm LXXIII.)

Theognis and the Jews of the Old Testament, not believing In the existence of the soul after death, think that it is on earth that the wicked Is punished, “for higher is the wisdom of the gods,” says the Greek moralist.

“But that vexes the spirit of men, since it is not when the act is committed that the immortals wreak vengeance for the fault. One pays the debt in his own person, another condemns his children to misfortune.”

Men are punished for Adam’s sin, according to Christianity.

6. Socrates, in the tenth and last book of the Republic, cites as worthy of belief the story of an Armenian who, left for dead ten days on the battlefield, came to life again, like Jesus, and related that he had seen in the other world “souls punished ten times for each unjust act committed on earth.” They were tortured by “hideous men, who appeared all on fire. * * They flayed the criminals dragged them over thorns, etc.” The Christians, who drew part of their moral ideas from the Platonic sophistry, had but to complete and improve Socrates story to establish their hell, adorned with such frightful horrors.

7. Emile Peréire, the day after the scandalous crash of the Credit Mobilier, of which he was the founder and manager, meeting on the boulevards a friend who made as though he would not recognize him, went straight to him and said loudly; “You can salute me, I have several millions yet” The challenge, interpreting so well the bourgeois feeling, received due comment and appreciation. Peréire died a hundred times a millionaire, honored and regretted.

Social and Philosophical Studies by Paul Lafargue. Translated by Charles H. Kerr. Charles H. Kerr Publishing, Chicago. 1906.

The Charles H Kerr publishing house was responsible for some of the earliest translations and editions of Marx, Engels, and other leaders of the socialist movement in the United States. Publisher of the Socialist Party aligned International Socialist Review, the Charles H Kerr Co. was an exponent of the Party’s left wing and the most important left publisher of the pre-Communist US workers movement.

PDF of Book:https://archive.org/download/socialphilosophi00lafa/socialphilosophi00lafa.pdf