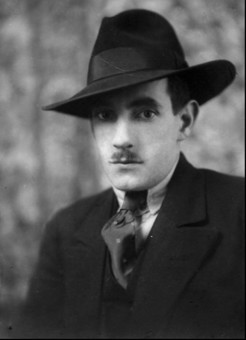

Written shortly before his return to Ireland, Newry-born Eadmonn MacAlpine on the emergence of Sinn Fein as the revolutionary force in Ireland, placing it in context of Irish history. MacAlpine had emigrated to the U.S. in 1915 where he became deeply involved in the Socialist Party’s left wing, was a founder of both the Communist Labor Party and Ireland’s first Communist Party. With James Connolly’s son Roddy, MacAlpine would be Irish delegate to the 2nd Comintern Congress.

‘Sinn Fein–and the New Struggle’ by Eadmonn MacAlpine from Revolutionary Age. Vol. 1 No. 4. November 27, 1918.

PRACTICALLY every generation of Irishmen during the past 700 years has witnessed an armed uprising against English domination. Indeed during the first 500 years of the English occupation the country was in a continuous state of war–sometimes the Irish gained the ascendency and other times the tide of battle favored the invader. On the whole, although the English did succeed in finally establishing themselves on a firm basis the Irish remained an unbeaten people in the sense that a certain section of the population steadfastly refused to acknowledge the conquest. This section was not confined to any particular part of the island, but arose here and there as opportunity presented itself.

Since the passing of the act of union in 1800 the form of resistance changed from that of a people continually at war with an alien invader to that of outbursts of rebellion against an established authority–but always lay the undercurrent of the section which asserted Ireland’s nation- hood and their determination to sweep the foreign domination out of the land for all time.

It is important that these two forces be borne in mind that which refused to recognize England’s authority at any and all times and that which recognized the union but rose in revolt against intolerable conditions. The latter section were the people who made the risings possible while the former were composed chiefly of a few middle class idealists. Irish history in dealing with these revolts, or risings, pays nearly all its attention to the idealists and the more Irish the history the more it misrepresents this point.

The people who formed the bulk of the fighters in all these revolts were of the same class as those who fight in all revolutions the dispossessed. From the period of 1740 until the signing of the act of union the peasants–the agricultural section, and in the Ireland of that period the majority, of the working class–were in continual revolt under the various names of Whiteboys, Oakboys and Steelboys. In all cases the revolts had their origins in the oppressive conditions governing the lives of the peasantry. Thousands of these peasants were hung or jailed for life and at different times pitched battles took place between them and the soldiery, yet conventional Irish history gives them only a passing mention, and so it is throughout the pages of Ireland’s story. The patriotic side is stressed and the economic–the important side–is left practically untouched.

James Connolly, whose martyr death is being misrepresented by the Irish bourgeoisie today, says of these same forces in his work “Labour in Irish History”:

“Hence the spokesmen of the middle class, in the press and on the platform, have consistently sought the emasculation of the Irish National movement, the distortion of Irish history, and, above all, the denial of all relation between the social rights of the Irish toilers and the political rights of the Irish nation. It was hoped and intended by this means to create what is termed ‘a real National movement’–i.e., a movement in which each class would recognize the rights of the other classes and laying aside their contentions would unite in a national struggle against the common enemy–England. Needless to say, the only class deceived by such phrases was the work- ing class. When questions of ‘class’ interests are eliminated from public controversy a victory is thereby gained for the possessing, conservative class, whose only hope of security lies in such elimination. Like a fraudulent trustee, the bourgeois dreads nothing so much as an impartial and rigid inquiry into the validity of his title deeds. Hence the bourgeois press and politicians incessantly strive to inflame the working class mind to fever heat upon questions outside the range of their own class interests. War, religion, race, language, political reform, patriotism–apart from whatever intrinsic merits they may possess–all serve in the hands of the possessing class as counter-irritants, whose function it is to avert the catastrophe of social revolution by engendering heat in such parts of the body politic as are farthest removed from the seat of economic enquiry, and consequently of class consciousness on the part of the proletariat.”

From this brief outline it can be seen that due to their ignorance of their own real history, due to the fact that all, or practically all, Irish prose, poetry and song is heavy with the story of unequal fights, disastrous defeats and the ensuing reigns of Terror, and due to the living reality of capitalistic misrule in Ireland, the Irish working class easily falls a victim to the charlatans who lay all its misery to English rule and keeps its eyes from the economic situation at home.

The Irish Parliamentary party have long played this game, ably aided whether consciously or not by the Unionist party of Ulster, and between them they succeeded in keeping the Irish worker’s eyes fixed on London and his hopes centered on the coming of Home Rule. The Ulster unionists play their part by keeping the Ulster workman terrorized with the prospect of Home Rule and directing his energies to combating this imaginary evil lest he should find an outlet for them nearer home.

But of recent years the Irish parliamentary party has lost prestige. They talked revolt and revolution for a quarter of a century without ever coming near to action, they spoke continually of the dawn of Irish freedom and squabbled among themselves about petty reforms, they were loud in fulsome praise of “the Irish virtues” and became more and more copies of the English upper bourgeoisie, they damned the acts of England in reference to Ireland and supported her oppressions of other peoples. They continued in power largely by the prestige accruing from Parnell’s name and the support of the older generation who like themselves mistook talk for action, but the young er generation wanted action, they dreamed that Ireland might be free…

It was while Ireland was in this political “slough of despond” that the Sinn Fein policy was propagated. A pamphlet entitled “The Resurrection of Hungary–A Parallel for Ireland,” written by Arthur Griffiths was the herald of the new movement. The idea took root in the minds of the young men and within the next few years the movement grew to such proportions that a convention was held in Dublin in the latter part of 1905. It might be properly said that the Sinn Fein, or as it was sometimes called the Hungarian, policy was definitely launched in 1905. The break down of the Irish Parliamentary Party in 1906 and in 1909 gave the new movement an impetus and in a short time it had grown to such popularity that a daily paper was issued under the name Sinn Fein.

The chief reason for the growth of Sinn Fein may be fairly enumerated under two heads–the failure of the Irish Parliamentary Party to achieve Home Rule although it had obtained, what it Home Rule although it had obtained, what it always claimed as the one necessity to final success, the balance of power in the English House of Commons; and the fact that Sinn Fein had definite program of action.

Sinn Fein, in the narrower sense of the words, means “ourselves alone” or “by our own efforts,” but Jim Larkin, the Irish labor leader, writing in “The Masses” a short time after the Rebellion of 1916 gives to the movement a wider interpretation at the same time disavowing his belief in its economic doctrines. Nitsche has spoken of “the ascending will of the people;” he says, “such a term would be a more literal translation; and yet though all Socialists and radicals could appreciate the soul and meaning of such terms, it is necessary to explain right here that though the Sinn Fein movement from the intellectual side was approved of by the Irish revolutionary section of the working class, its economic basis as interpreted by the political section of that movement, by writers such as Arthur Griffiths, Bulmer Hobson and others, was strongly assailed. It should be understood that Griffiths and his narrow school of political propagandists imported the political and economic side of Sinn Fein from Hungary, a bastardized translation of Liszt’s economic philosophy. The Irish revolutionary movement, which comprised at least four-fifths of the men under arms in the late rebellion, never at any time identified itself with the Sinn Fein position. On the contrary, we at all times exposed their ignorance of economics, and their lack of knowledge of the interdependence of nation with nation, but were at one with them in their idea of building up a self-reliant nation.”

It was in the narrow sense of “ourselves alone” that the words Sinn Fein were first used. One of the chief planks in the platform was the withdrawal of the Irish representatives from the British Parliament and the establishment of a national council to which Irishmen should render voluntary obedience, ignoring as far as possible England’s existence in Ireland. This looked to young Ireland like action and the movement gained many adherents. Sinn Feiners were, however, insistent on the fact that they were not advocating physical resistance but were rather opposed to the physical force idea, urging passive resistance as the means to accomplish the desired end. Their desired end was not in itself very revolutionary–they advocated the rule of Ireland by a King, Lords and Commons, even going so far as to suggest that if the King of England would accept the Irish throne they would be satisfied; in other words they wanted a dual monarchy after the style of Austria-Hungary.

About the time that Sinn Fein came prominently before the public, the Irish Socialist and Labor movement showed signs of activity, in fact the Irish Labor movement might be said to have had its birth at this time. It was with the return of Larkin to Ireland that the Labor movement became a factor in the life of the country. It is true that labor unions existed in several large cities for a considerable time prior to 1907 but they were nearly all lifeless, or at least paralyzed, limbs of the British movement.

As a result of the lax manner in which he found the Irish branches of the English unions administered Larkin organized the Irish Transport and General Workers Union and from the moment of its inception it became a vital and revivifying influence in the life of the working class of the country.

Consequent upon the activity of the labor movement the real measure of the Sinn Fein, and parliamentary movements became apparent and then began the struggle between the two ideas; the old and the new–the conception of Irish liberty as a petty bourgeois freedom resultant from the creation of a semi-independent political state and the conception of liberty as an industrial democracy resultant from the establishment of a proletarian industrial republic, the rise to power of a class conscious proletariat and the consequent breaking of the shackles of both political and economic slavery. The class struggle–clear cut and definite–entered the field throwing the real issue into bold relief, unclouded by the bourgeois patriotism that had so long cast its baleful shadow on the life of the Irish working class. In this struggle, which developed into open warfare in the Dublin strike of 1912-13, the forces lined up in their historic order–the Irish and English bourgeoisie and capitalists on one side and the Irish working class, supported by their English, Welsh and Scotch brethren, on the other.

The Revolutionary Age (not to be confused with the 1930s Lovestone group paper of the same name) was a weekly first for the Socialist Party’s Boston Local begun in November, 1918. Under the editorship of early US Communist Louis C. Fraina, and writers like Scott Nearing and John Reed, the paper became the national organ of the SP’s Left Wing Section, embracing the Bolshevik Revolution and a new International. In June 1919, the paper moved to New York City and became the most important publication of the developing communist movement. In August, 1919, it changed its name to ‘The Communist’ (one of a dozen or more so-named papers at the time) as a paper of the newly formed Communist Party of America and ran until 1921.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/revolutionaryage/v1n04-nov-27-1918.pdf