It is hard not to read some bitterness into former political prisoner Harrison George’s account of the repression faced by the left in World War One, and the almost universal confusion he found in its ranks, including in prison.

‘Wartime Persecutions and Their Results’ by Harrison George from the Daily Worker Saturday Supplement. Vol. 2 No. 110. July 26, 1924.

The first Tuesday after the first Monday in the month of November, 1916, I stood in a snowdrift in the streets of Virginia, Minn., watching the bulletins of the election returns. Two of the I.W.W. leaders then most famous, Gurley Flynn and Joe Ettor, tended to favor Woodrow Wilson because he had “kept us out of war.” The syndicalist suspicion I held against all politicians did not fully account for my foreboding that Mr. Wilson would not continue his pacific role. He was elected on that supposition, however. But hardly before that snowdrift had melted, Woodrow Wilson had indorsed Morgan’s loan to the allies in the blood of American workers.

Everyone is “against war.” Every war minister of every capitalist government on earth will assure you he is against war. Even while he is signing mobilization orders to throw millions of workers into battle and death, he will emphatically assure you he is against war. But only simpletons believe that capitalist politicians, who are necessarily the tools of imperialism, are not hypocrites–are not willing and waiting to send armies of workers to slaughter in the interest of profiteering exploiters.

Gompers, too, is against war. says so. But when he says so he lies. In 1917 he did not even wait for the war declaration. He helped to rouse sentiment in favor of that declaration before it was issued. Gompers called a special convention of the A.F. of L. at Buffalo in February, 1917, to pledge class collaboration in the oncoming war.

Woodrow Wilson addressed this for convention, thanking Gompers “loyalty” and threatening any labor element that “kicked over the traces” with being “put in a corral.”

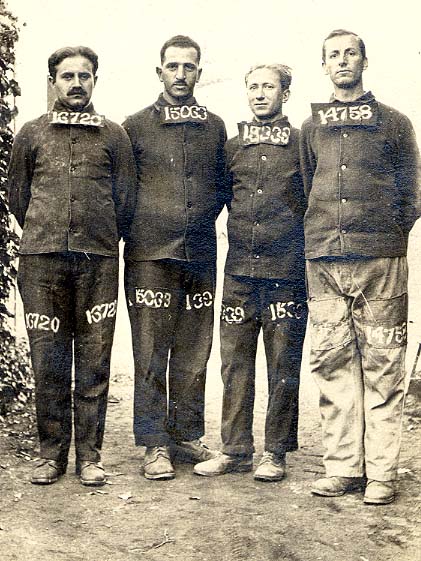

Those Who Were “Put in a Corral.”

This is a story of those who were put in a corral. It is not a case record of war persecutions. It aims rather to give a survey of those proletarian elements and organizations which suffered persecution in the war, and how they emerged from the struggle.

Neither shall I dwell upon the real persecution suffered by the petty bourgeois pacifist elements. Whatever their extent and degree, they count for nothing in the class struggle. They were individualists and remained individualists, objectors upon grounds of conscience not of class. If imperialism could exploit the proletariat bloodlessly, if capitalism could get its pound of flesh without one drop of blood–then the petty bourgeois pacifists would have no quarrel with capitalism.

Inherently, in the last war crisis, they cared only for their “souls.” They quibbled over legal loopholes–if they should refuse to fight before or after mobilization, if they would or would not accept non-combatant service with the war machine. While all the Babbitts regarded these sweet souls as dangerous, nothing could be sillier. They were only a nuisance, not a menace, to capitalist wars. They did not divert the war machine for one moment. They will never stop any war. Moreover, until they cease their subjective attitude, and carry even their weak anti-war propaganda vigorously into the ranks of the soldiers and sailors who are to do the fighting, all their protests against war as an institution will be justly branded as insincere.

Little Glory for Any One.

However, even those who opposed the war not from a personal, but from proletarian or supposed proletarian reasons, have nothing in an organizational sense of which to be proud. Unless, of course, one insists that it is the main purpose of revolutionists heroically to be dragged off to prison and gloriously to rot therein for a term of years.

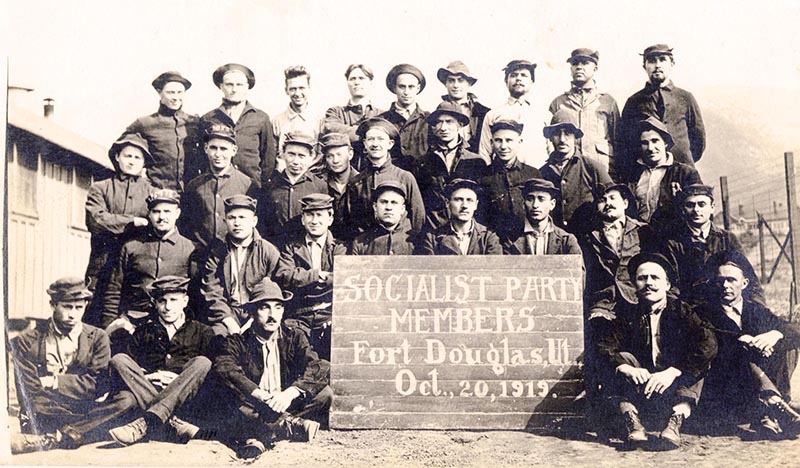

In this accomplishment all groups, even the socialist party, had to yield first place to the I.W.W. Only by the sentimental element was the St. Louis resolution of the S.P. against. war taken seriously. Everybody knew that Berger’s opposition to the war was not proletarian, but German-nationalistic, disguised with a pacifist veneer. Oscar Ameringer went from St. Louis back to Oklahoma and joined the terrorizing council of defense to help persecute the naive socialist farmers of Oklahoma who took the St. Louis resolution to mean something, and who took to the hills with their Winchester rifles prepared to resist conscription.

The Rise and Fall of the North Texas Republic.

I met some of these Oklahoma farmers in Leavenworth prison, together with those Texas farmers who, to show the world their resentment against the unconstitutional behavior of the conscriptionists, seceded from the United States and set up the Republic of North Texas. I believe the whole cabinet of the North Texas Republic was at Leavenworth, altho I recall meeting only its secretary of war. He was then tending the flock of prison poultry. I believe his name was Bryant–a fine type of fighting farmer, and I recall two things concerning him. He was continually and visibly engaged in chewing tobacco, and he was patently disillusioned with the socialist party. The obscure rank and file were too unimportant for the fine gentlemen at the head of the S.P. to defend from persecution.

The “League for Democratic Control” Gets Controlled.

At Leavenworth I met, also, the left wing socialist group led by Comrade Earl Browder and his brothers. These were, perhaps, the most sophisticated prisoners of the war. They had few illusions. By organizing the ephemeral League for Democratic Control to “test the constitutionality of the draft act” it was hoped to disillusion others. Some of these others shared both the disillusion and prison with the Browders, but did not come out as they did to resume the fight.

The most revolutionary plank of any anti-war program I know of was written into the demands of this organization, i.e., that the armed forces should be under the control of rank-and-file committees. No wonder Comrade Browder and I met at Leavenworth! But tho I waited there for five years, Berger never arrived. When he purchased immunity in 1919 by throwing out the left wing, I wrote Jim Reed–then at the first Communist convention–that Leavenworth was only for honest rebels anyhow.

In speaking of these rank-and-file committees in the army, we must not forget the two “strikes,” or rather mutinies, of the military prisoners at the disciplinary barracks at Fort Leavenworth. The first one was quite a success, led by an “intellectual objector,” Hi Simon. The second was ruthlessly crushed according to grapevine from “the barracks” to “our” civil prison–with deliberate murders of mutineers in their cells.

Vegetarianism in the Class War.

The symbol that best represents the decline of the socialist party from war persecution is the change in Debs. Debs, who had threatened to lead an army of workers to rescue Haywood Moyer and Pettibone from an Idaho hangman, who had counseled miners to buy rifles and machine guns, became, by passing thru the war persecution, the typical petty bourgeois pacifist, preaching Christly sweetness and non-resistance–a staunch upholder of vegetarianism in the class war.

In prison I have seen strong men weep like children, those thought most courageous to turn into arrant cowards–rationalizing their cowardice with polemics as to tactics, men respected and still respected by thousands treating an imprisoned comrade no better than a prison guard would have done just to curry favor with officials and receive some slight benefit. So I am not surprised to see what, by comparison, is a comparatively innocent change in Debs, from a sentimental fighter for his class to an all too saintly petty bourgeois pacifist. But it is a change, a shameful change. It represents the change in the S.P. Its small proletarian tendency was destroyed, and even its best elements were so at sea that in 1918 they were innocently talking a class collaboration program of “reconstruction”–in- stead of revolution.

The I.W.W.–an Example of Syndicalist Confusion.

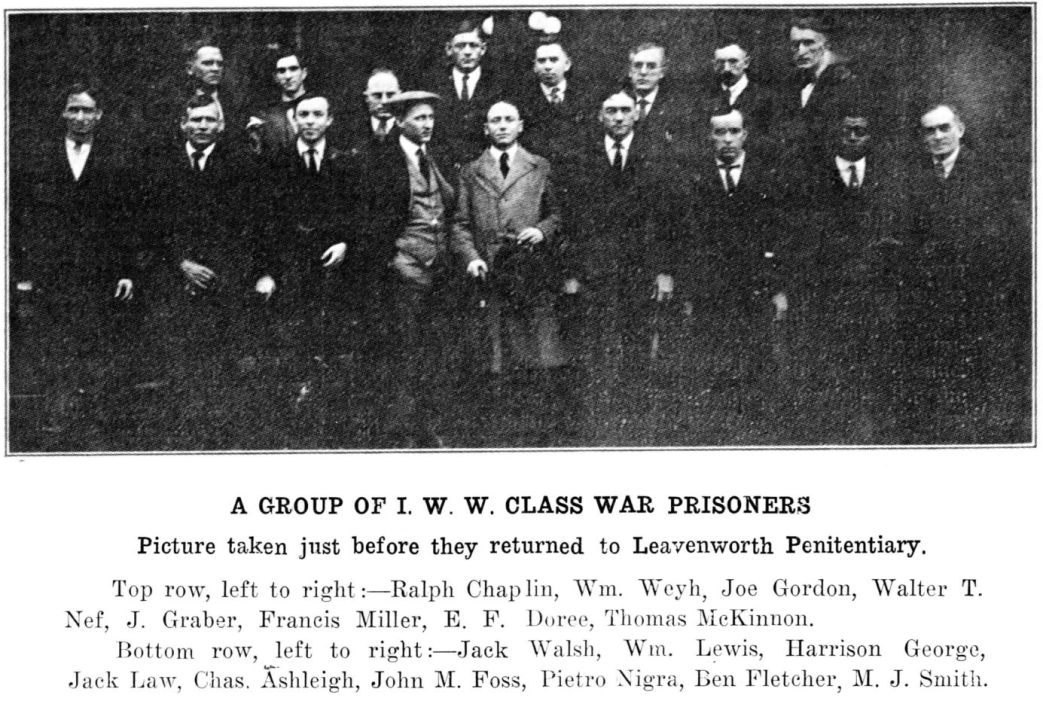

Some will say that the I.W.W., surely, has a record under war persecution that is beyond all criticism. If we speak of the fine type of fighting workers who made up the revolutionary minority (unorganized) both inside and outside of prison during the war, I agree. But as one of those who shared intimately in the catastrophic results of official confusion, I must add that, as an organization, the reputation of the I.W.W. for opposition to war, or for any consistent program in relation thereto, is unjustified.

The I.W.W., which has always tried to fulfill the contradictory functions of a revolutionary (tho anti-parliamentary) political party, and–at the same time–of a labor union, was taken in all its confusion by the war crisis. In spite of its advertised and many of its real virtues, it naturally suffered great mutilation under war persecution. Its failure to maintain its ideological unity and tone, and increase rather than decrease its power in the struggle, is a failure of the syndicalist argument that an economic organization can discharge the functions of a political party in leading the struggle.

Some leaders of the I.W.W. have learned this lesson from the war crisis, but–most remarkably–they do not go on from the acknowledgement that the union cannot be a political party to the logical conclusion that there should be a separate revolutionary political party organized. Far from it. They only disavow the political function–the struggle for power–altogether! They become pure and simple unionists! Industrial unionists, of course, but minus any program for the revolutionary overthrowal of capitalism–and many of them have become advocates of pacifism in the class struggle.

The G.E.B. met, quarreled, but could not agree on any statement. So none was made. Chaplin, then editor of Solidarity, waited until nearly registration day, then, disgusted, published his own statement, advising the I.W.W. members to register, but to claim exemption as “opposed to war.” This farcical situation was heightened when a defiant statement, upon which the G.E.B. could not agree, was found among papers taken in the raids and was used against us by Judge Landis with telling effect.

While the G.E.B. quarreled, the membership became confused. There was not even bad leadership. While Solidarity snorted defiance to the war lords, regiments of drafted I.W.W. were entrained, the Marine Transport Workers’ union was given trusted work and good wages in handling war supplies. It bought Liberty bonds and put up a service flag. All these excellencies were duly lugged into court to prove we were good patriots. But we were convicted just the same. Only the trial again proved, by a division among the defendants on how it should be conducted, that the revolutionary and the unionist elements were wholly at variance.

At Leavenworth the group was given over to numberless quarrels and recriminations. In spite of the fact that every issue could be seen looming up for future decision, no program was discussed or adopted concerning the group attitude toward parole, commutation or conditional release, until after the crisis was upon us and the group already irrevocably split. This fight became murderously bitter and, pushed into the foreground as an excuse for factionalism, is now ruining the organization outside. Gunplay and fights go on between leaders in headquarters who advocate pacifism to the masses in the class struggle. Both sides are equally certain that the I.W.W. needs no revolutionary minority organization such as the T.U.E.L. forms in the A. F. of L., and both are equally wrong.

Lately the leading speakers of the I.W.W. are acknowledging that it has no revolutionary mission, that it organizes for two things only–first, for the “everyday struggle,” second, to “carry on production after capitalism shall have been overthrown” (by the Communists, presumably!). The Workers Party invites those members of the I.W.W. who want to fill this hiatus and help to overthrow capitalism to join the Communist movement–without leaving the I.W.W., however. In the next war to end war the Communist Party will have work for these good fighters. In the next war, together with all the resentful elements from the last one dragged again into the ranks, will go the Communists, organized to carry on systematic work to turn the war into revolution. In the next war, if the revolutionists are persecuted, they can feel that they were persecuted for something.

The Saturday Supplement, later changed to a Sunday Supplement, of the Daily Worker was a place for longer articles with debate, international focus, literature, and documents presented. The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1924/v02a-n110-supplement-jul-26-1924-DW-LOC.pdf