The wars in the Balkans of the 1910s were not just the precursor to World War One, but foundational for the region’s modern states. Prolific Marxist historian Mikhail Pavlovitch, in 1913 living in Parisian exile, with an analysis.

‘Prospects of the Balkan War’ by Mikhail Pavlovitch from New Review. Vol. 1 No. 11. March 15, 1913.

Though there has been much pretended sympathy among the Russians for their Slav brothers in the Balkan-Turkish war, Russia has done little to help the Balkan States when called upon for real financial assistance. The wind of Russia’s favor has changed in the last ten years. Bulgaria, once the cherished daughter of Russia’s heart, is now treated like a step-daughter, and Russia’s official sympathy is more or less avowedly with Servia.

Patriotic Russian papers have been treating the Bulgars with more and more contempt of late, calling them and their press chauvinist and ultra-nationalist. The Bulgars, not to be outdone in a battle of words, have answered back. This has given both Russian and foreign papers a chance to say there is in Bulgaria a current of Russophobia which may prove a very serious affair.

All the feeling which Russia had for the Balkan peoples in their conflict must be explained by other than brotherly ties.

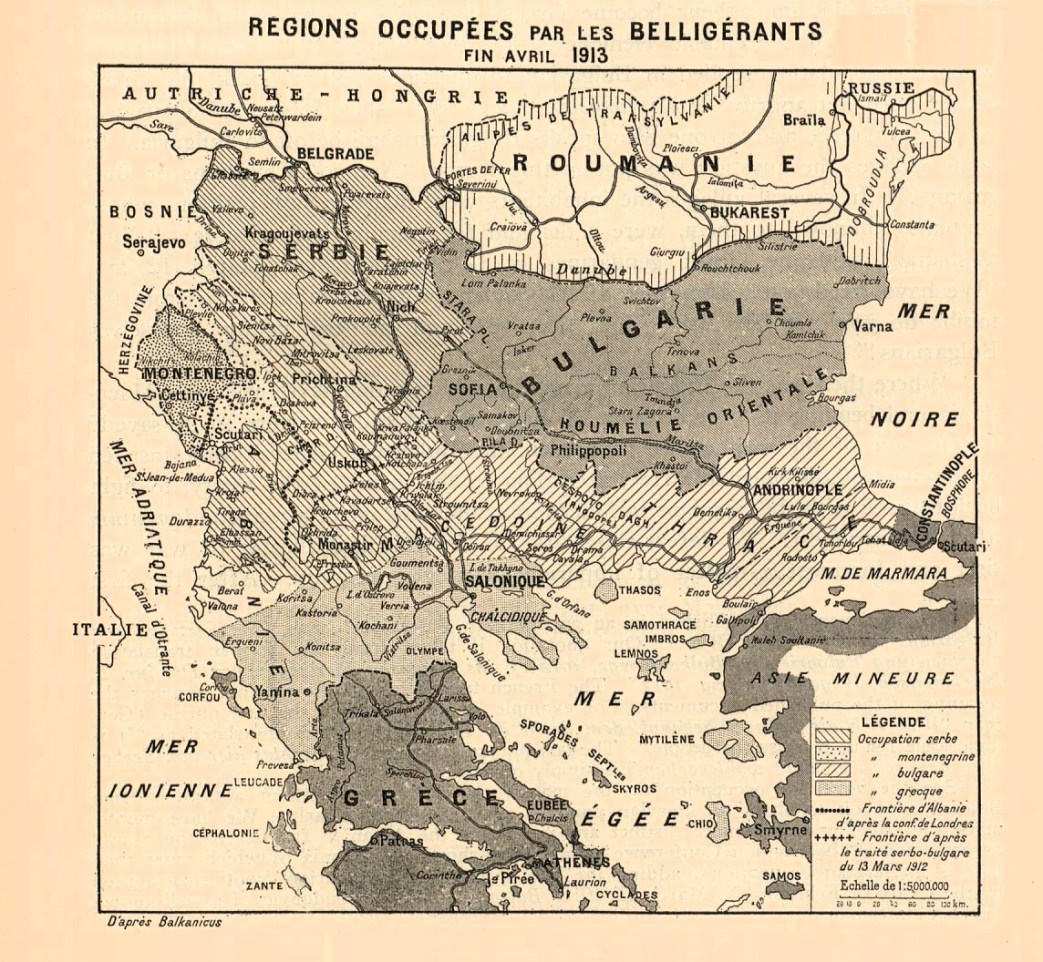

The federation of the Balkan States was hailed by Russian imperialists for two reasons: first, in the new and powerful Slav empire to be formed Russian patriots saw at the same time a natural ally for Russia and a fervid enemy for Austria and Germany which, together with Italy, constitute the anti-Russian combination. The second reason was that Russia hoped, as a result of the Balkan war, to obtain Constantinople. The Russian government’s advice to the King of Bulgaria not to take Constantinople, together with the heavy losses sustained in attempting to get through the fortifications of Tchatalja, alone kept the Bulgarian army away from the capital of Turkey, and prevented the quarrel between the Slavs from becoming fiercer. The too-evident wish of the Bulgars to take Constantinople altered the attitude of Russian Slavophiles toward Bulgaria and afforded a pretext to Russian chauvinists for speaking of “Austrian intrigues in Bulgaria.” It was declared that Austria was inciting Bulgaria to enter Constantinople in order to foment Russian jealousy, and make misunderstanding.

But this Russo-Bulgarian quarrel is only a small part of the danger which threatens in the near future the peaceful development of the Balkan peninsula and the tranquility of Europe. The war with Turkey is still going on. Austria, instead of sending back to their homes the men she called to arms a few months ago, is increasing her armaments every day. All the while she is provoking Servia by nightly demonstrations of her warships before the capital, Belgrade, throwing the light of electric projectors on the defenseless town and surroundings.

Roumania is demanding more and more insistently an answer from Bulgaria. Turkey keeps on strengthening her defenses. The Balkan armies have been waging civil war among themselves. It is said: “Where the Servian mare passes no Bulgarian grass may ever grow nor Bulgarian speech ever be heard.” The awful visions of the past, when Bulgars, Serbs and Greeks fiercely slew each other, are so menacing that no journalist, to whatever party he may belong, can honestly remain silent as to that danger.

When the Servian troops entered Uskub, greeted by loud and joyful cries of “Hurrah” on the part of the Bulgars who came to meet them with unfurled Bulgarian flags, a Servian officer responded to the demonstration by saying that in Uskub there could be no room for Bulgarian “Hurrahs” or Bulgarian flags, as in that town there were no Bulgars, only Serbs. The next day the Serbs began to take away Bulgarian flags from the schools, they altered the names of Bulgarian families, making them Servian, and despite protest, insisted upon all official documents being issued in the altered names. These petty vexations were soon followed by real tragedies. Politicians, teachers and other important men began to disappear. Public rumor accused the Servian authorities of crime in this connection and of intriguing with the ill-famed Turkish hooligans, whom the Servian authorities for some reason or other had left at large.

Things did not get on better in Salonica between Bulgars and Greeks. During the Turkish regime the Bulgars had maintained, at great material and moral sacrifice, two or three newspapers of their own. But from the beginning of the Greco-Bulgarian occupation, when it would seem the Bulgarian press should have more liberty, the newspapers were stifled. The Bulgars resented this and once, at least, an armed conflict resulted. The question arises, what will the Greeks not be capable of when, having made Salonica entirely their own, they have completely under their control the Jews and Turks and other nationalities?

This war, which was fought for the realization of Balkan autonomy, shows a very dark side even to its friends. It is to be feared that this Balkan federation will not be able to secure peace between neighbors, or even blood-related and allied nationalities. History shows the futility of such combinations conceived merely for the purpose of conquest. The Austro- Prussian alliance, concluded in the year 1864, for the purpose of waging war against Denmark, did not prevent Austria and Prussia from taking up arms against each other two years later. The alliance between Roumania and Russia in 1877, for war against Turkey, ended in a way previously unknown to history; Russia appropriated one of Roumania’s provinces, Bessarabia. With this Roumania became one of Russia’s bitterest enemies and has ever since fostered the hope of revenge.

And even if a Balkan federation could outlive the disastrous state of murder and outrage which characterizes the Balkan-Turkish war to-day, it could not keep the people now engaged in that war from further conflict with each other. For, as long as the present officials, inspired by dynastic interests, remain at the head of the Balkan states, as long as the destinies of these states are controlled by the social groups who were the cause of the war against Turkey, and who insist on keeping alive every subject of misunderstanding between the masses, peace is not possible.

The present war will be no solution of the Eastern problem. I believe it will even make it more complex and perhaps lead to a further development of militarism, a higher cost of living and a sharpening of the class antagonisms which in late years have spread to every part of the world.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1913/v1n11-mar-15-1913.pdf