With drawings by William Siegel (many more in the PDF), the full text of this fine pamphlet by Luis Montes; a project of the Communist Party’s Labor Research Association.

‘Bananas: The Fruit Empire of Wall Street’ by Luis Montes. International Pamphlets No. 35. New York, 1933.

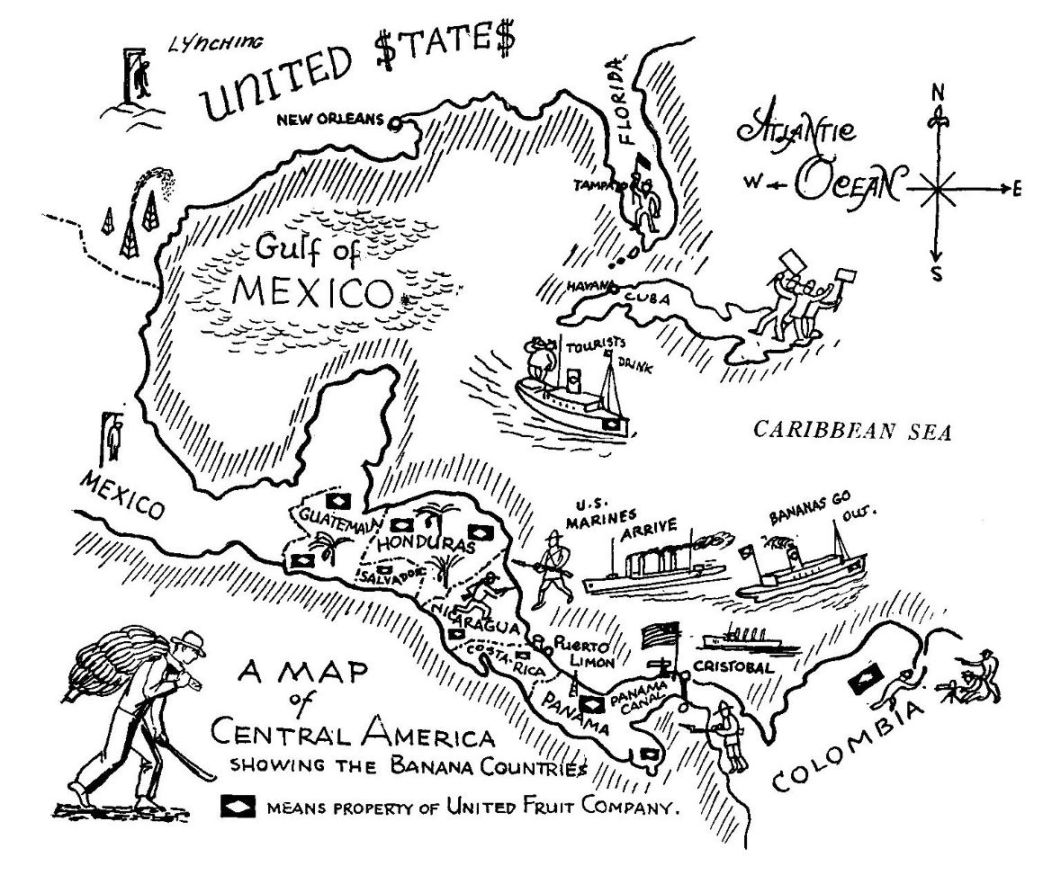

From the mosquito infested plantations of the Caribbean countries come the millions of bunches of bananas that are unloaded each year in the ports of the United States. The people of this country consume these bananas, joke about them, sing songs about them. But few realize what a monstrous system of economic exploitation and political domination has been built upon the production of this fruit. Few know that from it the greatest American imperialist enterprise in Central America— the United Fruit Co.—draws its profits.

It was largely through the establishment of the fruit plantation system, and particularly the cultivation of bananas, that the Caribbean Sea was converted into the “greatest of American lakes, and the countries which border these waters subjected to Wall Street rule. Guarding as they do the approaches to the Panama Canal, these countries have not only become an important source of tribute, but an area of extraordinary military significance for Wall Street. Thus the humble banana enters the arena of international politics as a factor of great importance.

The Home of the Banana

The principal banana producing countries are Honduras, Guatemala, Panama, Nicaragua, Colombia and Costa Rica—all bordering on the Caribbean. Along the flat coastal lands of these semi-tropical countries are located the enormous plantations from which bananas are shipped to all parts of the world. Dominating this huge area is the United Fruit Co., controlled by American capitalists. To ay that United Fruit rules a virtual Caribbean empire is no rhetorical exaggeration.

For in Caribbean countries the company (1932) owns or leases over 3,416,000 acres of land; owns or operates 1,768 miles of railway, 559 miles of tramway, 3,500 miles of telephone and telegraph lines. It owns more than $27,000,000 in equipment, enormous sugar mills, thousands of company houses. The company also has important holdings in Jamaica, the most important possession of Great Britain in the Caribbean. In addition it owns the “Great White Fleet” which with more than 100 ships practically monopolizes all shipping between the United States and Central America. In 1932, the capital and surplus of United Fruit Co. was about $145,000,000. It paid over $6,500,000 in dividends in 1932, nearly $11,000,000 in 1931, nearly $12,700,000 in 1930—all crisis years. Besides the history of its payments to stockholders includes many “extra” dividends and one “stock” dividend—free gift of stock—as high as 100% in 1921.

Until recently there were two other fruit companies attempting to compete with United Fruit in Central America. They were the Cuyamel Fruit Co. and the Standard Fruit & Steamship Corp. Cuyamel in 1929 was absorbed by United.

The Technique of Empire

In acquiring its enormous properties and in bringing about the economic and political enslavement of the Caribbean peoples, the American capitalist class has employed the experience and technique which it has acquired in the exploitation and robbery of the workers and farmers of the United States. Murder, intrigue and bribery were part of this technique. In this bloody business worthy allies were found in the corrupt landlords and the native capitalists of these countries.

A large part of the enormous concessions held by American capitalists in the Caribbean area was obtained by bribing the ruling political cliques. Where the ruling politicians, for one reason or another, balked the designs of the concession-seekers, it was a relatively simple matter to instigate or subsidize “revolutions” as, for example, in Panama, Costa Rica and Nicaragua, and bring more subservient groups of native politicians into power. Money invested in this way has usually brought fat returns in the form of land grants. Even where such ‘‘revolts” proved unsuccessful, the American imperialists frequently managed to profit by submitting enormous claims for alleged “property damages” incurred during the revolt—claims which have plunged the Caribbean countries deeper into debt and chained them more effectively than ever to Wall Street. Yankee imperialism has not only succeeded in limiting the economies of some of these countries to agriculture; it has even made their economic life dependent on a single product: bananas.

United Fruit Co. exercises effective control over politics in those countries in which it operates. Nor is the company’s relation to its puppet government concealed. Take, for example, the following, from the March, 1933, issue of the millionaires’ magazine. Fortune. Describing the days when Cuyamel and United were competitors, with the former attempting invasion of the latter’s field, the author writes: “United Fruit, master of the Caribbean, considered Cuyamel a trespasser in Guatemala…So Guatemala protested to Honduras. Both countries sent troops into the valley and there were two or three skirmishes.” Thus, unwittingly, the writer reveals the purely commercial nature behind many Central American wars. And with the acquisition of its competitor by United, presumably also went control of the government which had formerly opposed it at the bidding of Cuyamel.

Expropriating the Caribbean Farmers

Bordering the huge plantations of the United Fruit Co., there are still large tracts of land owned by peasants. The company is gradually acquiring these lands by various methods. The most commonly used device for expropriating the “independent” peasantry is the control of strategic water rights. By controlling the water supply by which the banana lands are irrigated, the company can frequently compel independent farmers to sell their lands to the company at a nominal price. Peasants who refuse to do so are intimidated and sometimes jailed on trumped-up charges.

By controlling railroad lines, roads and bridges, the company has another important device for expropriating the peasants. “Stubborn farmers,” who refuse to sell their lands to the company, frequently find that they have no means of marketing their products. Usurious loans and mortgage foreclosures are other methods used to deprive “independent” farmers of their lands and to convert the small proprietors into propertyless agricultural workers.

Slaves of the Company

In any United Fruit Co. center it is evident that bananas rule. The company controls presidents and priests; bank keepers and jail keepers; hotels and brothels. Its word is law. Upon its decisions depends whether tens of thousands of workers will work and eat or be blacklisted and thrown out of the company shacks.

There is no published record of the precise number of agricultu-ral workers employed on the United Fruit Company’s domains; but the best estimates place their number at between 140,000 and 150,000. About 40 to 50% of these workers are Negroes, brought in from Jamaica where the company also occupies a dominant posi¬ tion in the fruit and sugar trade.

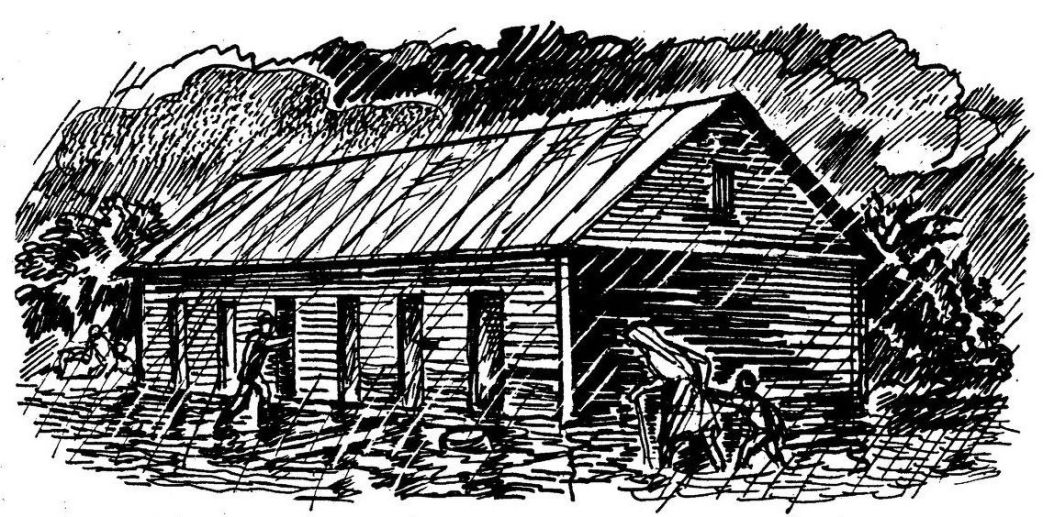

These workers are housed in flimsy company shacks, located in small towns, which differ but little from the company towns of industrial Pennsylvania. United Fruit towns, dotting the swampy coastal lowlands, contrast strikingly with those parts of the Carib¬ bean countries which have not yet been incorporated in the com¬ pany’s plantation system. To one coming from the highlands of Honduras, from the western coast of Guatemala or Costa Rica, the contrast is particularly sharp. From the wild forests and the primitive tropical life of the huge carelessly cultivated haciendas, the traveller suddenly enters a region reminiscent of industrial America. There are the same dingy company shacks, the same company stores, and the same luxurious bungalows reserved for “straw bosses.” There are the same foremen and overseers, even more brutal and arrogant in these surroundings because they are bossing “inferior” colonial peoples.

There is no tropical quietness in these United Fruit towns. Instead there is real American “tempo,” accompanying ultra-modern methods of exploitation. Locomotives continually pull out from stations; steamers leave modern wharves, all carrying the “green gold” to distant ports.

Outside the company villages, there are no huge factories, belching smoke. Instead there are the endless stretches of banana plantation, infested with malaria-carrying mosquitoes and poisonous spiders.

Every Port is a War Port

If you enter the banana kingdom by steamer, the first thing that meets your eye is the tall towers of powerful wireless stations. Near the stations are huge fuel tanks, holding quantities of oil which appear to be far in excess of the needs of the company’s vessels. The docks are as modern and well-equipped as the best transatlantic piers in New York City. These observations puzzle the visitor, until he remembers that all of these facilities for communication and transportation have been erected not only for the company’s fleet, but for the far larger and more powerful Gray Fleet, the warships of the United States navy. The visitor cannot help but realize that the docks, the fuel tanks, the powerful wireless stations are part of the immense military set-up whose center is the Panama Canal.

In view of the growing conflict between the United States and Britain, which has been reflected in the open warfare between Bolivia and Paraguay, it is necessary to remember the military importance of the Caribbean area. Jamaica and Trinidad, both British possessions in the Caribbean, are naval centers which the British fleet can use in operations against the Panama Canal. With the canal thus threatened, American naval strategy seeks every possible means of strengthening the military position of the United States in the Caribbean. An important link in the American system is the International Railways of Central America, which runs from Puerto Barrios, Guatemala, United Fruit Co. port on the Atlantic coast, through Guatemala and Salvador, to the United States naval coaling station of Cutuco on the Pacific. The intricate American military system in the Caribbean is important not only in connection with the growing danger of imperialist war, but also in relation to the efforts of the ruling class of the United States to smash the growing anti-imperialist struggles in Latin America.

On the Plantations

Surrounding the company towns and the shipping centers are thousands of square miles of banana plantations. These enormous stretches of carefully laid out fruit trees were not presented to man by nature. Before the banana trees could be planted, heavy tropical forests had to be conquered by workers laboring with hatchets and machetes. For clearing these wild dense forests, infested with poisonous snakes and mosquitoes, workers received even during the height of “prosperity,” wages ranging from $1.12 to $1.50 for a 10-to-12-hour day. On returning from Costa Rica recently, a student reported that peasants on plantations were getting ‘‘about $1 a week, and workers on United Fruit lines are paid 75 cents for a 9-hour day.” Since the beginning of the crisis, expansion has ceased, no forest lands have been cleared, and the majority of workers engaged in this occupation have been thrown out of work.

While some gangs of workers are clearing the forests, others are engaged in the difficult work of constructing roads and irrigation ditches to the newly-created plantations. Workers on road-building jobs are paid 20 cents a square yard. The maximum that can be earned at this rate is about 80 cents a day. Weeding and pruning is also paid on a piece-work basis and the usual wage for a day’s work is about 70 cents.

Captains and Contractors

In addition to being frightfully exploited, the workers are robbed of a large part of their wages by the “captain” and “contractor” systems. Instead of establishing uniform rates of pay for the same types of work, the company farms out forest clearing and road and ditch building jobs to contractors, who set up widely var5dng wage scales which make it easy for them to rob workers of part of their wages. In some regions workers engaged in road and ditch building are paid by the square yard; in others by the cubic yard. These measurements mean little to the majority of the illiterate workers, who are almost invariably robbed by the unscrupulous captains and contractors. These intricate methods of piece-work payment also make it difficult for workers to formulate uniform demands in their struggles against starvation wages.

Cutting

Cutting banana bunches from the trees is one of the most difficult plantation jobs. Branches of the tree must be carefully bent with one hand, while the bunches are being cut with the other. For this work, which includes hauling the bunches to the railroad, a team of workers receives about two cents a bunch. Other occupations — pushing the trailers, loading the railroad cars, etc.—are paid by the day, at a rate not exceeding $1.50. In 1931, it was reported that for railroad or emergency work in Honduras, laborers were being paid on an average of $1.12 a day. Since 1929 wages have been cut about 60%.

Dividing the Workers

In an effort to keep Honduran workers from developing organized struggles for better conditions, the company deliberately attempts to play off native mestizo workers against the Negroes, who are largely imported from Jamaica. But here the method is different than in the United States, where the Negroes are treated as an oppressed people and discriminated against at every turn. By conceding slightly better conditions to Negroes—such as assigning them shacks with mosquito netting, giving them the few better paid jobs, granting them preference in employment—the United Fruit Co. has created much resentment among the native workers. It has also skillfully used the speed-up method to carry through this division. In the loading of bananas on the steamer, the contractor will place Negroes along the conveyor at strategic points to set the pace. Being huskier and stronger than the natives they work faster. The loading of any single steamer must be done at one stretch—usually from 12 to 16 hours, for which a maximum of $2 is paid. The contractors likewise hold a firm grip over the Jamaican Negroes by the constant threat of deportation.

Writing from Jamaica in February, 1931, Harvey O’Conner reported “United Fruit plantation workers, toiling under a broiling sun for a mere 37c for nine hours’ exhausting labor. Or…Negro women in Kingston and Port Antonio who carry 100 heavy stalks on the wharf for 25c.”

He told of piece rates for men being cut from 67 cents to 50 cents for 100 stalks, and for women from 37 cents to 2 5 cents.

The tactic of dividing the workers has thus far met with some success, and many of the mestizo workers resent the presence of Negroes and regard them as “foreigners” who have come in to take away jobs from “natives.”

But the local revolutionary trade union movement points out that the vast majority of the Negroes are as brutally exploited as the natives. It attempts to organize both mestizo and Negro in joint struggle for better conditions.

How the Workers Live

Both Negro and white workers live in filthy barracks, consisting of six or eight rooms. Each room houses an entire family. There are practically no provisions for sanitation or ventilation. During the torrential winter rains, the houses look like barges stranded in a sea of mud. In these stagnant pools, malaria mosquitoes breed and carry this dreaded disease into practically every barrack. The prevalence of malaria makes adequate sanitation and medical treatment one of the major demands in the struggles of the plantation workers.

In some regions the company has erected hospitals, for the maintenance of which two percent is deducted from the workers’ wages, sometimes up to $5 a month. These hospitals, however, are reserved for so-called major illnesses while the malaria victims are casually treated in the plantation “dispensaries.” The uniform cure for practically all ailments is quinine. One worker informed the writer that he had once swallowed a fish-bone and had gone to the dispensary to have the bone removed from his throat. Without examining him, the doctor gave him a dose of quinine. When the patient objected, he was unceremoniously thrown out of the dispensary.

Medical treatment in the hospitals is scarcely better. Conditions in many of them are so bad that workers with serious illnesses have sometimes “escaped” from the hospital and returned home.

The “Comisariados”

The company store is one of the institutions which the company has brought into Central America from the feudal mining and textile company towns of the United States. The system is even more complete and widespread in the Caribbean. Workers are paid in scrip which is valid only at the stores (comisariados) maintained by the company. Since the scrip is exchangeable only once a month, the workers find that they have used up all their credit long before the end of the month. Through this institution the workers are, kept in perpetual debt to the company and in a virtual state of peonage.

Struggles of the Banana Workers

The tens of thousands of native and Jamaican Negro workers, employed on the banana plantations of the Caribbean countries and exploited by the United Fruit Co., constitute the most important working class unit in Central America. In Colombia also they form an important section of the working class and are destined to play an exceedingly important part in the anti-imperialist struggles in the Caribbean.

The banana workers have, indeed, already engaged in significant mass struggles. Current developments indicate that these struggles will be more extensive in the near future, especially since the struggle in Cuba against Wall St. imperialism which has had a profound effect in the Latin-American countries.

Thus far the struggles of the banana workers have largely centered around wage reductions and unemployment. Since the beginning of the crisis—and the crisis developed earlier in Latin America than in the more advanced capitalist countries—wages have been slashed from 40 to 70%, and nearly three-fourths of the working population has been forced into the ranks of the unemployed.

The Santa Marta Strike

The first major struggle against these conditions developed in Colombia in November, 1928. The strike began as a struggle for improved sanitation on the plantations but quickly developed into a broader fight for higher wages, a weekly pay day, one day of rest in seven, accident compensation, and abolition of the scrip system of wage payment and company stores.

The strike was badly led by an organization known as the Union Sindical, which failed to develop democratic strike committees and which displayed other weaknesses. Nevertheless, the enthusiasm of the workers was so great that the movement, which had started as a walkout of 5,000, soon embraced the entire 30,000 workers in the area. Even the poor and middle farmers and the small shopkeepers joined hands with the strikers.

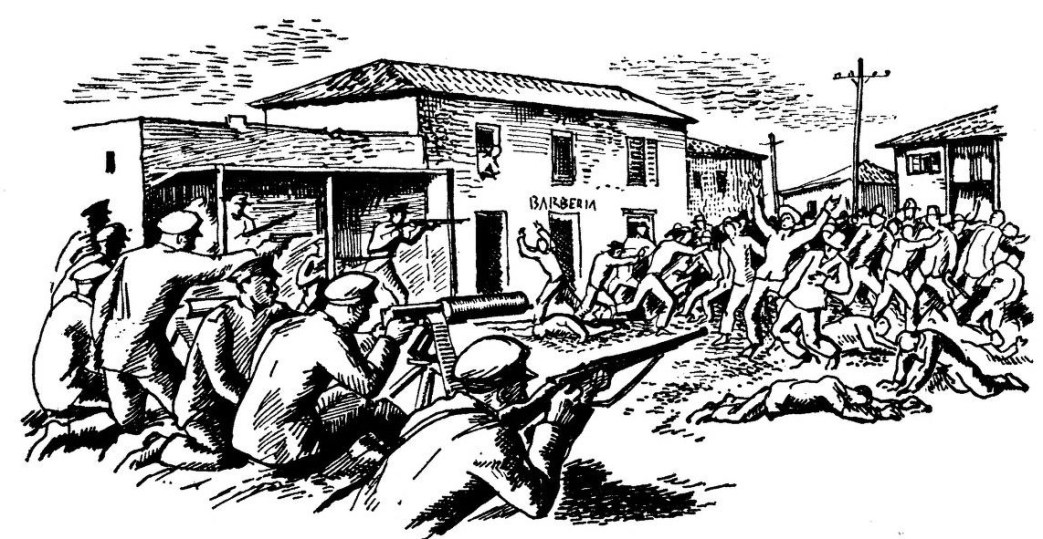

Agents of the United Fruit Co. and their local government allies were panic-stricken. Cables were hurriedly exchanged between the Colombian government and Washington. Several American warships were reported in the waters of Santa Marta at the time. The government mobilized all troops in the vicinity.

Although the strike reached such a high level, it failed on account of the weakness of its leadership. The heads of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, to which the strike leaders belonged, failed to mobilize mass support in favor of the strike. Instead they timidly sent telegrams to the strike leaders instructing them not “to forget that the strike was simply an economic struggle.” At this point, some of the leaders deserted the strike; the others were isolated and confused.

On the night of December 5, the government declared martial law in the strike area. The next day, government reinforcements sent in under the leadership of General Cortez Varga opened fire on a strike demonstration near the railway station of Cienega and shot hundreds of unarmed workers. The heroic struggle of the Colombia banana workers was drowned in blood. The date of this bloody massacre has become a day of mourning and struggle for the revolutionary workers of the Caribbeans and South America. Reliable reports give the total killed in all shootings during the strike as about 1,000 banana workers and small farmers, while 3,000 were wounded and some 600 arrested.

The Struggle in Nicaragua

In Nicaragua the struggle of the workers and peasants against United States imperialism assumed the form of open warfare. For years the armies of Sandino heroically resisted the armed forces of the United States. This protracted fight was limited in scope, however, on account of the petty bourgeois leadership of Sandino. Instead of struggling against the landowning and bourgeois national agents of imperialism and fighting for the needs of the workers and peasants, Sandino merely demanded the expulsion of the American marines—as though the presence of the marines constituted the sum total of imperialist oppression. The marines have been withdrawn from Nicaragua, and Sandino has capitulated. But the brutal exploitation of Nicaragua continues.

A more genuine blow at imperialist rule in Nicaragua was struck in April, 1931, when the armed struggles spread to the banana plantations of the Standard Fruit & Steamship Corp. In the clashes that followed, eight agents of the company were killed. It is these workers of the eastern banana plantations, mines and railways, who, allied with the peasantry, will carry on a heroic struggle for the complete and genuine national independence of Nicaragua.

Struggles in Other Caribbean Countries

Plantation and port workers in Panama and Honduras have also participated in important anti-imperialist struggles. In Guatemala the revolutionary movement achieved some influence, particularly in Guatemala City, but was practically wiped out by a bloody campaign of repression and terror. In Costa Rica, a country completely under United Fruit Co. domination, the movement is in its formative stages.

A series of strikes and peasant struggles have taken place in the province of Chiriqui, Panama, where at times the struggle embraced all the workers in the industry—port and railway workers as well as the workers on the plantations. The strikes were broken by the troops of the native puppet government of Wall Street.

The most important struggles have taken place in Honduras, the largest and most important banana-growing center. Here the struggles affected the entire plantation area, culminating in an important strike of dock workers in Tela in January, 1932. Resistance to a 20% wage cut for plantation laborers and a 25% cut in prices to poquiteros, or banana growers, who were selling their products to United, met with bitter opposition on the part of the company. Pres. Collindres sent in troops, martial law was declared, and the strikers cautioned to accept the slashes in the “national interest.” Failing this, one of United’s armed gangs, which roam the banana fields for just such deeds, kidnapped five strike leaders and deported them to Puerto Barrios. Refused entrance there, the workers were brought to an aviation field in the San Pedro Sula and sent to Salvador in a company plane.

Armed uprisings, led by bourgeois demagogues aspiring to political office, have enlisted widespread support among the workers and peasants. The Communist Party of Honduras, despite its heroism under brutal terror, has not, as yet, been able to play an independent part in these armed struggles.

With the exception of a few demonstrations by American workers, notably at the United Fruit Co. docks in New York and Philadelphia during the Santa Marta strike, little aid has as yet been rendered by workers of the United States in these struggles.

The White Fleet

The exploitation of the United Fruit Co. is not limited to the natives of the Caribbean. The ships of the White Fleet, which monopolizes the trade in “green gold” and is owned by the United Fruit, are known to North American sailors for their rotten conditions. For a working day of from 12 to 14 hours, the wages are about $40 a month. Food is scant and unwholesome and the sailors’ quarters crowded and filthy.

Realizing that the sailors on these ships offer a splendid opportunity for welding a bond of solidarity between the workers of the Americas, the company has saturated the fleet and the ports with spies. Stool pigeons are planted on every steamer that carries bananas; crews are systematically replaced after every trip to prevent any organization on board. So careful is the company in guarding against militant organization, that it permits only “trusted” drivers to haul the bananas from the pier to other trucks no more than loo yards away. Moreover, United Fruit Co. has employed the Sherman Service, notorious labor spy agency, in order to defeat efforts of its transport workers to organize.

The Marine Workers Industrial Union, however, has found ways of evading this elaborate spy system, and is beginning to build its organization aboard the White Fleet. This should serve as the beginning of a much needed bond of unity between the workers of the United States and of South and Central America.

Solidarity Across the Americas

The story of the banana is the story of a whole imperialist empire. The same capitalist class which in the United States exploits the vast majority of the people and condemns millions to starvation and unemployment, extends its domination into the semi-colonial countries of Central America. To protect the profits reaped from the banana plantations and other enterprises in these countries. Wall Street arms and prepares to fight Great Britain, its chief rival.

The Yankee exploiters add to their power and strength as a result of their robbery of the Latin American masses. They use this added power to grind down even further the standard of living of the masses of the United States. American workers should, therefore, hail every struggle of the masses of Latin America against the common enemy and give such fights their direct material and moral aid. The Latin American workers have been more advanced in this respect. They have recognized and hailed almost immediately every upsurge in the American labor movement. For they realize that their own freedom is closely linked to that of the working class of the United States.

Communist Parties and revolutionary unions have been formed in Colombia, Panama and Honduras, the most important banana countries, despite the tremendous difficulties and obstacles put in their way by the United Fruit Co. and the native governments. In the revolutionary movement in these countries the American workers have a powerful ally in the struggle against Wall Street. But this alliance can only be forged in day to day assistance given to the young revolutionary movement of the Caribbean. It has been illustrated most recently in the support given to the anti-imperialist movement in Cuba, following the overthrow of the Machado terror. In supporting the real revolutionaries of Cuba the American workers are helping to extend the struggle against imperialism.

In the United States, the Anti-Imperialist League, an organization of American workers and colonial workers living here, attempts to organize support for the struggles in the Caribbean, to bring these struggles closer home to the American workers. The workers of the Caribbean look eagerly for every offer of aid from the workers to the North. By building this solidarity across the Americas, the workers will be able to overthrow the rule of imperialism.

The Labor Research Association was established in 1927 by CP publisher Alexander Trachtenberg “to conduct research into economic, social, and political problems in the interest of the American labor movement and to publish its findings in articles, pamphlets and books.” Rand School of Social Science veterans Scott Nearing, Solon De Leon, and Robert W Dunn along with Communist writers and labor researchers Grace Hutchins and Anna Rochester were its leading early members. Known for its Labor Fact Book almanac, published by International Publishers from 1933, the LRA has produced a number of invaluable texts for researchers and activists of the US labor movement.

PDF of full book: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/international-pamphlets/n35-1933-Bananas-Luis-Montes-drawing-by-William-Siegel.pdf