Most of us, if we are familiar with the work of the great William Gropper, know his drawings and cartoons. The prolific political artist was also a painter, with a 1936 showing at the American Contemporary Art Gallery reviewed by Harold Rosenberg–later art critic for the New Yorker.

‘The Wit of William Gropper’ by Harold Rosenberg from Art Front. Vol. 2 No. 6. March, 1936.

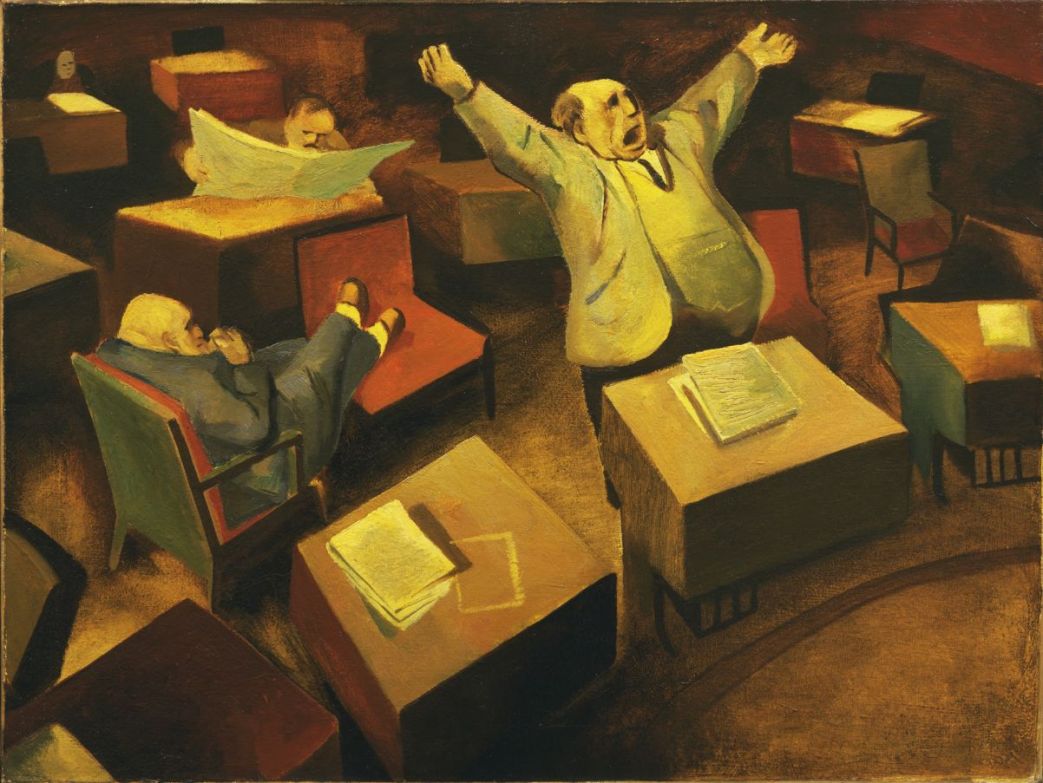

CONTRARY to what some people would expect from a left-wing artist. one of the outstanding characteristics of Gropper’s show at the A.C.A. Gallery is its great variety in all respects—subject matter, mood, manner and even medium. What the show says to the audience is: It is no longer a question of crudely conceived “left-wing” pictures of bread-lines, pickets, mounted police; everything of value in the art of painting is becoming the property of the revolutionary movement. It will soon be possible to speak of a revolutionary landscape, of a revolutionary still-life. Gropper’s show is a single action on the part of a revolutionary artist. On one wall is a selection from his famous political cartoons, humorous, biting, and scandalous attacks on the rulers of American society. Some of these satirical themes recur in the paintings: “The Senate,” “Art Jury,” “Gentleman,” “A Judge.” But the handling of the satirical painting “The “Senate” relates it to the non-satirical painting called “Strike” (although the static, somnolent character evoked in the first by certain cubistic devices is replaced in the second by an energetic disposition of forms), and the energy of “Strike” carries directly into such pieces as “Suicide,” “Klansman,” “Survivors,” painted from a totally different technical angle and in a mood remote from “modern” painting. Thus, in spite of obvious influences from such dissimilar sources as Ryder, Breughel, Japanese painting, primitive art, Daumier, Forain, cubism—the show creates a remarkable effect of unity and a thoroughly integrated impact upon the sensibilities.

Once this single communicative effect of the show is established, it is possible to see how non-social paintings like “Burning Wheat,” “Tiflis—U.S.S.R.,” “Picnic,” “Landscape,” “Still Life,” “Village Character,” “Gentleman,” etc., enrich the cartoons and political paintings “Strike,” ‘““The Senate,” “Soup,” “Suicide” with local color and a world-environment, at the same time that they derive their association with the political art a special meaning which they could not possess in a roomful of street scenes and apple-arrangements. Paintings which belong together have a cumulative power. The principle—art is propaganda—does not imply that each individual work of art must contain in itself a complete argument leading toward a revolutionary conclusion. The principle—art is propaganda—recognizes the fact that the picture-world of the painter includes within it elements of many kinds, some confined to the world of simple appearance, some introducing into appearance action-motives and a critique of values; and that this picture-world, as an entirety, deflects the mentality of society in one direction or another. This is true of the art of painting as a whole and it is true also of the complete works of the individual painter.

Gropper’s exhibition proves that the revolutionary painter, far from being a grim specialist of a world seen in a contracted focus, is precisely the major discoverer of new pictorial possibilities as well as of new uses for the old.

There will be two chief points of criticism against Gropper–(1) that he has discovered no new formal or technical approach to the problem of revolutionary painting and (2) that his paintings themselves show a facility, a virtuosity even, of application which is lacking in profundity.

To the first criticism, it is necessary to respond: Yes, it is true Gropper has developed no new technical apparatus €specially designed for use in painting revolutionary pictures. It is true he openly employs the devices of Breughel, Ryder, cubism, Japanese landscape art, Forain and Daumier; in fact, there are very few painters who reject to such a degree any effort to conceal their origins. But what does this mean? Does not the very frankness with which he loads revolutionary material into the old apple-carts of art-technique constitute an assertion that these vehicles have come down the same historic road? Does not the whole exhibition indicate that the art developed in and adopted by modern civilization since its beginnings possesses a natural continuity with the revolutionary impulse of the art of today and tomorrow? Painting, filled with a new perspective, will develop new techniques, just as a society organized on the basis of new relations will develop new machines; but, in this development of the new, that which is still productive in the old plays an important, if not a decisive, part. Though Gropper has not yet developed a new form for revolutionary painting, he has, by his easy and graceful mastery of the materials of social struggle, by his presentation of it, as it were, from the inside, without strain, carried forward the possibility of technical discovery in revolutionary art. Instead of waiting for a revolutionary esthetic to grow out of the air, or attempting to distinguish revolutionary art from other types of art by the rejection of all technical values, he has contributed to revolutionary art and to its dynamic history by simply painting revolutionary pictures of excellent quality. If this is a simplification, it is a simplification that had become very necessary.

The easiness and gaiety of Gropper’s pictorial communications, his unworried eclecticism, will create in some minds an impression of superficiality and artistic carelessness. This question of superficiality is by no means an uncomplicated one. Granted that, on a few occasions, thinness of paint-quality and slight weaknesses in the internal development of form disturb the trained eye; granted that the adaptations are, in paintings like “Klansman” and “Burning Wheat, somewhat too reminiscent of their originals, and that the mood inherited by the “Klansman” goes too far toward romanticising, involuntarily, the abject and contemptible figure of the hooded nightrider. Such deficiencies may be validly noted; yet they fail to form a basis for condemning Gropper’s work. Easiness of manner and even a certain type of carelessness are not inconsistent with serious purpose; any more than hard work and a homeopathic brooding over the response a work of art will achieve for itself are inconsistent with pretentiousness and bad faith. One has only to contrast the easiness of Gropper with the labored yet slick finish of Joe Jones to be convinced on this point.

The busy Gropper makes his statement as best he can and goes ahead to something else. From his training in caricature he derives a decisiveness of purpose which converts all his technic acquisitions into instruments with a special preconceived utility in each case, does not stop and grow heavy over painting, because what he is concerned with is some dominant feature of the subject-matter which he has isolated. Some. times this essential aspect seems so completely rendered that other qualities are neglected (E.g. F.D.R.’s Speech). By out of this coherent purposefulness of each painting arises a unity remarkable within such a multiplicity of modes, And often, as in “Psychiatrist” and “An Jury,” the essential caricature combing with lyricism, movement, and fantasy to produce an inescapable judgment which, seems almost as if it emanated from the best intelligence of society itself, a deft profundity of the enlightened mind, in comparison with which the ponderous profundities of our more “spiritual” art seem to belong to the drowned confusions of some earlier day.

Art Front was published by the Artists Union in New York between November 1934 and December 1937. Its roots were with the Artists Committee of Action formed to defend Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads mural soon to be destroyed by Nelson Rockefeller. Herman Baron, director of the American Contemporary Art gallery, was managing editor in collaboration with the Artists Union in a project largely politically aligned with the Communist Party USA.. An editorial committee of sixteen with eight from each group serving. Those from the Artists Committee of Action were Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Zoltan Hecht, Lionel S. Reiss, Hilda Abel, Harold Baumbach, Abraham Harriton, Rosa Pringle and Jennings Tofel, while those from the Artists Union were Boris Gorelick, Katherine Gridley, Ethel Olenikov, Robert Jonas, Kruckman, Michael Loew, C. Mactarian and Max Spivak.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/art-front/v2n04-mar-1936-Art-Front.pdf