Dora Montefiore, the English-Australian suffragette, Socialist, and founding Communist, reflects on her visit to New York City and contrasts her tour of Wall Street’s stock exchange with her walk through the streets of the East Side.

‘Exploiter and Exploited: An English Socialist’s View of New York’ by Dora Montefiore from The New York Call. Vol. 3 No. 207. July 26, 1910.

One of the most torrid days this summer in New York I journeyed down to Broad street in order to watch from the gallery of the Stock Exchange the effect of a minor crisis or panic on the buyers and sellers of stocks. It is only by favor of a member of the exchange that one of the public may stand even in the general gallery within its sacred precincts; for fear reigns in the hearts of these worshipers at the shrine of Mammon, and they dread lest a bomb, or other swift missile of mischief, might disturb the celebration of their somewhat clamorous rites.

As my courteous guide and I stood for a moment outside the door, he explained that I might expect unusual excitement, as recent legislation in Congress against raising railway freights and traveling rates. had caused a sudden depression of railway and steel stocks, and the alarmed public were selling rapidly. As he finished his little explanation, and opened the thick heavy door to let me pass through into the gallery, I understood why he preferred to speak outside and not inside the shrine; for the babel of a mad house smote upon our ears, and hoarse, guttural, clamoring voices rose, and rocked, and reverberated ceaselessly through the lofty stock market. Try and imagine the chorus from the ape-house and parrot house at the zoo blended with the inchoate utterances of the liveliest wards in Bedlam, and you will have some idea of the simmer of senseless sound, accentuated with yapping yells, which form the harmonies of the Broad street chorale.

Young and Old Maniacal.

Round sixteen different stands were grouped men, young and old, who constantly received written messages from the hands of khaki-clad messenger lads. Other men watched anxiously the messages of the tapes, as they unwound rapidly under glass shades. Others were frantically pressing t ward the east side of the hall, where the cables to London were being operated, and where replies from that city were received five minutes after the New York message had been sent. Others stood in groups, notebook in hand, repeating monotonous cries, seemingly heedless whether they obtained attention or not. Hither and thither ran the messenger lads; louder and louder rose the raucous, turgid crier; higher on the floor lay the heaps of torn paper. And still the swaying, shouting, perspiring, buying and selling mass of men, young and old, yelled and yapped, and filled to the dome of the building the space around and above them with bestial, Bedlamite clamor.

Selling Others’ Labor.

And these, I thought, be the lords of finance; these be they whose luxurious dwellings adorn Fifth avenue and Newport. The daughters of these dealers in stocks are decked with the daintiness brought from many far lands, and they marry princes, dukes and earls from the old countries Europe because they bring in their dowers many millions of dollars. By what, I mused, is the wealth in which these mad men deal: and how did they obtain the values which they buy and sell in Wall street and Broad street with the feverishness of frantic fiends? They are dealing in the shares of coal and of iron mines and of railways that have opened up and increased ten thousandfold the wealth of their country–railways which they did not make with their own hands and mines in which others have sweated and lost their lives. And, because these men of finance have traded on the ignorance and the economic helplessness of the immigrant Italians, Poles, Jews, Lithuanians and Scandinavians–who have done the pioneer work of the country–and have cunningly robbed them of the greater part of their wages; these men of finance are able to hold, and manipulate, and sell for inflated profit, and buy in again at bottom prices shares in the wealth created by these ignorant exploited alien toilers.

And, as I watched and wondered, I tried to think of these men in their saner moments and attempted to picture them in their family circles, in their hours of recreation, in their moments of aspiration. But I failed to picture them otherwise than with waving arms and distorted faces, and uttering bestial, yapping cries. And I turned away, saying in my heart, “These men and their monstrous worship are far removed from the purpose of life.”

Through East Side Bedlam.

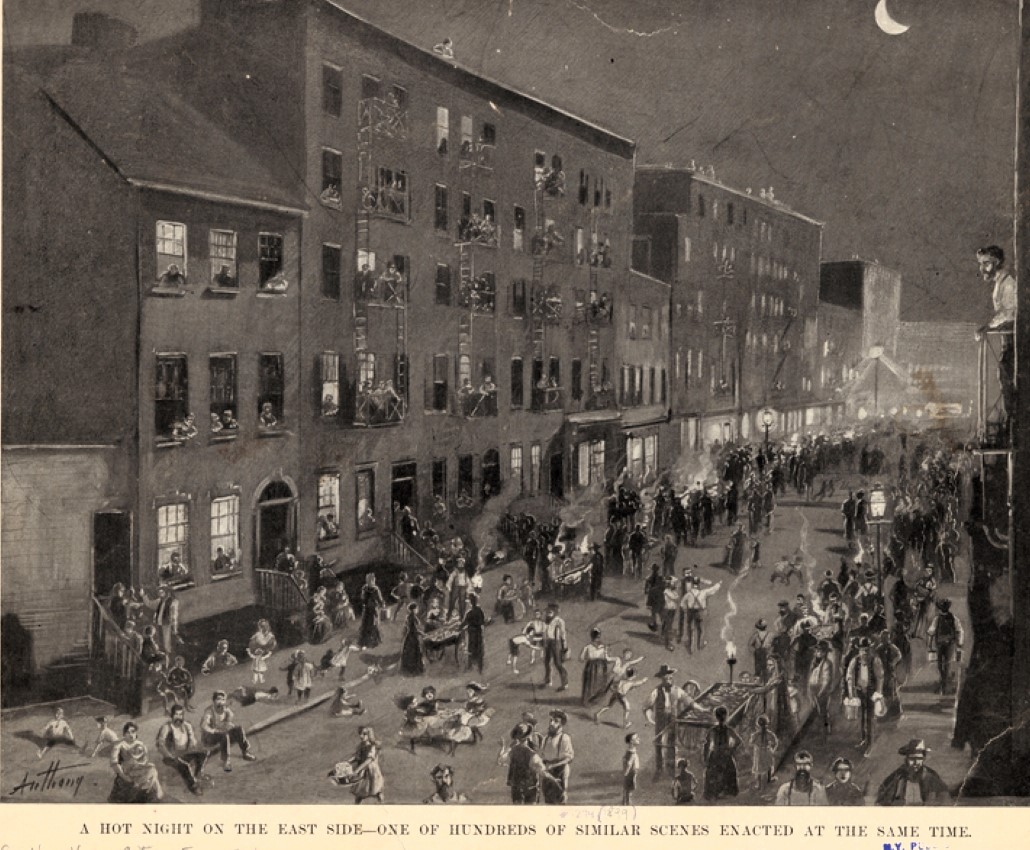

And on a breathless and torrid night I walked with friends through the stifling shadows of New York’s East Side, where dwell the aliens who toil during the day in sweatshop, factory, and in the sun’s fierce glare, to pile up riches for those who live softly and fare sumptuously on the West Side. In Grand street, the main artery through this cosmopolitan city within a city, gaudy shops displayed wax mannikins garbed in cheap imitations of Broadway and Fifth avenue fashions, and tempted from the pockets of pale working girls the dollars that should have been spent on wholesome food or more airy lodgings. Five and ten cent shows with flaring lights and strident-voiced advertisers were another means of getting back into the pockets of the capitalists the wretched wage of the worker. Once off Grand street and the glare of its electric lights, we plunged into a tangle and turmoil of side streets that for noise and filth beggared description. Along one narrow street ran an elevated railway on a level with, and within a few inches from, the second-floor windows of the tenement houses on either side. Most elevated railways run along the middle of the street, leaving the sides of the streets and the sidewalks clear. This horror covered the whole street and sidewalk, and as we crept along among its iron struts the passing trains thundered overhead, and every girder, and rivet rattled and quivered in grinding. nerve-racking response.

“Pushcarts” lined most of the streets, and everything to eat, to wear, and to use was sold on these hundreds of hawkers’ barrows. The shops also seemed to have turned all their wares, from fish and fruit to razors and false hair, out on their stalls facing the sidewalks; while vendors of lemonade, of slices of pineapple and watermelon filled in the interstices between the untended perambulators. where sleep the babies, and the ubiquitous, half-clothed gamins who dodged in and out between pedestrians and peddlers, picking up a peanut here or an unconsidered trifle there, and learning the one scientifically taught lesson of the street–how to live by their wits. Each doorstep was crowded with men, women, and children, while old ones dozed against open doors, and lads and lasses sat, hand in hand, in the shadows. The condition of at least eight women out of every ten belied the Rooseveltian cry of “race suicide;” and the whole scene was that of intimate domestic relations turned out of doors on the sidewalk. Of the state of those sidewalks, and of those cobble-paved streets, perhaps the less said the better; for my woman friend and I had to draw our skirts aside at critical moments; while we readily believed what one of our men escorts, who had lived for some time in a settlement in these parts, told us that he could trace his way blindfolded through the various streets guided by his sense of smell. Our goal was Seward Park, an open space of about three-quarters of an acre, round which stand grouped the offices of the Yiddish and of the German newspapers, the Children’s Recreation buildings, the Sixty-second Public School, the Carnegie Library, and the Jewish Educational Institute. Here were light, space, and–in the buildings–an ideal of beauty after the darkness, the stifling narrowness, the festering foulness of the side streets. An arched marble loggia of classic design gave both beauty and dignity to the facade of the Children’s Recreation building where baths, swings, and playground seemed at 9:30 p.m. magnificently popular. Each seat in the small park was filled with a family party, and here again the well-filled perambulator stood at ease on every side. At the Sixty-second Public School a graduation festival (for pupils graduating to the high schools) was in full swing; and in its really fine auditorium an audience of some eight or nine thousand parents and friends sat, watching admiringly, in a Turkish bath atmosphere, the rhythmical movements of small Jews, Italians, and Poles, who, in white dresses and with beribboned hair, disported themselves on the stage.

Library Buildings Inadequate.

The glow from the roof gardens of the Carnegie Library and of the Educational Alliance next attracted our attention and we entered the open doors of the latter institution with the intention of using the elevator, in order to study at close quarters this original way of providing breathing spaces in sultry weather for the over-worked and overcrowded. But before crushing with the gasping immigrants into the crowded elevator we had the advantage of a few minutes’ conversation with one of the superintendents of this entirely Jewish institution, and learned from him that if two-thirds of the actual immigration ceased at once they would still be overcrowded in their district, and that they needed at least ten similar institutions to cope, in any way, with the immediate needs of the neighborhood. The locale of the Educational Alliance, which was the “charity” of wealthy Jews, is a large corner house of many stories, with the ordinary club, reading, class and recreation rooms, besides the roof garden, which presented an extraordinary scene, brilliantly lit, and crowded with Continental Jews of every age. In one corner pasteurized milk was being sold at 1 cent a glass, in another a group were playing cards, some lay prone on benches, some read the news aloud to a listening group; the children moved about languidly. and the exhausted parents rested in every attitude of extreme abandon. This roof garden is open about seventy-five days in the year; and the average daily attendances in 1908 were, according to the report of the alliance, 4,125. This report also states most naively that “a vigorous educational campaign on the evils of residence in a congested district is carried on through the information bureau.” As if any human being, whether Jew or Gentile, would prefer the neighborhood of Seward Park to that of Central Park, if economical necessity did not chain him to the evils of the one and forbid him the advantages of the other. The East Side is, as a matter of fact, the dumping ground for the cheapest form of human labor in New York; cheap because, as Boudin has written in his “Theoretical System of Karl Marx,” “The producer has to pay the value of the labor necessary to produce this labor power, or, in other words, he has to pay in the form of wages the amount of goods which the laborer consumes while exerting his labor power. This amount will vary, of course, with the standard of living of the working men. But it will be invariably less than the amount of goods produced by the laborer in this exertion of his labor power.” In other words, if these poor aliens did not exist, in their swarming, teeming millions under conditions compelling them to sell their labor for a price which allows a substantial surplus value to their exploiters, the wealth they create could not be gambled huckstered and chaffered on the exchanges of the world. Nothing but ignorance and lack of imagination on the part of the exploited stands between them and the possession of the tools with which they produce wealth for others to enjoy. Labor, once conscious of its power, its real value and true relation to the wealth it creates, will, before long, rise in its own inherent might, and will sweep away the madhouses where the gamblers traffic in paper values. The commerce, traffic and civilization of the world could continue to be carried on without the howlers on the stock market; they could not be carried on without the workers, who are at present taught in philanthropic educational alliances and kindred institutions that capitalism is a form of production inherent and permanent, and that the duty of workers is to take cheerfully the market price of their Iabor, and humbly and thankfully accept the charitable cent returned to them by their employer out of the dollar they have earned for him. Therefore, are all settlements and settlement workers declared by a capitalistic society to be worthy of support and encouragement, because they help to keep things safe and comfortable for the capitalist.

Take Back Your Own.

And therefore is the Socialist interpreter and teacher anathema and a stumbling block unto the same capitalistic society, because they declare unto all workers: “Arise and stand up like men and women, and sweep aside those who rob you of the full product of your labor. Take possession of the railroads, the mines, the factories, and use them for the benefit of all, instead of allowing them, as now, to be used for and gambled in for the benefit of a privileged few. Start out, ye teeming millions of toilers on a campaign not only against the evils of residence in a congested district, but on a real campaign against the evils of using a hundredth part of the wealth you create when you should be using the whole. Leave the wilderness in which you have been wandering so many years, and prepare yourselves and your children for the final and great adventure of humanity–the entering into the promised land, where the struggle for the lower and material life being ended, the real, conscious. upward struggle for the higher and nobler life on this earth will begin.”

The New York Call was the first English-language Socialist daily paper in New York City and the second in the US after the Chicago Daily Socialist. The paper was the center of the Socialist Party and under the influence of Morris Hillquit, Charles Ervin, Julius Gerber, and William Butscher. The paper was opposed to World War One, and, unsurprising given the era’s fluidity, ambivalent on the Russian Revolution even after the expulsion of the SP’s Left Wing. The paper is an invaluable resource for information on the city’s workers movement and history and one of the most important papers in the history of US socialism. The paper ran from 1908 until 1923.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-new-york-call/1910/100726-newyorkcall-v03n207.pdf