James Dugan, film critic for the New Masses, corrects the account of the risible ‘Gone With the Wind,’ one of the most famous and popular movies in U.S. history. Part of a series, this article refutes the film’s portrayal the burning of Atlanta and the character of Sherman’s army.

‘Facts on the Wind’ by James Dugan from New Masses. Vol. 34 No. 5. January 23, 1940.

“Pierce the shell of the CSA,” said General Sherman, “and it’s all hollow inside”… which might also define the factual basis of “Gone With the Wind.”

THE four-million-dollar film about the Confederacy, Gone With the Wind, has become a major national issue, the subject of a vigorous attack by democrats, and the favorite parlor chatter of the upper classes. The Gallup poll has indicated the size of the ballyhoo in the claim that over fifty million people are eager to see the picture. Although the film deals primarily with historical events it has been presented in Hollywood’s usual guileless fashion as a great romance. Of course, the curious fact appears that there are two versions of the picture, one for the South and one for the North, and the advertising material is cut to two fits. Lacking knowledge of the Southern version, let us deal with the edition prepared for the North.

There are three historical events treated prominently in the film: the siege of Atlanta, Sherman’s march to the sea, and the Reconstruction era in Georgia. The treatment is careful in avoiding direct historical incidents, and the falsification in the picture is made by acceptance and inference. The story is told from the point of view of Scarlett O’Hara’s plantation-owning class.

SLAVEOWNER MINORITY

The two plantations seen on the screen, Tara and Twelve Oaks, belong to the small fraction of extremely wealthy Southern planters. In the slave states in 1860 there were only eight thousand owners, holding more than fifty slaves apiece, out of a total slaveholding group of 347,525. The middle group numbered 83,000, or those who held from ten to fifty slaves each, and the small fry, or those holding under ten slaves, totaled 254,000.

The total population of the slave states in 1860 was nine million, of which 3,500,000 were black slaves, owned by the 347,525 masters. Gone With the Wind represents this small group of big slaveowners–the Wilkeses and O’Haras who instigated the bitter war. They did not represent the 5,500,000 whites in the South any more than they represented the disfranchised Negroes, for only one slave state, South Carolina, produced a majority at the polls for secession. In the election of 1860, in the South only, Breckenridge, the secessionist candidate, polled 570,000 votes, against the total of his three non-secessionist opponents, including Lincoln–683,000. It is interesting to note that Margaret Mitchell’s own state of Georgia with a million population cast only sixty thousand votes in this election. How much worth saving is there in a civilization in which 6 per-cent of the population decides all questions? How much truth is there in a picture told from the point of view of eight thousand big slaveowners?

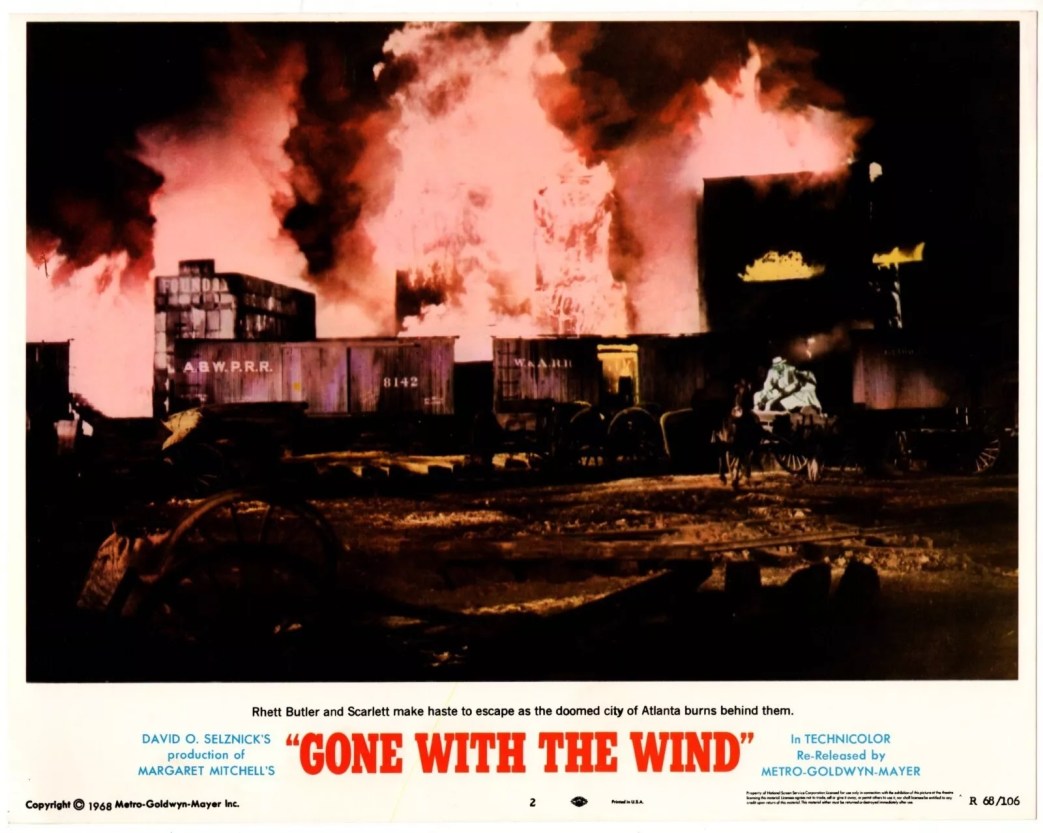

In the film no definite dates are established but there is a lengthy episode in Atlanta during the siege by Sherman’s Army of the Mississippi, which had assaulted Atlanta because it was the most important rail terminal in the Confederacy. The year 1864 was a bitter one for the Union, whose armies had made little progress. Lincoln faced defeat in the presidential contest against McClellan, who represented the “peace” party, dedicated to bringing the war to an end and accepting slavery ipso facto. By August Sherman’s seventy thousand troops had fought through to the Chattahoochee, west of Atlanta. Scarlett O’Hara is in Atlanta as General Johnston’s wounded are being brought in. The city is represented as living in extreme terror, naturally due to the enemy’s artillery and arson.

THE TRUTH

What actually transpired, as related in the memoirs of Sherman as well as those of Gen. Joseph Johnston, the Confederate commander who retreated into Atlanta before Sherman, removes a great deal of the mumbo-jumbo in this episode. After a brilliant flanking operation which fooled Hood, Johnston’s successor, Sherman’s troops marched unopposed into Atlanta on September 1, in a victory that aroused the North and ensured Lincoln’s chances of reelection. Sherman’s first order was dictated by military necessity. Women and children were ordered evacuated because Sherman foresaw that the Confederates might attempt to retake the city. Sherman’s order aroused outraged protests from the Confederates, including General Hood, who wrote Sherman a note full of appeals to God and honor. Sherman’s reply to the Southern general on Sept. 10, 1864, throws light on the supposed “atrocities” of Miss Mitchell’s picture:

“…you yourself burned dwellings along your parapet (in defending Atlanta) and I have seen today fifty houses that you have rendered uninhabitable because they stood in the way of your forts and men. You defended Atlanta on a line so close to town that every cannon shot and many musket shots from our line of investment that overshot their mark went into the habitations of women and children. General Hardee (CSA) did the same at Jonesboro and General Johnston did the same, last summer, at Jackson, Miss…”

In another note to the town council, September 12, Sherman says:

“My orders were not designed to meet the humanities of the case but to prepare for the future struggles in which millions of good people outside Atlanta have a deep interest. We must have peace, not only at Atlanta, but in all America. To secure this we must stop the war that now desolates our once happy and favored country. To stop war we must defeat the rebel armies which are arrayed against the laws and Constitution that all must respect and obey.”

Scarlett flees from Atlanta before the Union occupation, through a wall of burning buildings fired by the Confederates themselves, a fact discreetly omitted from the episode. She goes back to Tara, the plantation outside the city, supposedly in the line of Sherman’s march. What are the facts about Sherman’s march? The general orders for this stunning military blow to the slaveowners contain complete plans of the operation. Before the march began Sherman offered to Governor Brown of Georgia, through intermediaries, a safeguard into Atlanta to discuss a proposal which provided that, in return for disbanding of Georgia’s militia, Sherman’s Army would not molest the countryside as it marched.

Although the Georgia militia had never crossed its own state borders, had in fact been disbanded in September to harvest the corn and sorghum crops, it was mobilized in a desperate resistance. Thereupon Sherman’s engineers destroyed the Atlanta station, roundhouse, and arms factory, and the 62,000 crack troops received orders for the march.

On November 16, the great march to the sea began, on a rich autumn day, with the foraging parties deployed on the wings in a striking combined function of scouting and provisioning the troops, and Sherman looked back at Atlanta as the army sang “John Brown’s Body.” The man whom Liddell Hart has called the “most realistic of idealists” faced the wasp waist of the Confederacy, and the bins of corn and sorghum the Georgia militia had obligingly reaped for him.

Poor white and Negro camp followers were forbidden to accompany the army, although a unit of Negro roadbuilders followed the vanguard.

SHERMAN’S ORDERS

Strictest orders against invading homes or molesting civilians were given; only responsible officers were allowed to destroy property valuable to the Confederacy, such as mills and bridges; and the instructions to the cavalry included a unique clause revealing Sherman’s social conception of the operation:

“…as for horses, mules, wagons, etc., the cavalry may appropriate without limit, discriminating, however, between the rich, who are usually hostile, and the poor or industrious, usually neutral or friendly…” [My italics.]

Sherman’s Army showed no consideration for the Scarlett O’Hara class, but Sherman’s memoirs show the bond between the freed Negroes and the liberating army. Describing his entry into Covington, Sherman says:

“The white people came out of their houses to behold the sight, in spite of their deep hatred of the invaders, and the Negroes were simply frantic with joy. Whenever they heard my name they clustered about my horse, shouted and prayed in their peculiar style, which had a natural eloquence that would have moved a stone.”

Testimony from the Southern press of the period demolishes the dark inferences of Gone With the Wind. The Macon Confederate of Nov. 27, 1864, says, “The only private residences burnt in Milledgeville were those of John Jones, state treasurer, and Mr. Gibbs [a rabid slaveholder]. It is, however, due the Federals to say they respected the families in our city.” The Augusta Chronicle of December 5, “The enemy were under strict discipline and when privates were found depredating private property, they were severely punished by order of General Sherman.” The Savannah Republican of December 21 asked the citizens of the occupied city to “conduct themselves so as to win the admiration of a magnanimous foe.” This does not sound like the horrible marauders of the picture.

On the other hand, the testimony of the secessionist press furnishes interesting counterpoint on the actions of the South’s brave defenders. Confederate deserters in small bands roamed the South and the Charleston Courier of Jan. 10, 1865, declared that the retreating Confederates were “more dreaded” than the Army of Sherman. The Richmond Enquirer, Oct. 6, 1864, said that Confederate Gen. Jubal A. Earley’s “demoralized” army robbed “friend and foe alike.” Earley was the general who raided and burned Chambersburg, Pa., to the ground. There have been no movies about him, or Morgan, who raided Ohio, or the Confederates who slipped in from Canada on St. Albans, New York, and many other New England points.

In the film Scarlett O’Hara uses convict labor in her lumber yard after the war. When Sherman’s Army captured a number of convicts pressed into Confederate Army service, he freed them.

NEGROES AND THE WAR

Gone With the Wind makes the rather curious point that the Negroes were loyal to their masters during the war. Nonetheless the first conscription law of the Confederacy exempted one overseer for every twenty slaves, and in 1864 it was found necessary to exempt one for every fifteen. The main reason why the Georgia militia was kept in the state was to ensure the “docility” of Scarlett O’Hara’s slaves. In January 1864, Jefferson Davis’ own domestic slaves set fire to his official residence in Richmond.

As for atrocities, listen to this on the subject of the eighty thousand Negro troops in the Union Army, from the Richmond Enquirer of Dec. 17, 1863: “Should they be sent to the field, and put in battle, none will be taken prisoners.” (Italics in the original.)

Toward the end of the war, after Sherman had broken the back of the Confederacy, there was a great deal of talk among the slave-owners about conscripting Negro troops, to replace the decimated millions of landless whites who had been engaged in a “poor man’s fight and a rich man’s war.” The Richmond Enquirer, again in 1864, let it be known that the only way to get the slaves to fight for the South was to give them their freedom: “Freedom is [to be] given to the Negro soldier, not because we believe slavery is wrong, but because we must offer to the Negroes inducements to fidelity which he regards as equal, if not greater, than those offered by the enemy.” No Negro ever fired a shot for slavery.

Rhett Butler, the blockade runner of the film, who is engaged in carrying out reactionary England’s aid to the Confederacy, represents the international conspiracy organized by the upper classes of the world whenever one of their fronts is assaulted by the people. Sherman answered him when the Army of the Mississippi had ended up the march by taking Savannah and the British consul was protesting the internment of an English blockade runner. Sherman said to his majesty’s civil servant, “It would afford me great satisfaction to conduct my army to Nassau and wipe out that nest of pirates.”

JAMES DUGAN.

Next week Mr. Dugan will continue his discussion with some facts on Reconstruction misrepresented in “Gone With the Wind.”

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1940/v34n05-jan-23-1940-NM.pdf